Rose-Tinted Patriarchy

Since the 1970s, many feminist anthropologists, archaeologists and economists have sought to highlight women’s agency, ‘hidden power’, and unrecognised labour force participation.

This was well-intentioned. They sought to correct colonisers’ bias, male-centric histories, and statisticians who ignore women’s contributions. But rose-tinted analyses do not advance our understanding of actually existing patriarchy.

Agency

Racist colonisers portrayed Ottoman women as passive victims of oppression. Lord Cromer (Governor of Egypt) thus justified imperialism as a ’civilising mission'.

Reacting to these racist and ignorant tropes, postcolonial gender scholars have tended to emphasise women’s agency and resistance, within structural constraints. Persian concubines were cunning: they covertly orchestrated senior positions for their sons. ‘Weapons of the weak’ also include the withdrawal of domestic and agricultural labour, resisting husbands’ appropriation of their labour, refusing intercourse, spirit possession, and silence.

This is all true.

Colonisers were wrong. Women had agency. But so does everyone! We all consciously reflect - considering trade-offs and potential penalties. These choices are a product of our socialised desires and concerns for social approval. In Rajasthan, sati was so glorified that elite widows threw themselves onto the funeral pyre.

In Malaysia, women’s autonomy was so restricted that a 14 year old only escaped an arranged marriage by feigning madness.

Yes, myriad women have agency and seek to advance their secure goals.

The important question for me is not how women tried to resist, but why they were subjugated.

Labour force participation

Feminist economists have taken a parallel approach to labour economics: highlighting women’s hidden contributions.

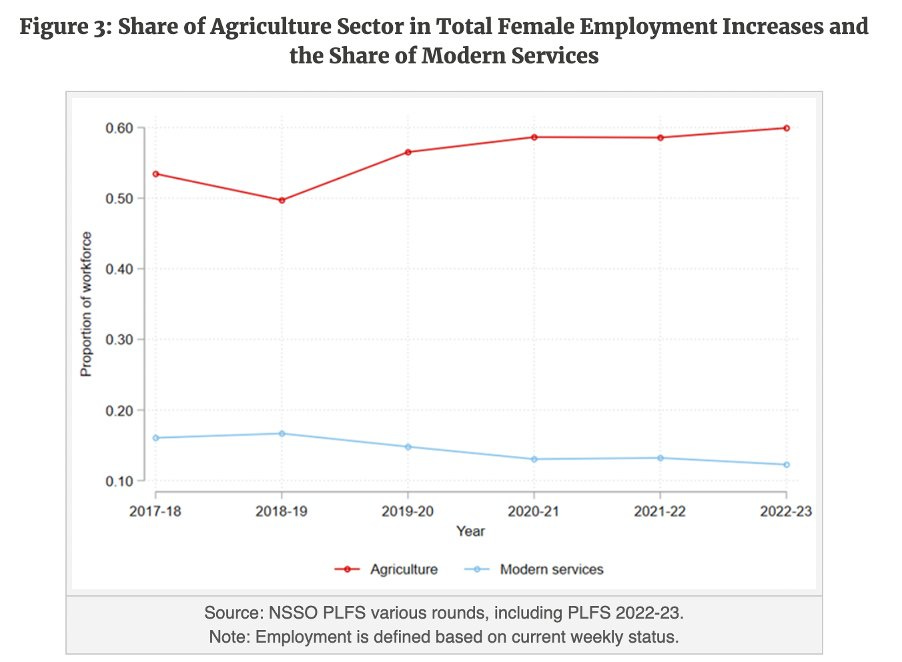

Some argue that home production is undercounted in statistics of female labour force participation. When West Bengal’s rate of female labour force participation is expanded to include all economic activities that enable households to save expenditure, it rises from 28% to 52%.

But not every kind of work is emancipatory. Farm-work does not raise women's esteem, autonomy or protection from violence.

Under Communism, female labour force participation was high. But Central Asian women largely remained in traditional villages and worked on collective farms. Such drudgery did not enhance status.

Rural women's contributions are scarcely considered 'work' by men, and sometimes, even by women themselves. Even if northern Indian women work long days harvesting crops, pounding grain and fetching firewood, they still eat last. As a 19th century Haryana saying goes, "jeore se nara ghisna hai": women as cattle bound, working and enduring all.

When women work for family-owned enterprises, they remain under the control of kin. Market, factory and office employment offer far greater possibilities for female solidarity. Through paid work in the public sphere, women gain esteem, build diverse friendships, discover more egalitarian alternatives, collectively criticise patriarchal privileges, and become emboldened to resist unfairness.

Of all women workers in India, only 15% are in services. Only a tiny tiny minority have the opportunity to mix and mingle, build friendships and expand their horizons.

So whilst the mismeasurement of female labour force participation does erase women’s valuable contributions to their households, it correctly tracks the kinds of work which provide pathways towards female emancipation and solidarity.

Attempts to correctly enumerate women’s home-based work may please statisticians, but tell us little about patriarchy.

Women’s share of paid work in the public sphere varies significantly across the world. This is both a cause and consequence of the global heterogeneity in gender relations.

Paid work in the public sphere is always counted and heterogeneity in this regard reflects substantive differences in gender relations around the world.

Celebrating female agency, resistance and labour force contributions creates a ‘rose-tinted patriarchy’. Perfectly true, but if we’re interested in why some societies are so patriarchal, we need to shift tack and ask different questions.

So a patriarchal capitalist system gives women Solidarity only outside the home?

Hi Alice, thanks for another wonderful post. The first part on agency reminded me of the film Eyes of Stone:

http://www.nilitavachani.com/eyes-of-stone-synopsis.html

I attended a screening for this at NYU a few years ago and still remember many details. In particular, it's never clear whether the possession is real or feigned, but it serves a purpose.