Why are East Asians culturally tight collectivists?

East Asians typically prefer social cohesion and harmony, rather than self-expression and individualism. They are ‘culturally tight’. While Latin Americans believe it’s fine to pick and choose your friends, East Asians tend to expect group loyalty.

Why might this be? Let’s explore 4 hypotheses:

Rice

Socio-economic threats

Confucianism

Authoritarianism

These could be mutually reinforcing. In environments that reward coordination, people may teach their children to conform. Confucian ideologies may then seem more appealing, and once institutionalised favour people with certain psychologies.

And even after millennia of cultural evolution, nothing is set is stone. It is continually contested - as I will demonstrate in the case of South Korea.

My goal (and perhaps yours too) is to understand this historical process.

First, check out the descriptive data 👇

Rice

Paddy rice farming was very different from wheat, corn and potatoes. It required double the labour per hectare as wheat farming. Sharing labour became essential. Keeping paddy rice permanently flooded also required cooperation. Farmers coordinated to regulate water levels, the distribution of water between fields, and canal repair.

Has this ancestral technology shaped culture?

Thomas Talhelm and colleagues find that rice-farming is associated with cultural tightness. This holds worldwide and within China. Wheat is grown in China’s arid north; rice is grown the wetter south. High school students from rice-growing counties tend to think more holistically.

Thanks to the Yellow River, rice can also be grown on a few isolated counties in north China. Students from these rice-growing communities also think more holistically, favour their in-group, and show less individualism.

This theory also holds up for 1900 USA. People from counties where crops required more labour were less individualistic. This paper by Martin Fiszbein and colleagues is useful, as it tests the effects of agrarian interdependence in the absence of Confucian culture and institutions.

Socio-economic threats

Cultural tightness is high amongst communities that have experienced socio-ecological threats (like pathogens, disasters, harsh climates, population density, resource scarcity and conflict).

This holds both internationally and within the US - as demonstrated by Michele Gelfand and co-authors. Earthquakes and droughts likewise increase religosity. Terrorism similarly increases votes for the far-right.

Existential threats may trigger anxiety, motivating group conformity and normative policing. Fearful people want their group to be strong and united in solidarity. They rally in support of authoritarian leaders and strictly punish norm violators.

But what about Latin America? Violence is surely a terrifying existential threat, yet crime persists alongside cultural looseness.

Confucianism

Confucianism emphasises subordination to one’s parents, one’s husband and ultimately the emperor. For over two thousand years, China’s rulers instilled these norms.

Guess what?

Crop failures triggered fewer peasant rebellions in counties with more Confucian temples and widow chastity. Even if people were starving, culture appears to have suppressed dissent.

Culture matters - even controlling for state capacity (as proxied by imperial soldiers, granaries, land taxes and a county’s political status).

Authoritarianism

Confucianism became hegemonic under authoritarianism, so we ought to disentangle the two.

Since the 6th century, China’s bureaucrats have been selected through the keju civil service exams. This meritocratic institution has been enormously important - argues Yasheng Huang in “The Rise and Fall of the East”. To overcome resistance from aristocratic families, Empress Wu Zetian opened up the bureaucracy. Tens of thousands came.

The keju provided a meritocratic pathway to respectability. Candidates wrote their answers in a private booth, their answers then were transcribed. Double-blind exams. It was the premium channel to upwards mobility - far more efficient than commerce, religion, intelligentsia and political opposition. This was common knowledge - suggests Yasheng Huang. Stories about commoners being propelled to the elite functioned as an ‘opium of the masses’. The Chinese dream, so to speak.

If you memorised Confucianism, you could achieve great riches.

So that’s a pretty good incentive for Confucianism. During the Ming, two to three million men regularly took the qualifying tests. The most intelligent and ambitious men spend years (if not decades) memorising ancient texts. Answers were already established; there was no room for questioning or creativity. The keju system was also adopted in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.

Confucianism may have also spread via prestige bias. Literature lavished praise on women who sacrificed for their families. Foot-binding coincided with bureaucratic expansion under the Song. Girls’ feet were broken and bound, in the hope of attracting an upstart Confucian.

But maybe China was already culturally tight - due to threats or paddy rice?

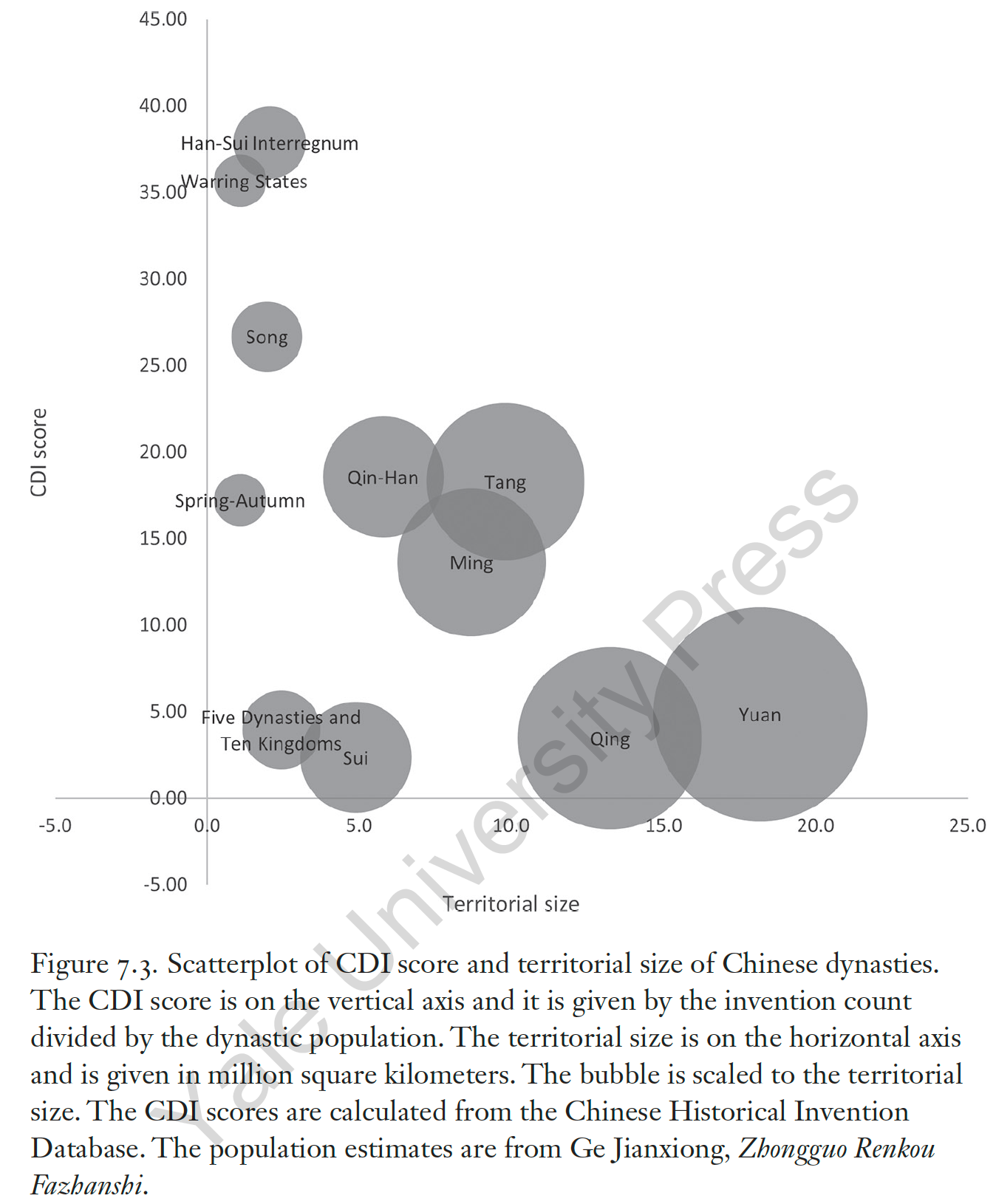

Well, there’s some evidence of change over time. During the Han-Sui Interregnum and Warring-States period, China produced a plethora of inventions. Creativity peaked when China was politically fragmented and ideologically diverse.

Absent centralised authority, China had a Golden Age of Philosophy, “The Hundred Schools of Thought”. This included the more female-friendly Daoism.

Perhaps cultural tightness stems not from agrarian interdependence, but authoritarian institutions, which then spread across East Asia?

What about South Korea?

Korea was historically rice-based. But this did not preclude ideological diversity. Totemism, Shamanism, Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism all competed. Patriarchal strictures were far weaker. Shamans were usually women. Three empresses led the Silla Kingdom. When Chinese scholars travelled to Korea, they were horrified to discover that men and women mixed at night-time musical performances. Korean daughters also inherited land and could perform ancestral rituals.

Cultural homogenisation may have been institionalised by the gwageo imperial examinations (958 to 1894). During the Joseon Dynasty, the exams were glorified. A family could only be considered noble if one member (from the last four generations) had passed the gwageo and served in government. The crimson certificate was treasured and handed down from generations. Aristocratic status depended on Confucian memorisation.

Centuries of Confucian authoritarianism did not prohibit rapid economic growth, however. South Korea has since developed a wealthy economy, a militant labour movement, a strong democracy, and massive rallies for #MeToo. V-dem ranks it as one of the world’s most democratic countries.

Despite all this disruption, South Korea still scores as culturally tight. In fact, it is one of the tightest societies in Gelfand et al’s international sample. How then can we explain mass resistance?

Look at these Korean marches for #MeToo. What do you notice?

Each rally is choreographed and colour coordinated.

By contrast, London’s 2018 Times Up rally looks veritably messy. Individuals came with their own signs, slogans, and outfits.

Cultural tightness is clearly no barrier to contentious politics, as shown by South Korea’s democratisation.

But it may create a threshold effect. If everyone else is silent, individuals who fear social disapproval may be extremely reluctant to speak out. Sympathisers may only grow bolder when confident of wider solidarity and strength in numbers.

This may help explain why Japan had no MeToo. It didn’t reach the necessary critical mass to overcome individual fears of disapproval. Women remained silent.

TLDR

East Asians score highly for cultural tightness. The available evidence points to ancestral rice farming, socio-economic threats, Confucianism and institutions. It’s difficult to disentangle their relative importance. Sorry if you think it’s a cop-out, but I’m tempted to believe in a story of mutually reinforcing co-evolution.

I always found the idea that rice farming societies are more conformist very strange. Bengal was also a majority rice farming society but we have the stereotype of a Bengali being very prone to political violence. Perhaps that's specific to the urban culture of Dhaka and Kolkata.

As an East Asian, I've thought a lot about this in general. There are some problems I have with the hypotheses. I know people love the Talhelm story because it feeds that puzzle brain, simple, mechanistic story... part of our economics/stat brain dominance.

There are massive public works projects of a sort you don't see in the West, especially related to water: Grand Canal and Angkor Wat. But, I forget when it was but the proliferation of modern rice variants that need to be flooded or in standing water are a newer phenomenon. I don't have the dating offhand, but I would guess 800-1000 CE. Prior to that, the rice variants needed less coordination for water.

But, if you use say Nisbett's historical narrative of 200 BCE China/Greece from Geography of Thought... much of the precursors of collectivism/individualism are already in place. The debate bro culture of Greece vs. the pragmatism of Confucius. A culture rooted in individuality, logic, and deduction v. ying/yang- two things true at once. Good empirical example of this is the per capita lawyers in the west v. east. Many Chinese like to mention that there is not a word/idiom in Chinese for philosophy.

Here's something of interest and I don't know how it would fit. I am not a person heavily invested in the genetics/hbd debate, but Razib Khan has written a couple of Ancient DNA substacks/podcasts and I'm going to paraphrase. There is no genetic continuity between most modern Europeans, say Germans with the peoples' of those same geographic areas 4000+ years ago. I think he portrays the Yamnaya culture (steppe nomads) as wiping out all the former farmers in Europe. East Asians were semi genetically isolated due to geographical constraints and climatic events and are still directly descended from people in those geographic areas 35k - 45k+ years ago. It's been more of a continuous society/culture for a longer time period.