Ideals of Collective Harmony

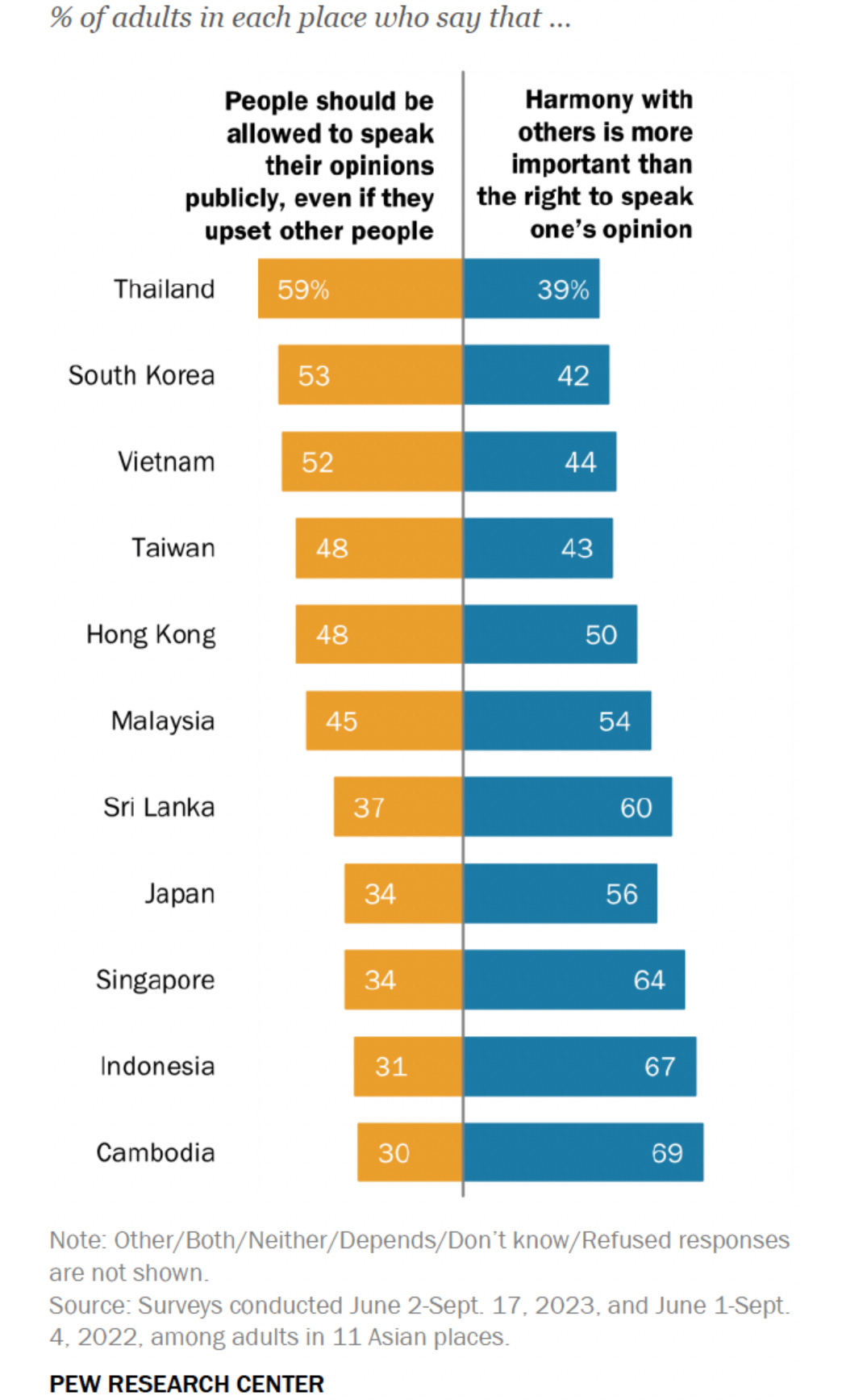

In some societies, collective harmony is more highly valued than self-expression. If people are reluctant to speak out, prior culture is more likely to persist unchallenged. Caring deeply about social approval amplifies fears of ostracism and motivates quiet conformity. Moreover, where self-assertion is strongly disliked, feminist activism is more likely to trigger patriarchal backlash. Through recent fieldwork in Mexico, Spain, Hong Kong and South Korea, I realise this is a hugely important, but widely overlooked driver of ‘the Great Gender Divergence’.

To highlight the importance of collective harmony, let me share insights from my interviews with men and women in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea. This is divided into several sections:

Ideals of Collective Harmony

Why do Ideals of Collective Harmony Persist?

Low Immigration and Cultural Homogeneity

Teacher-Centric Schooling

Support for Gender Equality, alongside Dislike of Dissent

Rebels may be Ostracised

Sexism goes Unchallenged

Victims of Sexual Abuse may remain Silent until Confident of Solidarity

Patriarchal Backlash

Ideals of Collective Harmony

East Asians tend to value collective harmony. People are more inclined to see themselves as part of a wider group and show self-restraint. Asserting one’s own wants may provoke unease and anger (especially if it challenges challenges expected hierarchies). Globally, neuroscientists find variation in the psychological anguish experienced upon social disapproval. Koreans traditionally revered ‘nunchi’: they believed one should be socially sensitive, anticipate others’ concerns, and maintain harmony. When speaking to elders, Koreans may also use more respectful language. Japanese aversion to individualism is encapsulated in the old saying:

“The nail that pops up is always hammered down”.

‘Collectivism’ is sometimes misunderstood. I must emphasise that ideals of collective harmony are perfectly compatible with economic competition: one may want to keep the peace, while simultaneously aspiring for upward social mobility.

To be clear, this distinction between collectivist and individualist does not imply an East-West binary. There is a spectrum, which seems more pronounced among certain peoples. We also see subnational heterogeneity and change over time. Culture is never set in stone. Notwithstanding these caveats, a wealth of nationally representative data clearly suggests that East and Southeast Asians are more inclined to see themselves as part of a larger group and prioritise collective harmony.

What Do Ideals of Collective Harmony Persist?

Cultures have evolved over millennia. What we observe and idealise today comes after centuries of ancestral farming, kinship organisation, brutal conquest, state development and moral evangelism.

IF YOU ARE ONLY INTERESTED IN THE EFFECTS - NOT THE CAUSES - OF CULTURAL HARMONY, SKIP THIS SECTION

In East Asia, rice-farming’s labour intensity and interdependence may have encouraged greater social awareness and concern for collective harmony. Confucianism also instilled strong hierarchies, especially after it was institutionalised by imperial dynasties. Literature also lavished praise on those who lived by cardinal virtues. Given strong returns to collectivism, parents socialised their children for conformity. (For more details, please see my previous essay: ‘Why are East Asians culturally tight collectivists?)

Through recent fieldwork, I realise two further factors that perpetuate ideals of collective harmony: low immigration and teacher-centric education.

Low immigration and cultural homogeneity

East Asians who had studied in the West or worked in internationally diverse firms always described major cultural differences and their gradual assimilation. As one professional woman from Hong Kong explained,

“In Hong Kong, I studied at a local school, you don’t raise your hand, you don’t ask stupid questions, because I felt I would get judged. Peers would judge you if you raise your hand too much, ‘are you trying to show off?’

In the US, everyone just raises their hand, and speaks what they want to speaks. I wasn’t as confident as them, but I did have a breakthrough. I felt more confident, I was in a very diverse place, I felt quite accepted. I felt confident to raise my hand, because everyone does the same.

When I came back to Hong Kong, I was more confident than before, but I was more collective, I felt I had to blend in”.

In more diverse environments, with strong norms of self-assertion, East Asian men and women said they felt more comfortable speaking out. Korean women who worked in foreign firms often told me, “it’s very international, I don’t have to do nunchi”.

However, such experiences are relatively uncommon in South Korea, where immigrants only comprise 4% of the population, and they are mostly East Asian. Homogeneity seems to encourage cultural tightness and dislike of difference - as argued by Michele Gelfand in her wonderful book “Rule Makers and Rule Breakers”. Hong Kong illustrates this perfectly: it is much more liberal and people pride themselves on enjoying the melting pot of East and West.

Teacher-Centric Schooling

East Asian students tend to top internationally comparative tests for reading and writing. Students are excellent at these exams. Nevertheless, East Asian governments and educational experts have expressed concerns that schools over-emphasise rote learning and memorisation. This is consistent with my interviews. East Asians overwhelmingly described their education as listening to the teacher, while remaining quiet and taking notes.

In Seoul, I met three Japanese women who had recently finished high school. Together, we headed to Cats’ Playground Cafe. As the cats purred, we chatted about schooling:

“It’s top-down rote learning: you listen and memorise, you don’t give your opinion.

“It’s more about being in the middle”.

“You feel self-conscious and embarrassed, one shouldn’t be a trouble maker or kick up a fuss”.

“It’s better to take the pressure than be a trouble maker. Others will urge you to be quiet, be harmonious”

“There is no culture of being adversarial”

“Men are as introverted as women”.

Senior school administrators and academics affirmed this trend of teacher-centric education:

“One-sided lessons have been going on in Korea for a long time… The culture of discussion is very weak. This is something that needs to be improved a lot and that’s why the school board is making a lot of these policies to create a culture of discussion and discussion, but the fact is it is not actively done. I tend to get a little caught up in the entrance exams called college entrance exams… Students are nervous about each other. Students care a lot about how they're seen by their peers. Nobody wants to be a minority. Some worry about being isolated. I think it's a common in every country, but in in Korea, yes, we have a little stronger” - Korean civil servant, managing three high schools.

“There is no culture of speaking out in high school. It doesn’t do you any good if you speak out, it doesn’t improve your test score, it doesn’t improve your reputation” - Korean academic.

University students also expressed reluctance to speak out. They gave a range of reasons: not being accustomed, respect for the teacher, worrying about getting something wrong, not wanting to inconvenience others, and preference for collective harmony. In seminars, Koreans told me they tend to avoid topics that are divisive or conflictual (like gender or conscription).

A male software engineer in Seoul explained,

“We rarely discussed things. .. Even in college, we rarely discuss, and we usually listen to what the professor teaches us, it’s one-sided. Because of the culture of respecting elders, you have to be very cautious about approaching teachers” (translated).

Some people feel more emotional anguish at the prospect of negative evaluation, whereas others brush it off. This may vary worldwide. In Korean language, there are at least nine different terms to describe the psychological distress of social embarrassment. A Korean student - who spent a semester abroad in China - told me that Italians sat at the front of class and asked ‘stupid questions that were on the next page’. They had ‘no shame’. In Hong Kong, a European professor expressed the polar opposite frustration. He has repeatedly tried to encourage participation and yet students remain silent. Evidently, there are cultural differences.

How do ideals of collective harmony affect gender?

In schools and workplaces that idealise collective harmony, people may not necessarily develop the habit of speaking out. They may be perfectly comfortable in with close friends and family, but otherwise self-censor.

Even if one wishes to express dissent, it can be costly. Others who idealise harmony may feel uncomfortable and distance themselves from subversives. Rebels may be ostracised, which sows wider despondency. Without a culture of feminist consciousness, sexism often goes unchallenged. Victims of sexual abuse may remain silent until they are supremely confident in wider solidarity and social support. Even if they develop the courage to organise collective, this may generate massive backlash.

This is all detailed below, drawing on my interviews.

Support for Gender Equality, alongside Dislike of Dissent

Sang-hee (30, employed at a public enterprise in Seoul)

“I don’t like these feminists protestors. It’s too adversarial, why don’t they resolve these issues calmly?” - Sang-hee.

I nodded, expressing empathy. Chatting over coffee, I realised that Sang-hee supports gender equality, but loathes confrontation. A man was recently promoted over more experienced female colleagues. Privately, they grumbled about sexist discrimination, but otherwise stayed silent. Complaining to management was pointless and risked wider ostracism by peers.

Curious to understand Sang-hee’s views, I presented a hypothetical scenario, where a woman proposes a change to corporate culture. I role played that a woman politely puts her hand up in a company meeting and says,

“I would like to propose that we end our company drinking culture. When people drink, they may make mistakes, do things inadvertently, which can make others uncomfortable”.

I spoke softly and gently; I really tried to be extremely non-conflictual. But Sang-hee’s revulsion was evident immediately. She furled her lips, recoiled and looked visibly uncomfortable. She grimmaced, “It lacks nunchi”.

Minjun (her male friend) was equally puzzled,

“I would be amazed. I mean this positively. But why is that person imposing their views on others? Why don’t they just drop out?” (translated)

To ease their discomfort, I suggested a more sympathetic story. “Let’s suppose her boss was drunk and put his hand on her thigh. She doesn’t want to confront her boss, but wants to solve it indirectly”. Sang-hee was still displeased, adding

“We care about the opinion of others”.

Ideals of collective harmony thus mean that Sang-hee dislikes feminist activism, remained silent amid discrimination, and feels uncomfortable about relatively mild attempts to make the workplace more inclusive. This holds even though she privately supports gender equality. Through more interviews, I realised this is a common trend.

Jin Ae (45, female professional)

“Are you a feminist?”, Jin Ae asked, the minute we sat down for coffee.

“No. I research gender, but only as a social scientist. I don’t have a particular ideology. I’m just looking at the data.

“I don’t like feminism, they’re too adversarial and aggressive. I feel uncomfortable. But gender discrimination is very real.

Jin Ae proceeded to divulge major grievances, which had been very upsetting. Last year, when assessing different job candidates, her boss subtly signalled his preference. Silently, he pointed one finger. Nonetheless, Jin Ae ranked another candidate more highly. When her boss discovered this, he erupted in anger, infuriated by her subversion. Afraid of getting a reputation as a trouble-maker, she stayed silent.

Another time, male colleagues went to a karaoke bar. Jin Ae arrived later, only to find that they had hired a private room and paid for a ‘helper’ (a sexy woman to serve them drinks). She was horrified.

“You shouldn’t be surprised by this, at your age” - retorted her boss, implicitly chiding her for being revulsed.

Jin Ae was clearly upset. Over several hours, she bemoaned unfairness. And yet, the very first thing she said to me was that feminists are too adversarial. She appeared to have internalised a preference for harmony, alongside a commitment to equality.

Rebels may be Ostracised

Korean, Hong Kong, Chinese and Japanese interviewees often described their workplaces (especially large firms) as hierarchical. If superiors are accustomed to deference, they may react angrily to insubordination (especially from juniors/ women).

Backlash does not just come from bosses. Rebels may also discover that they have lost friends and been alienated. This clearly prevents cultural change. Fearing ostracism, others conform, but this only perpetuates pluralistic ignorance and despondency. Colleagues may interpret silence as implicit support for the status quo.

Sexism goes Unchallenged

Office politics is a dangerous game. No one wants to get on the wrong side of management and lose their job. Economists with no appetite for cultural explanations could say that silence in the face of workplace discrimination is entirely due to material self-interest. But in South Korea, I saw many non-economic instances where sexism goes unchallenged.

The National Museum of Korea is vast, expansive, and truly excellent. The collection is also extremely patriarchal. There are many paintings, artefacts, genealogies, stories, and depictions of men’s historical roles, but absolutely no mention of women. It’s almost as if there were no women in Korean history. Now, in part this reflects the reality of patriarchy. But the Silla dynasty (57 BCE – 935 CE) had three queens, and yet they are absent.

Afterwards, I chatted to two sales assistants at a jewellery shop. I described my observations and asked what they thought of it. For them, it wasn’t a problem. They knew there was one Silla Queen. But they were not remotely concerned.

From the 1970s, Western feminist anthropologists, archaeologists and historians have lambasted male-centric narratives, for ignoring women’s agency, power, and contributions. Under sustained feminist pressure, Western museums have become much more ‘woke’. They try to show more diversity. Without that same culture of self-assertion, this does not appear to have occurred yet in South Korea.

Victims of Sexual Abuse may remain Silent until Confident in Solidarity

Ideals of collective harmony are clearly no barrier to contentious politics. Taiwan and South Korea are both thriving democracies. Hong Kong was too, before 2019.

But in cultures where people fear ostracism, they may remain silent on certain issues until they anticipate strong solidarity and strength in numbers. Japan had no movement for MeToo. It didn’t reach the necessary critical mass to overcome individual fears of disapproval. Women remained silent.

Taiwan did not see massive mobilisation in 2016. It was only in 2023 - after a Netflix show “Wave Makers” depicted sexual harassment by Taiwanese politicians - that a wave of survivors came forward. Sympathetic media and ensuing public conversations may have raised their confidence in public support.

Many victims still remain silent. In our conversations, some emphasised concerns for the wider group. In Hong Kong, a female professional told me she was molested on a bus, but remained silent. Society wouldn’t like her inconveniencing them all by screaming and stopping the bus - she explained. She explicitly prioritised the wider collective.

Patriarchal Backlash

Feminist activism and advances can trigger patriarchal backlash.

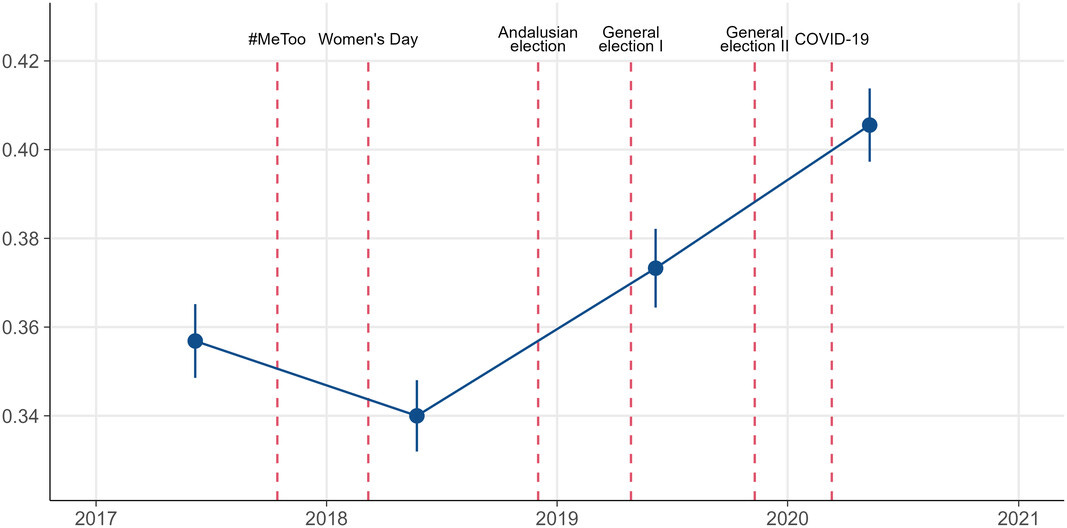

When US states passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) - guaranteeing equal rights - men became more sexist. Likewise in Spain, feminist marches appear to have aggravated sexism and galvanised votes for the far-right.

If one group feels entitled to deference and high status, they may feel personally attacked when low status group demand greater rights and protections. Cultural entrepreneurs can capitalise on patriarchal anxieties by mobilising their media networks and highlighting statistically rare occasions of false accusations.

Feminist activism is not just a battle over status, it can also be aggressive and divisive. Clearly, this clashes with ideals of collective harmony.

From 2016 to 2019, South Koreans saw an eruption of feminist activism. Thousands of women marched against spycams and impunity for sexual abuse. Resolute in solidarity, they shouted back, “My life is not your porn”

As with any political movement, there was a wide spectrum of voices. Some were more radical. ‘Megalians’ mirrored aggressively misogynist language, by mocking men’s little penises.

Feminist activism then triggered a massive counter-reaction, especially among young men. Political and cultural entrepreneurs mobilised the masses.

“We don’t hate women, and we don’t oppose elevating their rights,” said Bae In-kyu, 31, the head of Man on Solidarity, one of the country’s most active anti-feminist groups. “But feminists are a social evil” (quoted in the NYT).

Yoon Suk Yeol launched a successful campaign for president, by politicising mandatory conscription and defining himself as an anti-feminist.

If you look at the timings, it is precisely after 2016 feminist activism when young Korean men lurched to the right. This extreme hostility must be contextualised as coming from a society with strong ideals of both patriarchy and collective harmony.

TLDR

In brief, I suggest that ideals of collective harmony discourage self-assertion. Concerned to fit in, people may choose monochrome cars, keep quiet in class, refrain from speaking out and ostracise rebels. Even if people are privately supportive of gender equality, they may still feel serious discomfort when others rock the boat.

Threshold effects also come into play. If people are concerned for social approval, they may stay quiet until they are extremely confident of wider support.

Feminist activism also appears to provoke psychological discomfort (even among those who support gender equality). The timings provide strong evidence of backlash. It was exactly after the 2016 marches when Korean politicians successfully marshalled anti-feminist resistance. To put it crudely,

Patriarchy + ideals of collective harmony + feminist activism → massive backlash.

As far as I am aware, this is an original theory of how ideals of collective harmony may shape cultural contestation. I would love to see it tested and explored more widely. I look forward to presenting this theory next week at Barnard College.

As someone who's spent considerable time with adults and young, both, in their childhood - I see myself tussling between conforming and not conforming, between nunchi and nunchi. Spending time with adults of the family made me welcome the adjustment for the larger good while spending time with the young (most of them younger than me) made me feel individualistic. I am from India by the way.

I liked this article quite a bit. Regarding education, I am interested in whether you have read the research into what happens in Japanese vs American middle school math classes that showed the Japanese classes to use far *less* rote learning than the American ones.