Beyond Caste: How Migration Enables Love & Economic Prosperity!

India has achieved significant economic growth, yet conservative practices persist, including strong respect for parental authority, arranged marriage within caste, and ultra-low female employment. As a result, men and women seeking greater freedoms often face severe social repercussions.

Abroad, it’s a different ball game. Only a third of US Hindus say religion is ‘very important’, while 88% support gay marriage. Right across the diaspora, Hindu and Sikh women tend to work, marry their lovers, or leave if relationships prove unsatisfactory.

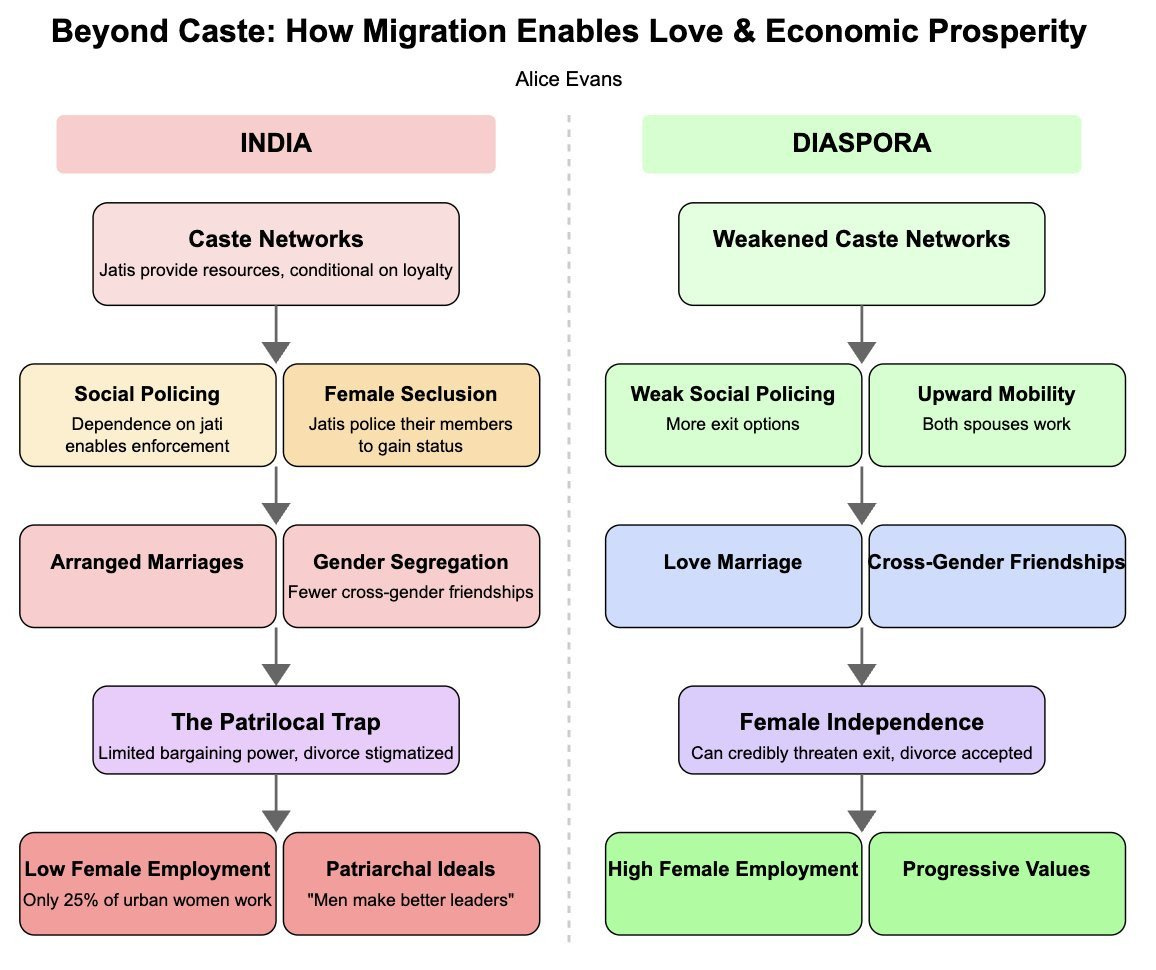

What explains this divergence? Drawing on my global comparative research, Indians tend to depend on their jati (endogamous caste group), which can collectively gain status through female seclusion. This motivates strict policing and arranged marriages. But upon migration, these constraints weaken, fostering greater liberalism, female employment, and gender equality.

Hindu Women Work Abroad but not in India

India’s ultra-low female employment has been the subject of many papers and debates, but hardly anyone talks about the massive differences with the diaspora.

As I advised the World Bank, gender interventions will have the greatest impact if they tackle locally-binding constraints. My role, therefore, is to understand each of these particular drivers of patriarchy - whether that is regards to the dearth of women in German management, Japan’s gender pay gaps, Zambia’s high teenage pregnancies or Latin America’s female homicides. All require careful, in-depth analysis.

Here are the facts. In India, only 25% of urban women work. Rates are highest among Christians and Buddhists, lowest among Muslims and Sikhs.

Overseas, Hindu and Sikh women usually work. This is not just a response to greater economic opportunities. As early as 1979, before Singapore got rich, Indian female economic activity was on par with Chinese and Malays.

Today, 70% of British Indian women work! These rates are especially high among Sikhs and Hindus Over in the US, 89% of Hindus say female employment is a ‘change for the better’. When considering the “honour-income trade-off”, the Hindu and Sikh diaspora evidently prioritises income!

Why is India relatively patriarchal?

Here is my hypothesis. When Muslim rulers conquered India and established their administrations, they idealised female seclusion. Hindu elites likewise adopted purdah to gain patronage and prestige.

India’s caste system then encouraged wider emulation. Higher castes maintained their status through elaborate rules of purity and pollution. This ritual hierarchy created a powerful drive for upward mobility, with entire jatis (endogamous groups) collectively adopting upper-caste practices, including female seclusion. Individuals could not easily resist, as jatis shared (or lost) status collectively and policed their own members. If a family allowed their women to work in the fields or move about unveiled, the caste council could declare them outcaste - severing their marriage networks and social ties.

Caste continues to be important - for jobs, loans and mutual support. Keen to preserve status and social inclusion within this tight-knit group, Indians tend to conform. Moreover, since each jatis gains (or loses) status together, there is strict policing - not just of your own wives and sisters, but other people’s too. Aunties and uncles perennially inquire, “When are you getting married?”.

These patterns persist in the 21st century. Most Indians say it is “very important to stop” both inter-religious and inter-caste marriages - these rates are high among Muslims, Hindus, Jains and Sikhs. Around half of college graduates affirm, inter-caste marriages must be stopped.

Arranged marriages remain widespread, with only 5% of Indians reporting that the bride selected the husband alone. 65% of Indian women say they became acquainted with their husband at or around the time of their wedding. Only 48% of college-educated women actually met their husbands prior to their wedding. Only 21% of adults say they have celebrated ‘Valentine’s Day’.

Castes (and men) continue to maintain honour through female seclusion. When Indians families experience upward economic mobility, they significantly increase restrictions on women’s physical mobility and adopt purdah. The effects are especially strong among Dalits and Other Backward Classes, as well as poor or rural communities, and the least-educated. Female employment remains low - especially across North-Central India.

Even if Indian women want to work, they cannot necessarily realise these preferences. In Mumbai, Jalota and Ho found that slum-dwelling women in Mumbai initially accepted job offers, but then rescinded after speaking to their husbands. I suggest that this is partly a function of the caste system, whereby loyalty is maintained through arranged marriages and divorces is heavily stigmatised. Unable to choose partners based on love OR credibly threaten exit, Indian women struggle to bargain for better terms within marriage. I call this “The Patrilocal Trap”.

On Facebook, Indian men have very few female connections, and across countries this is strongly correlated with low rates of female employment. But without the opportunity to forge friendships, men may not necessarily come to recognise women’s brilliance or relate to them as intellectual equals.

Around half of Indians agree that when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job. Most also agree that men make better political leaders. This holds regardless of religion, Hindus and Muslims are very similar.

Religosity is extremely high across all Indian adults - irrespective of education or rural/urban location, with 61% of college graduates saying they pray daily. A third of college graduate parents say their children receive religious instruction outside the home.

Purity and pollution continue to be idealised, with some villagers practising menstruation taboos. In Chicago, an Indian student shared her experience of working at a micro-finance NGO. When Saanvi was on her period, the rural women told her to sit outside:

“In rural Madhya Pradesh, a menstruating woman is considered impure, like an untouchable… Rural women rarely criticise patriarchy.. They were nice to me, but I doubt they’d want me as a daughter-in-law. They wouldn’t want a woman who goes out and about to the be their daughter in law”.

Two brilliant new films, “The Great Indian Kitchen” and “Mrs”, superbly capture widespread expectations that women should marry, please their in-laws and stay put. Grooms’ family can then extract more labour - expecting her to silently serve, without recognition or reward.

Why is the Hindu and Sikh Diaspora much more Liberal?

Here’s my theory: when Hindus and Sikhs migrate abroad, caste networks tend to break down. They mix, mingle and do business with a far broader range of contacts. No longer beholden to a tight-knit group, policing is far weaker. Communities cannot coerce conformity with threats of ostracism when exit options are great! Social policing weakens.

Manvir (British Sikh shop-owner) articulated precisely this:

“I am Jat, but caste isn’t important in the UK. I source from 50 suppliers - many different castes and religions!” What about inter-caste marriage? “It’s fine. Some elders may object but here many couples marry across caste”.

Manvir’s observations are entirely consistent with Katherine Twamley’s qualitative research: British Hindu and Sikh couples typically choose their partners based on companionship and romantic love!

Even if caste policing breaks down, other elements of Indian culture persist, namely a strong reverence upward mobility.

“Indian parents really plough social mobility, they really push their kids to get ahead. ‘Be an engineer’ - there is an idea that you must aim for social mobility and being the top”.

Hindus really want to be ahead, they aim for the top, to have a nice home, car, schools, etc. And in the West, if both husband and wife work, then you can do much better” - Gaurav and Bilal shared over coffee in Barcelona.

They came from conservative communities in Rajasthan and Bihar, but were both married to women employed in global corporations. Desire for upward mobility coupled with weak caste policing means that Hindu Indian female employment is highly response to economic returns!

Over in US, Hindus actually have the highest rates of full-time employment. Chicago-based Viraj explained that his parents came to the US for medical school, then subsequently rose to achieve seniority at the hospital. He explained, they wanted to achieve social mobility and this required cultural assimilation, “being likeable”.

“All my parents’ friends work, and I think they’re fine with LGBT”.

Female Independence

Baljot was always assertive, even back home in Punjab. One time, she was being sexually harassed by a group of guys, so made a J-turn with her scooter, blocked the road and directly confronted them all. But that was rather unusual, as her wider community was much more patriarchal. Perusing old family documents, she found their family tree, written in Urdu, it only listed male names.

Still today, marriage remains hugely important in consolidating inter-family ties and resources. Hundreds of dowries have been offered for her brother - since he has an engineering degree and a job, making him a beneficial match for other families. But in Toronto, where we became friends, she was always supremely confident and deviant, even cutting her hair short into a bob cut. When one boyfriend ended their long-distance relationship, she remarked:

“I pity him, he will regret, and sure enough he did” (we both cackled).

Baljot rarely goes to the temple and is no haste to marry. Actually, she’s far more concerned about Punjab’s water scarcity and agricultural crisis.

In my interviews with British Hindus and Sikhs, they similarly stressed economic prosperity and liberalism. Chatting at her shop in East London, Jagdeep (45, Sikh, wearing skinny jeans and a pink t-shirt) explained

“When you come to a country, people have to adapt, you can’t think, “what did my parents do back home?… Veiling makes sense in a temple, but when you’re out and about it’s no big deal.” (Translated from Hindi).

Lakshmi (40, Hindu, migrated 20 years ago, now works as an engineer), was similarly open:

Lakshmi: We come, we work, we make friends, and the next generation don’t care about these things, they marry white people.

Alice: Do people ever comment on women’s dressing?

Lakshmi: The other day a woman was wearing a dress with a slit up to her thigh.

Alice And nothing underneath? [Lakshmi affirms]. Well, that’s quite a high bar, the mannequins across the road are all showing their hair.

Lakshmi: Veiling is just for villages, not cities.

We move on to discuss the declining importance of caste. Amit (her husband, a wedding photographer) interjects: And I do lots of inter-caste weddings! No one cares!”. [He proudly shows me his Instagram]

Might Diasporic Women Be More Inclined to Embrace Progressive Values?

In Claudia Goldin’s new paper, she theorises that as economies grow, women are more inclined to embrace progressive values and seize economic opportunities, while men relish traditional status. Might this also be true for the Indian diaspora?

Manvir, a British Sikh shop-owner, suspects this is true, volunteering precisely Goldin’s theory:

“I like my culture, I like my roots. I was on the temple committee in Punjab for 7 years.. Women have more to gain from Western culture as it gives them more freedom, and they argue that it doesn’t make sense not to work”.

How important is religion?

This weekend I visited Southhall, a London suburb home to a large community of Hindus and Sikhs. Perusing local shops, I sought to understand local consumer demand. To quote Jonny Ive (Apple designer),

So what did I find? Well, for starters, delicious channa masala with puri! But I was also struck by absences. On the high street, I couldn’t much evidence of religious instruction. Religious products were primarily sold for wedding rituals and decorations - not daily guidance but special events.

British Sikhs have kindly invited me to their temples - intentionally designed to be inclusive. Everyone enters via the same doors, stows their shoes at the same cloakroom and washes their hands in adjacent basins. Everything is communal. Like others, I borrow a veil from an overflowing box of spares - before we all return to secular life. Luckily, we were just in time for live devotional music and prayers (visually shown in 5 languages). Women sat on one side, men on the other - only separated by a runway carpet. At the Hindu temple, further down the road, there were no veils, no gender segregation, and basins for all. Neither temple provides a faith school, nor do they have any political campaigns. Like the US, it’s pretty low key.

What about low and middle-income countries?

You may object that all this is merely a function of structural transformation, with economic opportunities and social security enabling greater individualism. Doubtless, that’s partly true. But it’s not a full story, as I’ve learned through interviews with Hindus from East Africa and Malaysia.

Between 1834 and 1910, around half a million Indian indentured labourers arrived in Mauritius to work on sugar plantations. Most migrants came from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Southern India, typically from artisan or agricultural backgrounds. High caste groups may have been more hesitant - since crossing the “kala pani” (black water) had long been considered spiritually defiling. Once in Mauritius, jobs were no longer determined by caste; indentured labourers worked under similar conditions.

Building on this levelling, the Arya Samaj movement promoted education, egalitarianism, and priestly roles for all castes. When Mauritius gained independence in 1968, Hindus rallied under a unified ethnic identity.

As caste weakens, families also cease to arrange marriages and they also become more accepting of divorce. Olivia’s family has lived in Mauritius for over 150 years. Working as a pensions officer, she detailed that divorce has become increasingly permissible:

“Sure, caste still exists, but it’s not so major, they’re not doing the backwards stuff… My high-school sweetheart was of Indian descent, and after four years we married, but then after two years, we divorced.

He wanted to live in a flat above his parents, so he could be near them. He’s very close to his parents and his sisters. And they really imposed they really they had very strong very, very strong ties to him, and he didn't ever say no. He he totally prioritised the family. What I wanted was secondary.

Also, he didn’t do much of the care work; his mother had doted on him. and what she wanted was secondary. She also says that he didn't do the much of the care work, so he sort of expected he said he said that his mother doted on him. She would do everything for him and treated him so well and, you know, “I want this for my son”. “I want this my son”. Like, reserving food for him… He wanted me be a second mother”

When I divorced him, my family welcomed me back. I lived with my family for ten years, and they prioritised my happiness”.

That was also the vibe in South East Asia. As early as 1976, ethnographic research suggested that caste was weakening in Melaka - with declining concern for occupational sorting and inter-marriage. At that time, Indian female economic activity was already on par with Chinese and Malays. Today, if you talk to taxi drivers or industry titans, no one expresses much interest in caste. Out at parties, your Hindu single friends might not even be asked whether they are married. Uncles and aunties are typically far more interested in business!

Unlocking Caste Constraints

Love and work are usually treated as separate, but I suggest they are deeply intertwined through India’s caste system.

Arranged marriages remain common in India because they consolidate inclusion in caste-networks, which provide jobs, loans and mutual support. Since jatis collectively gain status through both solidarity and female seclusion, they tend to punish inter-caste marriage and female freedoms. Concerned to avoid ruinous ostracism, families impose tight restrictions, keeping their sons and daughters under close surveillance.

Patriarchy is then amplified: male honour depends on female seclusion, limiting cross-gender friendships, understanding and empathy. Gender segregation also make it much harder to marry for love - to find a man who actually values her wants and welfare. Threats of divorce are hardly credibly, since it is so heavily stigmatised. The groom’s family can then enforce their preferences - whether that is for her to stay at home or endure , even exercising impunity for violence.

However, when Hindus and Sikhs move abroad, caste breaks down and social policing weakens. Men and women can then forge friendships, choose caring partners, pursue economic opportunities, demonstrate their prowess, and even run for President!

Film recommendation!

“Defiance: Fighting the Far-Right” brilliantly highlights how 1970s British South Asians were assimilating into Western youth culture (dressing like any other teen, sporting afros), but were nevertheless harassed and violently attacked by racist bullies. In response to murders, Asians united to protect their community.

Interesting survey. But is there any Is there any data on how diverse the Indian diaspora is? Are there actually a considerable number of people from lower castes? It's easy for upper-caste individuals to claim they don't believe in caste, but is that what they actually practice?

I'm not sure how to find this data, but based on my strong feeling and personal experience, India is not creating enough opportunities for people from lower castes to become economically capable of going abroad.

Example from personal experience:

I’ve worked in Copenhagen and the UK for Indian companies. In both places, on my floor—which typically comprised about 100 people—I couldn’t find a single person from a lower caste background. The upper-caste colleagues were often quite casteist. They would try to identify someone's caste based on their surname or eating habits and treat them accordingly. In both the UK and Copenhagen, all the senior managers were upper caste, and some asked me about my caste as early as the second conversation—essentially during introductions.

I believe, once people from lower castes do manage to go abroad, it becomes comparatively easier (than in India) to break caste barriers.

But are we creating enough opportunities within India?

Religions/religious systems provide necessary comforts to adherents. What is often missed is that these systems provide differing comforts to males than they do to females. And that these comforts prioritize male needs.

To females, religion provides, at its most essential level, something close to solace. And to males, it provides a "place" within a male-dominated, and desired, hierarchy. Anything beyond those two differing comforts is proved extraneous in all diasporas.

As a person moves further away from a religious epicenter, each person—male and female— takes what provides the most comfort and begins discarding other part of that ideology. Misogyny and caste are *both* borne of a male desire to have everything ranked within their preferred hierarchy. Women do not dare, for example, to aspire to be the Roman Catholic pope. They are left with a bit of solace for their all-around low status within that system.

Females are left to take whatever comfort and consolation they can from all these ideologies. In return, females perform almost all the sustaining tasks of those religions. Because without these services, females are not even allowed a bit of solace.

When females are no longer satisfied with mere consolation for a misogynistic, male-centered system, the religious system/culture will weaken and fail.

Although the behavior of the diaspora of any ideology is interesting, it is even more important to see what remains in the diaspora. Although marginally better for most females, the diaspora of all religions reveal the truth of religions: they serve to provide males what they want and need and females are left with occasional scraps of comfort for which many hours of service are required. This is true in Western and Eastern ideologies.

Religions are the patriarchy's greatest deceptive cons. Slowly and unevenly, this is being revealed to females. Even those who cannot admit it out loud, or to strangers, pollsters, their own families. But more of us have seen through the patriarchal veil. We are just silent most of the time. We sacrifice the promised "solace" and we see just what religion has really done to us.