Why do Poor Indian Women Reject Office Jobs?

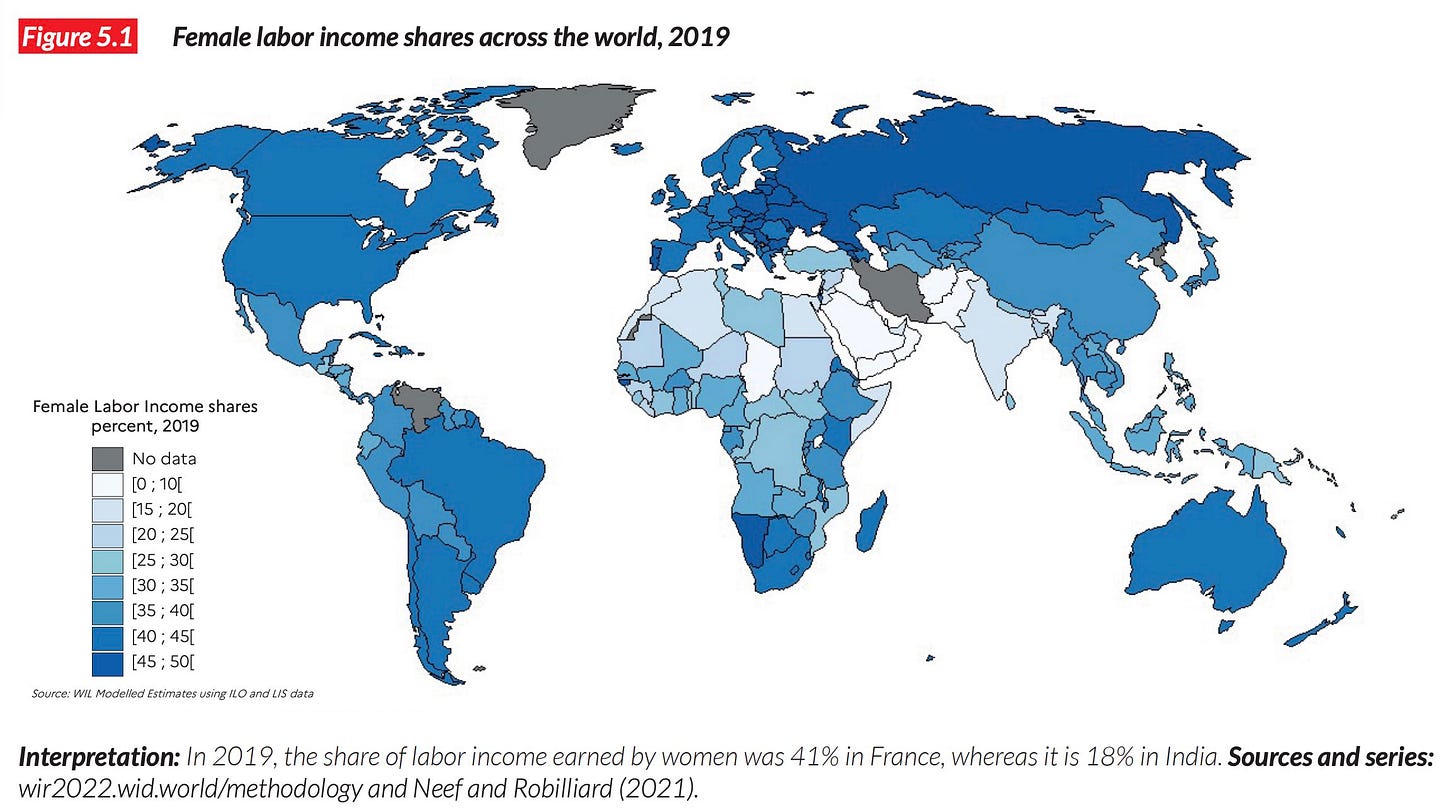

India’s female labour force participation is ultra low.

I have previously theorised this as an “Honour-Income Trade-Off”. Men are expected to provide as breadwinners, while women are supposed to stay away from unrelated men. Female labour supply only rises when available earnings are high enough to compensate for cultural preferences.

Moreover, since cooperation is secured through inter-marriage (while divorce is stigmatised), girls are socialised to please their husbands and stay put. Husbands then have heightened authority. I call this “The Patrilocal Trap”.

Suhani Jalota’s Job Market Paper (co-authored with Lisa Ho) examines all this empirically. It is one of the most innovative and insightful papers I have ever seen on how female employment is suppressed by culture. Certainly my favourite JMP of 2023.

To understand barriers to employment in Mumbai, Jalota and Ho implement a Randomised Control Trial, with 3,200 housewives and 860 husbands from a slum resettlement community. They compared women’s take-up of jobs at home and nearby offices.

Work tasks were identical: labelling data for artificial intelligence models. The offices were women-only, with female supervisors, five minutes walk from respondents homes, and permitted children. Housewives were offered piece-rate work, for 60 days, with flexibility in work hours and load. Everything was maximised to make these jobs female-friendly.

Housewives were randomly offered either Work-from-Home or Work-from-Office jobs. Wages were also randomised: $60, $150 and $300. The highest wage exceeds the average monthly household income of $250. Husbands from the same households were also surveyed.

Did poor Indian women seize the female-friendly office jobs?

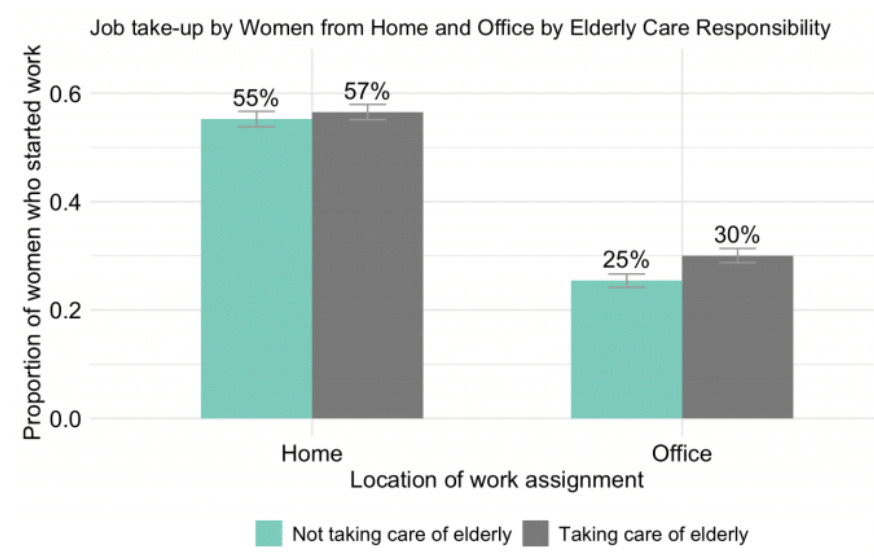

Only 27% of their sample took up the office jobs. Whereas 56% wanted the home-based work. Women doubly preferred to work from home.

Women were more likely to take up the office jobs when pay increased from $60 to $150, but were totally insensitive to offers of $300.

Only half of the female workers remained employed for the full two months.

450 (already employed) husbands were given the exact same offers. Unlike their wives, men were more responsive to higher salaries, and had no preference for home-work.

Why did most women reject office jobs?

Care constraints?

Actually, women with young children were no more likely to accept office jobs.

Women with elderly care responsibilities were actually more likely to accept office jobs.

Maybe housewives valued home-based multi-tasking?

Jalota and Ho tested for this too! They introduced home-based work that had to be completed within a set time period, prohibiting multi-tasking. Even with these restrictions, women still preferred to work from home.

Husbands said “no”

Jalota and Ho’s track women’s workforce participation over time. 63% of women accept the job on Day 1, but only 41% commenced work.

What made them backtrack?

Women discussed the job offers with their husbands. Women from less progressive households were most likely to backtrack and decline work.

42% of the housewives said they were rejecting employment due to their husbands’ disapproval. Only 28% said they were allowed to work outside the home. Just 18% said they had permission work outside their local community.

Men’s resistance may partly reflect anticipation of social disapproval. Only 32% of husbands believed that at least half the men in their community would think it’s right for women to work outside the home.

“My husband said I could only work over his dead body. As long as he is alive, I have no reason to work outside [home]” - surveyed housewife

Suhani Jalota & Lisa Ho’s paper is PHENOMENALLY BRILLIANT!

Indians generally believe that men should be breadwinners and women should stay away from unrelated men. These beliefs and anticipation of condemnation suppress female employment outside the home - even if offices are safe, nearby and female-friendly. Rejection of office jobs cannot be explained by low wages or housework.

Suhani Jalota and Lisa Ho (job market candidates at Stanford and MIT) show all this empirically. It is the most innovative and insightful paper I’ve ever seen on how female employment is suppressed by culture.

Their brilliant longitudinal analysis also enables them to shed light on another aspect of this patriarchal puzzle. 68% of women in their sample accept work then backtrack after discussing with their husbands.

Why is this? Why are men are more able to assert their preferences?

I suggest that they are caught in “The Patrilocal Trap”. Indians remain heavily reliant on caste-based social cooperation, which is consolidated through intermarriage with strict prohibitions on divorce. Girls are socialised to marry, please their in-laws and stay put. Divorce marks total humiliating failure; she is blamed.

In rural Karnataka, Francis Bloch and Vijayendra Rao found that grooms may beat their new brides in order to coercively extract large dowries. Husbands are so confident in their wife’s loyalty that they beat them into begging their parents for more money.

Indian husbands can thus assert their preferences - whether it is for larger dowries or strict seclusion.

Truly, this is my favourite job market paper of 2023. It elucidates several causal mechanisms suppressing female employment in India, namely husbands’ resistance, husbands’ anticipation of stigma and also husbands’ heightened authority.

BRAVO to Suhani Jalhota and Lisa Ho!