“The Patriarchal Political Order” by Sole Prillaman (Review).

Do Self-Help Groups advance Gender Equality?

“How do we meaningfully improve women’s agency? I suggest the answer lies in fostering sustained and solidaristic collective action among women” - Soledad Artiz Prillaman.

In Madhya Pradesh, women vote but rarely attend village meetings. Men have greater greater political autonomy, political knowledge, collective efficacy, and social networks. Self-Help Groups and gender trainings are disruptive, however. By meeting regularly to manage small loans, rural Indian women build solidarity. They come to recognise shared grievances and collectively assert their priorities. That’s my crude encapsulation of Soledad Artiz Prillaman’s excellent new book, “The Patriarchal Political Order”.

Soledad Artiz Prillaman’s analysis draws on qualitative and quantitative research with over 9000 men and women in India. I accept the veracity of all her data, but remain extremely sceptical of Self-Help Groups and gender trainings. Without job-creating growth or cultural acceptance of divorce, rural women remain beholden to male guardians, trapped in casteist villages, seen as low-status - ever vulnerable to patriarchal backlash.

In short, Prillaman suggests that “women’s collective action is a successful response to male power and coercion, even without a priori structural change”. Meanwhile, I maintain the exact opposite.

Let me present Prillaman’s data, so you can decide!

“The Patriarchal Political Order” begins with several conundrums:

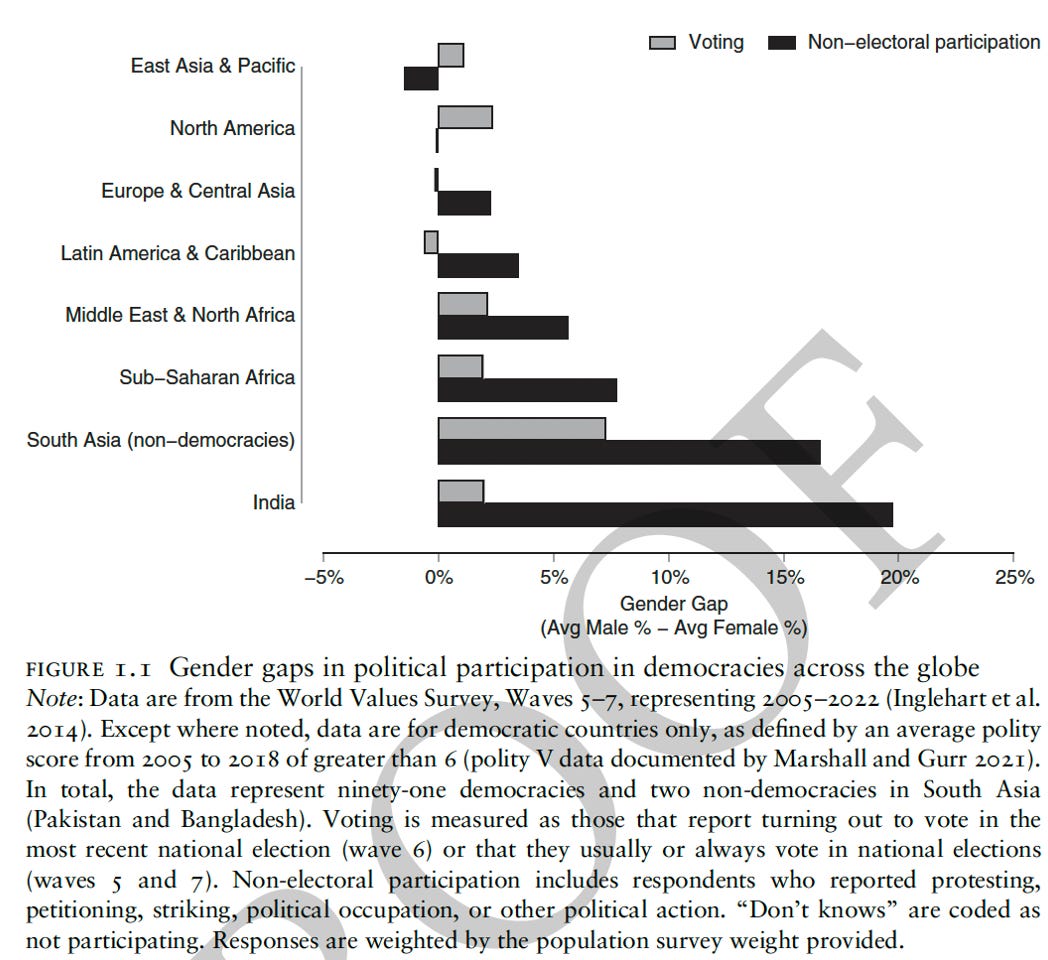

How come Indian women vote, but rarely engage politically?

Why do so few Indian women contact their representatives or voice their concerns in village meetings?

What might close this gender gap in political participation?

To learn more, Soledad Artiz Prillaman ran several large surveys and facilitated qualitative interviews across rural Madhya Pradesh.

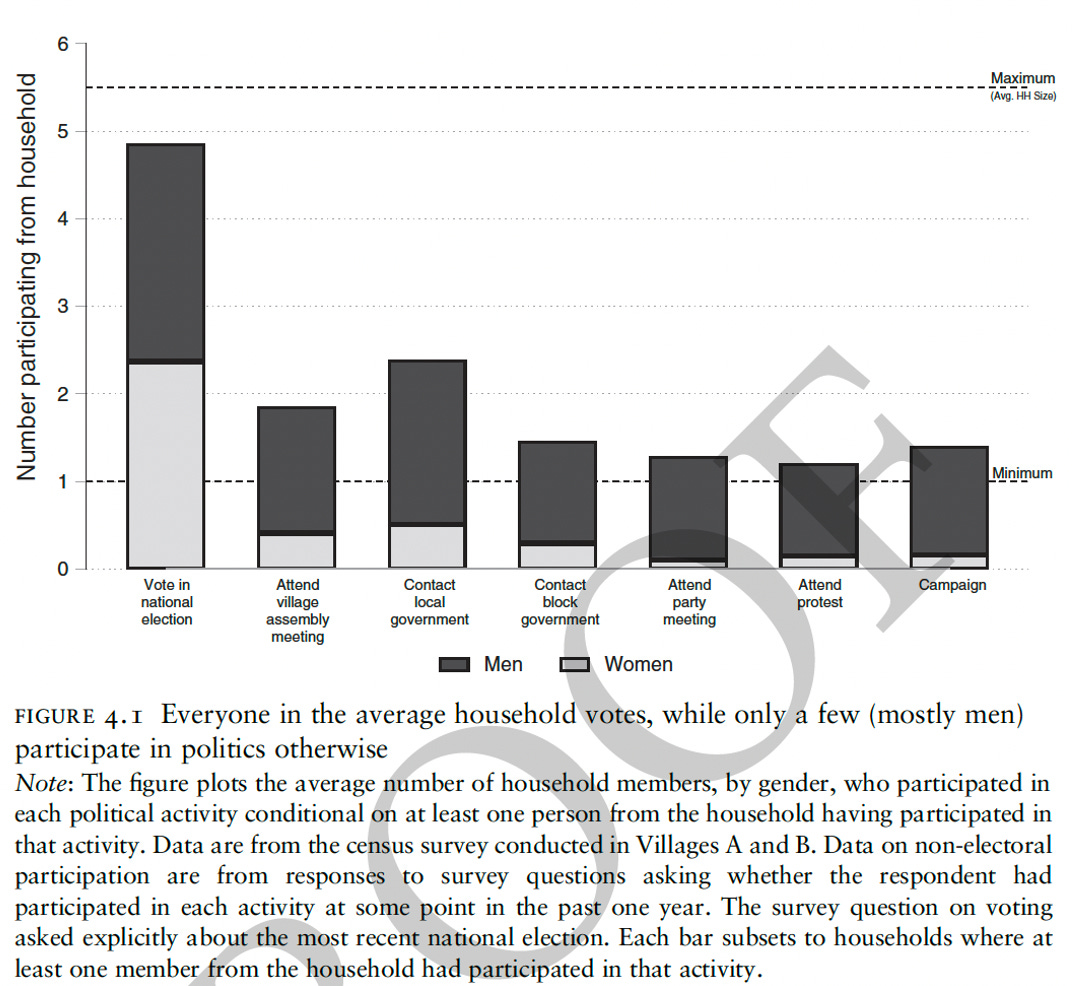

Women vote, but rarely attend meetings or make claims

Only 20% of women (but 68% of men) in Madhya Pradesh had attended a village assembly meeting in the past year. Only 16% of women (but 53% of men) had recently made a claim on a Panchayat official.

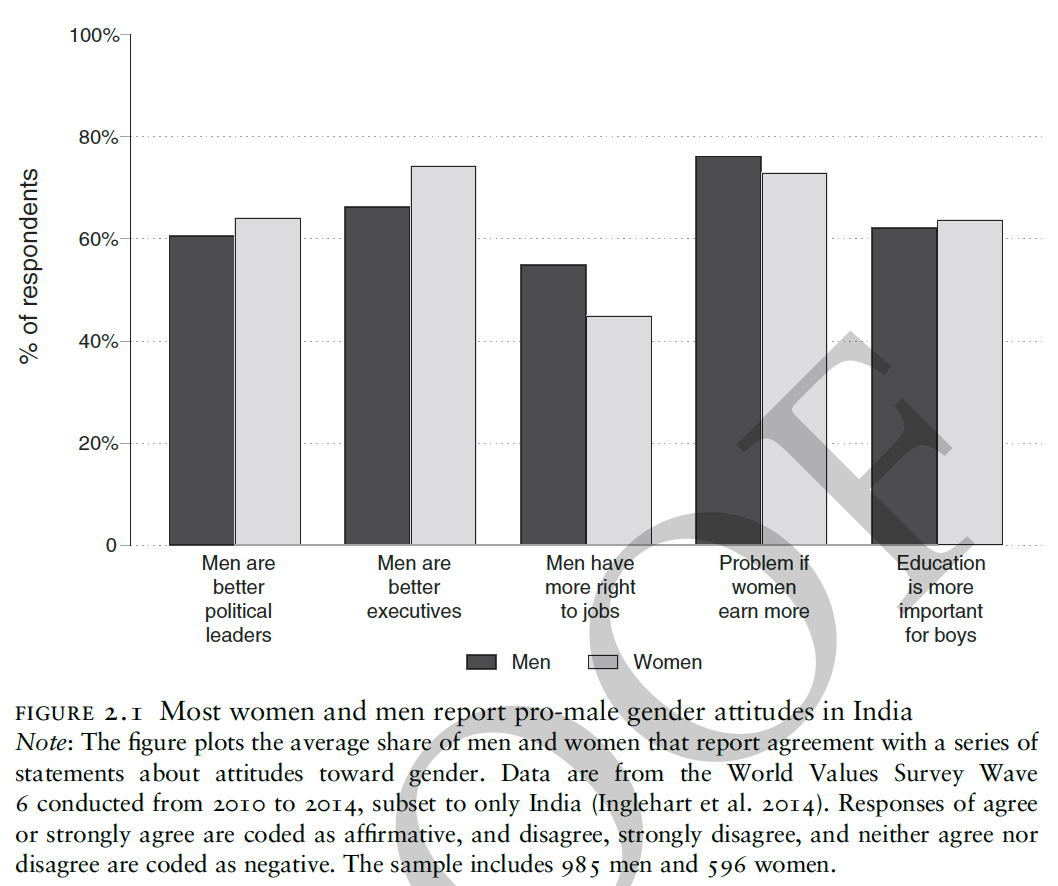

Survey data proves the accuracy of her book title, the ‘patriarchal political order’:

“78% of the variation in men’s and women’s political participation is unexplained by differences in educational attainment, labor market participation, income, land ownership, and free time”.

Why do people aspire to patriarchal ideals?

“The highest social status is bestowed upon households with high-earning men who can provide for their family without help from women and secluded women who remain in the household and are therefore pure.

The ideal woman does not work, cares for the household and children, does not interact with other men except with the permission or presence of men from her household, defers to the authority of her husband and male elders, and elevates household needs above her own.

In striving for this ideal, women often have restricted mobility within the community and access to independent networks outside the household except insofar as they serve the household’s needs… 86% of rural women report that they must ask permission to travel a short distance by train or bus, and only 50% stated that they would be able to do so alone..

Social status is conferred on those who conform to these roles, and role violations are socially sanctioned” (Prillaman 2023).

Superbly put. This is amply supported by evidence.

Most Indian men and women believe that men make better political leaders and business executives, and are more entitled to jobs and education.

Caste categories and age groups make little difference to gender attitudes.

Why do patriarchs let women vote?

In Madhya Pradesh, husbands and fathers-in-law often direct women’s votes. Female voting serves their interests.

For Kamla Bai, “I will accept whatever my husband will say”.

Why do so few women attend meetings or make political claims?

“No one will listen to them”, remarked Pushpa.

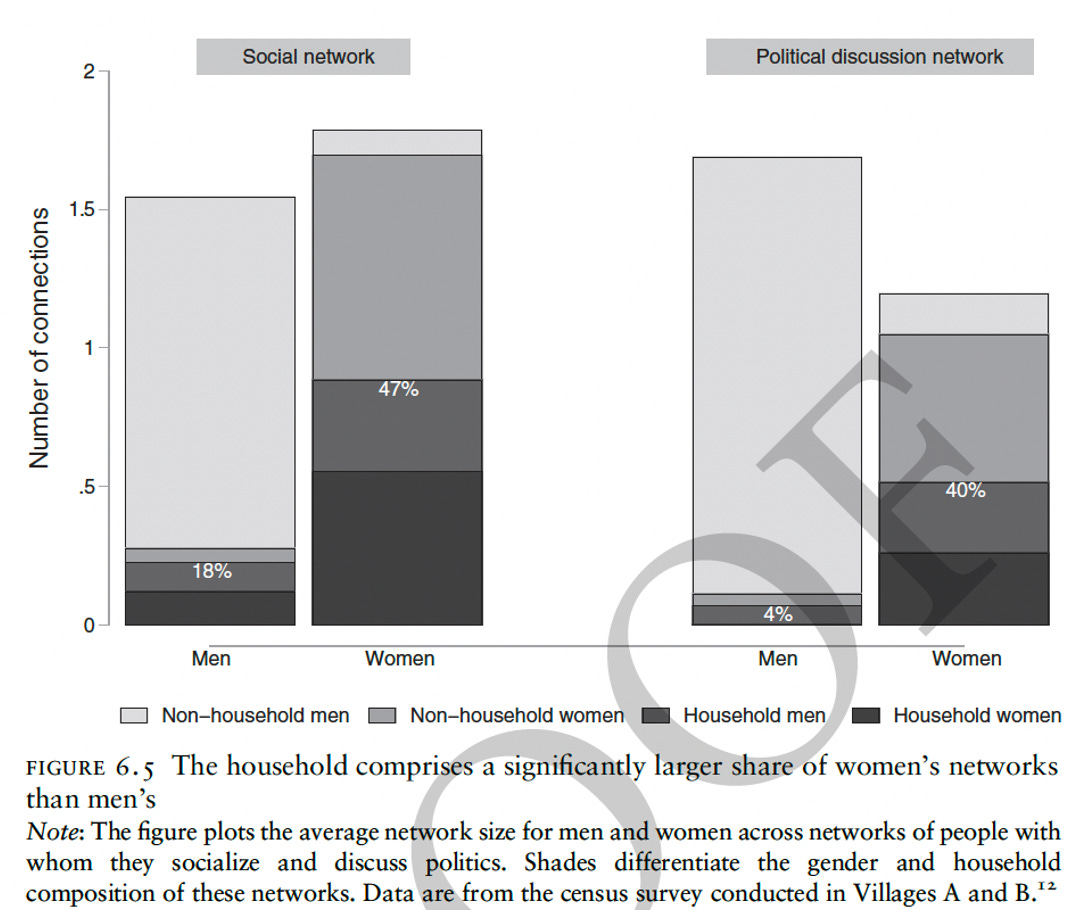

Women are much more likely to engage in non-electoral politics if they discuss politics outside their households, yet this is uncommon. They have far fewer political connections.

So even though women have different political priorities (caring more about water and toilets), they rarely apply political pressure.

Men’s political networks are larger, varied & more influential

Men discuss politics with a vast range of unrelated men - some of whom are politically influential. As a result, they become much more knowledgeable.

Women, meanwhile, are much more rooted in their families, or else mingling with other similarly marginalised women.

Do Self-Help Groups Advance Gender Equality?

Prillaman compares villages with and without SHGs (‘matched pairs’), as well as well as women who have similar characteristics but differ in terms of participation.

SHGs promote women’s solidarity, political knowledge and participation

Financial incentives are the main reason women join SHGs, but their effects are actually much more social. By gathering together over many years, sharing grievances, and resolving problems, women realise commonalities and build solidarity - argues Prillaman.

One was abused by her husband and blamed herself. SHG meetings broke the silence; she realised male violence is widespread.

They forged a sisterhood:

“We are ten women. We are like friends to each other. We are like friends or sisters to each other. If anyone of us has any problems and she alone cannot solve it, then all of us try to solve it. When all of us come together, then it becomes easy.”

In treated villages, women were more likely to say they knew the names of political leaders, how to make political claims, and various bureaucratic details. They were also more likely to say they’d be confident to speak up at village assembly meetings.

Women whose groups had petitioned the Panchayat were much more likely to attend village assembly meetings. They gained solidarity and strength in numbers.

Patriarchal beliefs persist

SHGs do not seem to shift attitudes about male breadwinners or men’s superiority as leaders.

For me, that’s not surprising. These are village women discussing their daily struggles. Why would they suddenly champion female economic independence? That’s not something one can readily observe in rural Madhya Pradesh.

Now we see the real power of the SHG: not changing beliefs, but building solidarity.

SHGs do not improve food or income security

Does Gender Sensitisation Advance Gender Equality?

Prillaman evaluates the impact of participatory gender sensitisation, facilitated by a feminist NGO facilitated sessions, across four Indian states from 2011 to 2015, sponsored by UN-Women.

Gender trainings explored the roots of gender norms, women’s livelihood opportunities, political processes and gender-based violence.

Sessions were designed to raise awareness, encourage discussions, build solidarity and catalyse activism.

Gender Sensitisation amplified Political Participation

SHG women in treated villages were indeed more likely to exhibit political knowledge, express efficacy and participate politically.

Gender-sensitised women are no more likely to endorse gender equality

(Loyal readers may recall my discussion of gender sensitisation in Egypt. Null effects).

(Devoted aficionados will know my paper on gender sensitisation in Zambia)

Gender-sensitised SHG women are more likely to be publicly humiliated by their husbands

This is clear evidence of patriarchal backlash.

Husbands sought to assert their superiority and belittle their wives.

Patriarchal backlash is not unique to rural Madhya Pradesh. As Prillaman documents, Indian feminist activism often triggers violent retaliation.

Sole Prillaman must be lavished with praise for being so incredibly thorough in her qualitative and quantitative analysis. Her book is an empirical treasure trove! BRAVO.

Can SHGs and Gender Sensitisation Substantially Advance Gender Equality?

Here’s where Prillaman and I differ:

Prillaman thinks that even if there are no structural changes, SHGs and gender sensitisation can still promote collective mobilisation. Patriarchal backlash is an inevitable part of the process, culminating in greater gender equality:

“small tweaks to the design of participatory programs… can yield even larger gains to women’s political inclusion and open up the **necessarily conflictual** process of norm renegotiation [emphasis added]

The renegotiation of power and voice is thus likely to be a circular process, in which forward motion is met by friction”.

Here’s how I see it.

Men in rural Madhya Pradesh believe they are knowledgeable authorities, deserving of deference, entitled to respect. Failure to achieve these ideals is socially humiliating. Women, meanwhile, are seen as having lower status. Their role is to serve men.

Prillaman predicts that marginalised women can advance gender equality just through mobilisation, but why haven’t we seen more evidence of social change in SHG-heavy rural India?

While SHG women are now permitted together in public, that seems to be men’s upper limit. Women remain economically dependent on patriarchal providers, enmeshed in casteist networks which demand strict conformity.

Given the persistence of status beliefs, female power grabs will seem illegitimate. Challenging the patriarchal order provokes violent backlash. Considering women’s lack of economic autonomy, rarity of help-seeking, and police disregard, one might be extremely cautious about triggering male anger.

My global history of gender suggests that feminist activism is much more successful when accompanied by job-creating economic growth.

Through paid work in the public sphere, masses of women demonstrate their equal competence in socially valued domains, become recognised as knowledgeable authorities, form new friendships, build diverse networks, expand their horizons, and ultimately gain status. That’s precisely what happened in Singapore.

Prosperity also breeds liberal tolerance. People who experience upward mobility tend to believe we can all thrive. Contrast liberalising Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan with much poorer, more religious, more patriarchal Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Once women gain equal status and men become more liberal, then feminist activism massively advances gender equality. But all these processes must come together.

The Patriarchal Political Order

I strongly recommend Soledad Artiz Prillaman’s tremendous book, “The Patriarchal Political Order”. She provides a veritable feast of qual and quant data. BRAVO!

To close, here are some beautiful paintings by Malvika Raj. She’s a Dalit artist from Patna (Bihar). And it was in rural Bihar where I did my own research on SHGs.

The financial backing is coming from global central banks… https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/