Can Architecture Reveal the Spread of Purdah?

When conquerors seized new territories, they didn’t just extract surplus - they also crafted new administrations and alliances, new pathways to patronage and prestige. Aspiring locals often adopted their customs to gain wealth and status.

But how can we trace cultural evolution when written records are scarce? Architecture offers a revealing window. Buildings aren’t just bricks and mortar - they’re beacons of cultural evolution!

In societies where male honour depended on female seclusion, this was preserved through design. Today, I explore how architecture reveals the spread of purdah (female seclusion). Across North India, the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Emperors built palaces with extensive women’s quarters (zenanas). Hindu nobles likewise added screened galleries and walled courtyards. Emulation secured patronage and prestige.

The caste system provided a powerful vehicle for transmitting upper-caste customs nationwide, as entire jatis copied upper castes to gain status and social inclusion.

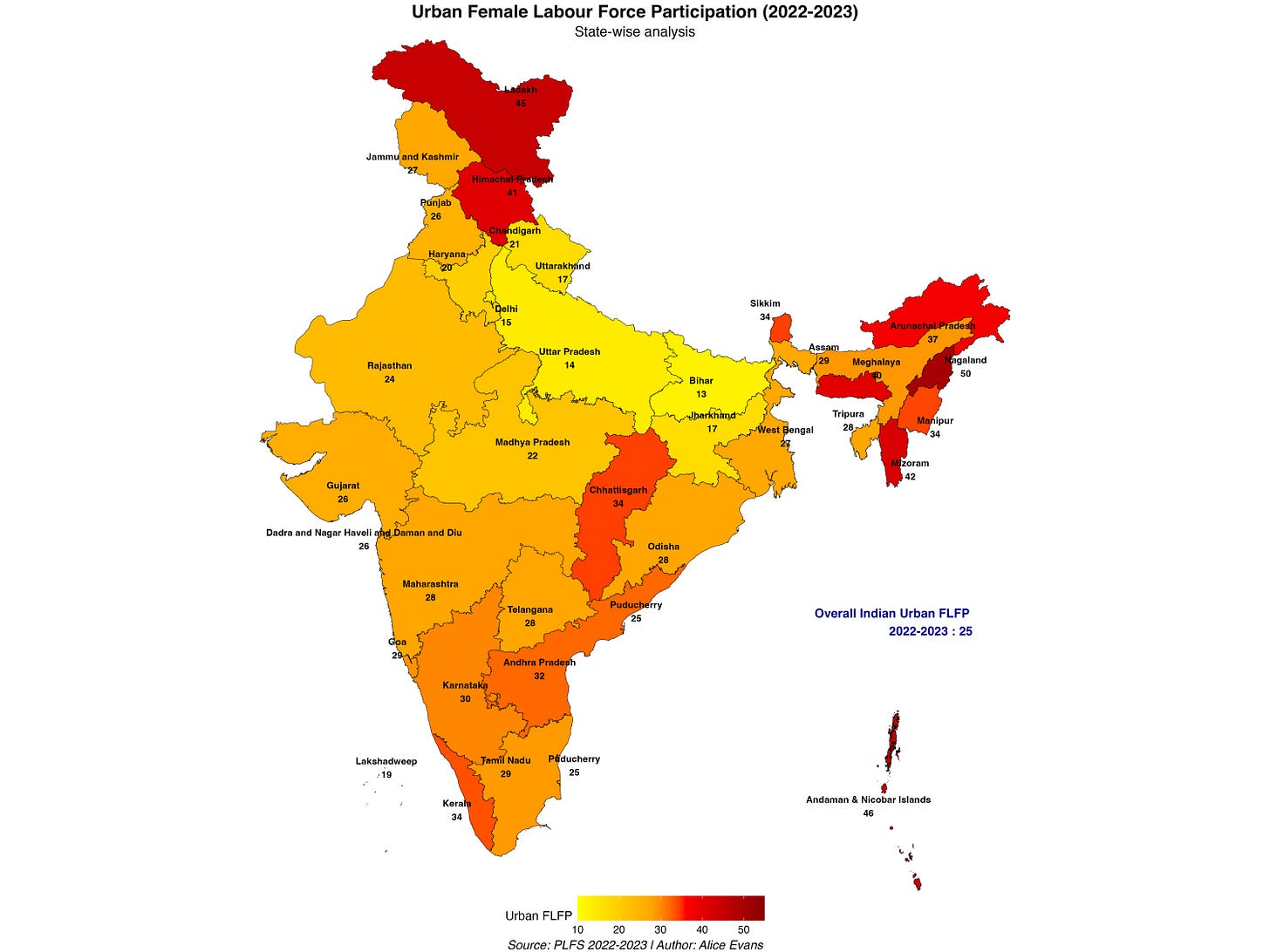

But where Islamic influence was weaker, seclusion was not idealised - as shown by architecture, paintings, and contemporary urban female labour force participation.

Fundamentally, it’s a tale of conquest, prestige and social policing.

The writing is literally on the wall.

Architectural Detectives!

Consider the Rajput palace of Gwalior fort (built in the early 16th century). It features two distinct sections, separated by pierced stone screens (jaali) allowing court ladies to observe rituals whilst remaining hidden - manifesting female seclusion. But did this reflect Rajput tradition or Central Asian influence?

The walls provide our answer - adorned with brilliant blue geometric patterns, quintessentially Indo-Islamic, in vogue since Delhi became the capital of the Ghurid dynasty in 1193. Journey from Meknes to Konya to Samarkand, and you’ll encounter this identical style - a marriage of geometry, Persian domes and glorious bright blue.

Central Asian architecture reflected their ideals of female seclusion, with screened galleries and walled courtyards keeping women away from unrelated men. Concern for modesty even extended to mythology - the 11th century Ghaznavid historian al-ʿUtbi denounced naked deities as ‘lords whose private parts are shamelessly exposed, lacking even a loincloth!’. The Hindu Rajput palace mirrors this cultural package.

Now, this gave me an idea! Can we trace shifting architectural designs more systematically to track the spread of purdah?

Conquest and Cultural Evolution

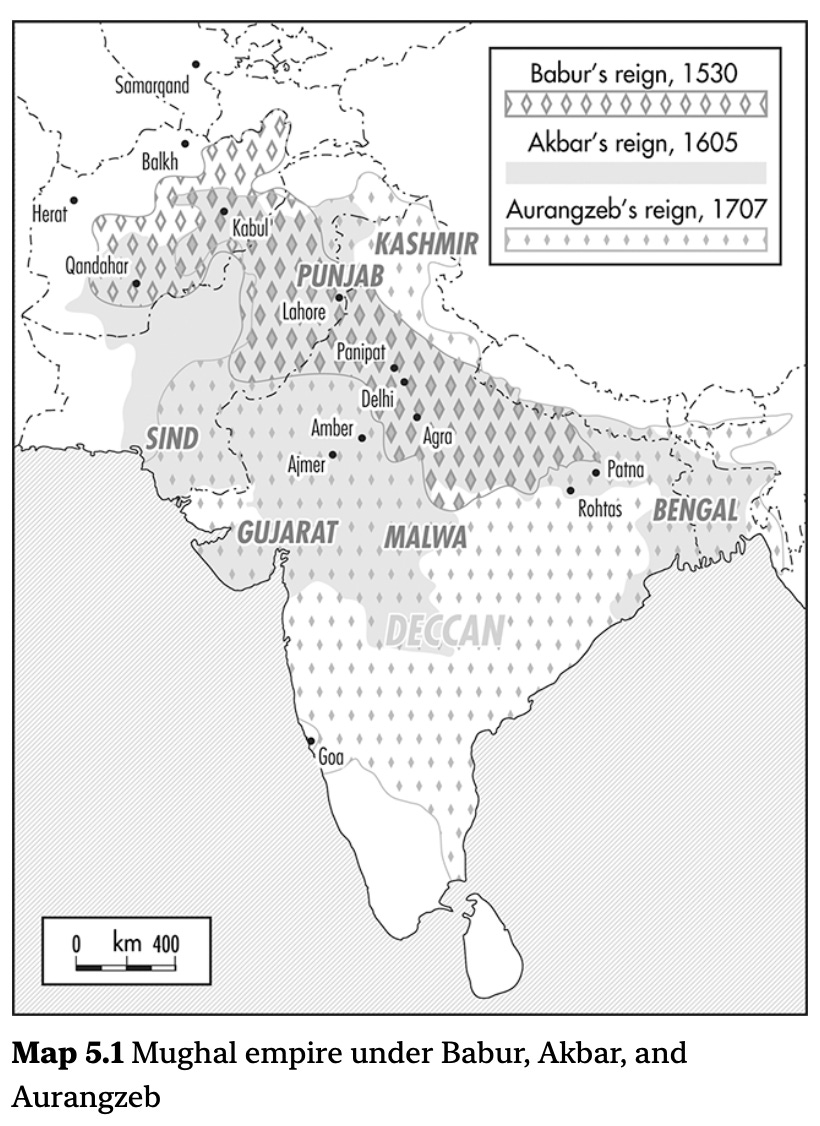

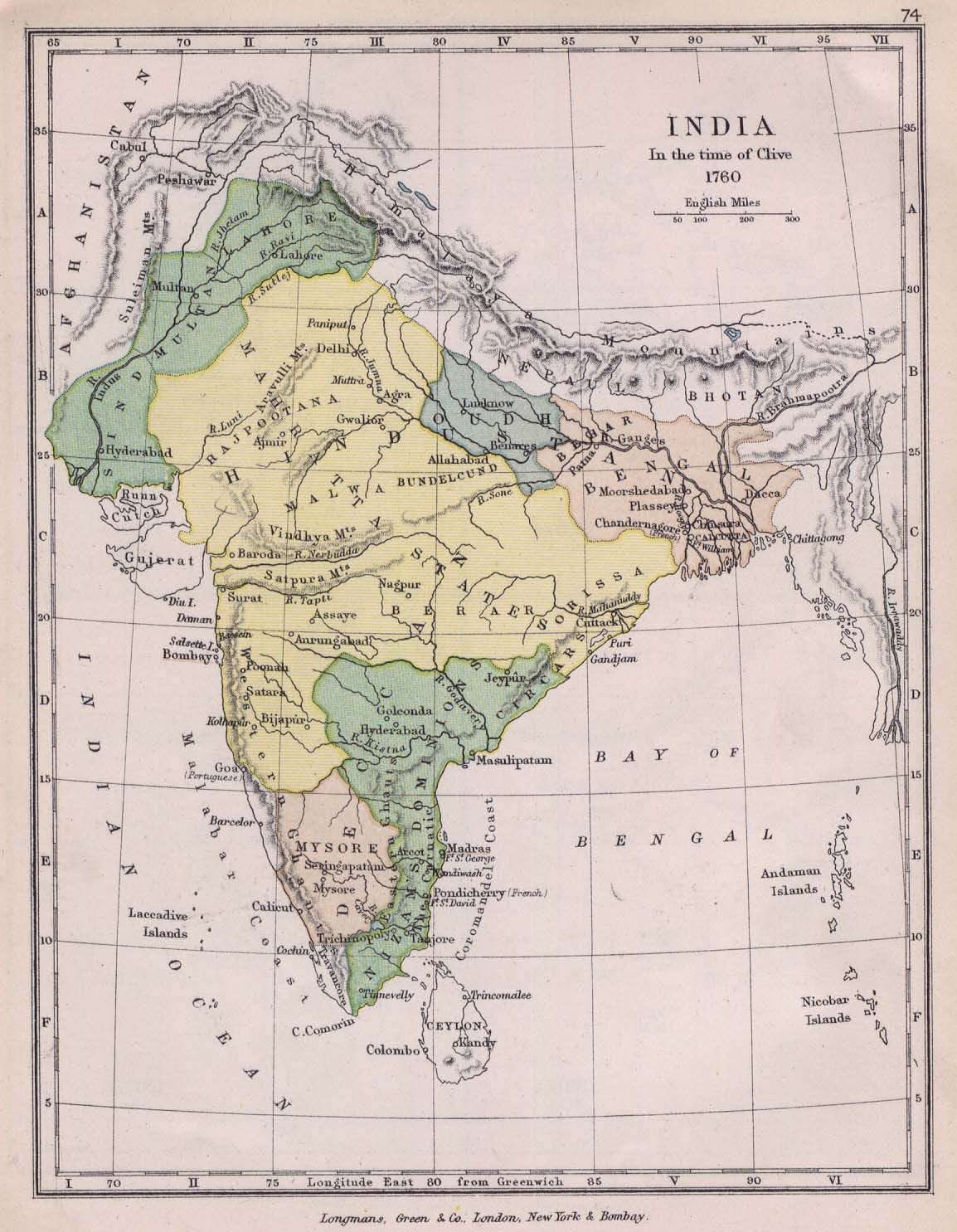

From the 12th century, Central Asian conquerors swept across North India, bringing their customs. The Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) - from the Mamluks through the Khaljis, Tughlaqs, Sayyids, and finally the Afghan Lodhis - established Muslim rule across the Indo-Gangetic plains. Then came the Mughals, invading from modern-day Uzbekistan and defeating the Lodhis at the Battle of Panipat in 1526.

Culturally, Muslim rulers tended to idealise modesty and gender segregation. Even Babur (of Turco-Mongol heritage, who was not very religious, drank heavily, and revered his grandmother’s counsel) still ordered the destruction of naked Jain statues. Akbar, his grandson, was in many ways extremely tolerant and inclusive, yet championed female seclusion.

Akbar’s Promotion of Persian-Islamic Culture

Akbar marked a decisive shift, aligning with stricter ideals of seclusion which were already prevalent across Muslim lands. As Persian administrators, scholars and artists flocked from the poorer Safavid state, Persian culture became the mark of refinement. By the 1600s, scholars needed special dictionaries to understand old Turki texts - a clear sign of how thoroughly Persian had displaced Turco-Mongol traditions.

Persian ethical literature (akhlaq) defined masculine status. Influential texts like Tusi's Akhlâq-e Nâṣeri and Rumi's Masnavi portrayed female sexuality as dangerous to the social order. Men gained respectability by keeping women behind veils and walls.

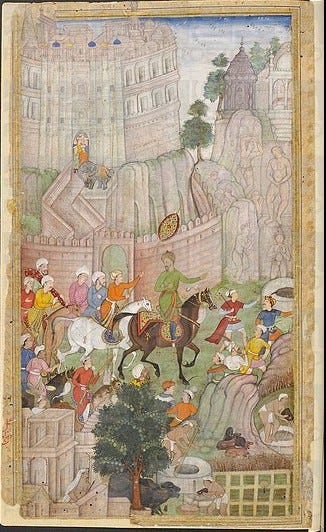

These values were actively promoted via Akbar’s artistic patronage. His painting workshop's first project, the “Tutinama” (Tales of a Parrot), written by an Indian poet in Persian, celebrates female chastity through stories of a parrot preventing a woman’s infidelity. The second illustration shows ‘jaali’, which preserved female modesty.

How Different was Persian Culture?

In the absence of written records, cultural evolution is murky. So we must try to carefully piece together diverse fragments - including architecture.

Genetic data suggests that upper caste populations in the north became much more endogamous around 1600 years ago. That’s when the powerful Gupta Empire enforced moral strictures, under the age of Vedic Brahminism.

The caste system required strict controls on women’s autonomy. Trusted networks of cooperations were cemented by socialising girls to marry within their jati, obey their in-laws and stay put. Divorce and widow remarriage were highly stigmatised, with caste panchayats enforcing conformity with threats of ostracism. In Bengal, clan genealogies (‘kulagranthas’) systematically omitted women’s names - signifying their lower status. Chastity was paramount.

But here we must distinguish between different aspects of patriarchy. Divorce was stigmatised and men were revered as knowledgeable authorities right across Eurasia. What was distinctive, and what strongly predicts gender inequalities today, were Persian-Islamic ideals of female seclusion.

When I manually analysed 10,000 historical Indian artworks, I noticed a striking historical shift: from depicting militant and voluptuous goddesses to emphasising seclusion under the Mughals. Even Hindu scenes incorporated veiling and gender segregation, as exemplified in Mughal paintings of Krishna’s celebration of Holi.

Purdah in Stone

Mughal architecture embodied Persian-Islamic values. At Fatehpur Sikri, gender segregation is maintained through an elaborate system of screened galleries, private courtyards, and interconnected women’s quarters. The Kanch Mahal (east of Akbar’s tomb in Agra) similarly featured lattice screens to enable royal women’s purdah. From the 1580s, imperial princes set up their own harams, staffed by eunuchs, female officials and female servants. Evening entertainment was often held, with women watching through screens.

Life Behind the Screens: Women's Agency in the Mughal Court

Royal women could wield serious influence. Jahangir’s mother hosted crucial ceremonies including royal weddings and weighing rituals where princes were weighed against gold for distribution to the poor. She commissioned major architectural projects including a mosque in Lahore and owned one of the era’s largest ships, used particularly for Hajj pilgrims.

Nur Jahan

Perhaps most remarkable was Nur Jahan, Jahangir's favourite wife. Known for her marksmanship - reportedly killing two lions with a single shot - she wielded significant authority. She minted coins in her name, issued imperial orders, held jagirs (typically male-only land grants), distributed robes of honour to nobles, and received ceremonial drum salutes after the emperor. A skilled poet and patron of literature, she commissioned numerous architectural projects including pleasure gardens, a mosque in Kashmir, and serais (rest houses).

The tradition of powerful royal women continued under Shah Jahan. His daughter Jahanara, serving as leading lady of the court after her mother’s death in 1631, was keeper of the royal seal. A devout Sufi, she wrote a biography of Muin al-Din Chishti, funded his shrine in Ajmer, and provided Agra with its main congregational mosque.

Caution!

Rather than construct a ‘rose-tinted patriarchy’, let me add four key points:

Harems did not just comprise privileged elites, but also enslaved captives. In the early 17th century, one Mughal officer returned from Jessore with 4000 unclothed women. Bengali ballads lament ryots’ (peasant) wives and daughters being seized.

Agency was restricted. Unlike their predecessors, Akbar-era Mughal women could no longer divorce and remarry.

Seclusion was idealised - artists who painted Nur Jahan probably never saw their subject. The Victoria & Albert museum currently has an exhibition on the “Great Mughals”, but cannot name any pictures of women.

Copying the Rajputs, Mughal elite women lost their personal names, identified instead by their place or clan of origin.

Imperial Expansion & Cultural Syncretism

How did these practices spread? Perusing a wealth of historical evidence, I identify four distinct mechanisms:

Persian Culture marked Status

Imperial Expansion

Taxation and Patronage!

Religious Tolerance and Cultural Exchange

Persian Culture Marked Status

By the late 17th century, there was a specific code of gentlemanly behaviour, called mirza'i. Originally denoting Persian/ Timurid ancestry, mirza'i evolved into a broader ideal of sophisticated manhood, codified in conduct manuals like the Mirza Namah. Men demonstrated refinement through knowledge of Persian art and entertainment, which were celebrated in court ceremonies and dress codes.

Imperial Expansion

Akbar actively incorporated Rajputs into the ruling elite. He himself married at least eleven Rajput princesses, while appointing Princes like Raja Man Singh as leading generals.

To maintain control, the Mughals increasingly shared sovereignty with local gentry and merchant groups. This integration extended beyond military and political alliances. Hindus entered schools to learn Persian, seeking employment within the Mughal court, while local power-holders were incorporated as zamindars. This penetrated deep into society - even Hindu scribes needed Persian for advancement. By the 1580s, there were equal numbers of Rajput, Indian Muslim and Persian officers.

As intermediate groups - zamindars, merchants, scribes - grew wealthy from the Mughal economy, mastering Persian culture to unlock social mobility. Consider Chandar Bhan Brahmin, who rose from provincial clerk to state secretary, while mastering Persian poetry and etiquette.

History books provide qualitative insights into Mughal networks and cultural exchange, but I wanted more. Could we be more systematic? Might it be possible to quantify imperial penetration?

Taxation and Patronage!

Taxation reveals the Mughals’ extraordinary capacity for resource extraction and control. In core regions like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the rate of taxation was 35-40% of all agricultural production. In Gujarat, it was even higher.

Intense extraction required sophisticated administration, and here I strongly recommend a wonderful book by Shireen Moosvi. In the late 16th century, Mughals standardised rates (dastūrs) for different crops and regions, developed detailed record-keeping systems, and maintained extensive networks of tax collectors. Three-quarters of government revenue came from land. Of the collected revenue, around 10-25% went to local zamindars. Another 7% to village officials, and about 20% to collection costs. The remainder went to the state.

Regions varied in tax capacity, revealing different levels of Mughal influence. Agra, the imperial centre, typically had the highest rates. In areas where Mughal control was weaker, tax collection could fall to less than half the official rate. Here, local zamindars retained more power and spent more on their own military forces. But where taxation was high, the Mughals had robust mechanisms of control - not just collecting money, but penetrating deep into local administration.

Expenditure was carefully detailed! Over 80% of revenue went to military nobles (mansabdars) as salaries, often paid through land revenue assignments (jagirs) that spread Mughal administration across the empire. But these weren’t independent aristocrats - they were imperial servants, dependent on Akbar's favour.

The imperial household itself consumed only about 5% of revenues, spent on the harem, buildings, precious stones and ornaments. Another portion funded the imperial military, while 5% was stored in the imperial treasury, building up reserves.

By commanding such a large share of agricultural surplus, the Mughals could sustain their military campaigns, massive administration, networks of patronage, and opulent prestige. Craftsmen focused on luxury goods, while an urban service sector catered to the ruling class - all looking up to elite patronage.

Imperial extraction would have crowded out funding for alternative club goods and patronage, making Mughal culture the dominant pathway to status. Prestige bias persisted even after they lost imperial control, as we will discover in the case of Shivaji and the Kayasths.

Religious Tolerance and Cultural Exchange

Upwards mobility did not require religious conversion. Akbar removed the jizya tax on non-Muslims and instituted ‘sulh-i kull’ (peace to all). His court celebrated major Hindu festivals like Dussehra and Diwali, while also commissioning translations of the great Indian epics, the Maharabharata and the Ramayana. Mutual respect is celebrated in the paintings below: “Muslim learns a lesson in piety from a Brahmin”, and “Akbar and the Jesuits.

Exchange flowed through multiple channels - festivals, shrines, bazaars, and marriage networks. In market towns, Hindu and Muslim clerks formed tight-knit circles, sharing drinks while grumbling about social climbers trying to join their ranks.

Cultural borrowing worked both ways - Mughal officer Mirza Nathan even ordered women to perform Hindu rite of jauhar (self-immolation upon defeat), though this had zero basis in Islamic scripture.

Patronage and Brotherhood

Tax collectors, merchants, and marriage parties carried news and customs between towns. While elite Muslims and Hindus shared Persian poetry in their courtyards, farmers and craftsmen mixed at festivals and Sufi shrines. As Bayly observes, “Any set of ideas which helped attract political support, skills or capital was advantageous”. Even today, women of both faiths tie threads at Salim Chishti’s tomb in Fatehpur Sikri, praying for children.

When Akbar died, Jaunpur erupted in chaos until news came of orderly succession - showing how information flowed through these channels. Bazaars buzzed with gossip about the imperial family. All this indicates deep inter-connections

The Spread of Purdah Architecture

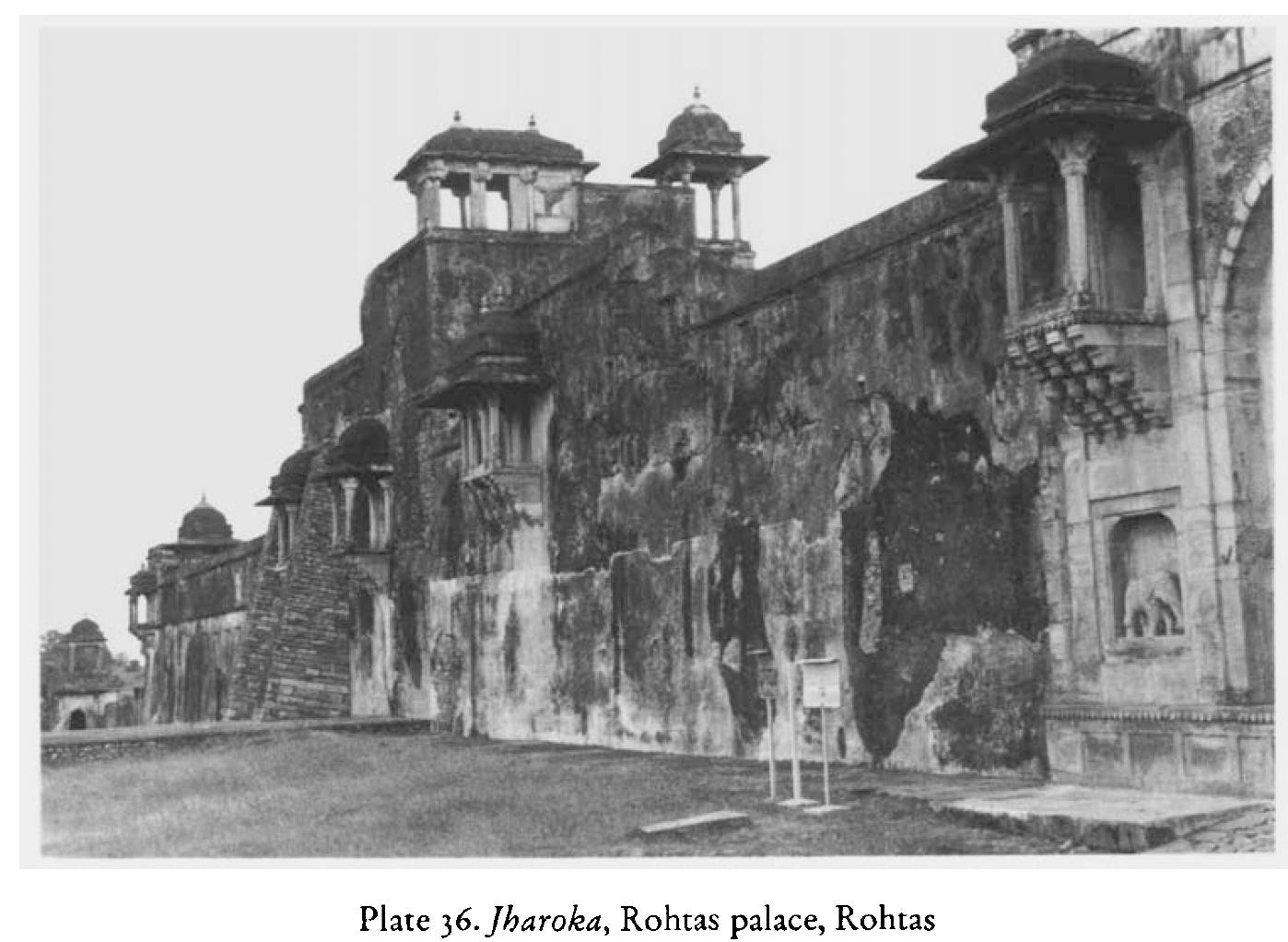

We can trace how these values spread by examining architecture. Hindu nobles began incorporating Mughal designs, seeking to signal their alliance with power.

Raja Man Singh Kachhwaha (1550-1614)

As a Hindu military commander who effectively subdued major revolts in eastern India, he built his palace at Rohtas, Bihar explicitly modeling it on Fatehpur Sikri - a clear signal that he represented Akbar's authority. It also including a zenana (Persian language term for ‘women’s quarters’). His vision extended to his palace in Wah (in contemporary Pakistan), praised for having the ‘perfect’ Mughal pleasure garden, and even to religious architecture - his Govinda Deva Hindu temple incorporated imperial Mughal styles.

Emulation spread throughout Rajasthan

Amber Fort (1592) featured extensive zenana quarters with private courtyards. At Udaipur, an intricate network of screened passages and private quarters allowed royal women to move throughout vast sections of the palace while maintaining strict purdah. Jodhpur's Mehrangarh Fort created an elaborate Zenana Deodi with multiple courtyards and carefully carved windows, enabling hidden observation of ceremonies. This architectural tradition continued into the 18th century - when the City Palace of Jaipur was built in 1729, it included separate zenana wings with private gardens, allowing ladies to view city life from behind screens.

Rajput noblewomen could exert influence, just like their Mughal counterparts. They held jagirs (land grants), commissioned religious buildings, and shaped court politics. But seclusion was idealised - even in art. Women are never shown as individuals. While Rajput courts produced detailed portraits of men, with their distinctive turbans, women are only ever shown as generic dancers, musicians or princesses. Art and architecture served to conceal.

Gender Segregation in the Deccan

The Rangin Mahal in Bidar Fort demonstrates how even regional styles incorporated screening elements and separate women’s sections. In Hyderabad, Golkonda Fort’s zenana quarters feature remarkable acoustic systems that allowed for communication while maintaining physical separation. And this regime explicitly reached out: Qutb Shah rulers issued texts in both Telegu and Persian.

From Palaces to Homes

While elite architectural patterns are well-documented, the evidence is weaker when it comes to more ordinary families - who left little trace. Caution is warranted, but let me share some examples of syncretism.

In fourteenth-century Tughluqabad, Muslim houses featured internal courtyards with Central Asian designs - domes, arches, and Islamic decorative patterns. These homes were carefully designed with public southern sections for male guests and private inner rooms for women, deliberately avoiding windows onto the street.

Grander homes (like that of Kamal Singh) developed sophisticated privacy through clever design - walled rooftop spaces, high pierced stone panels (jaali), and a hierarchy of courtyards where inner areas became progressively more secluded.

Check out this Jat mansion in Bayana. Its terraces were walled with doors opening only to the courtyard side, remaining blind to the exterior except for one carefully placed balcony. This design traced directly back to Emperor Akbar’s residence at Fatehpur Sikri. When aspiring families built new homes, they looked to Mughal elites!

Shivaji adopted Persian Culture

Let me share two striking examples of Hindu elites adopting Persian culture as a mark of prestige bias.

Shivaji, celebrated by many Hindus as the founder of the Maratha Kingdom who attacked the Mughals, actually provides striking evidence of Persian prestige bias. Though proudly Hindu - worshipping the goddess Bhavani and hosting elaborate Sanskrit coronation rituals - Shivaji spoke a language rich in Persian vocabulary and adopted Islamicate dress.

His military included Muslim commanders, and his administration maintained patronage of both Hindu and Muslim institutions.

Paintings show Shivaji wearing the distinctive robes, sash, and regalia associated with Mughal and Deccan rulers. Even the artistic style followed the Deccani sultanate. His grandson Shahu’s court continued this hybrid fashion, with courtiers wearing Persian-style fitted tunics and trousers.

This adoption of Persian culture cannot be explained by theories about wheat or rice cultivation, nor pastoralism, nor more ancient population movements. Instead, it suggests how groups (even antagonists) may emulate elites to prove their own status.

Hindu Kayasths Assimilated

The Hindu Kayasths offer perhaps our clearest evidence of how social mobility drove cultural assimilation. According to the Sahyādri-khaṇḍa, they descended from a Kshatriya prince who was “trained in the arts of the pen rather than the sword”. This origin story affirmed their proud identity, as specialists in administration, law, and accounting, who served Mughal rulers. Alliances were cultivated by maintaining relationships with rulers through gift-giving, court ceremonies, advantageous marriages, and aiding fellow Kayasthas.

Consider the example of the Basu family in 15th century Bengal. Starting as scribes, they rose to high positions under the Sultans by mastering Persian. But Persian proficiency became more than just administrative skill - it marked cultural refinement. Elite Kayasths maintained libraries of Persian literature, adopted Persianate dress and etiquette, appreciated Persian music and poetry, joining a cosmopolitan culture that stretched from Iran into South Asia.

Crucially, while they enthusiastically embraced Persian culture to gain patronage and prestige, Kayasthas remained devout Hindus - building temples, supporting Brahmin scholars, and maintaining Hindu traditions. Kayasths thus played an active role in forging syncretism. In Hyderabad, prominent Kayasth households commonly sponsored both Hindu temples and Muslim shrines, funded mosque maintenance and religious festivals, and created gathering spaces for the community. Many were accomplished Persian and Urdu poets, skillfully blending Hindu and Muslim literary traditions. As one Kayasth poet wrote: “I do not put tilak / It's just another headache / Nor do I perform sejdah / It makes a black spot on my face...I am neither this nor that / I am free in my faith”. The poem captures how Kayasths navigated between Hindu and Muslim cultural spheres - rejecting rigid religious boundaries while maintaining their own distinct identity. Through such cultural synthesis and creating club goods, these influential families helped propagate Persian-Islamic ideals.

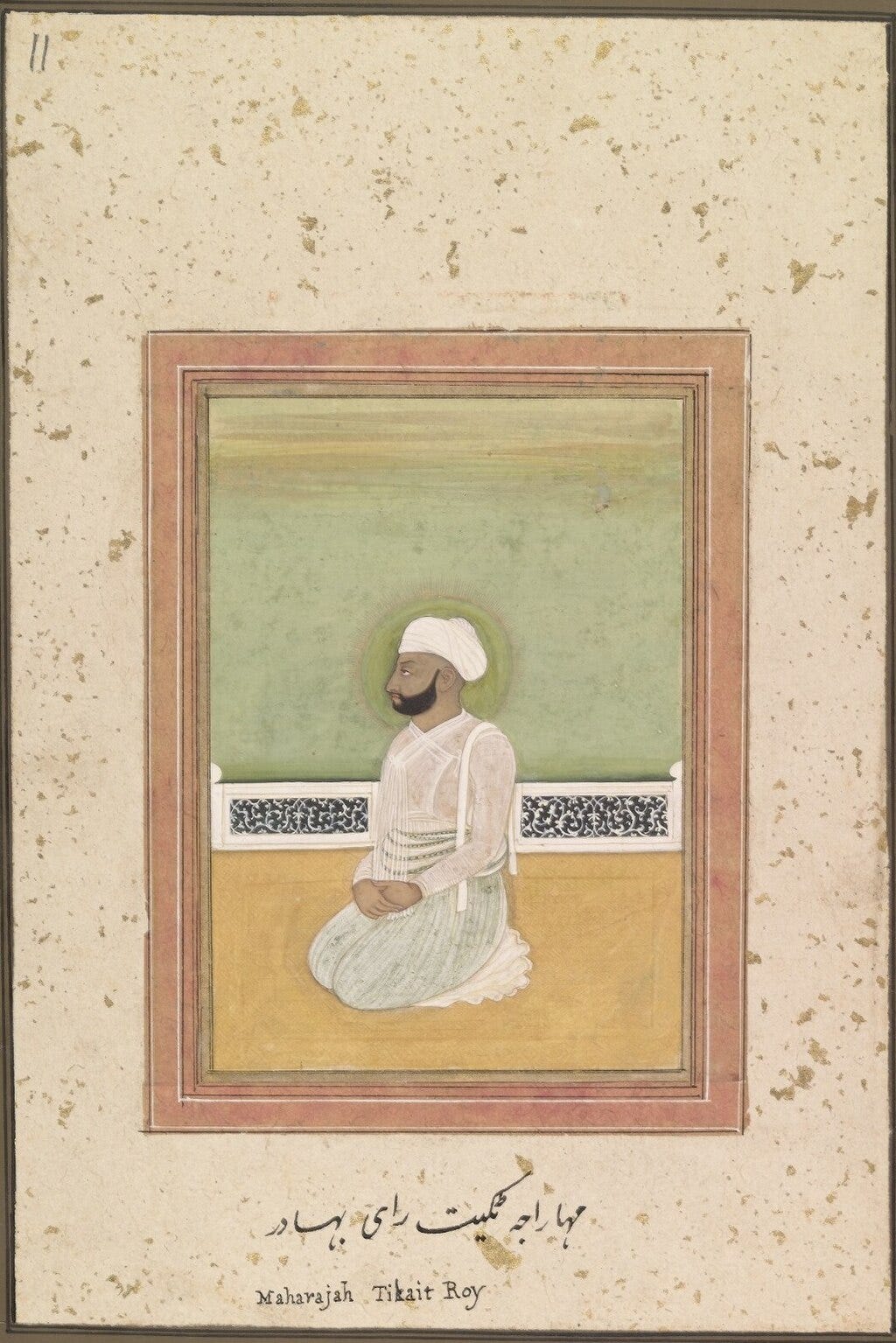

As part of adopting Persian cultural values, Kayasths also embraced female seclusion. The portrait below shows Tikait Rai (c. 1760–1808), the Kayastha Finance Minister of Oudh, whose building projects include a bathing tank, with a separate ‘ghat’ for women.

The 1872 census of Bengal reveals a striking pattern:

“Kayesths are the writer class of these parts and one of the most remarkable... Many of the women can write, and some of them manage their own zemindaries. They are, however, kept in much greater seclusion than the other women of the Rajputs”. The report adds that they were “mostly flesh-eaters” - rather than upper caste vegetarianism.

Ideals of seclusion meant that even though men were highly educated, females lagged behind. By the 1931 census of Agra and Oudh, 70% of Kayesth males were literate - reflecting their roles as scribes - but only 19% of females. Notwithstanding the gender gap, ‘their level of literacy is far and away higher for both males and females than that of any other caste in the province.’

Thus we see how ambitious groups like the Kayasths adopted Persian culture to gain status and patronage, while maintaining their Hindu identity. From architecture to poetry, from segregation to cuisine, elites adopted Persian ideals.

Yet this cultural package did not spread nationwide. As I discovered with dismay, you can’t get decent kulfi south of the Deccan.

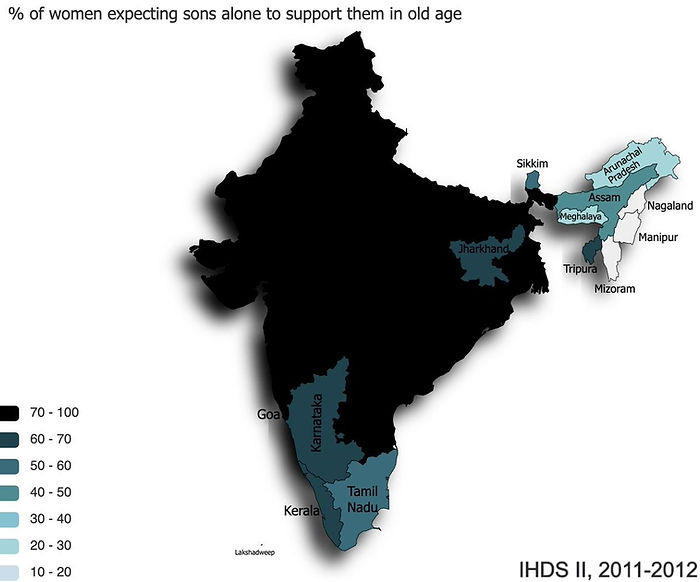

Beyond the Persianate Sphere

The Northeastern Khasi kingdoms

Where mountains created barriers, conquest's reach was limited. While Mughal palaces encoded female seclusion through screened galleries and walled harems, the Khasi of northeastern India maintained radically different arrangements that reflected and reinforced women’s autonomy.

Speaking an Austro-Asiatic language, they were linguistically distinct from the Indo-Aryan plains. Cultural isolation was then preserved through rugged terrain. When Mir Jumla attempted conquest in 1662-63, the combination of monsoon rains, malaria, and challenging terrain forced his retreat.

In this matrilineal society, women were surrounded and supported by kin. The grandmother headed the household, with daughters building houses in their mother’s compound. Property rights reinforced female security - the youngest daughter inherited the family house and could not sell without her sisters’ consent.

Khasi women participated vibrantly in public life. Young women performed ritual dances adorned with jewels and coral beads. While male priests performed sacrifices, they could only do so with female priestesses who controlled the ceremonial items.

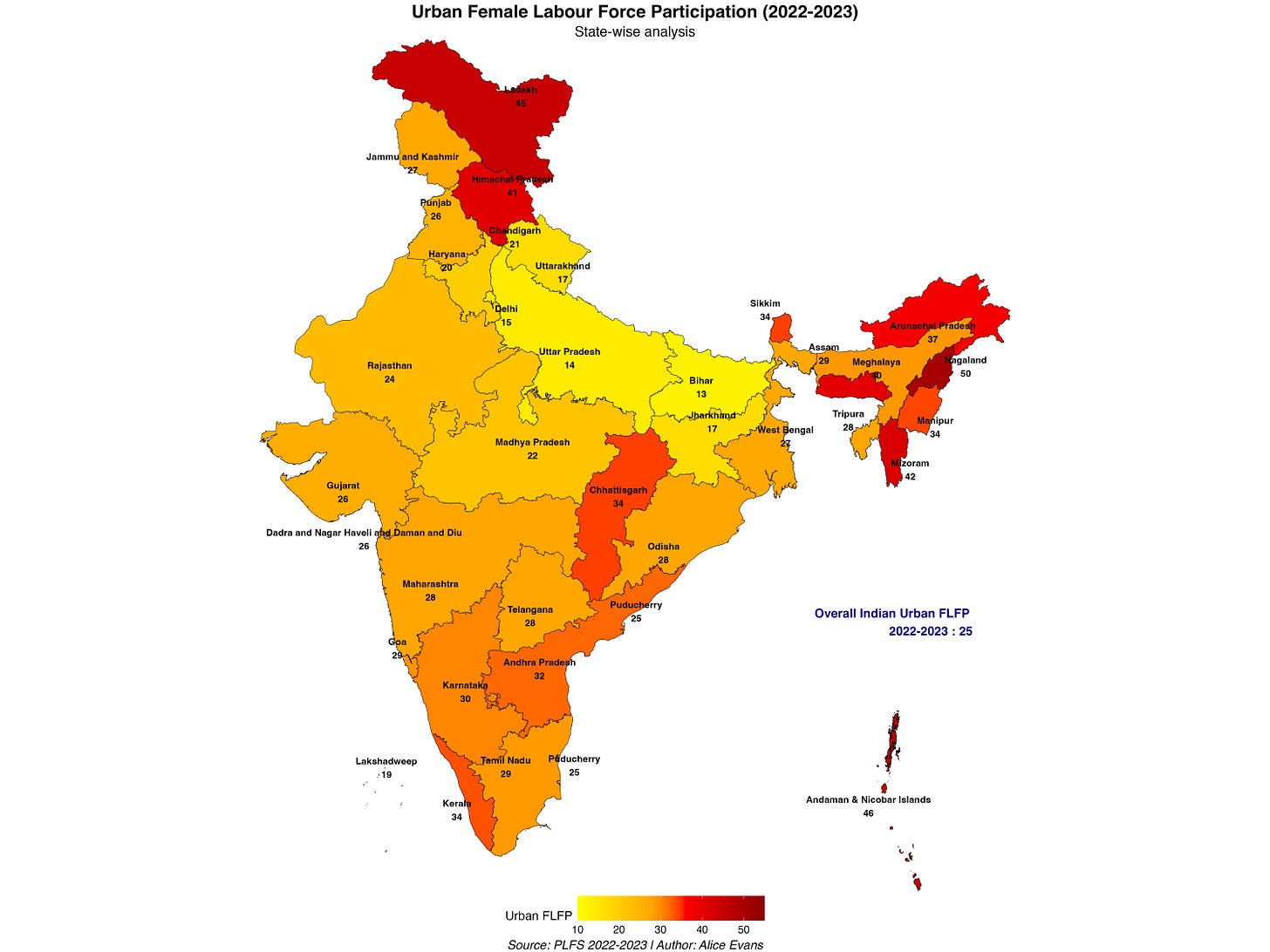

Geographical isolation enabled the preservation of a culture whereby women’s independence was both institutionally protected and publicly celebrated. Today, Meghalaya maintains 40% urban female labor force participation - far exceeding India’s average of 25%.

Kashmir’s Queens

A thousand years ago, Kashmir was ruled by Queens - as detailed in Anjali Verma’s wonderful book, “Women and Society in Early Medieval India”.

In the 10th century, Kashmir king Kṣemagupta was rather weak, so his wife Didda became the de facto head of state. On their coins, the king’s name was prefixed with the letter ‘Di’, i.e. Diddā-Kṣema. After his death, she continued to rule.

Kota Rani (14th century) was the fourth queen to rule Kashmir and the last ruler of the Hindu Lohara dynasty. She was the de facto ruler in place of her husband, Udayanadeva, and continued after his death. She was deposed by Shah Mir (the second Muslim ruler of Kashmir).

Kashmiri women were also respected as local authorities. Verma writes,

‘the state even relied upon their women as governors, feudatories or village heads. Many females acted as successful and popular heads of their respective provinces, districts or villages’.

Geography aided cultural persistence. Mountains protected Kashmir’s Hindu dynasties from conquest, at least until 1346.

South India

Mughal influence was also weak in the South, where women continued to be more publicly prominent. True, a Thanjavur text prescribed similar wifely virtues to those praised in Jahanara’s Agra mosque inscription - wifely chastity and submission. So these regions were certainly casteist and patriarchal, but there is no evidence of female seclusion.

Four women ruled as regents in 16th-17th century Nayaka Madurai (a Telegu dynasty, who ruled much of Tamil Nadu). Rani Mangammal (r. 1691-1706) led her state, using military force and diplomacy to maintain independence against both Mughal and Maratha threats. Mangammal conducted public processions and held court seated on an elevated throne, adorned with gold and jewels.

The contrast extends to visual representation. While Mughal queens’ portraits remained hidden, South Indian royal women appeared prominently in public art. At Madurai’s Minakshi temple, a ceiling painting shows the goddess bestowing royal authority on a queen, with Tamil and Telugu inscriptions affirming her right to rule. Even more striking is Mangammal’s full-body portrait, carved on a temple pillar, with her grandson. She is in full view, as regent.

Sanskritisation

But how did Mughal customs penetrate remote villages, where peasants never glimpsed a Persian nobleman?

Here we need to understand India’s distinctive social hierarchy. As M.N. Srinivas detailed, the varna model of four ranked categories - Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra - evolved gradually during the Vedic period. By around 500 BCE, Brahmin writers had established a divine hierarchy placing themselves at the top, with elaborate codes governing the conduct of different varnas. The three highest varnas were considered ‘twice-born’, entitled to wear the sacred thread and perform Vedic rituals.

But this idealised four-fold system obscured a more complex reality. There were hundreds of jatis (endogamous groups) in each linguistic region of India. Membership was secured through endogamous marriage. Members would preferentially do business with each other, help each other find jobs, provide loans in emergencies, and cooperate in countless daily interactions. Being outcasted meant losing access to these vital networks of mutual support and opportunity.

Higher castes were always ‘pure’ relative to lower castes, maintaining their status through dietary restrictions, marriage rules, and limits on social contact. The structural distance between castes was preserved through elaborate rules of pollution - higher castes could not accept food cooked by lower castes, or marry them, or in some cases even touch them.

This ritual hierarchy created a powerful drive for upward mobility. When lower castes acquired wealth or power, they sought to translate this into higher ritual status by adopting the customs and lifestyle of castes above them. Srinivas terms this ‘Sanskritisation’. Entire jatis (endogamous groups) would collectively adopt upper-caste practices, including female seclusion. A peasant caste might withdraw women from agricultural labor and enforce strict purdah - even at significant economic cost. The local dominant caste served as their immediate model, having themselves adopted these practices from higher ranks. Individuals could not easily resist, as castes policed their own members. If a family allowed their women to work in the fields or move about unveiled, the caste council could declare them outcaste - severing their marriage networks and social ties.

Sanskristation, Technology & Policing in the early 1900s

In 1900, there was a five-day riot in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh. Ten people were killed, shops were closed, the army was called. Medical authorities had removed a Bania widow, diagnosed with plague. As Charu Gupta explains, this was a violation of purdah. To placate massive social unrest, the colonial government stepped back, making exemptions for ‘respectable’ women.

Women’s public visibility and wage earning stained an entire jati. The Agraharis were shunned because their women worked in shops, the Khatiks were stigmatised when their women sold produce on streets, and certain Gujar families were degraded when their women ventured out to trade butter and ghee.

“Purdah was precarious. It was a symbol of the honour and prestige of the middle-class/ upper-caste Hindu household and was sometimes even adopted by intermediate castes to elevate their status” - explains Charu Gupta.

“The sign of high caste women is that.. they do not even allow their women to enter a man’s ears”, asserted Balabodhini, Harishchandra’s journal for women (1874). Jatis seeking upward mobility tightened restrictions. Urban Chamars adopted strict female seclusion. The Khatiks of Lucknow enjoined their women to shops rather than streets. Ahir men stopped their women from going out to sell milk. Even when these restrictions severely hurt household incomes, many jatis prioritised honour.

Technological advances in communication in early 20th century India - with its expanding network of vernacular newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets - enabled Hindu publicists to reach smaller towns and villages. Arya Samaj and Sanatan Dharma organisations condemned women’s public participation as threats to Hindu identity.

In 1870, the Aligarth Institute Gazette urged,

“We wish our women to be educated. But if education means letting them loose to mix with whom they please; if it means that as they rise in learning, they shall deteriorate in morals; if it means the loss of our honour and the invasion of the privacy of our homes; - we prefer our honour to the education of our women, even though we may be called obstinate, and prejudiced, and wrong headed”.

“Make Saraswati [Hindu symbol for women] reside in your house and not a bhand [entertainer] or a prostitute”, pleaded a tract in Haryana. Capitalising on print media, caste associations shamed lower castes for women’s indecency. The Khatri Hitkari Sabha of Agra published pamphlets urging Khatri women to stop singing garis and sithnis [abusive songs] at marriages, considering it a sign of ‘stupidity, shamelessness and uncultured behaviour’. The Agarwal Jati Prabandh insisted that ‘at times of joy and sadness, singing of garis stops immediately’. Similar instructions were repeated by Ahir and Jat publications.

New technologies like railways created fresh anxieties about women’s mobility and behaviour. Caste associations advocated purdah in public spaces like railway stations. Even religious activities came under scrutiny - reformers expressed concern about pilgrimages, claiming that when women spoke freely with pandas and mahants at religious sites, it threatened Hindu honour. Public bathing ghats became another site of anxiety, with calls for separate facilities to maintain caste honour.

Ironically, Hindu publicists repeatedly attributed purdah to Islamic rule, yet simultaneously sought to preserve it.

Sanskritisation helps explain why Persian cultural influence proved so persistent. When Mughal elites promoted female seclusion as a mark of status, the caste system provided ready-made mechanisms for cultural transmission through both prestige bias (emulating higher status groups) and social policing (threatening outcasting). Collectively, jatis emulated purdah, as a marker of prestige. Since marriage networks and economic cooperation depended on good standing within the jati, individuals conformed. Caste councils could enforce purdah through threats of excommunication, creating powerful incentives to forgo female earnings.

21st Century Sanskritisation

Strikingly, new empirical evidence shows these patterns persist in the 21st century. Analysing the 2004-5 and 2011-12 India Human Development Surveys, Reed finds that when families experience upward economic mobility, they significantly increased restrictions on women’s physical mobility and adopted purdah. The effects are especially strong among Dalits and Other Backward Classes, as well as poor or rural communities, and the least-educated. This is strong evidence of Sanskritisation.

The combination of marriage networks, economic interdependence within jatis, and status anxiety still creates powerful incentives for maintaining purdah.

History is not destiny!

In Britain, where casteist policing and purdah-prestige is far weaker, and there are far greater economic opportunities, Hindu women actually have very high rates of employment (58%).

Research ideas:

Conquest, prestige and social policing are the major drivers of cultural evolution. Some forces idealised female seclusion and were militarily successful. As they stormed into new territories and became high status elites, extracting wealth, controlling vast economic resources, monopolising gains, and propagating their values, others emulated to gain status. For centuries, these practices then persisted through desire for status and social inclusion.

I would be keen to see this tested more systematically - though architecture!

Someone clever could use machine learning to analyse Wikipedia’s corpus of historical building descriptions and architectural manuals, mapping features like inner chambers, internal courtyards, purdah walls, and women’s quarters. By coding the time and place of these buildings, one could trace the emergence of purdah! They might then examine whether segregating designs correlate with contemporary female employment.

The Delhi Sultanate’s legacy may be ultra-low rates of urban female labor force participation (Bihar’s at 13%, Uttar Pradesh at 14%, Delhi at 15%).

Related Essays

Excellent Books and Papers

Chatterjee, 2010 “Scribal elites in Sultanate and Mughal Bengal”

Dale, 2011 “India under Mughal Rule” in Morgan and Reid “The Gunpowder Empires”

Moosvi, 2015 “The Economy Of The Mughal Empire C. 1595: A Statistical Study”

Reed, 2022 “The gendered practices of the upwardly mobile in India”

Shokoohy and Shokoohy, 2020 “Bayana: The Sources of Mughal Architecture”

“The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence”

The Victoria & Albert museum in London has a current exhibition on the Mughals. I went with the brilliant historian, Pratinav Anil.

Check out “The Empire Podcast” series on the Mughals. William Darymple and Anita Anand at their finest!

This is an amazing piece, thank you so much for bringing this to my attention. I'm an architect working on (writing about) the connection between architectural design and social systems, focusing on periods of upheaval and trauma. I've traveled to this part of the world and studied its architecture, but had not made the connections you are making about gender (and related seclusion/ hierarchy/ dominance etc) as it is embedded in architectural design. Will this be part of your upcoming book?