Can Big Data Reveal the Origins of Purdah?

In societies where men’s honour depends on keeping their wives secluded, they may deny them permission to get a job or participate in local governance.

So what led to this ideal of female seclusion?

In this essay, I explore thousands of museum exhibits in ‘Google Arts & Culture’ to trace South Asia’s cultural evolution over five millennia. I am analysing this data manually, but hopefully a clever reader will create AI to harness Big Data!

It’s time to ditch the Ethnographic Atlas

Eager to uncover the roots of patriarchy, social scientists have turned to the Ethnographic Atlas. This compiles 19th and early 20th century ethnographies of over a thousand groups worldwide. It includes patrilineal descent, patrilocal residence after marriage, female inheritance, non-monogamous marriage, and cousin marriage. Aggregating this data, Sarah Carmichael and Auke Rijpma construct an index of Family Constraints on Women’s Agency (FCOWA).

Carmichael and Rijpma then explore whether women exercised greater freedoms in societies near the coast, in mountainous regions, or further from centres of plant domestication. They want to see if geography shapes culture.

The Ethnographic Atlas has also been used to examine the effects of pre-industrial agriculture. Esther Boserup famously argued that the plough naturalised female domesticity and subordination, Alesina et al then test this empirically. Meanwhile, Anke Becker explores pastoralism.

But this focus on geography and livelihoods implies there have been NO significant cultural changes between the Neolithic and 19th century! Frankly, I find that unlikely.

If we want to understand the emergence of patriarchy, we need to go back to the earliest evidence, scrutinise every scrap of data, and build a four-dimensional jigsaw, which extends through time and across space.

What historical data is really important?

I suggest we focus on evidence of seclusion. Ancient and Medieval historians rarely adopt this lens, as few recognise its importance for patriarchy in the 21st century. Herein lie the benefits of interdisciplinarity: understand what matters for equality today, then trace its origins!

In this essay, I harness a phenomenal new technology “Google Arts and Culture”. Partnering with thousands of museums worldwide, Google enables us to browse 45,000 items from Russia, 8,900 items from Iran, 11,700 items from Indonesia, 27,100 items from Mexico, and 99,000 items from India.

This map shows all the museums partnering with Google Arts and Culture.

Google Arts & Culture includes 157 museum collections on India.

By examining ancient figurines, early bronze statues, paintings, embroidery, ceramics, literature, as well as vintage and contemporary photos, we can trace cultural evolution over time, attending to subnational heterogeneity.

Pakistan

Pakistan is one of the most patriarchal places in the world.

3% of married women own a house (alone or jointly);

20% say their husbands get jealous or angry if they talk to other men.

39% of married women say they do not participate in decisions concerning their own health care, major household purchases, or visits to family.

47% of women in rural Sind are married to their first cousin.

38% of married 30 year old men justify wife-beating

88% of Muslim Pakistanis say a wife must always obey her husband

Only 26% say a wife should be able to divorce her husband.

84% favour making Sharia the law of the land.

90% say homosexuality is morally wrong.

47% say family planning is morally wrong.

Only 45% say honour killings (over shameful women) are never permissible.

The garment industry’s workforce is just 28% female.

Why is this? Was it entailed by geography, the Neolithic Revolution, the plough, pastoralism, Indo-Aryan migration, conquest by the patriarchal Greeks, or something else?

Join me on this quest to trace cultural evolution over the past 5000 years.

Goddesses in 4th Millennium BC

These two female figurines hail from Quetta (Baluchistan), 3500-3000 BC. They may represent goddesses - since their heads are non-anthropomorphic. Personally, I do not infer anything about gender more widely. The Ancient Greeks worshipped goddesses, but mortal women were secluded, denied rights, and repressed.

These “seated mother goddesses” below come from the Indus Civilisation in Baluchistan, circa 3000-2500 BC. Archaeologist Adam Green suggests that this society was technologically advanced, but relatively egalitarian. Gender roles remain unclear.

This is a terracotta female figure from Mohenjodaro (2700 BC - 2100 BC). India’s National Museum in New Delhi labels it ‘Standing Mother Goddess’. She is only wearing jewellery, a headdress, and a short skirt. Her partial nudity is doubly revealing: it suggests scant concern for female modesty.

Fertility Goddess in 3rd millennium BC

The MET labels this “fertility goddess” from Baluchistan, circa 2700–3000 BCE.

Some scholars believe that fertility rituals and goddesses indicate appreciation for social reproduction, which contemporary societies tend to devalue.

I am unsure. Before modern medicine, maternity was incredibly dangerous yet nonetheless necessary for group survival. The glorification of fertility may have encouraged women to take health risks and have more babies.

Women may have also prayed to this goddess in desperation - for safe labour. Either way, I am not convinced fertility goddesses reflect women’s status.

Sexuality in 3rd millennium BC

This couple comes from Baluchistan, 2700–3000 BCE. In the absence of writing, it’s impossible to know what this represents. Maybe it is the world’s first pornography?

Indo-Aryan Migration

After 3300 BCE, Yamnaya pastoralists erupted out of the Pontic Steppe, armed with wagons and battle axes. They glorified brutish masculinity, butchered indigenous men, reproduced with the women, and imposed patrilineal clans. Genetic evidence demonstrates that five thousand years ago, some male lineages had enormous reproductive success.

4000 years ago, Sintashta Steppe men migrated to the Indus Valley Civilisation and reproduced with local women, to formed Ancestral North Indians. South Asian steppe ancestry largely comes from males. Steppe men reproduced with local women.

Linguistic data is consistent with genomics. The vast majority of Pakistanis also speaks Indo-Aryan languages: e.g. Kashmiri, Punjabi, and Sindhi.

Now, we can trace ancient figurines: did the Sintashta-Steppe migration herald to a step-change in male-domination and female seclusion?

Gandhara

In 330 B.C., Alexander the Great conquered Gandhara (in what is now Pakistan). Did Hellenistic influence bring patriarchy? Not as far as I am aware, none of the remaining art and iconography indicates female seclusion.

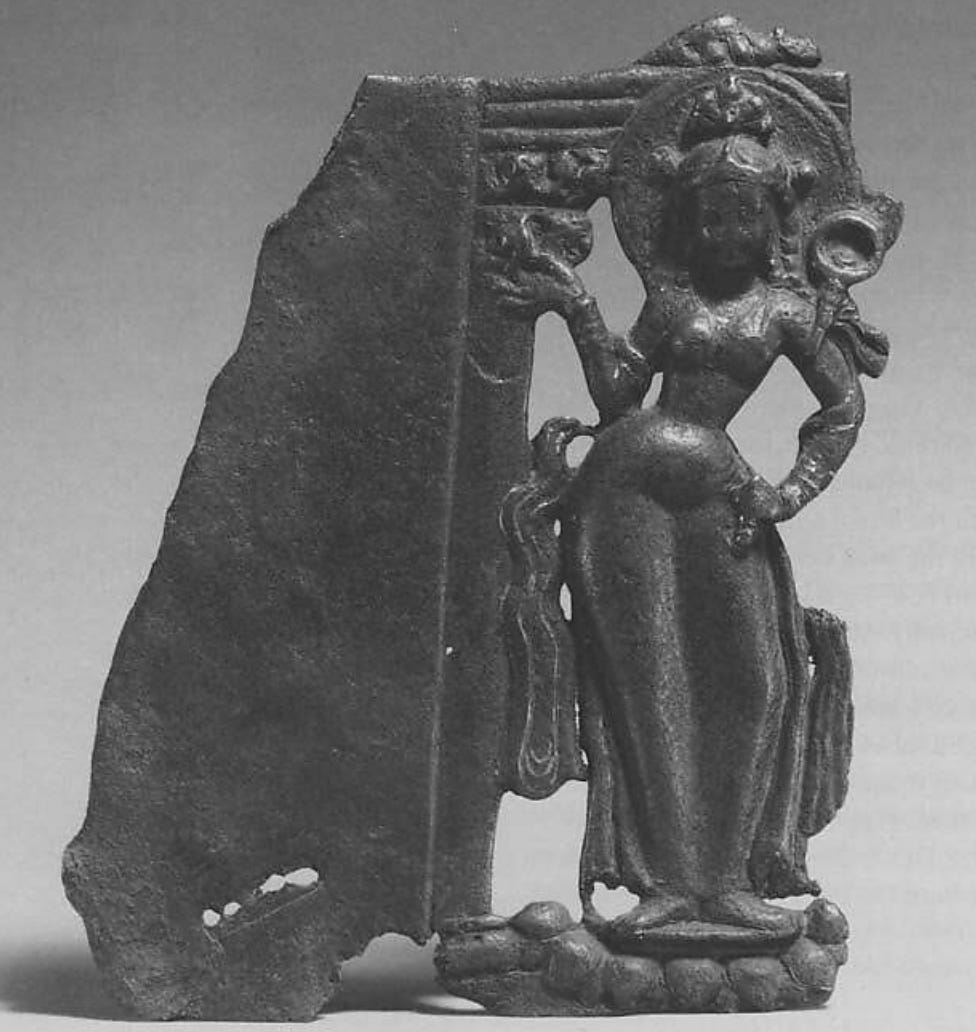

This fragment, possibly a mother goddess, may indicate female status. It is from Gandhara, 2nd century BCE.

This mythological couple (maybe Daphne and Apollo) comes from Gandhara, 2nd century CE). Like all other Indian art from this period, it combines spirituality and sexuality. Lust was not seen as something terrible that ought to be repressed.

Hellenistic influence continued in art - like this depiction of noble lady from Rokhri in District Mianwali (Punjab). There is no indication of modesty or veiling.

This Hellenistic statue shows a young lady, with visibly curly hair. There is no indication of modesty or seclusion. She comes from Akhnoor (Kasmir), 7-8th century CE

This mirror handle depicts an ordinary woman, unveiled in 1st century BCE.

This statue from 100 CE (Gandhara) depicts a male and female musician, dressed in a Greek style. It does not indicate restrictions on mixed gender socialising.

This pendant (from Pakistan in 100s CE) blends local and Hellenistic deities, symbolising abundance and prosperity. In India, the lotus flower is associated with the goddess of good fortune, Shri.

Buddhism

Chandragupta Maurya founded the strong, centralised Mauryan Empire, which spanned much of India. His grandson (Emperor Ashoka) converted to Buddhism and despatched Buddhist missionaries to Gandhara in 3rd century CE. This region became a major centre of Buddhism.

During early Indian Buddhism, women could become nuns (bhikṣuṇī). Monks were still superior, but women were certainly not restricted from public spirituality. They continued to move freely and participate in congregational worship.

Hariti, protector of children

The “mother and child” ideal has been celebrated by many patriarchal societies, but the Buddhist goddess Hariti was a little different. She was originally a child-devouring demon, then the Buddha enabled her to become their ‘protector’. Her cult was especially popular in ancient Gandhara.

The statue below is from 1st century BC Gandhara. Bare-breasted and unashamed, as well as independently powerful, there is no indication of female modesty.

Sexuality

Early Indian art celebrated sexuality. It was not scorned as sinful, shameful or a catalyst of social discord. Almost every temple bears witness to the intertwining of music, dance, spirituality and sexuality. This mirror handle of a fornicating couple comes from Gandhara (1st Century BC- 1st Century CE).

This female head comes from Gandhara, 3rd–4th century.

Still no indication of female modesty.

The Gupta Empire, 4th-6th century CE

Upper caste populations in the north became much more endogamous around 1600 years ago, estimate Basu et al. That’s when the powerful Gupta Empire enforced moral strictures, under the age of Vedic Brahminism. Caste endogamy required tight controls on female sexuality and reproduction.

Outside the Gupta empire, there was still admixture (especially among tribals).

In the early medieval period, Hindu smriti commentators decreed that women and lower castes could not achieve spiritual enlightenment. Conservative ideals were strongest in the north, and more contested in the south (where women also co-ruled).

Women’s Public Roles in the 7th Century

In the 7th Century, a Chinese Buddhist monk named Xuanzang traversed India, journeying to Punjab, Sindh and Kashmir. He saw both Buddhists and Hindus. What did he observe about gender?

Multan’s Hindu Sun Temple [a renowned site of Hindu pilgrimage] was ‘very magnificent and profusely decorated’. ‘Women play their music, light their torches, offer their flowers and perfumes to honour it’.

This is important! Women were still prominent in congregational worship.

In Sindh, Xuanzang observed that there are

‘several hundreds of thousands of families settled. They of an unfeeling and hasty temper, and are given to bloodshed only. They give themselves exclusively to tending cattle, and from this derive their livelihood. They have no masters, and, whether men or women, have neither rich nor poor; they shave their heads and wear the Kashaya robes of Bhikshus, whom they resemble outwardly while they engage themselves in the ordinary affairs of lay life’

This portrayal of conflict-prone pastoralists is consistent with new research by Yiming Cao and colleagues. In the absence of state protection, pastoralists may have needed to project brutal masculinity so that no one stole their precious herds.

However, this description of identically-dressed men and women sharply contrasts with Anke Becker’s finding that contemporary pastoralists tend to impose tight patriarchal restrictions. Perhaps female seclusion is not inherent to pastoralism, but a more recent cultural innovation.

Buddhist & Hindu Goddesses, 7th-9th centuries

In the 7th and 9th centuries, Buddhist and Hindu goddesses were depicted as strong, assertive, and scantily clad.

Tara was the most powerful goddess in the Buddhist pantheon. This bronze is from the Swat Valley, 7th century.

Tara is now standing. This is also from Swat Valley, 9th century.

This sculpture shows Hindu goddess Durga slaying the buffalo demon (7th century, Kashmir). With her leg on top of the slain foe, she is bold and defiant.

This 9th century sculpture of Durga is similarly bold, also from Kashmir. Like other Indian art from this period, she is not veiled, but has rather prominent pert breasts.

Another 7th century deity, from what is now Pakistan. No indication of modesty.

This crowned, defiant, militant goddess holds a sword and a severed goat’s head. She may represent Sarada (the Kashmiri goddess of learning). She towers above two small men. 9th century, Kashmir.

Shiva and Parvati are depicted below, with their sons Karttikeya and Ganesha and the Calf Bull. Crowned, they resemble Kashmir’s track record of female rulers and regents. This is from the 9th century.

Pavarti is wearing very thin fabric, revealing every curve.

Kashmir’s Queens

A thousand years ago, Kashmir was ruled by Queens - as detailed in Anjali Verma’s wonderful book, “Women and Society in Early Medieval India”.

10th century Kashmir king Kṣemagupta was rather weak, so his wife Didda became the de facto head of state. On their coins, the king’s name was prefixed with the letter ‘Di’, i.e. Diddā-Kṣema. After his death, she continued to rule.

Kota Rani (14th century) was the fourth queen to rule Kashmire and the last ruler of the Hindu Lohara dynasty. She was the de facto ruler in place of her husband, Udayanadeva, and continued after his death. She was deposed by Shah Mir (the second Muslim ruler of Kashmir).

Kashmiri women were also respected as local authorities. Verma writes,

‘the state even relied upon their women as governors, feudatories or village heads. Many females acted as successful and popular heads of their respective provinces, districts or villages’.

Geography aided cultural persistence. Mountains protected Kashmir’s Hindu dynasties from conquest, at least until 1346.

Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates

A century after the death of Prophet Muhammed, Muslim armies had conquered the entire Middle East, North Africa, Spain, Tansoxania and the Sind. A minority of Arab Muslims then ruled native Hindus and Buddhists. Multan in the Punjab also came under the control of the Ummayad and Abbasid Caliphates.

They were succeeded by the Central Asian Ghaznavids (977–1186), Ghurids (786–1215), and Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526). These new Muslim states were run by Persian bureaucrats and Turkic slave soldiers. Waves of missionaries and Sufi saints came to encourage conversions and establish madrasahs.

Rumi and Tusi (two Islamic Persian ethicists) were widely revered by Central Asian rulers and missionaries. Rumi’s Masnavi was celebrated by Sufi saints who travelled to the Delhi Sultanate, and subsequently became a firm favourite of Mughal Emperor Akbar. Tusi’s Akhlâq-e Nâṣeri also became part of the Mughal madrasa syllabi.

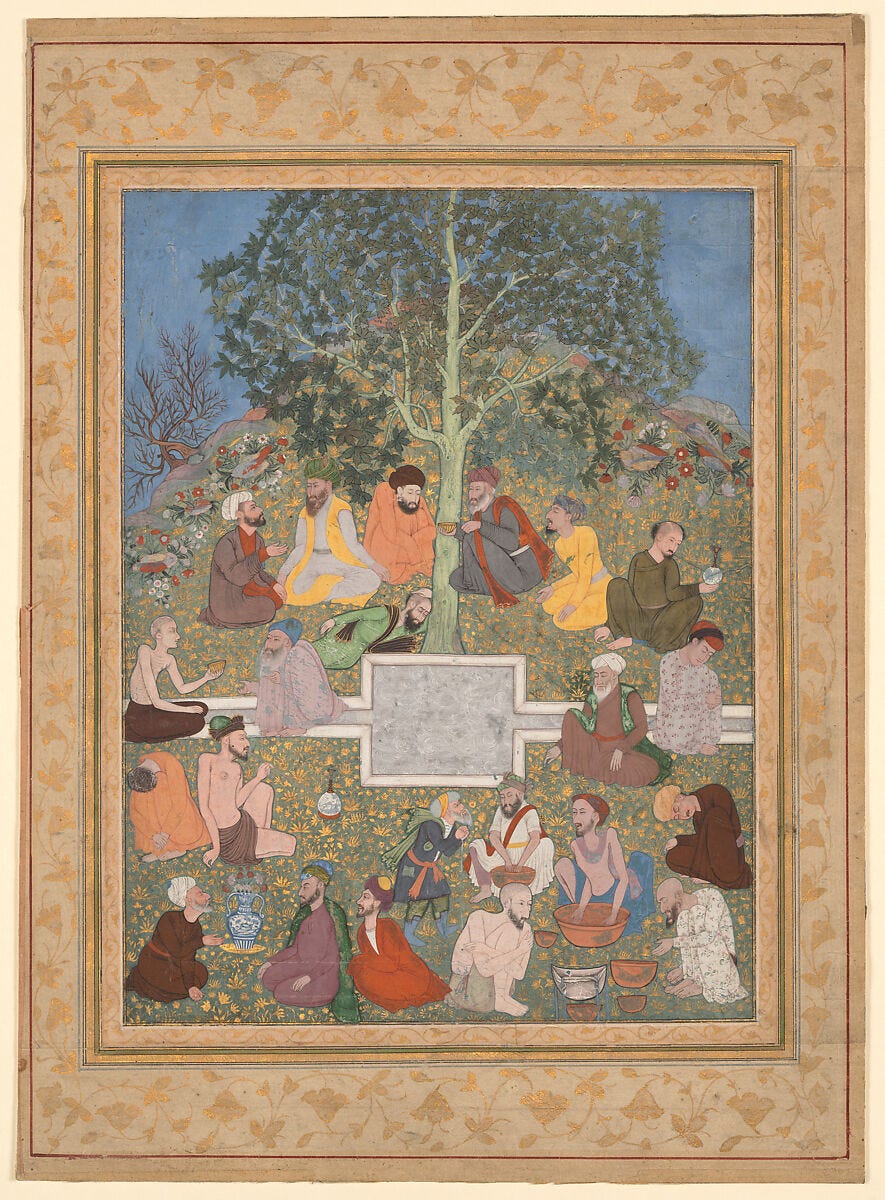

The painting below shows ‘A Gathering of Dervishes’ (1605-1610). Men (and men alone) gained ethical refinement and fraternal solidarity by partaking in these spiritual rituals, bonding in unity. This male dominated public sphere contrasts with earlier observations of women’s participation in religious rituals.

Muslim rulers introduced some reforms that may have improved women’s welfare, such as periodically banning sati and permitting widow remarriage.

However, Muslim also preached gender segregation. Tusi and Rumi (the most celebrated Islamic ethicists) maintained that men gained ethical refinement by keeping their wives secluded and subordinate. Women’s dancing in public was banned, as was the sale of wine. Hindu and Muslim women increasing retreated from the public sphere. This was motivated by both prestige bias (copying elites) and also the horror of slave-raids.

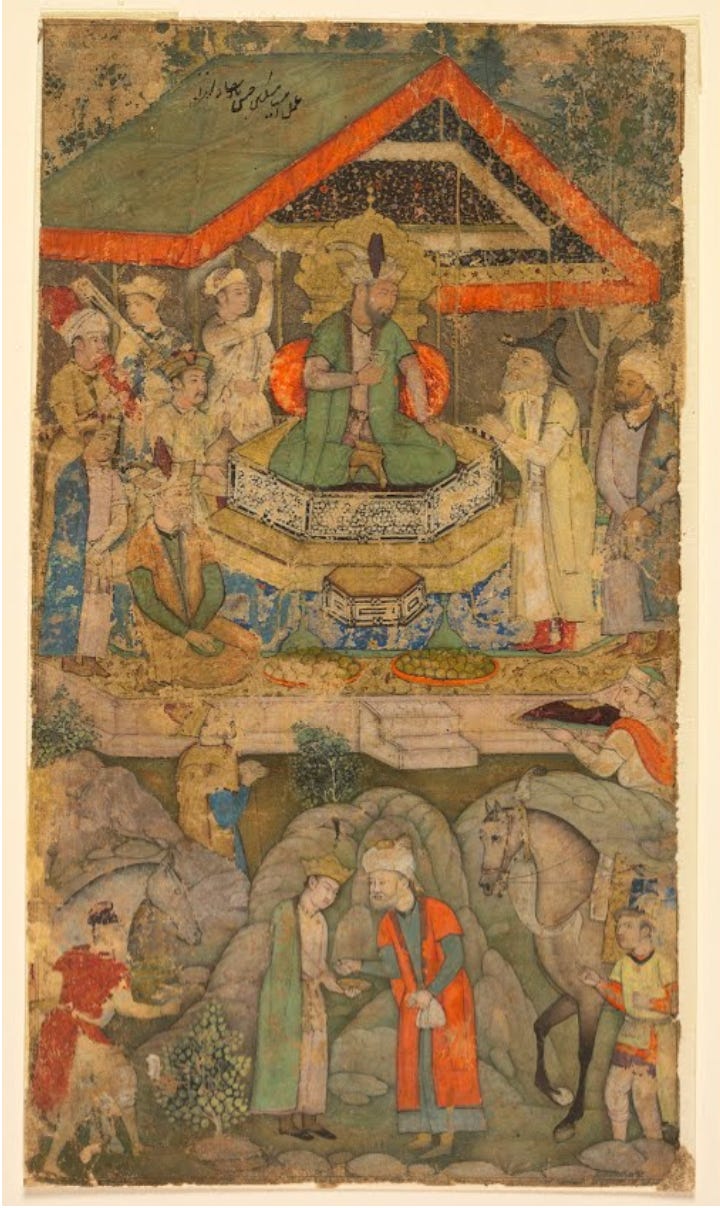

When I visited the Timurid Museum in Uzbekistan, I noticed that the public sphere was exclusively male. Mughal paintings are precisely the same. This 16th century painting shows Timur distributing gifts from his grandson. Women are absent.

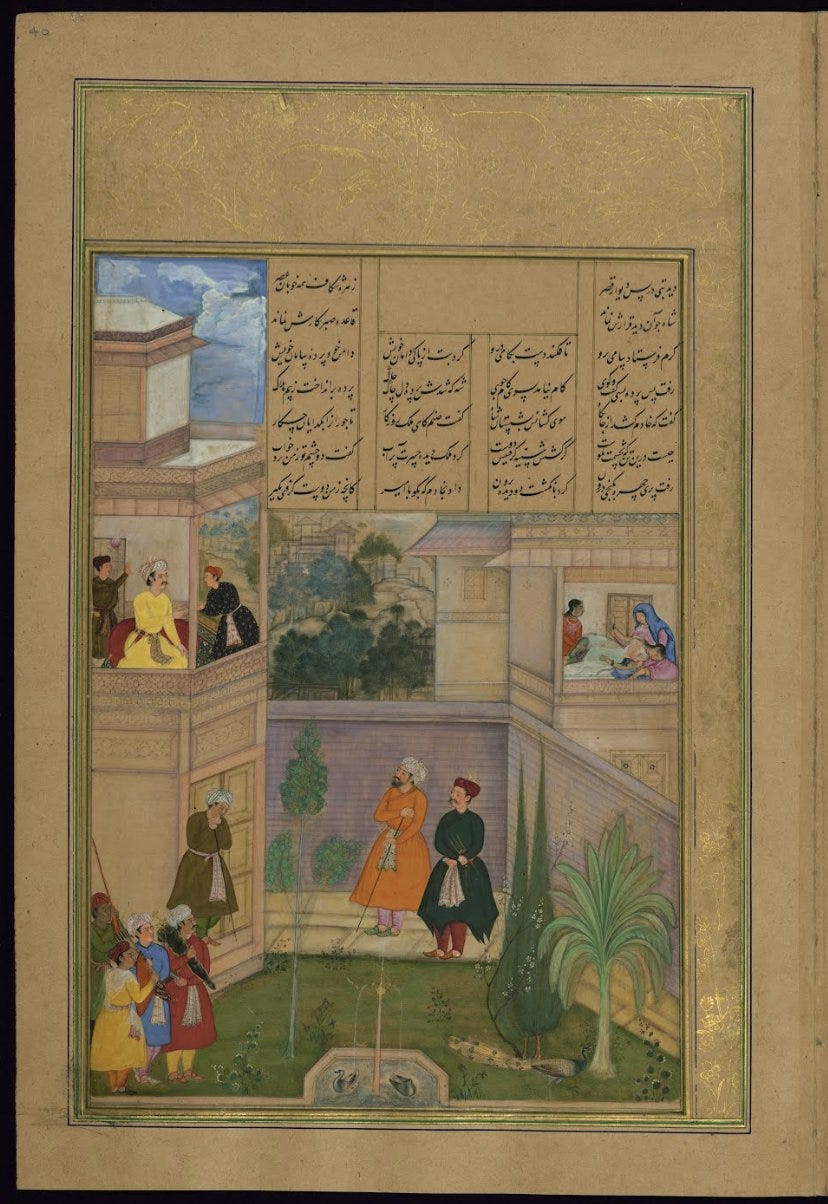

This illustration is from a ‘History of Akbar’. There is dancing and merriment, while women are notably absent.

This exquisite 17th century plate shows Mughal Emperor Shah-Jahan receiving his three eldest sons during his accession ceremonies. The public audience is entirely male.

This 16th century painting depicts Akbar visiting the tomb of Khwajah Mu'in ad-Din Chishti at Ajmer. It’s bustling with sprightly energy; a plethora of personalities. All male.

This 16th century painting depicts an ambassador before, Humayun, the second Mughal emperor of India. The crowd is exclusively male.

This painting from Lahore (1598) tells of a woman who is being pursued by the king, who claims he cannot resist her beautiful eyes. To escape his advances, she plucks out her own eyes, and sends them to him. She prioritises virtue.

In this 18th century painting, on display in Lahore, a noble man supervises construction work. All workers are male.

This 17th century painting depicts ‘Akbar and the Jesuits’ - reflecting his curiosity about other religions. The congregation is entirely male.

In this marriage procession from Himachal Pradesh (1640), the public domain is entirely male.

Zoom in, you’ll see women watching from balconies. This evidence undermines claims that British imperialism introduced patriarchy to India.

This painting from 1670 depicts male-only socialising. Listening to music, they bond together in fraternity. Male homosocial love was likewise celebrated by Tusi (the popular Islamic ethicist).

Veiling was imposed on Hindu mythology

In Patna, I visited an amazing exhibition on three millennia of Hindu goddesses. Perusing their vast collection and visiting many ancient temples, it seems that pre-Mughal Hindu deities were always unveiled.

In Mughal paintings, Hindu goddesses are suddenly wearing a ghoonghat (veil). In some paintings they are also shown on a higher floor, or different part of the house. This reflects Rumi’s ideals of gender segregation. But there is subnational heterogeneity. In Indian districts where Mughal influence was limited, Hindu goddesses remain unveiled. This evidence suggests that Hindus adopted ghoonghat as prestige bias, then glorified ghoonghat as their own Hindu culture. As far as I am aware, I am the first to highlight this cultural shift.

In this 1780 miniature, Krishna plays his flute to a row of gopis (milkmaids who are devoted to Krishna). They are all veiled.

This Mughal-era miniature depicts Krishna playing Holi. The women are veiled and on an upper floor, away from the men.

Qualitative observations attests to gender segregation. When Scottish surgeon James Burne visited Sind in 1810, he was asked to inspect a young woman:

“It was proposed that I should meet her in a garden, with a wall about five feet high between us; but as I objected to this mode of examining a patient”.

This 19th century painting depicts Lord Krishna leading Lady Rukmini in his gleaming chariot. The women are veiled.

In this 1825 painting of Hindu mythology, Radha and her companion are both veiled.

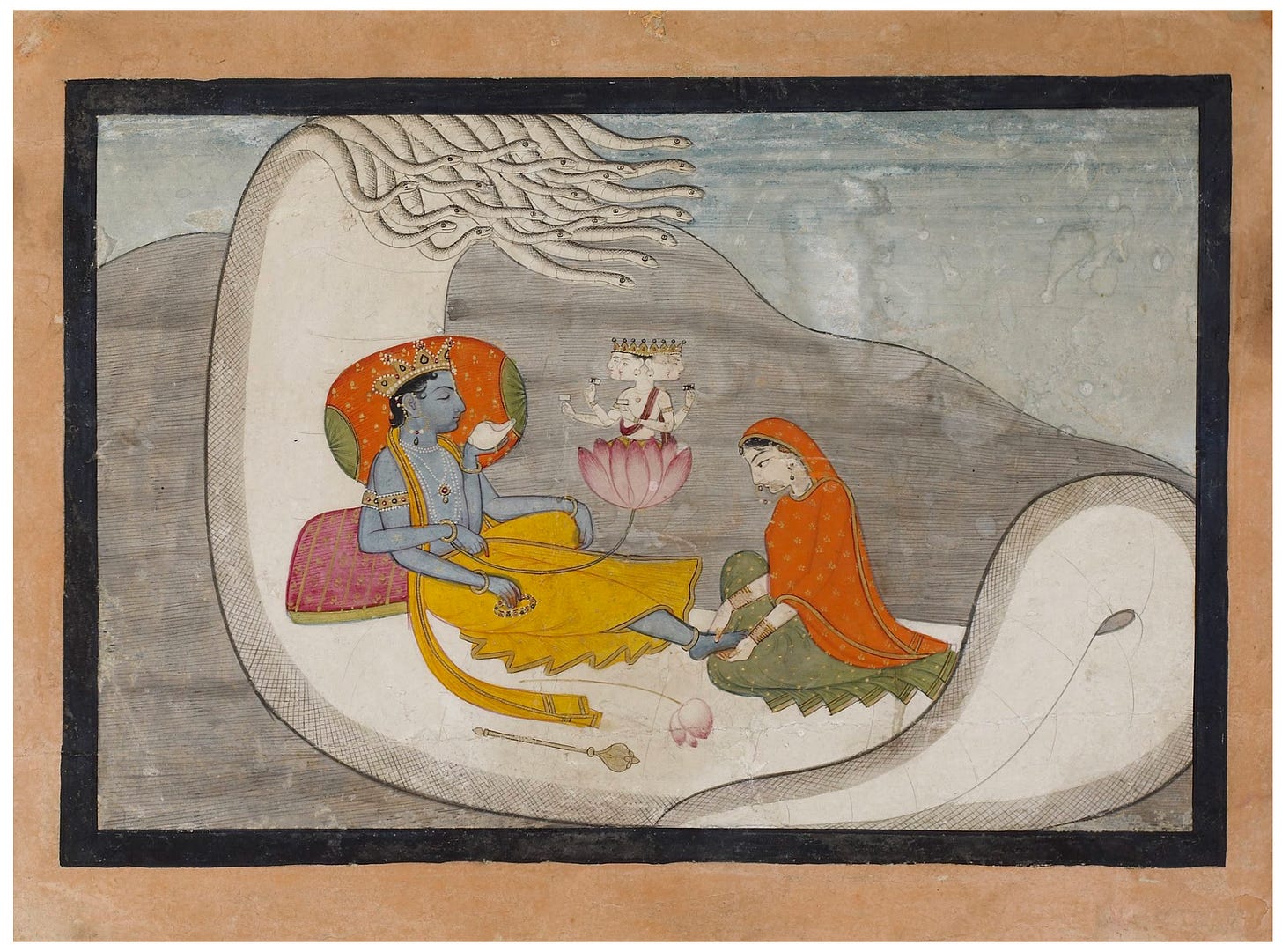

In this late 18th century painting of Vishnu reclining on the serpent, we again see veiling.

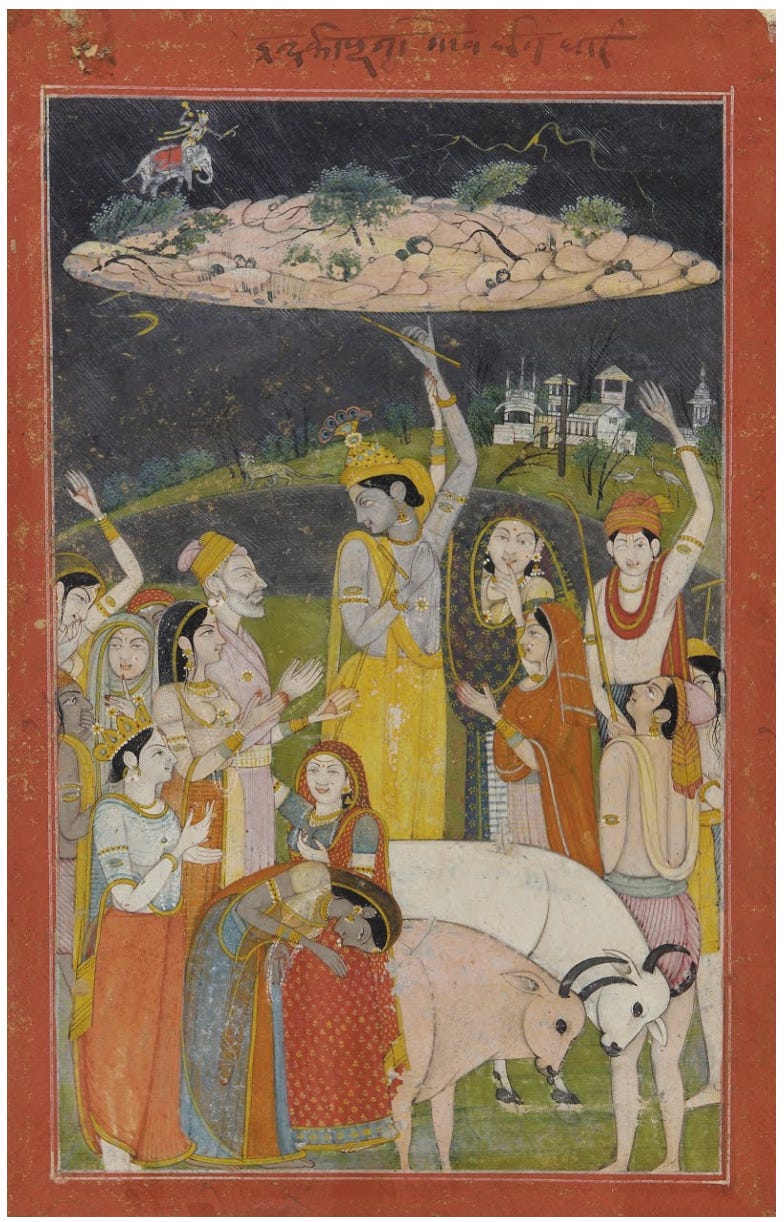

Mola Ram’s painting of ‘Krishna Holding Mount Govardhan’ (1790) depicts women as veiled.

This illustration from an 18th century Mahabharata depicts gender segregation and veiling. Men eat separately.

This 1790 painting shows ‘The Churning of the Ocean of Milk’; women are veiled and on a higher level.

In this early 18th century painting of Rama and Sita’s marriage, the women are veiled. Two more women are indoors, on an upper floor.

In Abanindranath Tagore’s 1905 painting, ‘Bharatmata’ (Mother India) is veiled.

Contemporary Indian art sometimes projects veiling into Hindu mythology

Mughal customs continue. This watercolour by Calcutta artist Sunayani Devi depicts Radha and Krisna.

This Chamba embroidery also incorporates veiling, as part of Hindu mythology.

Did Durga become more gentle?

Before the 14th century, North Indian goddesses were often represented as unashamed and militant. While this does not necessarily reflect wider gender relations, it starkly contrasts with Mughal-era portrayals.

In this Mughal-style painting, Durgha is sedate, calm, and veiled. Her companions walk slowly in their floor-length (rather impractical) dresses.

Hindu goddess remain much more defiant in Indian art that did not adopt Mughal aesthetic or cultural norms.

This 19th century Durga is from Western India. It is not in the Mughal style. Her breasts, belly button and inner thighs are fully exposed. She is militant. Durga annihilates the demon Mahisha.

Sita is glorified as the model of female devotion, put under trial by the citizens of Ayoda to prove her faithfulness to Rama. The Ramayana is no feminist utopia. Sita endures intense social policing about her chastity, and this has been celebrated for millennia.

However, there is a big difference between ideals of chastity and seclusion. Seclusion inhibits women’s mobility in the public sphere. That’s why Pakistan’s garment industry is only 25% female.

This leather scroll from Telugu shows key stages of Sita’s life, starting with her marriage. All women are unveiled, none are on a separate floor. This is consistent with Telugu women’s greater mobility and labour market participation.

This 17th century painting of the Ramayana is not in the Mughal style and women are clearly unveiled. depiction of scenes from the Ramayana

In this 16th century Keralan sculpture of Rama and Sita, she is again unveiled.

Since Keralan people did not idealise seclusion, the age of marriage was 17 in 1930 (much later than north India), girls readily went to schools, and today may migrate to the Gulf for work and send remittances back home. Whereas in the rest of India, labour migration remains male-dominated.

20th Century South Asia

Ghazali, Rumi, Tusi and Davani (the most influential Islamic ethicists) maintained that husbands gained ethical refinement by keeping their veiled, secluded from strangers and subservient. Ruling dynasties championed these ideals, while Sufi missionaries and madrasas encouraged wider conversion. South Asian men’s honour became contingent on keeping women away from male non-relatives.

Vintage photos suggest that female seclusion continued to be idealised well into the 20th century. Care must be taken when interpreting this data, since photos are by no means representative. Back in the 1940s, cameras were extremely expensive. In an age before smart phones, ordinary people did not photograph their everyday lives.

Accordingly, it is necessary to triangulate with historical research, ethnographies, my own life history interviews and nationally representative data. Together, the evidence suggests strong ideals of gender segregation.

Many of these photos were taken by Margaret Bourke-White. In 1930 she became the first Western photographer permitted to enter the Soviet Union, and document industrialisation. She was also the world’s first female war correspondent (stationed in Moscow, Italy, North Africa and Korea). Bourke-White then travelled to South Asia, where she chronicled the violence of Partition, and photographed Gandhi just hours before his assassination. Google Arts and Culture has 44,000 photos by Bourke-White.

This 1947 photo by Bourke-White shows Karachi women travelling by jeep to the Mahatma Gandhi Gardens - reserved for ladies on the last Friday of each month.

The following photos are from Lahore, 1946. Streets are mostly male; some women are heavily veiled, to maintain modesty.

Interpretations of modesty vary. Some believe that women should remain at home. Others do venture out.

This 1947 photo of Sind Moslem College in Karachi shows a ‘teacher addressing Pakistani male students in freshman English class where the girls are seated behind purdah wall in order to preserve their modesty’.

In 1947, hundreds of Afridi tribesman gathered in Peshawar to hear a speech from George Cunningham, Governor of the Northwest Frontier Province.

Some women appear nonetheless curious!

These 1947 photos by Bourke-White shows two sets of women, behind a barrier, watching the first Jirge (tribal assembly) at a Moslem League meeting, in Peshawar.

Just like the men, they may have wanted to learn about political reforms.

The two photos below show Muslim female beggars. One is holding out a card with a message in Urdu, saying she is a

‘widow with two children and nobody to support her.

The laws of Islam prohibit women from speaking loudly’.

This may indicate deep religious conviction around modesty and shyness. She may also be trying to show that she is a good Muslim, deserving of benevolence.

This 1947 photo shows Muslim men and women boarding at train in New Delhi, en route to newly independent Pakistan.

This is a 1962 photo of a Pakistani mother and child.

Pakistan’s diversity

Google Arts and Culture also highlights Pakistan’s historical diversity.

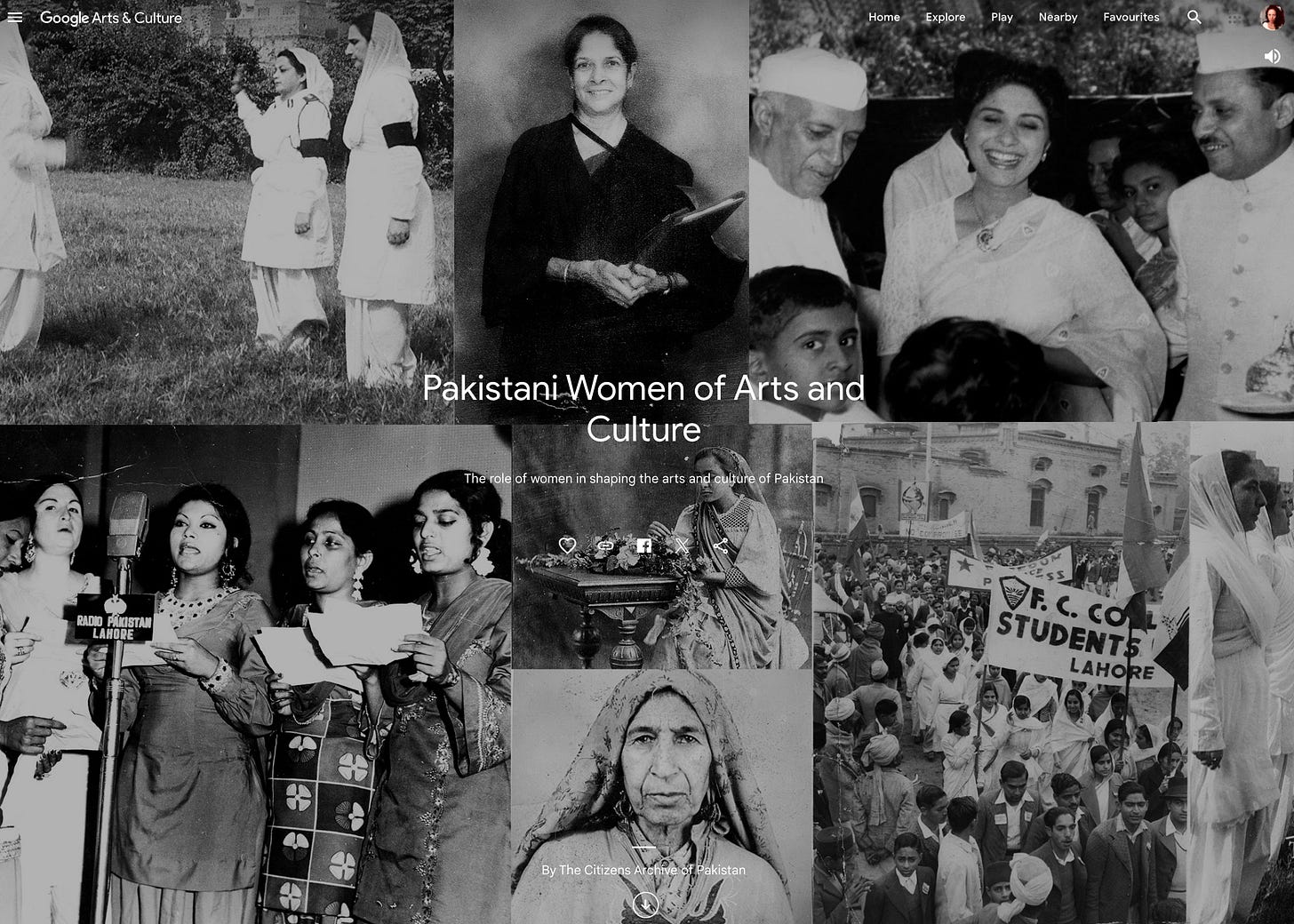

The Citizens Archive of Pakistan has created an excellent online exhibition entitled “Pakistani Women of Arts and Culture”. It features short biographies of Pakistani activists, artists, and writers, including their own voices and reflections.

Through further research, I have found photos of the Sind Muslim Women's National Guard during marching practice. 1947, Karachi.

The Sind Muslim Women's National Guard also practised combat with bamboo lathi sticks (traditionally used by the Indian police), 1947, Karachi

Farooq Jehan Taimuri was the first full time female employee of Radio Pakistan, in 1958. This appears to have been newsworthy. The reporter even puts ‘lady’ in inverted commas for additional emphasis.

Pakistani film actress Shamim Ara joined Farooq Jehan Taimuri to present a radio program for the Pakistan Army during the 1965 war.

Shamim Ara was a hugely popular film actress, producer and director.

Noor Jehan was a famous Pakistani singer and actress. She sang in Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi and Sindhi.

Kanwal Naseer (born in Lahore in 1948) was the first female telecaster of Pakistan. She made the first announcement on Pakistani television in 1964.

Attention, Coders!

AI might interpret photographs of exceptional women activists, writers and actresses as evidence of growing liberalism. But - in a country of 236 million people - this would omit subnational heterogeneity. The Khyber Pass remained extremely conservative - as shown in this image from 1980.

This year, in nearby Kohistan (home to 800,000 people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), clerics decreed it un-Islamic for women to participate in electoral campaigns.

Religious Authoritarianism & Saudi-funding

In 1977, Zia-ul-Haq launched a military coup and imposed religious authoritarianism. He strengthened religious laws, institutions and madrasahs. “Chador aur Chardevari” (the Urdu saying that women should be veiled and confined within the confines of home) became the slogan of the military regime. Women on television were obliged to veil. This continued under Nawaz’s government, until 1993.

Saudi funding and labour migration has encouraged growing Wahhabism. Many cinemas have been burnt down. Over the last 30 years, 846 popular cinemas have been demolished.

Across Pakistan, women report major restrictions. Only 30% of female respondents to the 2013 Labor Skills Survey said they could go to local markets or health clinics alone. One fifth of women reportedly never go to the local market. Women who are not allowed to venture outside the home are also much less likely to work.

Female labour force participation remains well below the global average. In Punjab, women rarely work outside agriculture. The overwhelming majority of Punjabis are also strongly opposed to female leaders, and in some villages there are restrictions on female voting.

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” (My Body, My Choice)

For a truly exhaustive analysis of cultural evolution, we need to supplement Google Arts and Culture with Instagram.

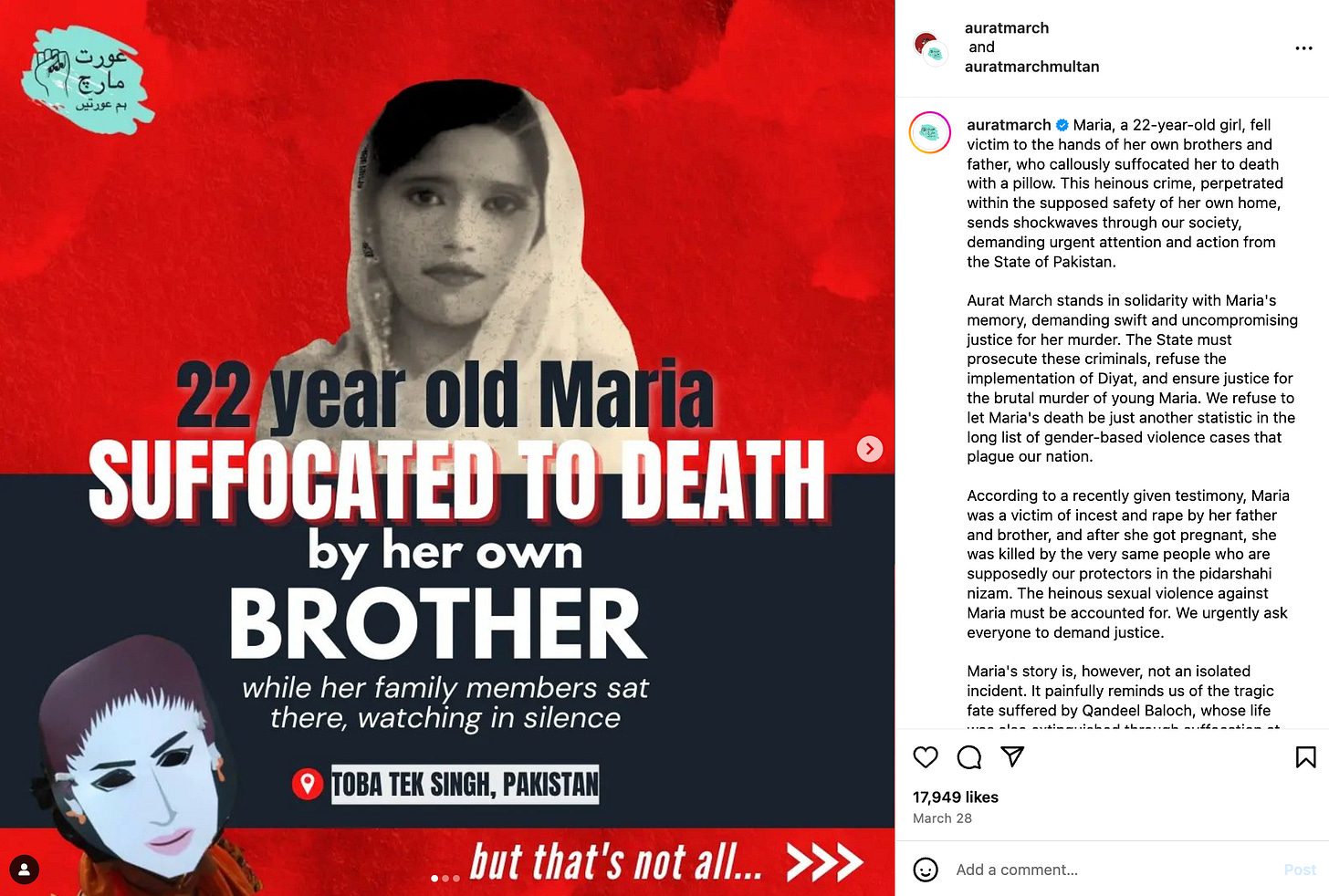

Since 2018, activists in Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore, Multan, Peshawar and Quetta have organised an annual “Aurat March” on International Women's Day. Their slogan is

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” (My Body, My Choice).

Google Arts & Culture does not actually stock these images, but one can follow their accounts and hashtags on social media, while also attending to backlash.

For context, we can triangulate with nationally representative data.

46% of married Pakistani women say wife-beating can be justified. Women respondents are more likely to endorse wife-beating if they are over-heard - indicating social policing.

Geography and Cultural Evolution

The Kalash people (in northern Pakistan) provide a great illustration of how geography mediates cultural evolution. The Kalash are polytheistic (not Muslim), and women continue to move freely.

“Our women are free” (homa istrizia azat asan)

Mountainous terrain may have been protective. This is consistent with Nathan Nunn and Diego Puga’s paper “Ruggedness: The Blessing of Bad Geography in Africa”. Rugged terrain shielded African communities from slave raids, and may have contributed to economic development. The same holds for culture. In places where the nearby force is patriarchal and technology is limited, then rugged geography is protective.

Can someone clever train AI on Google Arts & Culture?

Google Arts and Culture is a phenomenal new resource. Anyone with a smartphone can browse thousands of historical figurines, sculptures, paintings and photos from the past back five millennia. Going forwards, I will repeat this same process for every society in the world, and thereby trace the cultural evolution of gender.

Now, I have a question for my brilliant readers!

Could someone clever build software that traces millennia of social change, using Google Arts and Culture? Images are clearly tricky to code. For example, it was salient to me that Mughal women were shown on an upper floor, and that the Mughal-era Durga is very gentle. We also need to recognise that vintage photos are not necessarily representative, so care must be taken with interpretation.

Carefully coding Big Data, tracing cultural evolution over millennia, could be enormously revealing - as I have shown here. Military conquest, imperial expansion and religious institutions led to the glorification of purdah. Where men’s honour depends on female seclusion, gender inequalities are extremely persistent.

Research Idea!

Check out this gypsum statue of a woman from 2400 BC (what is now Iraq). She is not unusual. Similar statues of women wearing shoulderless dresses have been excavated, , from the same place and period. Elite women made temple donations and commissioned representations of themselves (unveiled). This is consistent with a wealth of archaeological evidence that Sumerian women initially acted as scribes, ran taverns, and were prominent in the public sphere. All together, it seems that Mesopotamians did not always idealise seclusion. That came later.

But when? And why? Could someone clever use Big Data to figure it out?

Related Posts

What Catalysed Imperial Expansion & Female Seclusion in Assyria?

“The Patriarchal Political Order” by Sole Prillaman (Review).

Further Reading

“Gendered Morality” by Zahra Ayubi.

“Women and Society in Early Medieval India”Re-interpreting Epigraphs” Anjali Verma

“The Masnavi, Book Five, by Jalal al-Din Rumi, translated by Jawid Mojaddedi.

“A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity” by Michael Cook (out in May 2024)

‘Women’s Autonomy in India and Pakistan: The Influence of Religion and Region’ by Jejeebhoy and Sathar

‘The Women's Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy” by Ayesha Khan

“Navigating Gendered Space: the Social Construction of Labour Markets in Pakistan” by Misbah Khatana

There is no society where a man's honor depends, not on his ability to avenge any insult offered to him, but on keeping his wife secluded. Thus if you observe that a particular man is ill treated by all and beaten, robbed or raped with impunity by those of vicious disposition, you are able to conclude that he is of low status. He is not considered an honorable man. His wife may be secluded but this does not affect his own status.

The correct question to ask is what incentive an honorable man- i.e. one whom none robs or rapes with impunity- might have to impose purdah on his womenfolk. This is social, political, and can change as productivity or a relevant opportunity cost ratio (i.e. comparative advantage) changes. When speaking of large swathes of territory over long lengths of time, you are likely to find a range of evolutionary stable strategies- e.g. pure pastoralist women have no seclusion while it increases as you approach urban centers. Here, what is relevant is reproductive success. Normally, this should favor sedentary, secluded, baby making machines but not always. In a period of 'folk-wandering', the tribes whose women fight may gain superior access to resources. Moreover, 'broken septs' would yield 'baby making machines' for the new overlords. What is interesting is that the 'Amazons' of such conquering tribes might find it in their interest to take the veil as Buddhist or Christian nuns and work for the creation and maintenance of a caste system based on degree of miscegenation. This phenomenon can also be found in Islam which has no monasticism.

Pakistan is interesting in that educated women were great supporters of Jinnah and some women- including a Jewish convert- gained a degree of political power. Was it inevitable this would be reversed? Suppose Pakistan had suffered the same economic crisis as Ershad's Bangladesh and had to do privatization and permit large factory dormitories for rural girls to supply the textile sector- could that have altered the current picture? What is certain is that all countries in the region have to raise the participation rate one way or another. But this can be done by replacing purdah with hijab.

> Before modern medicine, maternity was incredibly dangerous yet nonetheless necessary for group survival.

Doctors made childbirth dangerous, resulting in the poor (who couldn't afford them and used midwives) to have a lower rate of maternal mortality.

https://westhunt.wordpress.com/2013/06/07/the-breeders-equation/#comment-14508