Romantic Love is an Under-Rated Driver of Gender Equality

Patriarchy is reinforced by fraternal solidarity. The Athenian demos, German guilds, Tswana kgotla, Chinese imperial dynasties, Muslim Brotherhood and Indian caste panchayats all reinforced male dominance. As long as men are united, bound in collective loyalty, women are secondary.

How might this change?

On International Women’s Day, I’d like to highlight a hugely important (but widely overlooked) driver of gender equality. In fact, this mechanism is so powerful that it is actively suppressed by many patriarchal societies.

ROMANTIC LOVE

Curious? Well, let me share my historically comparative analysis of Pakistan, China, the Roman Empire, Early Modern Europe, Puritan settlers and present day USA.

Pakistan

Trusted networks of commerce, cooperation and mutual insurance are consolidated through cousin marriage. Land, herds and businesses are inherited by sons, who provide for their parents in old age. Female employment remains low, since men’s honour depends on female seclusion.

Sons are treasured as economic providers; his desertion spells their destitution. A son is not only valued for his earnings, but also his capacity to consolidate wider networks. Parents reaffirm kinship ties by marrying their children. Cousin marriage binds families together. Tearing away signals rejection and unreliability - as if family bonds are unimportant. Since everyone is rewarded for family loyalty, outsiders can hardly be trusted, for they have every incentive to favour their own.

Marriage is valued (for consolidating kin networks, continuing the lineage, and creating more providers), but it also poses a threat.

A son who adores his wife may neglect his parents.

Patrilineal loyalty is reinforced in several ways:

Arranged marriages;

‘Family comes first’. Socialising with family, celebrating their weddings, mourning their funerals, helping out in hard times, and discussing business ventures all reinforce family loyalty. Outsiders are eyed with suspicion. Adults may thus freely choose to marry paternal cousins.

Filial loyalty is revered. “Paradise lies at the mother’s feet” is frequently repeated. By recalling this Hadith, Pakistanis remind each other that filial loyalty was praised by the Prophet.

Romance may be repressed. Regardless of how the marriage is formed, love may still be sabotaged. Even if couples marry freely, the mother-in-law may actively prevent closeness. Tensions between wives and mothers-in-law are global, but these appear most pronounced in poor honour cultures like Pakistan, where sons are crucial for support in old age.

Repressing romance

Hussein (who grew up in a poor part of Karachi) shared that his mother (Amal) chose to marry her first cousin (Mubashir). It was a love marriage, but romance was heavily suppressed.

“My grandmother (dad’s mum) would in all these ways try to limit my mum and dad’s relationship from being deeper than it was.

She would get very annoyed if he would take her out to events.

She didn’t like it if he spent time upstairs in the flat my mum had. She wanted him downstairs in her flat, with the rest of the family.

She would keep him downstairs for as long as possible during the evening so he would not go upstairs with my mum. She once said quite bitterly, which I only understood when I was older: “Upper Kya milaga” (what will you find upstairs?). There was this implicit thing of you’ve already slept with her and had a son. What else can she give?

And she knew things like Eid shopping, intimate time in the evening, a Sunday afternoon were all possible ways they would get closer. But it was also economic. He was her main provider, so if he was swayed by his wife, then she may lose that support”.

Amal was bright, bubbly and craved independence: she wanted to play music, watch TV and go on fun trips. The standard donor intervention might be ‘income-generating activities’ or ‘female empowerment’. But that would be a gross misdiagnosis. Amal actually earned a decent salary - working as a senior administrator.

Amal’s biggest problem was in the home. Since she was barely permitted to spend any time with Mubashir, their marital bond remained weak. Tight restrictions inhibited love, empathy, consideration and understanding.

Mubashir’s prior affinity was to his mother and male peers. He valued their judgement and sought their approval. Fraternal solidarity persisted. When Amal rebelled against these strictures, he beat her to ensure submission and maintain status. Mubashir’s violence was highly strategic - designed to terrify, but not totally incapacitate. Amal’s bruises and broken bones hardly counted.

Amal wanted affection, so when Mubashir came to her room she would deny sex as a form of rebellion. But since he did not value her welfare, this just resulted in rape.

Weak conjugal attachments are an overlooked driver of patriarchy. 40% of Pakistanis think wife beating is sometimes justifiable. Even if a woman is employed, she’s just as likely to have been beaten. My point is that if men don’t love their wives, her welfare matters less.

Weak conjugal ties may also dampen female autonomy and household decision-making. Since Mubashir spent little time with his wife, why would he care for her preferences or value her counsel? Only 27% of Pakistani Muslims say that family planning is morally acceptable. 39% of married women say they do not decide about their healthcare, household purchases or social visits. I suggest that this is partly due to the suffocation of love.

Even if Pakistani women march and mobilise, all this subversion may generate backlash if powerful authorities (i.e. men) do not empathise with their struggles. Indeed, Pakistan’s Aurat march for International Women’s Day usually triggers strong hostility.

Conjugal love is highly unusual

Intensive kinship does not prohibit love, but it does make it more unusual. Hussein’s step-father’s brother (Bilal) greatly cherished his first cousin (Sumrah). Deeply devoted, Bilal wanted to please Sumrah, listen to her ideas, and make her happy.

Bilal loved Sumrah so much that her words carried weight, her wants mattered. Although they lived next door to his parents, Sumrah actually convinced Bilal to construct a physical dividing wall. By obstructing family control, they could now build a life together:

“He would take her out in the evenings with their children, just for a snack or to just have a motorbike ride. He recognised her life was just sitting at home doing childcare, making food…

Because she had no mother in law and had separated him from his family, there was no judgmental prying or social lobbying against this affection”.

The relatives were aghast! They said,

“What magic has she done to him?” (translated)

Hussein explained,

“[Pakistan] is a culture where you marry for fertility, social obligation and building kin networks. Love and the suggestion of a marriage coalition where the husband is loyal to the wife [rather than] his family and wider kin is very dangerous”.

Love is clearly possible, but it’s heavily repressed in patrilineal societies where prior loyalty is to kin and sons are paramount for support in old age. These tales from Karachi are not isolated anecdotes, I have heard precisely the same across Turkey, Morocco, and India.

Where conjugal love is suppressed, wives’ preferences matter less.

What’s the solution?

If mothers bind their sons close partly for economic support, then one option is to expand public pensions. Social protection can substitute for sons - and actually reduce male-biased sex ratios. If mothers do not fear impoverishment, they may also loosen the strings of attachment.

If that’s true, we should expect East Asia’s rapid economic development to have encouraged conjugal love.

East Asia

As East Asian women (especially educated women) moved to cities, they increasingly chose their own partners. Some also forged nuclear households. However, this appears to have been mediated by culture.

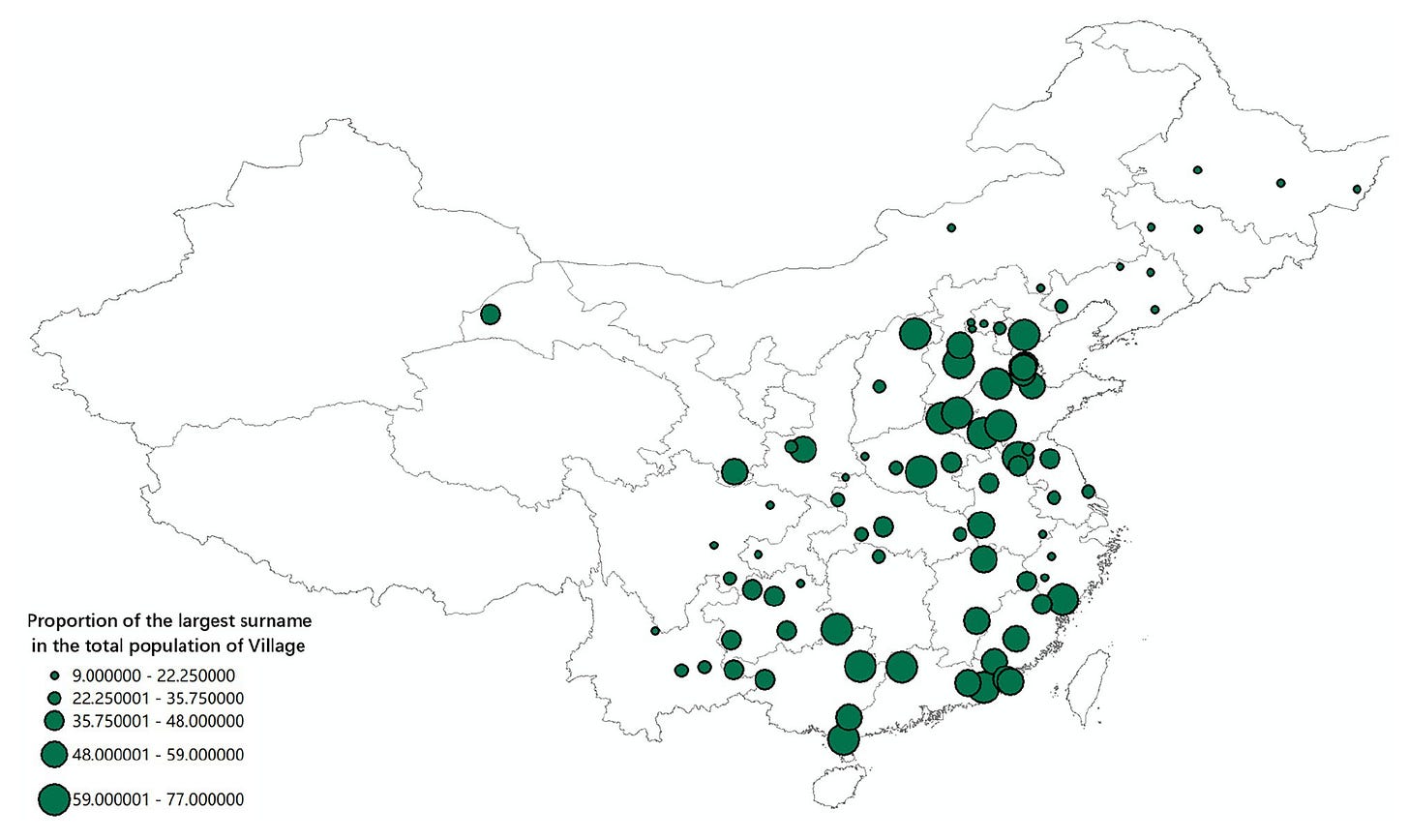

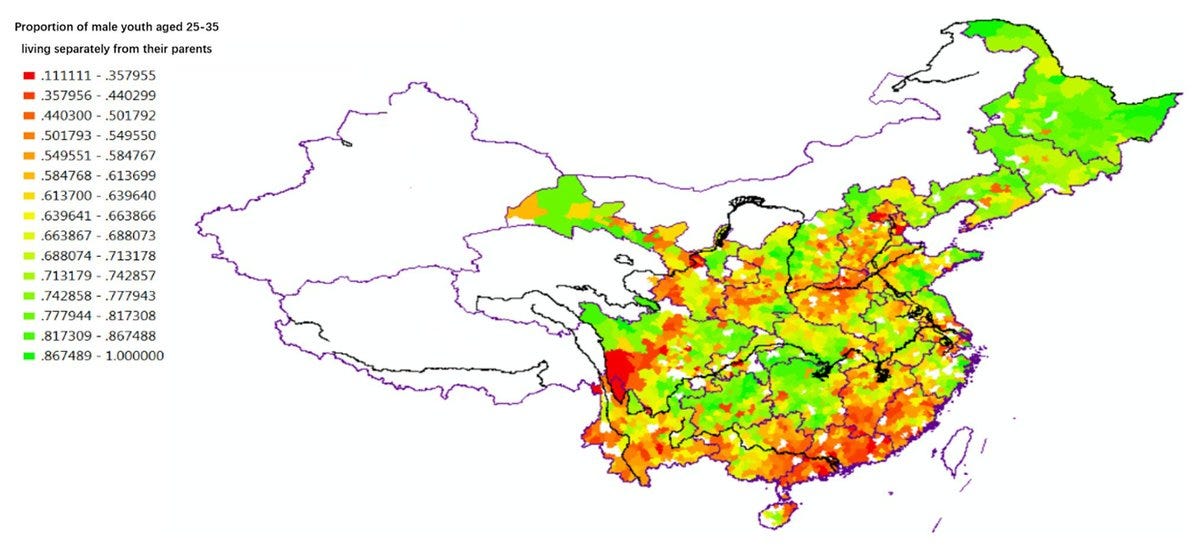

In Chinese counties where lineages were weaker and there was more surname diversity (i.e. the Yangzi River Basin and the Northeast), married men were much more likely to form their own nuclear families.

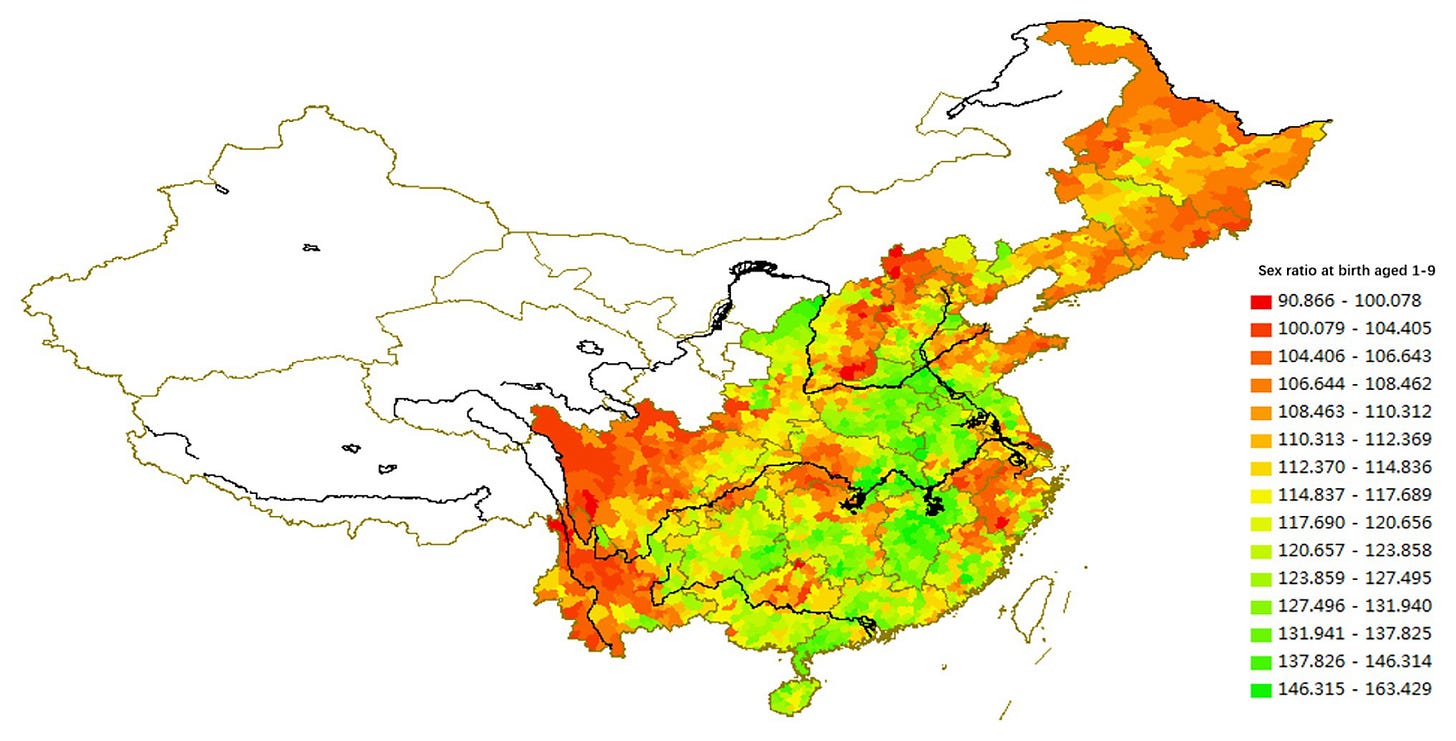

Whereas in Southern China (where clans are extremely strong), there is strong son bias, uneven sex ratios, and married men have tended to stay with their parents.

Unfortunately, I lack subnational data on ‘love’, but the available evidence suggests that where patrilineal loyalty was stronger, marital unity was less readily accepted. Economic development may encourage marital love worldwide, but it seems to be mediated by culture.

How Europeans Came to Celebrate Love

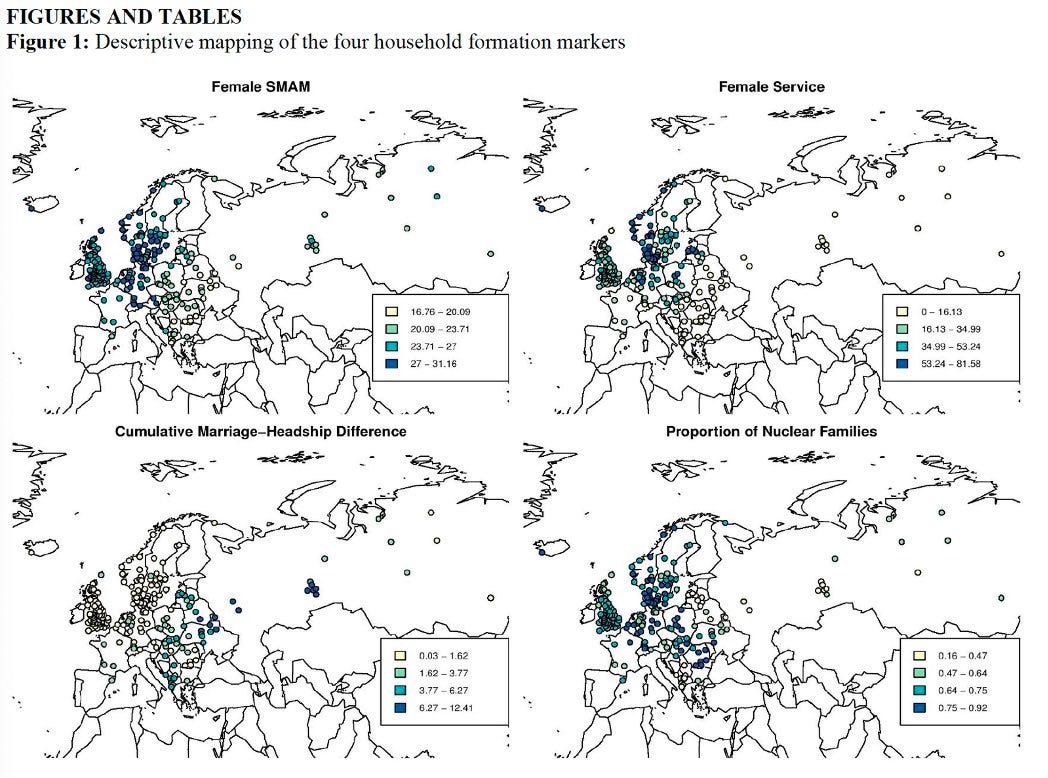

Europe used to be extremely patriarchal. Parliaments, bureaucracies, universities and religions all used to be run by fraternal networks, which reinforced male status. But there has since been rapid progress. It’s is now the world’s most gender equal region.

What’s Europe’s feminist secret? It’s not reducible to economic growth, democracy or state capacity. South Korea has all three, but recent feminist protests have triggered hostile sexism. This is “The Great Gender Divergence”. To understand it, we need to go back over two thousand years…

Ancient Rome

The Roman Republic was initially patrilineal and patriarchal. Descent was traced down the male line, solidifying fraternal loyalty. Civil and political rights were the preserve of male household heads (pater familias). He had powers (patria potestas) over his children, his wife (manus), and his slaves (dominica potestas). Manus endowed him with the authority to put her to death for adultery (or drinking alcohol). Compliant women were respected, while dissidents were shamed and sullied.

Romans and Greeks differed from other civilisations in one important respect. As Classist Walter Scheidel explains, they idealised marital monogamy*. Polygamy was seen as downright ‘barbaric’.

*Though to be clear, this was not reinforced by stipulations of male love, loyalty or sexual fidelity. A patrilineal Roman was perfectly free to rape and molest slave concubines.

Christianity and the Rise of Nuclear Families

Christianity spurred cultural and legal changes. Marriage was now supposed to be a conjugal partnership. Paul upheld a reciprocal relationship between husband and wife,

The husband must give the wife what is due to her and the wife equally has to give the husband his due. The wife cannot claim her body as her own; it is her husband’s. Equally, the husband cannot claim his body as his own; it is his wife’s

(1 Corinthians 7:3-8)”.

Marriage came to be idealised as a voluntary relationship between two people, beginning with affectio maritalis (the desire to be husband and wife). Christians were expected to be sexually faithful (“thou shalt not commit adultery”). Sexual monogamy became normative: in 5th Century CE, Augustine called it a “Roman custom”. Legally, Rome shifted from being patrilineal to bilateral: a mother’s relationship with her children was recognised by law, allowing her to inherit from them.

From 300-1300 CE, the Roman Catholic Church and Carolingian Empire stamped out cousin marriage and polygamy. Even before the Black Death, English peasants disregarded lineage and rarely exchanged work with extended kin (as revealed by Barbara Hanawalt’s fantastic analysis of coroners’ reports).

Young men and women could only marry once they had save up enough money to establish nuclear households. Nuclear household’s vulnerability necessitated married women’s continued employment. Husbands seldom objected. Trusting their wife’s competence, men bequeathed land and family affairs to her control. Couples cooperated, as a conjugal unit.

North-Western European women worked - as dairy farmers, spinners, seamstresses, hawkers, midwives and shop-keepers. In cities like London, Leiden and Paris, where economic opportunities were greater, market women were assertive, self-reliant and street-wise. Where guilds were weak, women gained professional pride in skilled crafts (like seamstresses in Old Regime France).

Wage labour was thus widespread. Precociously deep wage labour markets and urbanisation broke up kinship and accelerated exogamy.

Europe was still patriarchal

Women’s work was mostly low-skilled, unorganised and often home-based (like spinning). Before the advent of contraception, infant formula, electricity and washing machines, mothers' lives were relentlessly interrupted. 60% of their prime-age years were spent either pregnant or nursing. Screaming toddlers forestalled the pursuit of skilled trades, economic autonomy and broad social networks (beyond other similarly marginalised female kin and neighbours).

Men were far more able to seize new economic opportunities. As Europe transitioned from feudalism to commercialisation (with larger-scale more capital intensive production), men honed their crafts and travelled as merchants. German men consolidated their advantage by establishing guilds that monopolised lucrative ventures and locked women out.

Men’s dominance was entrenched by a plethora of fraternal orders - in government, the judiciary, religion, medicine and universities. Vulnerable women, with weaker social capital, struggled to protect themselves from persecution. As competing Catholic and Protestant churches sought to demonstrate their superior power to protect people from witchcraft, they burnt women in their thousands.

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation promoted a major shift in psychologies - argues Joseph Henrich. Whereas Catholics deferred to religious authorities, Protestants were supposed to read and interpret the Bible for themselves. This ideology of ‘sola scriptura’ motivated increased literacy, as well as impartial pro-sociality.

Martin Luther also glorified something else (which Henrich curiously omits), but may have also weakened fraternal loyalty. 16th century sermons increasingly emphasised marital love and intimacy - details Stephanie Coontz. Church of England wedding ceremonies began with words that you may find familiar:

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered together here in the sight of God, to joyne together this man and this woman in holy matrimony, which is an honorable state, instytuted of God in Paradise”

Weddings ended with the husband saying,

“With this ring I thee wed: with my body I thee worship; and with all my worldly goodes, I thee endow”.

By the 17th century, churches actually criticised husbands for showing insufficient love. English Puritan Robert Cleaver maintained that a husband should not treat his wife like a servant, but act in a way that would “rejoice and content her”.

This ideology is encapsulated by Frans Hals’s 17th century paintings. Like other painters in North Western Europe, his family portraits feature couples and nuclear families. In one picture, a husband holds a rose for his wife.

Life does not necessarily imitate art. Self-presentations are always carefully curated - whether it is by commissioning paintings or uploading photos to Instagram. So I do not present these paintings as evidence of marital bliss! That said, they do suggest that marital devotion was a conjugal ideal. And they sharply contrast with Korean, Rajput, and Timurid genealogies, which consistently celebrate the male lineage.

Europe and America were still extremely patriarchal

In 17th Century America, Puritan leaders were determined to suppress women and assert their mastery. Disruptive women were silenced or exiled from Massachusetts Bay. In 1672 the Massachusetts General Court passed a law that women who forgot womanly modesty were to be “gagged or set in a ducking stool and door over the head and ears three times”.

Anne Hutchinson transgressed by guiding prayer meetings, like a man. When she spoke to defend herself at her trial for ex-communication, the governor shut her up “We do not mean to discourse with those of your sex”. She miscarried and the minister declared this God’s punishment. Generations after Hutchinson’s death, churchmen said she had infected women who “crawled like vipers across the country”. Troublesome women who challenged church strictures were punished, banished, and smeared. When Mary Oliver reproached church elders she was whipped and a cleft stick was put on her tongue. State papers perpetuated rumours that disobedient women gave birth to “monsters”.

Divorce was also prohibited - by Anglican and Catholic Churches alike. The French Revolution gave couples the right to divorce in 1792, but by 1816 this was abolished. European and North American exit options remained extremely weak until the mid-1900s. Divorce prohibitions gave husbands monopsony power. Her inability to leave meant that he could be cruel, violent and horribly despotic. It’s not just that victims were forced to endure abuse, but also that he had little incentive to be kind.

But monopsonists do not necessarily exercise their monopsony power (as Suresh Naidu argues for contemporary US labour movements). If couples truly care about each other’s happiness, they may prioritise each other’s interests. If romance is mutual and egalitarian, it can actually advance gender equality. Antoine Lavoisier and Marie Anne Lavoisier’s 1788 portrait shows a man besotted. At that time, she had no right of exit, wider society was patriarchal, and female intellectuals were often denigrated. But the Lavoisiers collaborated to advance modern chemistry.

Romantic love is an under-rated driver of gender equality

In societies where sons are treasured as future providers, brides can be seen as a threat, potentially destroying family ties. Worried about losing his loyalty, mothers-in-law may try to sabotage marital romance. If a husband does not care for his wife, then her wants matter less. In Uttar Pradesh, Anukriti and colleagues have shown that women’s movements may be restricted by their mothers-in-law. My point is that sons stay silent and permit this control because of over-riding loyalty to their mothers.

Suppose an Indian woman wants to work. If her husband prioritises social approval, his answer may be “no”. This could help explain why most slum-dwelling women in Mumbai initially accepted job offers, then declined after talking to their husbands.

Culture can persist even after immigration to rich countries. In Canada, an Uzbek migrant shared that her husband would never hold hands in front of his friends. Male peers saw marital intimacy as a ‘weakness’, he had yielded too much.

After two thousand years of cultural evolution (harking back to Greco-Roman monogamy, Church bans on cousin marriage, and the Protestant Reformation), European culture tends to celebrate romantic love. While the West remained extremely patriarchal, romantic ideals were a latent asset for gender equality.

Men were encouraged to seek someone they would cherish, appreciate and adore.

Where love is mutual, and both parties deeply care about the other’s happiness, they listen and learn. When she says certain language makes her uncomfortable, he quickly takes note - rather than getting angry and lashing out. Eager for her to thrive, he shares the care-work, supports her career progression, and celebrates her wins.

Feminist activism is often celebrated by progressives, but a growing body of evidence provides reason for caution. Mobilisation can also trigger patriarchal backlash. When US states passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), men became more sexist. In Spain, feminist marches appear to have aggravated sexism and galvanised votes for the far-right. Gender sensitisation and Self-Help Groups in India led to women being publicly humiliated. In collectivist South Korea, where individual assertion is strongly disliked, the MeToo movement appears to have sparked hostile sexism.

Gender inequalities are usually explained with reference to work, wealth or social norms. My message is a little different. Let’s think about emotions: love and loyalty. I hypothesise that a man who cherishes his female partner will put her first. A potentially powerful driver of gender equality may be loving men who want women to thrive and be happy.

If I’m right, then how might love be promoted more broadly?

Public pensions, to reduce reliance on sons and discourage marital sabotage;

Television shows that normalise romantic love and loyalty?

Right now, I’m at Stanford University - hosted by Professor Alessandra Voena, who was recently awarded the De Sanctis Award for Economic Sciences and proudly cheered by her husband, Professor Neale Mahoney.

So on International Women’s Day, let’s talk about ROMANTIC LOVE!

Further Reading

“Women and Patriarchy in Roman law” by Eva Cantarella

“Monogamy and polygyny in Greece, Rome, and world history” by Walter Scheidel

“The Ties that Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England” by Barbara Hanawalt

“Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage” by Stephanie Coontz

“The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous” by Joseph Henrich

The multi-generational Oedipus Complex. Because these mothers were denied romantic relationships with their own husbands, they project their desires for affection and romance onto their sons. I'm not saying it crosses the line over into sexuality, that would be extremely rare (I hope), but the way these mothers and sons deal with each other are parallel to the way you see couples deal with each other in other cultures.

You would think an older woman would be like, "I was deprived of an affectionate marriage by my mother-in-law, but let me break this generational curse and not deprive my own dear daughter-in-law. But instead they double down and go full throtal into the weirdness. It's a mental illness and really disgusting.

So here's a question: Why isn't Amal downstairs with her husband and in-laws enjoying family bonding time with all of them? A possible answer is that in spite of living in a typical South Asian mutli-generational joint family household, Pakistanis are Muslim (the vast majority) and such a family structure runs contrary to Islamic rulings, traditions and norms because of the non-mahram rules. All of her husband's male relatives, excepting only his father, are non-mahram to her and thus she cannot be around them without being fully covered. As it is very uncomfortable for a woman to fully cover in abaya, hijab and niqab all day and night within their own homes, they often cloister in their rooms or their husbands and in-laws force them to cloister. She is not considered an intergral part of the family since upon death of her husband she is legally marriageable by any of the men in the family excepting her father-in-law. This is clearly stated in Quran. Now I doubt that most Pakistani families take it this far and many probably socialize with the wife of their brother, wife of uncle, wife of cousin, wife of nephew, etc. But for those that follow Islamic rules to the letter, they simply would not be around their brother's wife without her being fully covered in Islamic "modesty gear". And even fully covered she wouldn't be openly talking and laughing and bonding with them. This is a matter of cultural divide in the wider Islamic world. See this video where this Malaysian sheikh, stationed in Saudi Arabia, discusses how this South Asian/Desi/Sub-continental cultural custom of joint family living is not an Islamic practice at all. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HXUyMKCDBo8

Do you ever plan to do a trip to North Korea? As a gender scholar you might the place very interesting. Because the men had to work in shitty, low paid government jobs, the women became breadwinners since they were able to participate in capitalism. North Korea might become the first society to transform from a patriarchal society to a matriarchal one.