The Patrilocal Trap

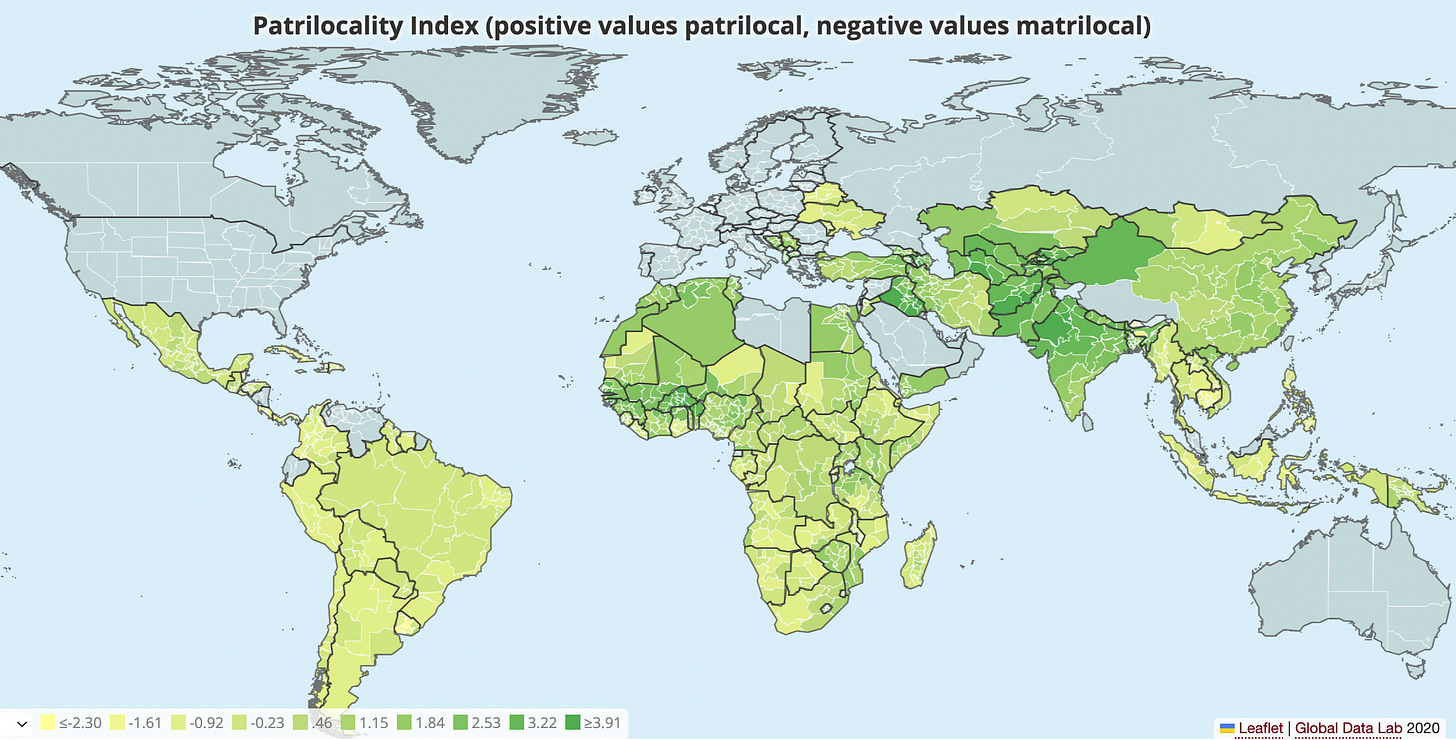

Pre-Christian Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, Central Asia and East Asia were all patrilineal and patrilocal. Sons were scions of the family line, inherited land/ herds, and remained with their clan. Households strengthened trusted networks through inter-marriage. Daughters were socialised to marry, please their in-laws and stay put. Marriages were arranged; divorce was stigmatised. Wives’ inability to credibly threaten exit gave their husband’s family the upper hand. Mothers-in-law could enforce their preferences - to exploit labour or restrict mobility. I call this “The Patrilocal Trap”.

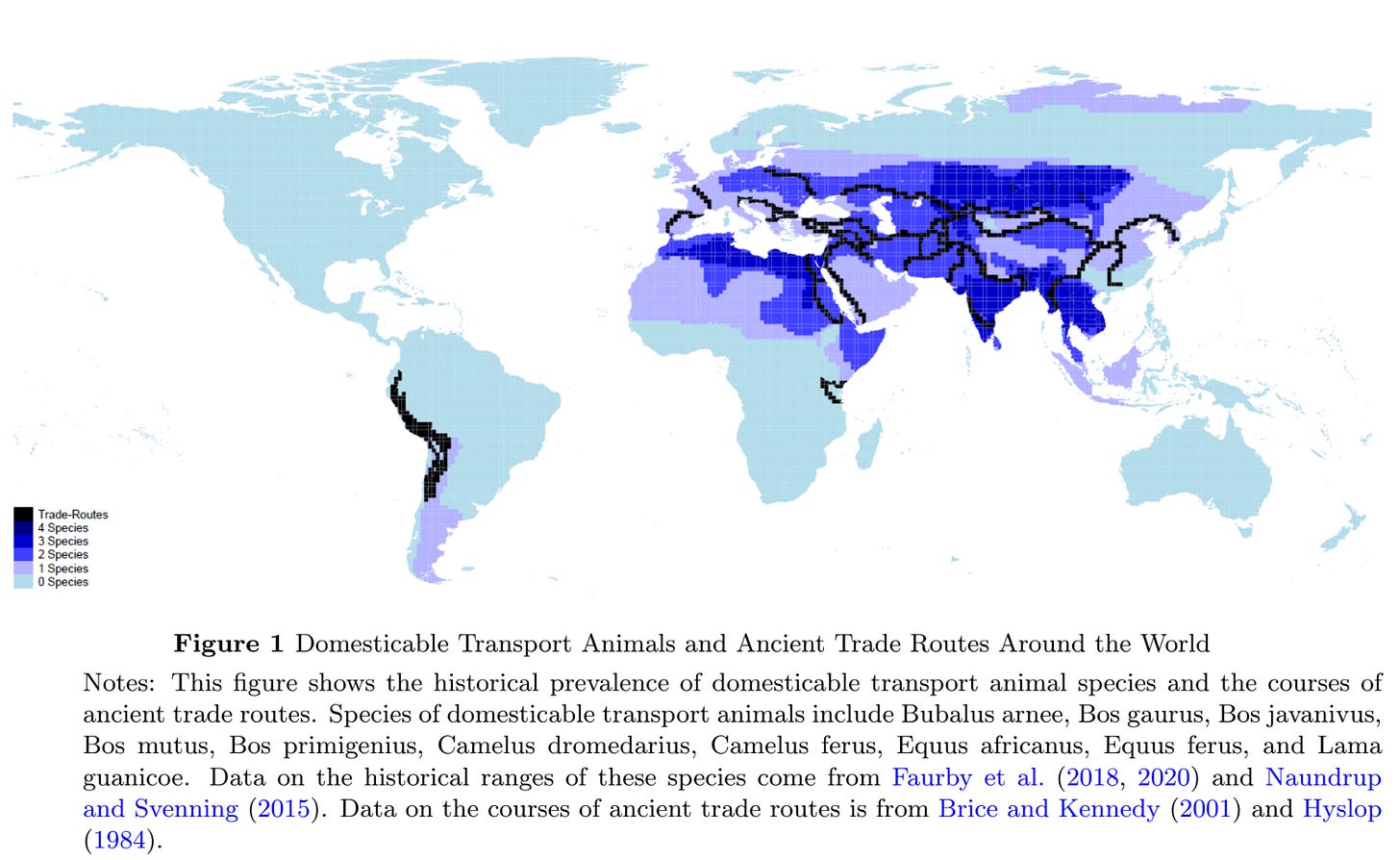

What explains the global-historical variation in patrilocality? Through my globally comparative historical analysis, I realise that arranged patrilocal marriages with stigmatised divorce were common in regions with inherited wealth, beasts of burden and long-distance trade. What might explain this correlation?

It is impossible to know why people did stuff a thousand years ago. But let me suggest a hypothesis for arranged patrilocal marriages, with stigmatised divorce:

Animals were domesticated, accumulated and traded as herds. Cattle, the plow and irrigation raised crop yields. Across Eurasia, cereals could be traded and stored.

Wealth turned patrilineal inheritance into a key element of social organisation. Where land or herds were valuable, family wealth was threatened by raiders. Alliances became imperative.

Long-distance trade was enabled by beasts of burden. This likely encouraged large-scale networks of trust and cooperation (beyond immediate kin).

Wider alliances were established through inter-marriages. Patrilocal lineages defended valuable herds and land, while extended networks jointly organised irrigation, infrastructure, insurance, healthcare, and investment.

How did Europe escape the Patrilocal Trap?

In Western Europe, patrilocality was crushed by the Church. From 300-1300 CE, the Roman Catholic Church and Carolingian Empire stamped out cousin marriage and polygamy. English peasants disregarded lineage and rarely exchanged work with extended kin. Young men and women often worked in service until they saved enough to establish nuclear households. Precociously deep wage labour markets and urbanisation accelerated exogamy.

However, Anglicans and Catholic Churches still proscribed divorce. The French Revolution gave couples the right to divorce in 1792, but by 1816 this was abolished. Europeans’ exit options remained extremely weak until the late 1900s.

In Catholic Ireland, the right to divorce was only introduced in 1996. Female labour force participation subsequently increased. Since marriage no longer provided reliable insurance, Irish women increasingly sought economic independence. This generates a positive feedback loop. As more women exit, separation is normalised.

Medieval marriage consolidated alliances

Royal dynasties arranged marriages to cement alliances. Amir Timur, for example, married Tukal-Khanum (a daughter of the Mongol Khan Khrizr Khoja). Similarly in Europe, royal inter-marriages fostered peace. King Henry VIII married Catherine of Aragon to maintain the political alliance between England and Spain.

In India, social cooperation has long been organised through caste networks. Upper caste populations in North India became much more endogamous around 1600 years ago, estimate Basu et al. The powerful Gupta Empire enforced moral strictures, under the age of Vedic Brahminism. Endogamy could have only been maintained through arranged marriages, with prohibitions on divorce.

In her wonderful book on Medieval Rajasthan, Sabita Singh details that daughters were given in marriage to strengthen kinship ties, secure peace or even hoodwink the enemy. Mughal Emperor Akbar made 40 political marriages for himself, his sons and his eldest grandson - almost all with major Rajput chiefs. Rajput rulers often considered marriage alliances with Mughals as “an unavoidable but essentially degrading necessity”.

All castes in Medieval Rajasthan favoured early, arranged marriages. Peasant daughters were often married before 16. Breaking off engagements was considered humiliating, a terrible offence. This was enforced by the state - which fined or forbid cancellation of engagements.

Precarity, caste and divorce stigma

21st century Indians remain heavily dependent on their jati.

When Indians need help, support, access to raw materials, markets, loans, or jobs, they usually turn to their trusted caste network. Insiders derive great benefit from jati and strengthen trust through wedlock. Assemblies of older men maintain jati endogamy with punishments of ostracism. An entire family might be expelled from the village because of one daughter's misdeeds.

Urbanisation has not undone caste. Residential segregation by caste and religion is very high - en par with racial segregation in the US.

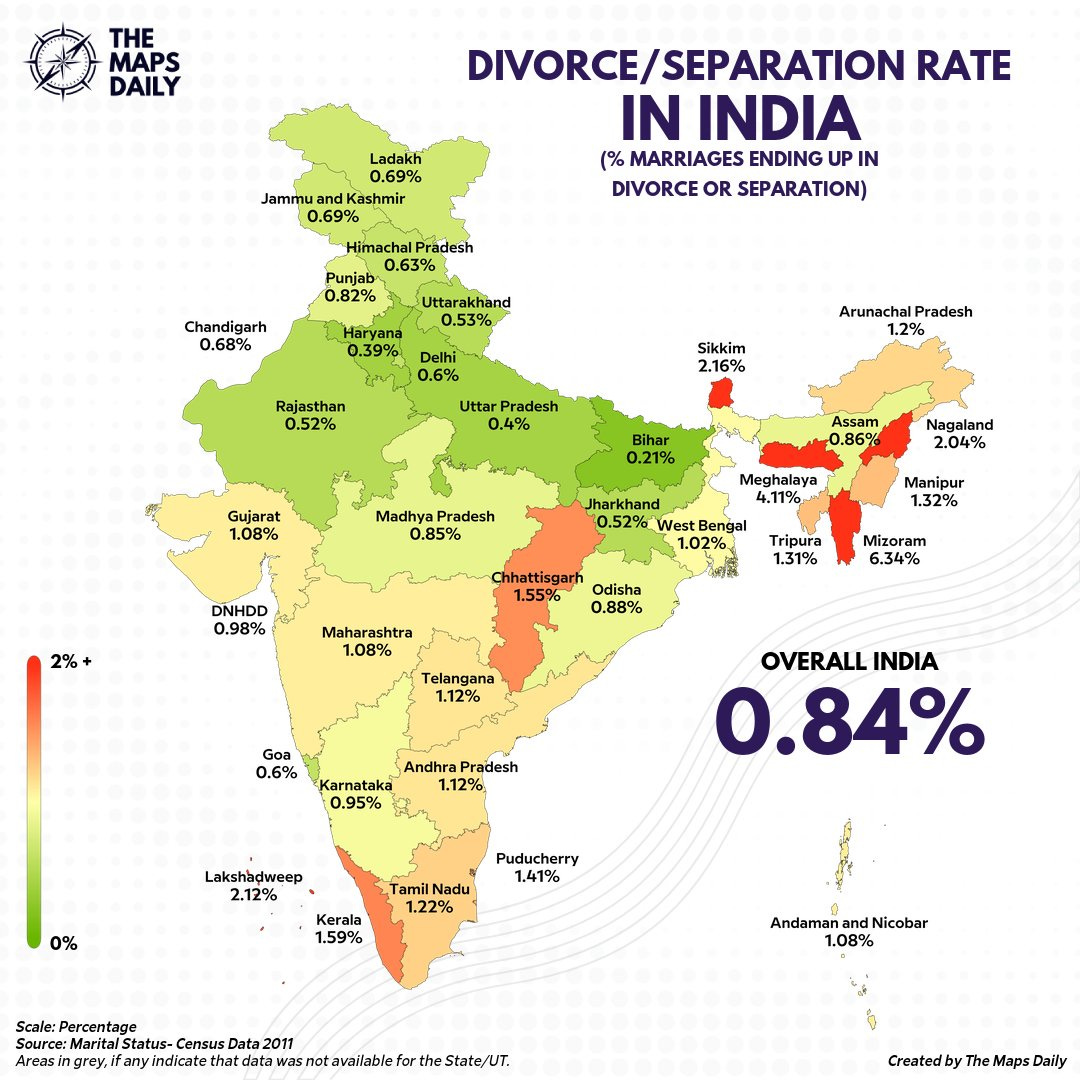

Caste endogamy is maintained by arranged marriages and divorce stigma. Divorce remain ultra low nationwide, except in the Christian and Buddhist Northeast.

Indian women are thus caught in “The Patrilocal Trap”. Girls are socialised to please their in-laws. Single women face pervasive hostility, they face major pressures to marry. But exit is almost unthinkable.

In rural Karnataka, Francis Bloch and Vijayendra Rao found that grooms may beat their new brides in order to coercively extract large dowries. Husbands are so confident in their wife’s loyalty that they beat them into begging their parents for more money.

The Patrilocal Trap

Across Eurasia, patrilocal clans secured wider cooperation through arranged marriage. Girls were socialised to please their in-laws and stay put. Her inability to credibly threaten exit gave in-laws the upper hand.

Western Europe escaped patrilocality thanks to a draconian Catholic Church. But divorce remained prohibited. It was only with sexual liberation and job-creating economic growth in the late 20th century that wives could actually leave.

In low/middle-income patrilocal societies (like India), close-knit kinship is paramount and divorce is stigmatised. While paid work enhances a wife’s spending power, she cannot credibly threaten to exit. She is caught in what I call “The Patrilocal Trap”.

Actually I live in United States as an American we have not escaped this we have patriarchy.Also, for patriarchy, it's normalized for a woman to leave her family's house to go live with that man, even in the Bible. And people don't question, why does the woman have to leave her hometown, her family, to go live with that man? Well, if you think of it, who's the man living with? He lives with his parents, or he lives alone in his hometown where he's near his family. And what no one ever thinks about is it should not be normal for a woman to leave her hometown and her family. Why? Because if you leave your family, you have no support system. When I had an ex, I lived with his mother-in-law, and I was severely mistreated by all of his relatives and family, and I was treated like trash. And then I left. And what I noticed is that they treated their other daughter-in-law, who was his brother's wife, much better than me, but that's not the point. The point is that you're all isolated, and you're at the mercy of other people when you leave your family. You have no support system. I don't have any siblings, but if I had any, they could have helped me. My mom could have been like, oh, you're being mistreated. You can live with me. You could have people stand up for you. If you have friends in the hometown you're from, they could be like, hey, don't treat her like that. So when a woman leaves, she's actually isolated, and it's a way for patriarchy to allow abuse to be able to occur, because she's an outsider. No one cares about her, and she's at the mercy of whoever she's near, and the kindness and whatever of that man..These people love that man and know him you are a outsider a stranger never truly family or friends hence the whole crazy mother in law or crazy sister in law trope it's them against you and worse he listens to mom over you hence mommy's boy arc. When I was injured in a car accident with ex his friends rushed to comfort him no one ever checked on me i felt so isolated back then. Whenever we argued it was a replaceable woman being mean to someone elses child even though he was an adult his mom babied him and worse even showed him other women to replace me who she was closer too. You can't make friends with his buddies even if they are female as they have 100% loyalty to him as they grew up together I remember trying to befriend his friends they were nice to me in public behind my back with him talked shit about me cause they were loyal to him not me. His family viewed me as the woman he slept with a role easily replaceable ring or not. His friends that were male even tried to take him to strip clubs and encourage him to cheat I met other women patriarchy comes in different forms but leaving your hometown to live with a man is the worst thing you can do especially living in his moms home or even if you live together in a place he has it's always his home his rules if in his family home their house their rules and whatever he decides you get zero control and on top of that invisible labor for him if you live with his family it's worse you have chores for them and him.

Great piece thank you. As I'm sure you're aware, Joseph Henrich in "The WEIRDest People in the World" touches on similar themes of family structure, the Church's crushing of cousin marriage, etc. New subscriber, am going over your previous articles now, thank you very much, looking forward to your book.