Why are Gender Pay Gaps so Large in Japan and South Korea?

All East Asian tigers have converged economically with rich industrialised democracies, but only some have converged culturally, in terms of gender equality.

Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan are closing gender gaps in pay, seniority and parliamentary representation. Japan and South Korea, meanwhile, have the largest gender pay gaps in the OECD. Management remains 85% male. Female graduates are treated like secretaries, expected to pour the tea and run errands.

In Europe, women are penalised by motherhood, but in Japan and Korea, motherhood is simply irrelevant: they are penalised whether they are mothers, or not. In Japan, a female graduate earns the same as a man who has only completed school.

Japanese businesses have lobbied again legislative change, even refusing sexual harassment training. Courts routinely deny systematic discrimination. Employers cannot even be sued for sexual harassment. Employees can only ask the Ministry of Labour for mediation. Accusations of abuse are mostly ignored.

Many hypotheses have been offered for Japan and South Korea’s gender pay gaps:

Firms demand long hours, so discriminate against mothers

Large firms train workers in-house, so never ran out of skilled labour

Spousal benefits (tax and health care) in Japan create perverse incentives.

All are unconvincing.

In 1900, East Asian women were generally unfree and oppressed, yet Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong have since become much more gender equal (achieving near parity in pay, seniority, and political representation)

Singaporean and Chinese women work much longer hours. Moreover, South Korea’s gender pay gap is unrelated to motherhood.

All East Asian economies have experienced low unemployment. Japanese firms complain of labour shortages. Japanese and Korean firms are no longer especially large.

Korea’s gender pay gap is larger than Japan’s, but it has no policy of spousal benefits.

What explains this discrepancy?

Japan and South Korea’s jobs for life

Lifetime employment is the major, structural difference between East Asia’s tigers. During Japan’s economic miracle, company managers soothed labour unrest by rewarding both white collar and blue collar workers with career paths and job protection. This same system was adopted in Korea.

Given soaring productivity and double digit growth, large firms were confident in continued labour demand. Workers were hired, trained, then stayed till retirement. To maximise output, employees are expected to work extremely long hours, while also accepting re-assignment to new locations.

Commitment is rewarded by seniority pay - for years of service rather than productivity. Quid pro quo: work hard and you’ll be rewarded later. The wage premium for continued work in the same company is highest in Korea and Japan.

As one immigrant observes,

"The salaryman/employer relationship is best characterized as “You swear yourself to us, body and soul, and in return we will isolate you from all risks”’.

Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan (SHKT) never developed this system of lifetime employment. Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) - the main employers - could not afford long-term promises. Singapore has a flexi-wage system: most workers are paid a basic monthly wage and a variable performance bonus.

Sexist firms keep women subordinate

Initially, some Japanese firms prohibited women from taking their entrance exams. From the mid-1980s, they experienced labour shortages, so increasingly incorporated women - but only as menial underlings.

Companies created distinct career paths. Men are on the career track (sōgōshoku); women are assigned the ‘dead-end clerical track’ (ippan shoku in Japanese). Destined to servitude, women are largely denied positions of responsibility. Personnel officers openly say that women are uncommitted or incapable.

Korea and Japan’s gender pay gaps are not caused by lack of skills, child care or under-development, it is sexism.

Male school leavers are much more likely to become managers than female graduates.

Disrespect and discrimination loom large. Japanese and Korean women often feel pressured to quit upon marriage. Maternity harassment is so widespread, there’s even a Japanese word for it: ‘matahara’. Korean and Japanese wives typically become non-regular workers, where their earnings are 40% lower and lack benefits (like company pensions).

Most Korean and Japanese men, meanwhile, remain in regular work - on higher wages, with job security, and full benefits.

Economically, Japan and South Korea have now converged with rich industrialised countries. But culturally, there is a huge difference. Management is monopolised by men.

Low status men are made superior

Gender income disparities are largest among low ranking and less educated workers. This fact has been totally overlooked, but it sheds light on our puzzle. Men at the bottom of the pyramid are treated like workhorses; they lack high pay, status and seniority. Company loyalty is rewarded with patriarchy. In Shintani Metals, blue-collar men are given positions of authority, then use rough language to bully junior women. This is nothing to do with work hours or pregnancy: it is patriarchy.

Low-status men are elevated above women.

To summarise, Japan and South Korea have enshrined a system of lifetime employment and seniority pay for both blue collar and white collar workers. Firms are extremely sexist: men are treated as future managers, women are their subordinates. These inequalities are largest amongst low status regular workers. Fed up and frustrated, wives quit regular work to spend more time with their children and undertake non-regular, low paid work.

But why are South Korean and Japanese firms so sexist?

Lifetime employment requires commitment from low-ranking men

Lifetime employment generates a unique tension: employers want to heavily invest in workers’ skills, maximise working hours, while deterring exit. Seniority pay incentivises workers to stay, but promises of increments in twenty years time provide little solace to workers who are already exhausted.

Companies initially tried to rally employees by heralding them as ‘corporate warriors’ (kigyô senshi), ‘selfless devotion’, (messhi hôkô), ‘advance guard’ (senpei). But over the 1980s, many became disillusioned. New terms entered public discussions:

‘Death from overwork’ (karôshi)

‘Reluctance to go home’ (kitaku-kyohi)

‘Workers forced to live away from their families, due to job transfers (tanshin funin)

‘Window-sill tribe’ (madogiwa-zoku) referred to men who had been promoted to pointless jobs, and now simply stared to the scenery.

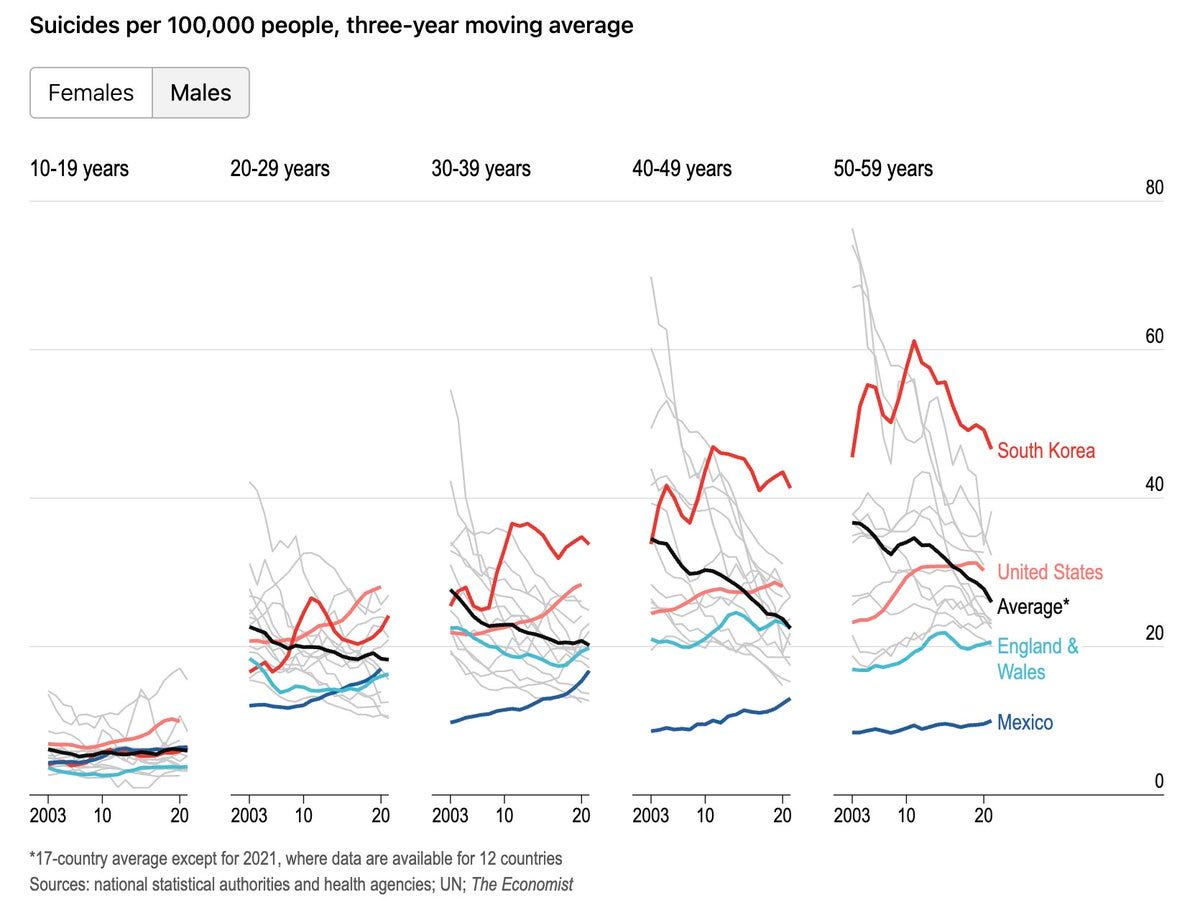

Headlines featured stories of men dying from exhaustion. Japan and South Korea have extraordinarily high rates of male suicide.

Male discontent generates a profound problem for corporations modelled on lifetime commitment, heavy investment and seniority pay. While shorter work hours would help, this has not occurred. East Asian firms have sought to maintain global competitiveness through ultra long hours.

Now you see how this all fits together. South Korean and Japanese corporations have placated disgruntled men by entrenching patriarchy. If women were treated as equals that would be polluting, it would undermine men’s self respect and work commitment. Why give your life to a company that treats you like a mere woman?

Company men’s egos continue to be pampered after hours. Japanese firms allocated 5% of their operating budgets to nights out with charming hostesses. Masculine pleasure is corporate strategy.

Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan’s firms elevated women and recognised their competence

Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan (‘SHKT’) never had these systems of seniority pay. Workers were simply rewarded with basic wages and productivity bonuses. SMEs didn’t heavily invest in their workers nor expect lifetime commitment. Firms did not need to secure unwavering loyalty. This systematic difference mediated their incorporation of women.

In the 1960s and 1970s, gender divisions of labour were broadly similar across East Asia. Women predominated in low paid work and exited upon marriage. Motherhood was central to their identities. By the 1980s, demand for skilled male labour was outpacing supply. Given high female education, low fertility and sky-high productivity, it became profitable to recruit and retain women. While SHKT firms were indubitably sexist, they didn’t face the same challenge of placating low-status men.

Lucrative job opportunities raised girls’ aspirations and status. By 1995, women comprised 50% of Taiwanese undergraduates – just like Britain. This sharply contrasts with Japan and South Korea’s much larger gender disparities. SHKT women overwhelmingly work full-time and make it to management. By 2002, 26% of Hong Kong managers were women. Even if their husbands become richer, Taiwanese women remain employed. Women want to work because they are valued. Singapore’s adjusted gender pay gap is just 6%. As one young Singaporean woman commented about Japanese managers treating female graduates like secretaries,

“My mother was asked to pour the tea once, early in her career. But that was a long time ago, LOL!”.

Eager to engage fathers, the Government of Singapore runs a month-long campaign called “DADS for Life”.

The rise of respected, networked and wealthy women has increased their electoral competitiveness. Gender quotas were adopted in Taiwan after feminist lobbying. Women now comprise 42% of legislators. Once in power, Taiwanese women sponsor more bills and favour women’s interests. President Tsai Ing-wen was not only re-elected in 2020, but has also achieved a high approval rating (73%). She is the only female Asian head of state who is not from a political dynasty. Over in Singapore, the People’s Action Party introduced a quota to appeal to women voters. Since the 1990s, feminist coalitions have successfully overturned discriminatory laws. Attitudes are rapidly converging with Europe and North America.

South Korea and Japan have raised patriarchal expectations and now grapple with the consequences

Non-elite men now struggle to secure status, social mobility and female servitude. Real wages have stagnated in Japan. Almost 30% of 50 year old Japanese men have never married. Thanks to historic sex ratios, Korean men face a skewed dating market. Low-ranking men really struggle to get girlfriends. Jilted guys jizz into women’s handbags, venting rage with ‘semen terrorism’. Frustrated Korean incels seethe with self-righteous indignation, vilifying women on 4Chan, and electing an anti-feminist president.

Throughout global history, sexists have aggressively resisted female pollution

Male prestige has been preserved by banning women.

As one English unionist despaired in the early 1800s, “It was a crying evil to see women getting into the trade”. When Kidderminster women were put to work on new looms, all the male weavers went on strike, won within the week and maintained their monopoly of the trade. Working-class men also lobbied for restrictive labour legislation (such as the 1842 Mines Act). Only after labour shortages did firms eventually remove marriage bars.

Let’s not forget my former home, the University of Cambridge. When Senate House voted against women receiving degrees in 1921, male undergraduates triumphantly marched to Newnham College, grabbed a coal trolley and used it like ‘a battering-ram to smash down Clough Gate’.

Early 20th century Russian men were also extremely prejudiced; unions relegated women to unskilled inferiors. But given high productivity targets and a massive shortage of workers (especially post WW2), Soviet firms reluctantly hired women. Like Japan, blue collar men often earned more than female graduates. But Russian women pressed ahead and persevered. Today, women comprise over forty percent of Russia’s published economists and business managers.

Industrialising communists and capitalists, the world over, have ultimately hired and promoted skilled women. South Korea and Japan buck the trend. Eager for the loyal commitment of low-ranking, exhausted and disgruntled men, companies have paid with patriarchy.

Great analysis as usual. You may be interested in a light-hearted but serious examination of many of these issues in Japan through the "Full-time Wife Escapist" drama (https://www.netflix.com/title/81410833). It is a refreshingly frank examination of many of the constraints and expectations placed on women. If culture is a leading indicator of change, there may be hope yet.

As a Japanese man, I couldn't agree with the content of the article. It seems that the author is discussing the year 2023 using relatively old literature from the 1990s and beyond.

It is true that there is a gender pay gap in Japan, and it is also true that it is always women who abandon their careers when they have children, and that many of them end up working part-time.

However, I don't think this is the result of discrimination against women by companies, or due to patriarchal values.

It was only 30 years ago that there was gender discrimination in the workplace (not only discrimination against women, but men were also not allowed to become nurses, cabin attendants or kindergarten teachers). Since then, there has been no difference in basic pay for men and women employed in the same job. Even 20 years ago, a human resources manager who said that women were not capable would have been immediately removed from the office. I was unable to find any information on the internet about a company called “Shintani Metals” that bullies women. Is there any data to suggest that oppressing women satisfies the self-esteem of low-income men? In Japan in 2025, a law was passed to prevent women from going bankrupt in the Handsome Men's Club (this does not apply to bankruptcies among men).

I think the main reasons why the gender pay gap is not being closed are that childcare leave is a career break for both men and women, and that women tend to want to marry men who earn more than they do (there is data to support this).

In Japan, it is possible to take two years of paid childcare leave while still working, and this is also available to men. However, in many cases, this period of leave is not considered to be part of one's work history, and this is a disadvantage in Japanese companies where the length of one's work history is strongly correlated with pay and promotions. There is a marked tendency among Japanese women to want to marry men who earn more than they do (perhaps this is a patriarchal value held by women), and in many cases the man's wages are higher than the woman's. In such cases, it is financially rational for the woman to take childcare leave and interrupt her career.

It is difficult to change women's values immediately, but I think that childcare experience can also be put to use in work, so I hope that companies will start to count childcare leave as part of a person's work history.