Who are the world's most influential philosophers?

Ghazali, Tusi, Rūmī and Dawānī are among the most influential philosophers in the world, yet curiously unknown in the West. These Islamic ethicists were patronised by Seljuk, Ottoman, Timurid, Safavid and Mughal rulers, who institionalised their ideals. Across their vast empires in Anatolia, North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia, men’s honour became contingent on female seclusion. Imperial expansion thus propounded patriarchal religions, thereby entrenching gender inequality.

This essay explores Ghazali, Tusi, Rūmī and Dawānī’s global influence and moral philosophies.

Warning: it also includes violent bestial sex.

Ghazali, Tusi, Rūmī and Dawānī were all patronised by powerful empires

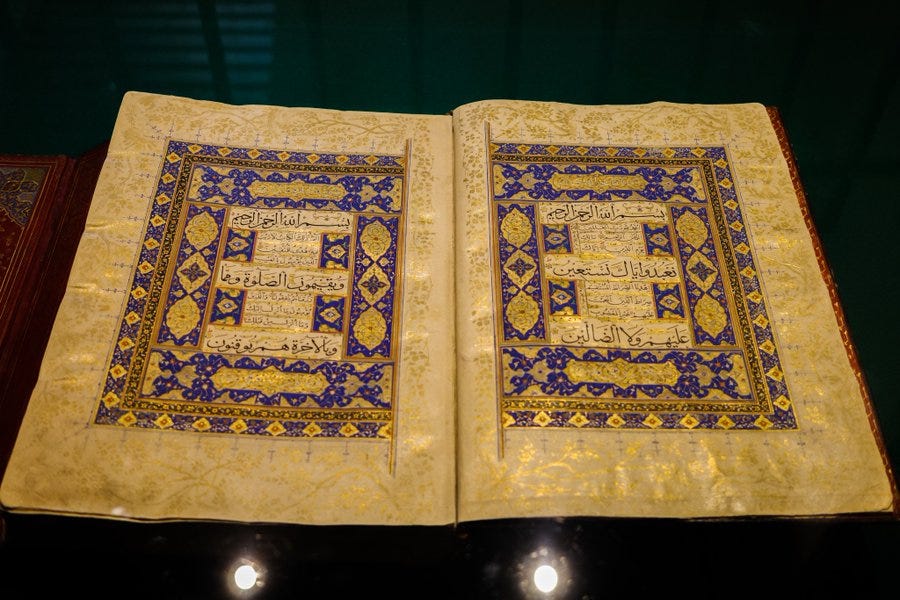

Tusi’s Akhlâq-e Nâṣeri (13th century) entered South Asia with the Timurids, and became a favourite reading of the Mughal political elites. Mughal Emperor Akbar further instructed his officials to read both Tusi and Rumi. By the 17th century, Tusi’s Akhlâq was part of the Mughal madrasa syllabi.

Rumi’s Masnavi (13th century) is the Sufis’ most influential text. Seljuk, Ottoman, Timurid, Safavid and Mughal rulers all lavished him with praise. Emperor Akbar regularly recited Rumi’s Masnavi. Rumi continues to be widely revered. His ornate tomb in Konya attracts 1.5 million pilgrims a year.

Ghazali (12th century) was heralded as “Hujjat al-Islam” (authority on Islam, proof of Islam”. His moral and political philosophy was institutionalised by the Ottoman Empire. Translated into Turkish, it was frequently discussed, and commented upon. Ghazali's wisdom was heavily cited in policy advice to Ottoman rulers.

“If all other Islamic books disappeared, leaving only the Iḥyāʾ, it would be sufficient” - declared Turkish polymath Katib Çelebi in the late 17th century. He was referring to Ghazali.

Dissent was repressed. Books of Ghazali’s critics (like Ibn Rushd) could not be found in the Şehid Ali Paşa Library. Mehmed Şemseddin (1883–1961), a professor of history and Islamic studies, argued that Muslim philosophy was “gravely punched by merciless and effective strokes of al-Ghazālī”. Ottoman scholars had to toe the line.

Heterodox Muslims should be culled, said Ghazali. As Timur Kuran explains,

‘Ghazali helped to establish the practice of treating heterodox Muslims as apostates who deserve execution. He urged the killing of independent philosophers as well as Ismaili Shiis, insisting that rulers and their military had a duty to destroy heretics… The fatwas of leading Islamic interpreters, such as Ghazali… were collected in volumes for use by later interpreters… statesmen and judges’.

Ghazali, Tusi, Rumi and Davani’s Islamic ethics were thus propagated across Anatolia, North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia. So what did they say about gender?

In brief,

Men are intellectually superior, and men alone cultivate ethical refinement

The ideal wife is pious, fertile and obedient

Men cultivate ethical refinement by keeping their wives subservient, veiled and secluded

But what about women’s earlier freedoms?

Wives organised the daily minutiae

Filial loyalty was revered as the highest piety

Marital love was discouraged

Male homosocial love was praised

“Justice requires that each one should stay in his rank”

Politics and public life were men’s domain

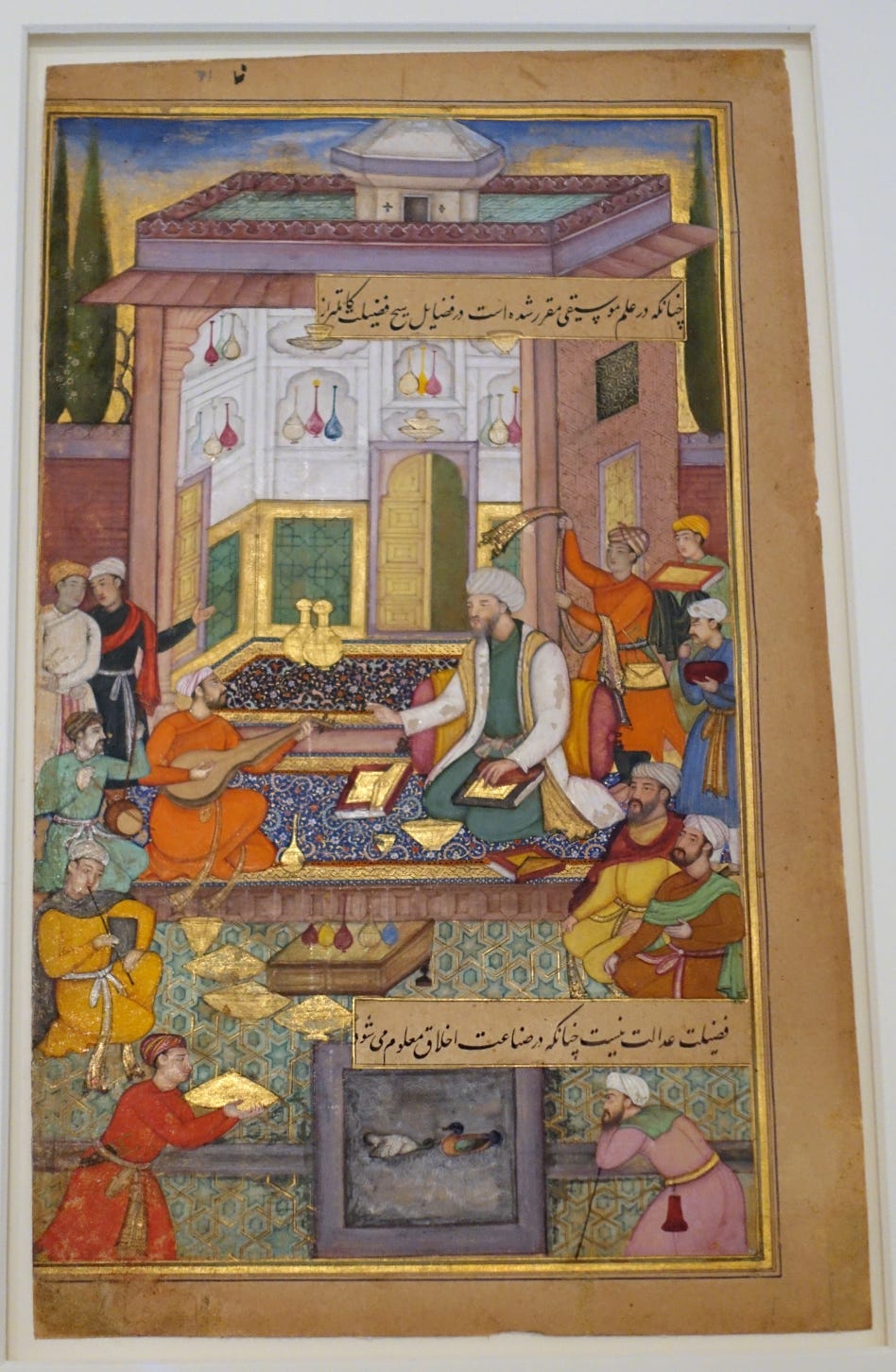

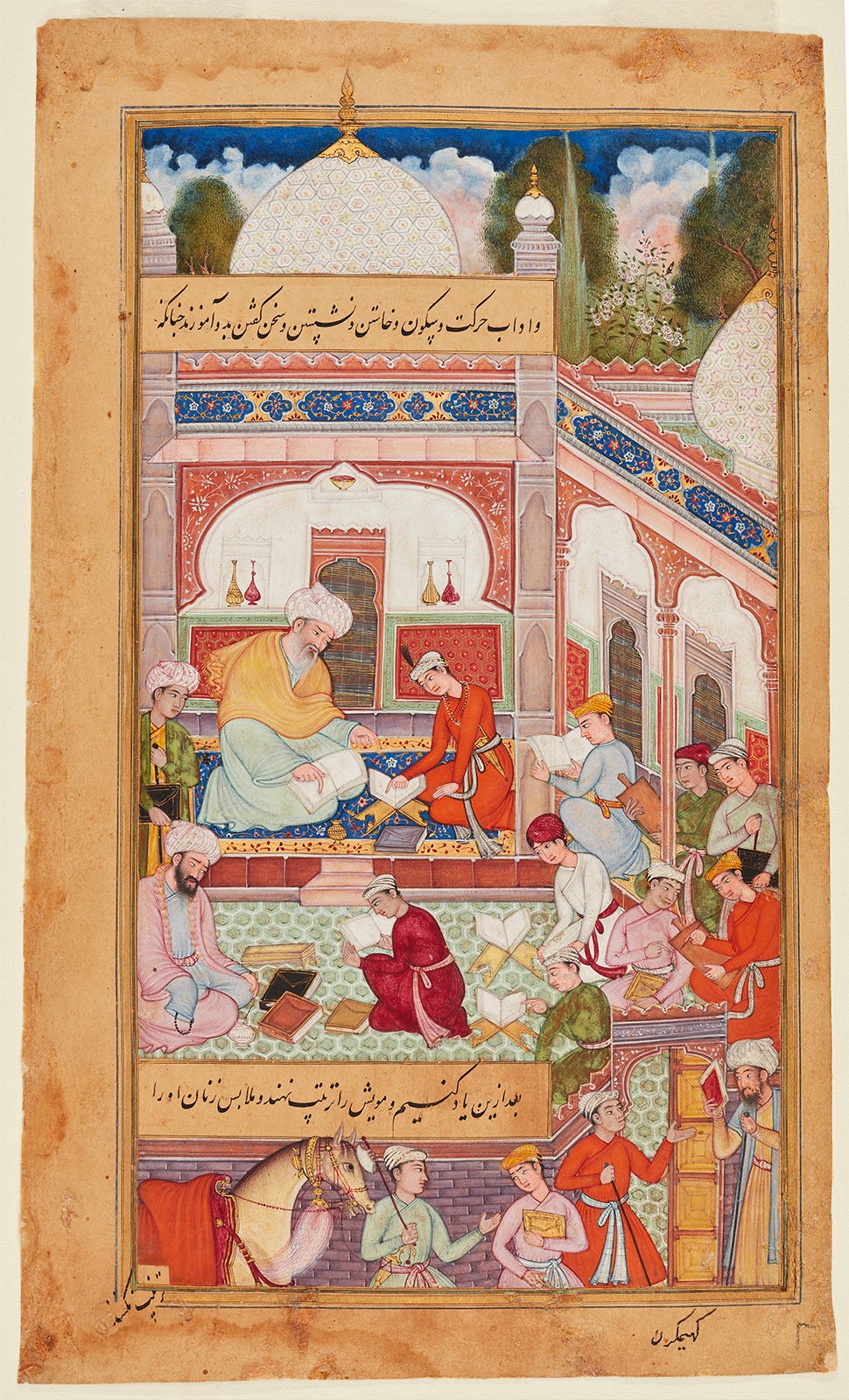

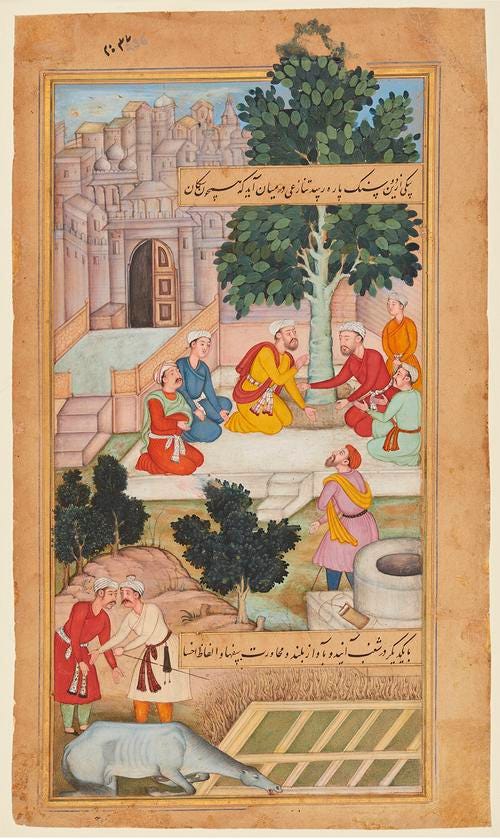

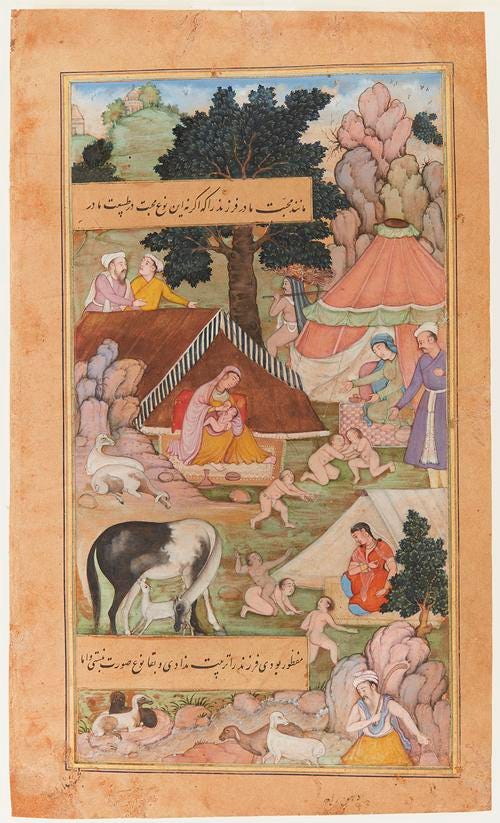

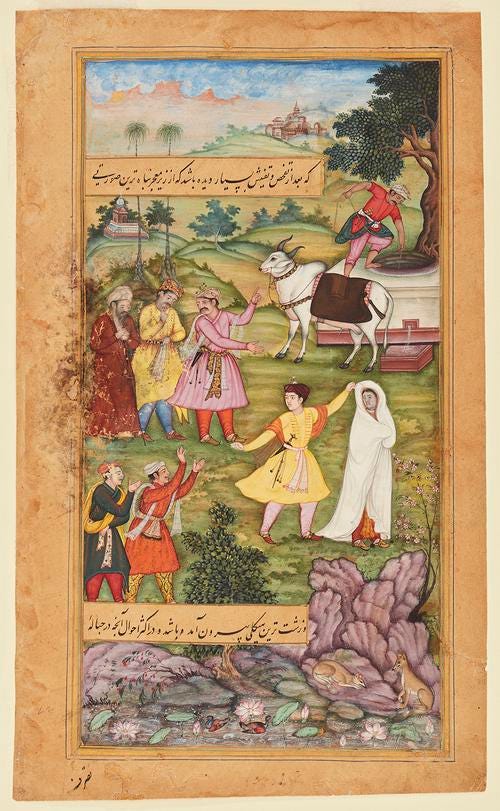

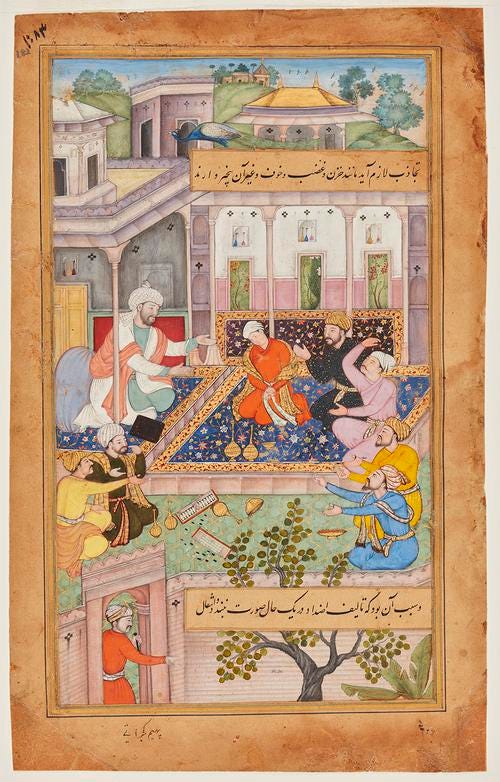

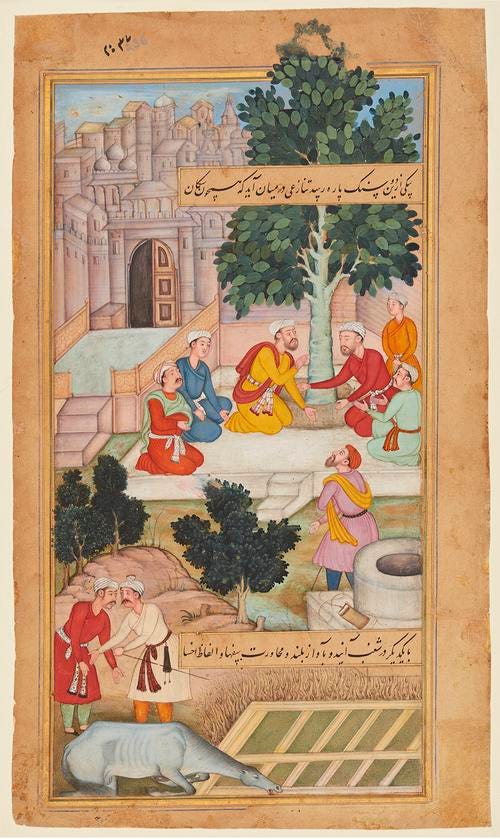

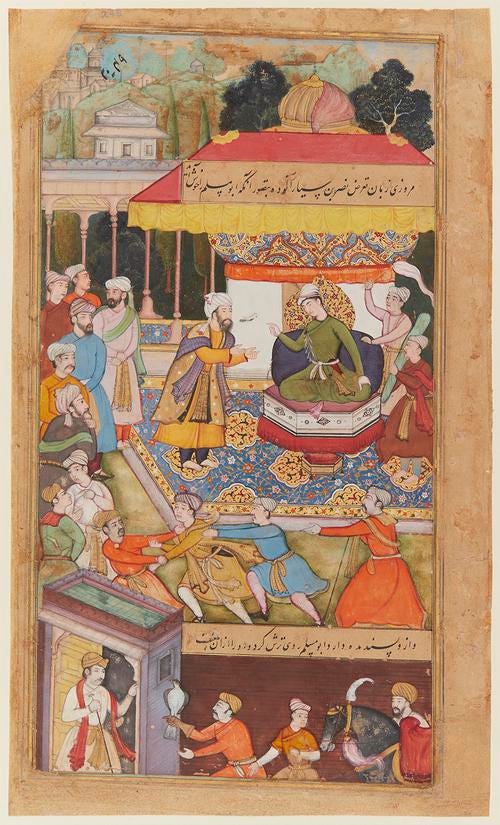

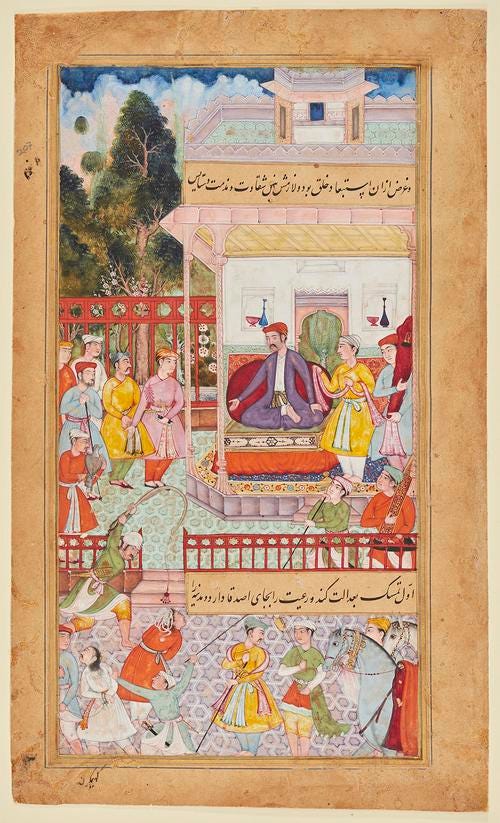

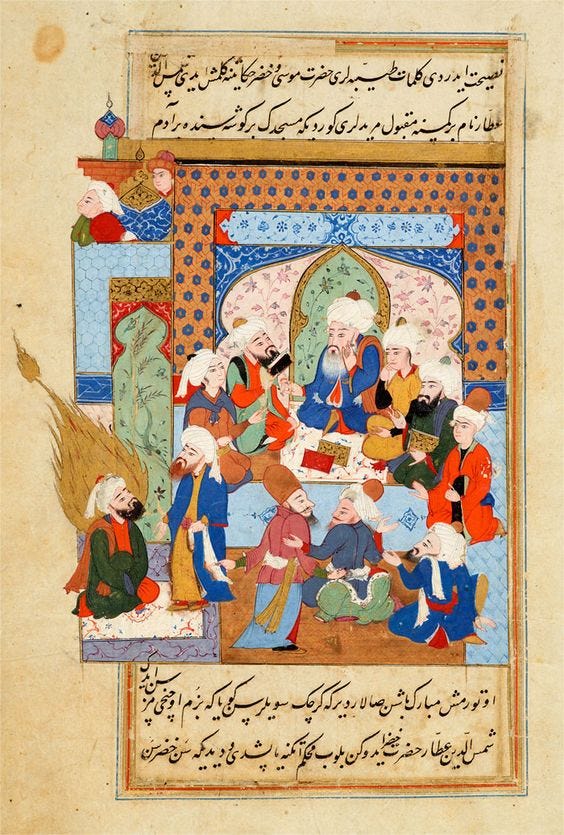

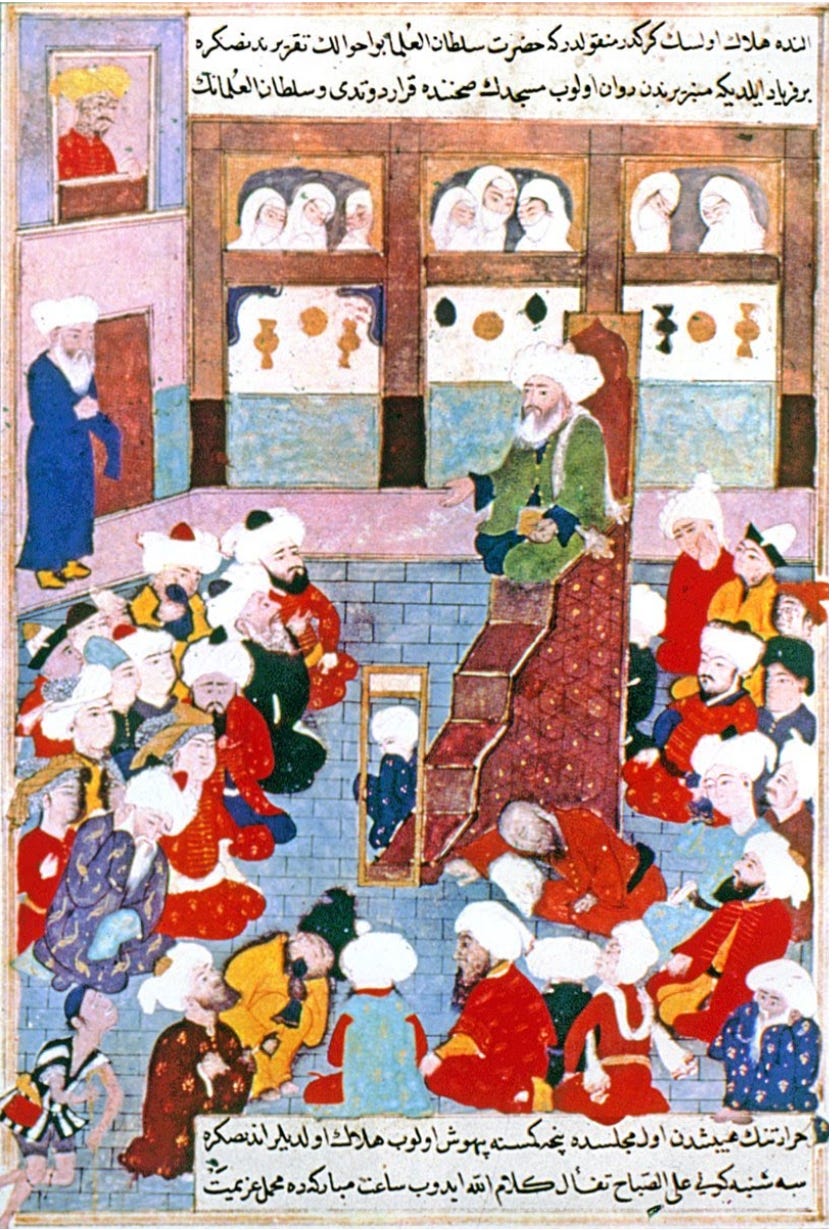

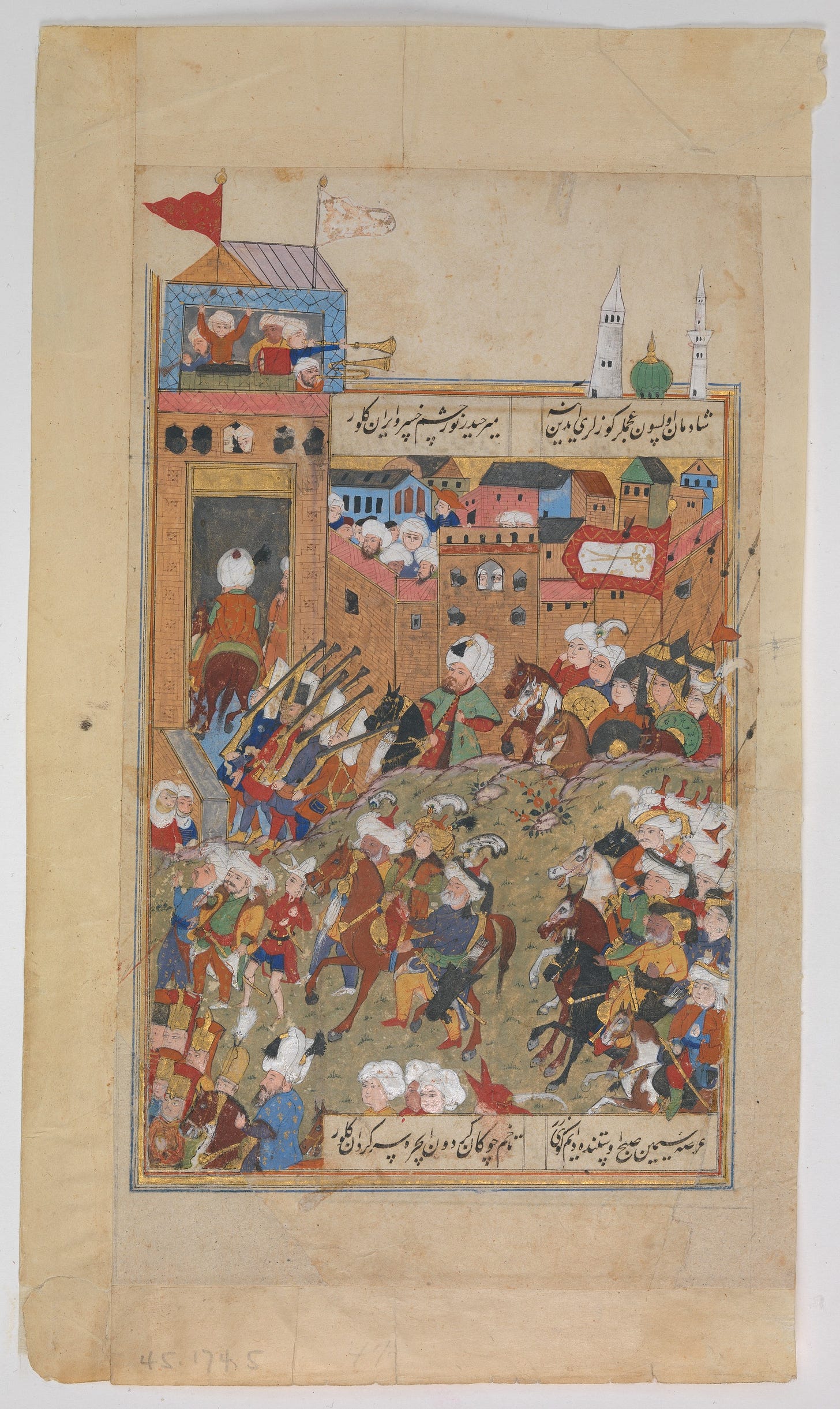

This essay draws heavily on Zahra Ayubi’s brilliant analysis of Ghazali, Tusi and Davani’s philosophies. I incorporate my reading of Rumi’s Masnavi Book 5, and interviews with leading Sufi sheikhs. Plus, I add colour paintings from Tusi’s ‘Akhlaq-i Nasiri’, commissioned for the Mughal Emperor Akbar. These illustrations shed light on how Tusi’s theology was embraced by Mughals.

Men are intellectually superior, and men alone cultivate ethical refinement

Ghazali, Tusi and Davani all thought women had souls, but were ‘overly emotional’ and ‘intellectually deficient’. Accordingly, explains Ayubi, they should be ruled by men.

Moral advice was directed at men, because they were seen as intellectually superior. Ayubi details that for Ghazali, Tusi and Davani, ethical refinement was for men alone.

Rumi similarly likened women to donkeys, “She shares that poor donkey’s assinity. Animal qualities prevail in them - they’re drawn to scent and colour in this realm” (Masnavi, Book 5: 2465-70). After likening women to donkeys, Rumi repeatedly reminds his male audience that if donkeys are seized or killed, one needn’t worry, since “you’re not a donkey” (ibid: 2540, 2550).

The ideal wife is pious, fertile and obedient

Piety, virginity, fertility, sexual submissiveness, and obedience were repeatedly emphasised by Ghazali, Tusi and Davani. Wives’ chief role was to reproduce.

“According to the ethicists, a wife should humble herself like a “little concubine” (Tusi uses the diminutive form of the term, kanizak)” - notes Ayubi.

They “recommend that a husband strategically show or withhold benevolence in order to coerce the wife into submission.”

In Mughal Emperor Akbar’s copy of Tusi’s Akhlâq, there are only two pictures of women. ‘Motherly love’ is glorified in the illustration below.

Men cultivate ethical refinement by keeping their wives subservient, veiled and secluded

“For Tusi, the wife’s appearance in public is inextricable from the husband’s masculinity”, explains Ayubi.

“The ethicists state that a husband should undertake great endeavors to keep his wife in satr va hijab (curtain and veil) and away from ghayr mahram or na mahram (nonkinsmen) in order to shield her from people who might tempt her, and vice versa.

The man should prevent his wife from meeting male strangers, carrying on with strange men through window peepholes or on rooftops, attending superfluous social gatherings, and even talking to older women who no longer veil and who recount stories about the local social scene”.

Satan is searching for ways to corrupt men, and draw them away from God. He rejoiced when he discovered the most powerful trap: a woman’s beauty - explained Rumi (Masnavi, Book 5, 940-960). But carnal pleasures are only temporary, and their pursuit always results in abject humiliation:

“Nothing's worse than lust for you.

It has disgraced so many reputations,

Made fools of millions of intelligent ones (Masnavi, Book 5, 1370-1375)

Rumi gives multiple warning stories - including the woman who desired a donkey.

“The donkey’s penis grew erect and stiffer

It thrust in her and spread a fire within her.

The well-trained donkey pushed in all the way

Up to its balls and she died straight away.

The penis in her made her liver tear;

Her intestines were also torn in there.

And she said nothing—on the spot she died.

The chair fell one side, she the other side.

The room was soaked in blood. What a bad state!

The woman fell down dead: unfortunate fate.

A bad death with so much disgrace, O father:

She was a donkey’s penis’s frail martyr!

Heed the Qur’an: ‘The torment of disgrace.’

Don’t lose your life through such a fall from grace.

The donkey is the carnal soul: to be

Under it is more shameful obviously:

If you die for the carnal soul, be sure

You’re like this woman who was so impure”.

On the Day of Judgement, extra-marital sex will be punished. “Don’t lose your life through such a fall from grace”, “Don’t quit the weighing scales.. because of greed. Both lust and greed are foes that will mislead (ibid: 1394). To prevent sin, Rumi emphasises that one must impose restraints on the metaphorical donkey (ie. the thing that attracts you). He endorsed tent-like veiling (ibid: 3295).

Men are presented as intellectually superior, but nonetheless prone to Satanic temptations. Men’s libido is ‘vulnerable and frail’ (ibid:2465). Tusi similarly encouraged men to protect their womenfolk from other men’s lust.

By repeatedly emphasising men’s inability to control their sexual urges, Rumi may have cultivated distrust of other men, perpetuated anxiety over one’s womenfolk, and encouraged cloistering. It sharply contrasts with 17th century Sweden, which embraced nude mixed gender saunas.

But what about women’s earlier freedoms?

Islamic feminists note that the Prophet’s first wife (Khadijah bint Khuwaylid) was a successful trader. Nevin Reda insists that at the time of the Prophet, women had full access to major mosques and prayed next to men, without any barriers nor separate entrances.

But as Ayubi explains, Ghazali insisted that female seclusion was necessary to restore proper piety:

“Ghazali… quotes Umar ibn al-Khattab, who said that the Prophet allowed women to go into public back in the days when they used to veil themselves properly, but that if he saw the ways of women today, he would rescind that permission.

Ghazali then states that “there is greater harm to women at public sites and gatherings” than in the past. Here, Ghazali echoes the common argument of the ‘ulama’ lamenting the loss of a golden era when women knew how to conduct themselves in public”.

Wives organised the daily minutiae

Ghazali, Tusi and Davani suggested that the wife could exercise domestic authority, such as over the household’s financial budget. But Ayubi suggests that men may have just been outsourcing ‘the daily minutiae: such as ensuring that children ate their supper, did their chores, and completed their lessons.”

Tusi still maintained wives must obey and handover any wealth.

This is an important insight about patriarchy. Today, some people downplay (or even deny) inequality by insisting that women exercise domestic authority. But, this is still compatible with an ideology where men are intellectual superiors, owed obedience, and are uniquely capable of spiritual refinement.

Moreover, as we will see, the public sphere was reserved for men.

Filial loyalty was revered as the highest piety

Honouring and obeying one’s parents were repeatedly extolled. Ghazali emphasises,

“doing good deeds for one’s mother and father is better than prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, and just struggle [ghaza].”

Marital love was discouraged

“The ethics of marriage have very little to do with love”, explains Ayubi.

“The ethicists’ scrupulous effort to describe for men how they ought to control their wives is rooted in their anxiety that men could be manipulated by the sentiment of love into losing their power to women”.

Ayubi details that for Tusi, “husbands should guard against showing excessive love, which could cause the wife to expect to dominate over her husband, a grave corruption”

“Tusi provides a list of those whom an ethical man should love, and his list also excludes women”.

This is crucial. As I have argued, romantic love is a major driver of gender equality, as it means mutual desire for each other’s happiness. Patrilineal societies tend to suffocate marital love, as it draws men away from their proper loyalties to kin and the male brotherhoods.

Sons’ over-riding obedience to their mothers - and lesser concern for their wives - also enables mothers in-law to be tyrannical, abusive and exploitative. If men are not encouraged, nor given opportunities, to form loving relationships with their wives, then they may not necessarily empathise with her wants or welfare, nor feel remorse about being violently abusive or controlling.

Male homosocial love was praised

Ayubi explains that Ghazali, Tusi and Davani repeatedly celebrated male homosocial love. Quoting several hadiths, Ghazali deemed male friendships more important than wives, because men were intellectual equals, who helped cultivate each other’s spiritual refinement.

This is a hugely important insight, and it is over-looked by most studies on gender. By socialising together, men build trust, friendships and loyalty. They come to respect and rely on each other’s advice. In trust-based societies, where government, commercial, and political networks, all rely on whom you know (‘wasta’ in Arabic, ‘aap kisko jante ho’ in Urdu), these fraternal ties help to consolidate men’s advantage.

Politics and public life were men’s domain

Court was to be a man’s world - insisted Ghazali, Tusi and Davani. As each of the illustrations of Akbar’s Akhlâq make clear, the public community is always male.

Religious rituals played a crucial role in strengthening feelings of unity, trust and social cohesion - argues Robin Dunbar. Congregational worship is repeatedly praised in the Quran and Hadith:

“The reward of the congregational prayer is twenty seven times greater” (than that of the prayer offered by a person alone) (Sahih al-Bukhari 649)

Muslim men are strongly encouraged to pray together, which may have reinforced bonds of brotherhood.

At the time of the Prophet, women may have had access to major mosques and prayed next to men. However, the Hadiths still imposed restrictions to prevent lusty temptations. Women’s admittance to the mosque was conditional on them not wearing perfume and being veiled. Furthermore, several Hadiths say it is more merit-worthy for women to pray at home, especially in that ‘discreet portion of the home’.

Over time, piety increasingly came to require gender segregation and mosques were reserved for men. This may have encouraged fraternal solidarity.

Across the Islamic world today, men are much more likely to attend religious services. Male-only religious rituals may have strengthened brotherly love and loyalty. In mosques where men alone listen to the Friday sermon (khutbah), men alone are receiving ethical advice, just as advised by the Persian theologians.

“Justice requires that each one should stay in his rank”

No matter someone’s intellect, they should stay in their rank. Social mobility was firmly rejected by the akhlaq texts, explains Ayubi. Tusi and Davani both stated that,

“Justice requires that each one should stay in his rank and not transgress that rank”.

This sharply contrasts with East Asian ideals of upward mobility. However, it is perfectly consistent with South Asia’s pre-existing caste system.

More gender equal religious minorities have been repressed

In Turkey today, Alevi Shiis (versus Sunni) men are much more likely to endorse gender equality, and Alevi women are much more likely to work. In Alevi ‘Semah’ rituals, women and men dance together (as shown below). This reflects greater liberalism, without strictures of female seclusion.

However, this more gender equal Muslim sect has been repeated persecuted - by the Ottoman Empire and contemporary Turkish Government, which still does not recognise their houses of worship. Without violent repression, this more gender equal sect could have achieved greater prominence and popularity.

In Pakistan, Ahmadis tend to be more progressive, but have been oppressed. In 1974, Pakistan’s parliament declared them to be non-Muslim. They are not allowed to proselytise or call their places of worship ‘mosques’. When applying for a national identification card, Pakistanis must call Ahmadis non-Muslims.

TLDR

Ghazali, Tusi, Rumi and Davani are some of the most influential philosophers in human history. Ottoman, Safavid, Timurid and Mughal emperors propounded their ideals of female seclusion.

It is this history of military conquest and imperial expansion, hitched to moral philosophies of male honour alongside fears of lust and sexual predation, that explains why female employment and political participation remain so low in South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa today.

Related posts:

Further Reading:

M. Sait Özervarlı (2015) "Ottoman Perceptions of al-Ghazālī’s Works" in "Islam and Rationality: The Impact of al-Ghazali Papers Collected on His 900th Anniversary"

“Gendered Morality” by Zahra Ayubi.

“The Masnavi, Book Five, by Jalal al-Din Rumi, translated by Jawid Mojaddedi.

That's a great overview.

One thing that I think is extremely relevant to why their thinking developed as it did. Tusi and Rumi were contemporaries, and were alive when the Mongol siege of Baghdad happened. Ghazali lived through the Crusades, as did they. It was an unstable time with intense conflict, which meant the incentive to seclude women was extremely powerful. They just provided the religious justification.

Excellent piece.

One interesting thing to consider is why the "patriarchal Muslims" only "won" after the Mongol conquests. Before that there was a significant tradition of Islamic heterodoxy that even went as far as pseudo-atheism at the extreme edges. Centralized extractive states would have logically found the latter a more useful ideology, but why did it so long for it to win? Early 13C Baghdad was reported to be "liberal" (in the historical context) on gender relations.

All these people are Persians. So it's perhaps more specifically a question of why these trends won in the Persianate world (and filtered down to the other Muslims).