How do Men come to Value Female Talent?

The BEST Economics paper of 2024?

Peggy Olson’s ingenious pitches were often met with blank stares and patronising smirks. In the 1960s world of ‘Mad Men’, women were supposed to look pretty and fetch the coffee.

When men comprised the lion’s share of creative designers and politicians, they were naturally presumed more competent. Confirmation bias means that we tend to pay more attention to information that fits with our priors and ignore disconfirming evidence. Even if ambitious women like Peggy share brilliant ideas, no one is listening.

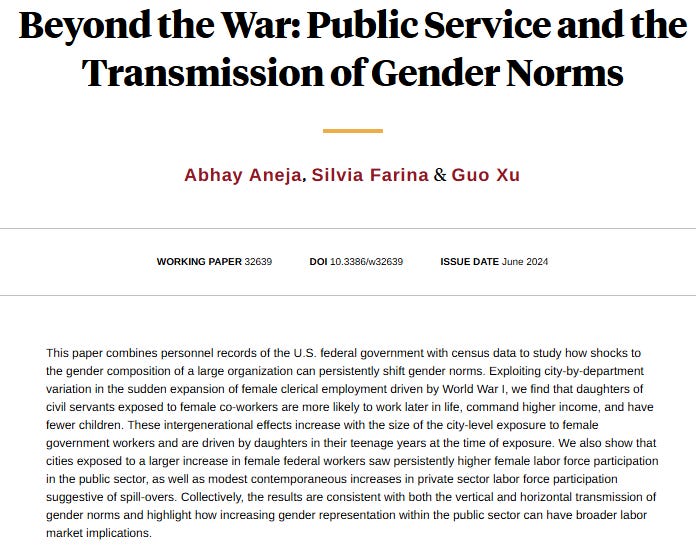

Too often, it’s presumed that to advance equality we must empower women. In truth, we need to understand how men, like Don Draper, come to value women’s contributions and become their champions. Abhay Aneja, Silvia Farina, and Guo Xu have a new Economics paper which does precisely this, and will blow your mind with its earth-shattering brilliance. Buckle up, let’s unpack this fabulous paper, explore its empirical strategy, and consider global parallels.

A Wartime Exogenous Shock!

During the World War I, the US federal government was short on civil servants and actively recruited women. Abhay Aneja, Silvia Farina, and Guo Xu examine how this increase in female co-workers affected men’s marriage choices and their daughters’ labour force participation. They find that men with multiple female colleagues were subsequently more likely to marry working women and father careerist daughters! Crucially, the effect is larger when men have many female colleagues and it becomes perfectly conventional.

First up, here is the initial shift:

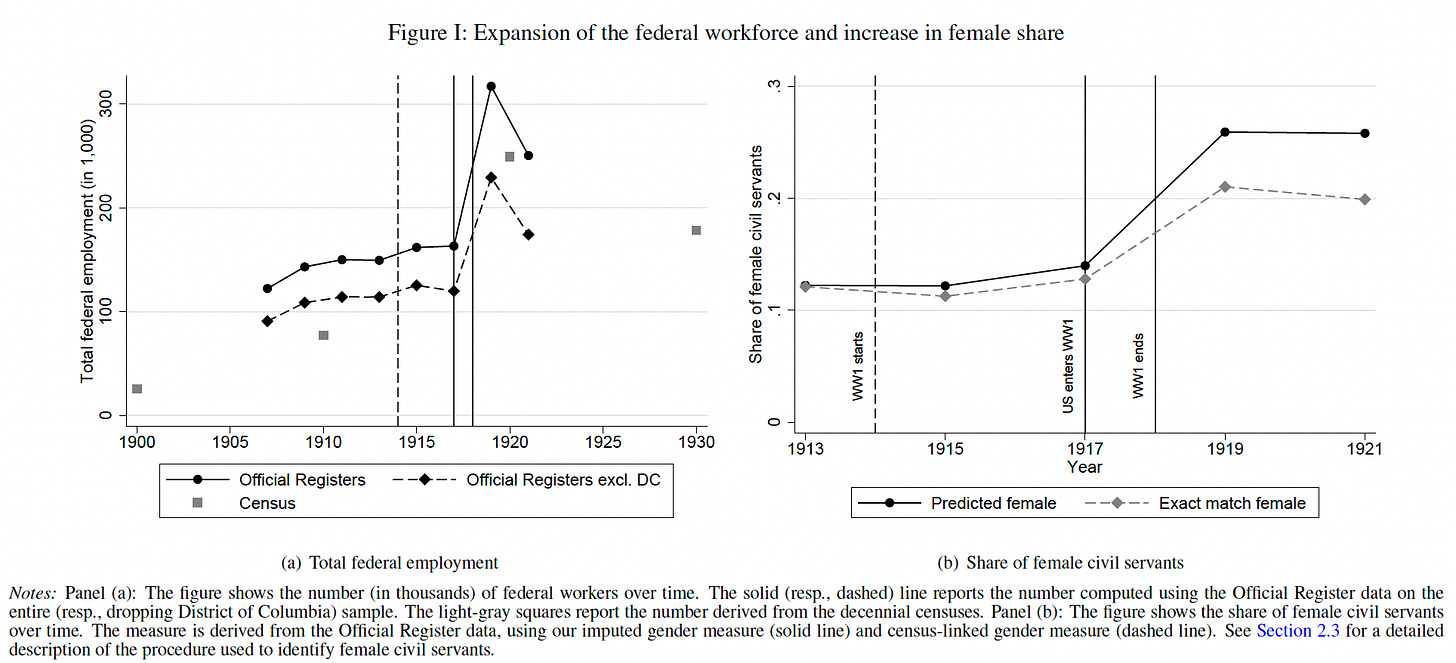

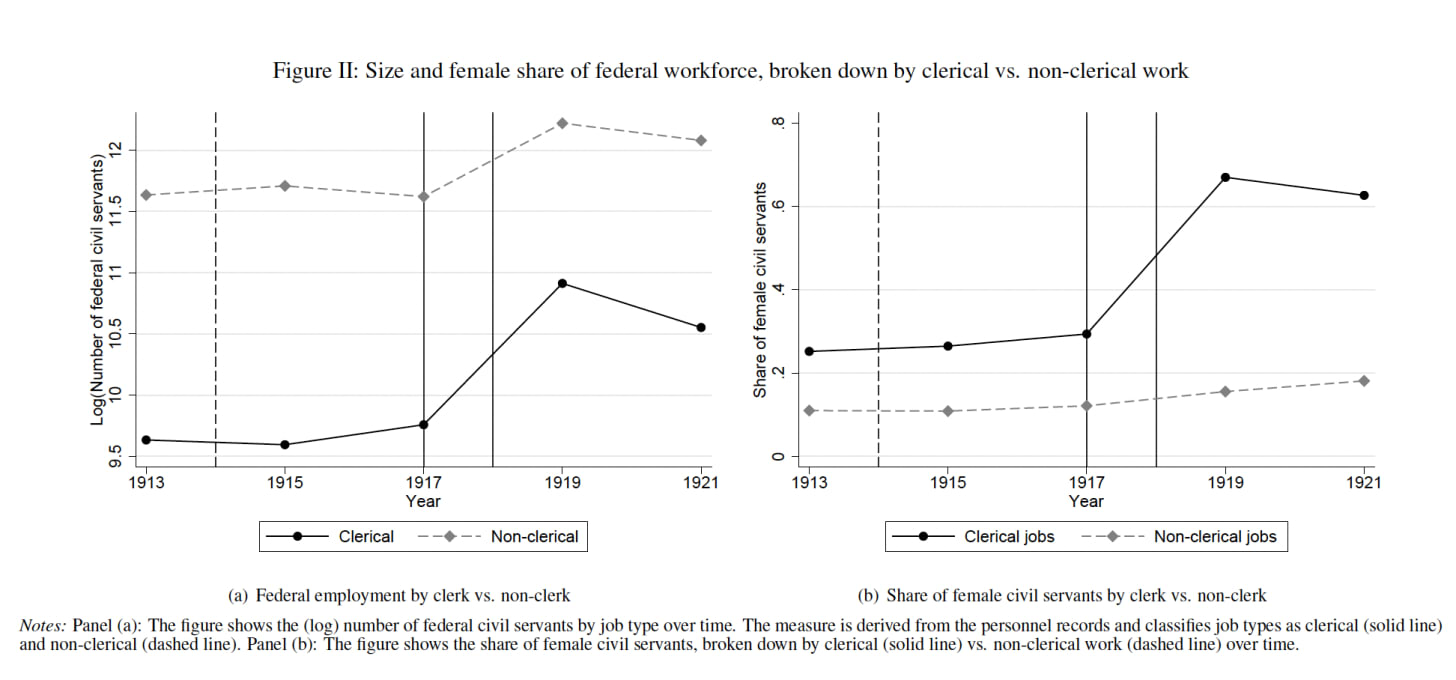

Wartime administrative demands drove an expansion of clerical jobs.

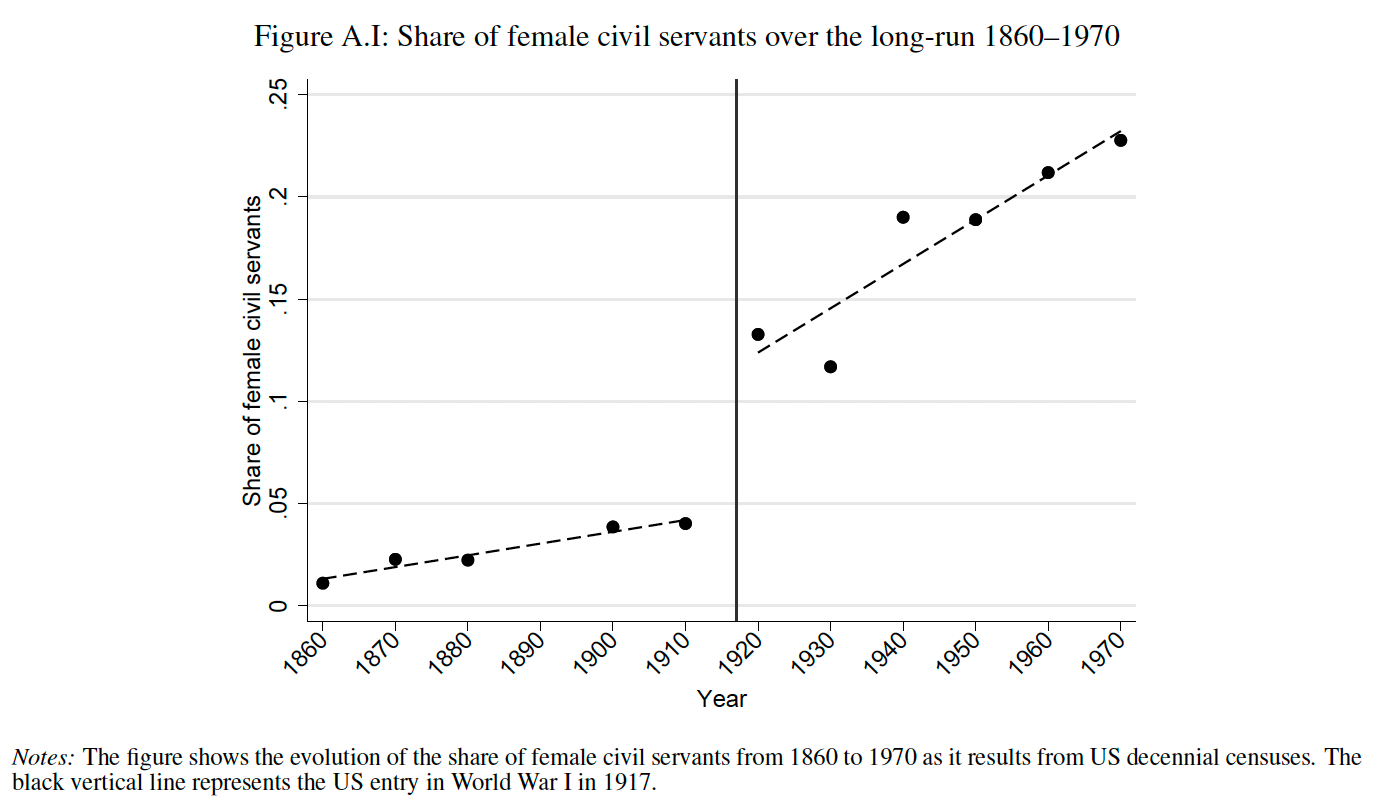

Within 2 years of entering WWI, the share of female civil servants had more than doubled.

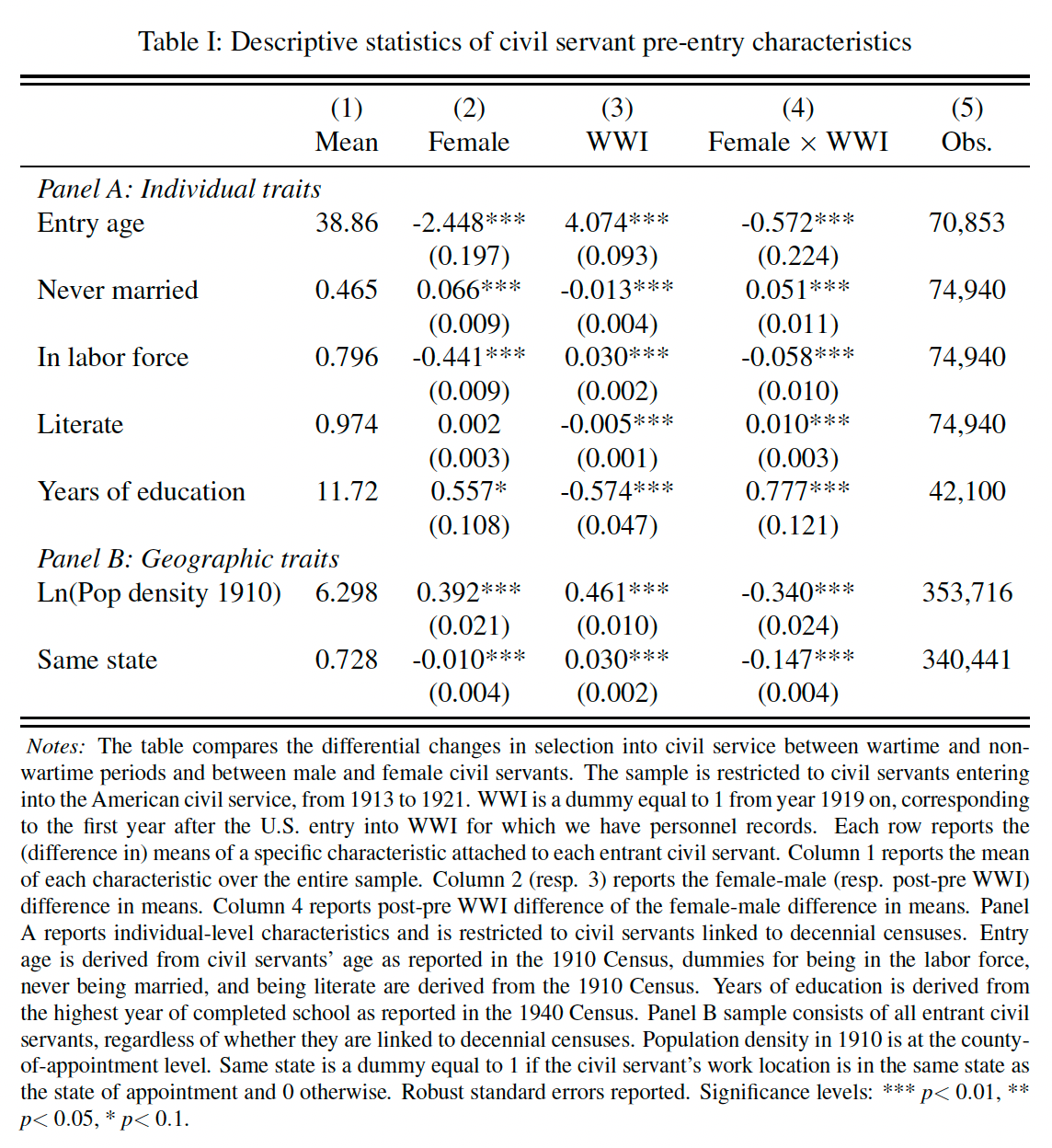

Before WWI, male and female civil servants were similarly educated.

Wartime female civil servants had significantly higher education than their male counterparts. WWI thus appears to have mobilised untapped talent.

Empirical strategy

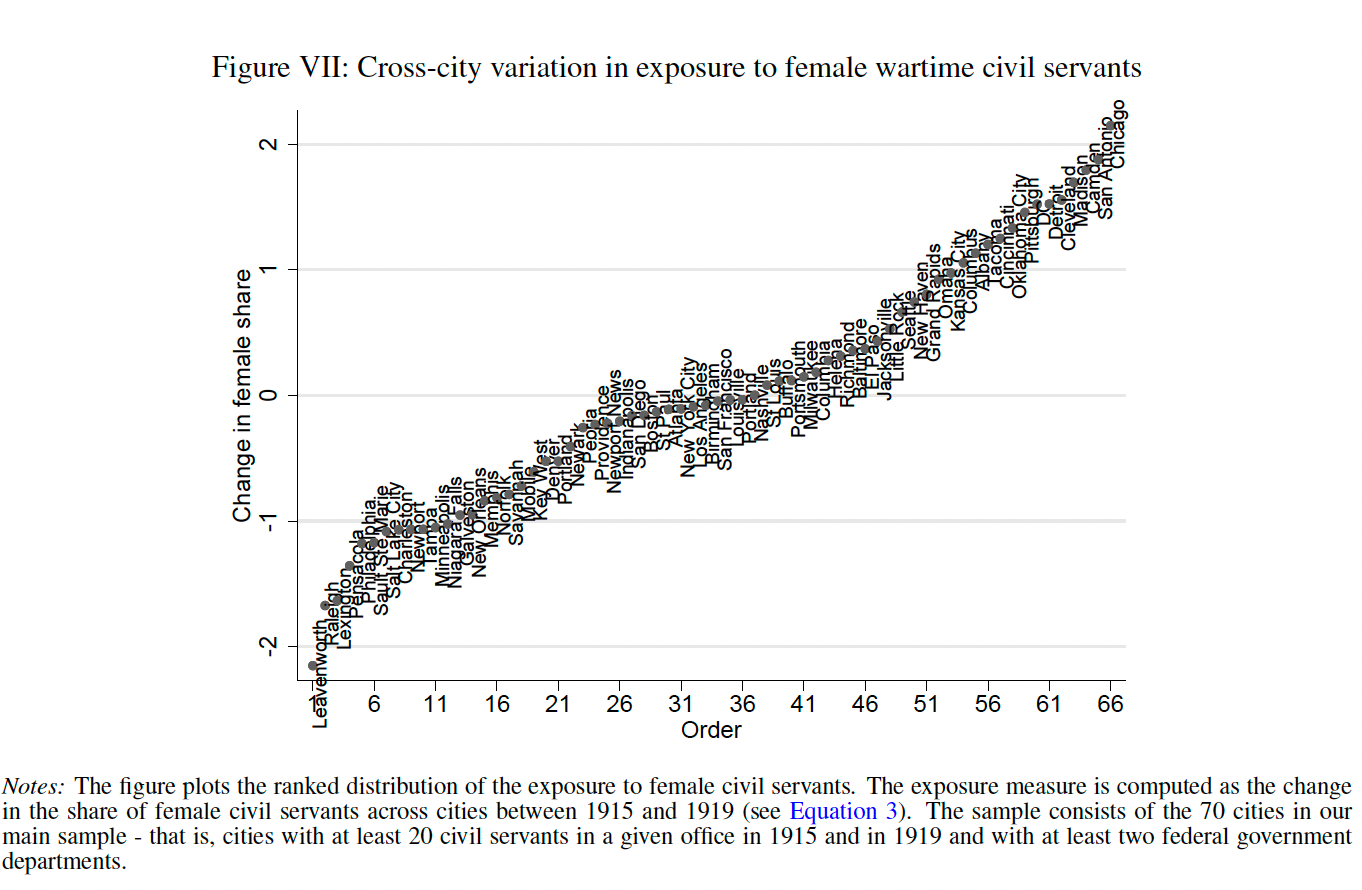

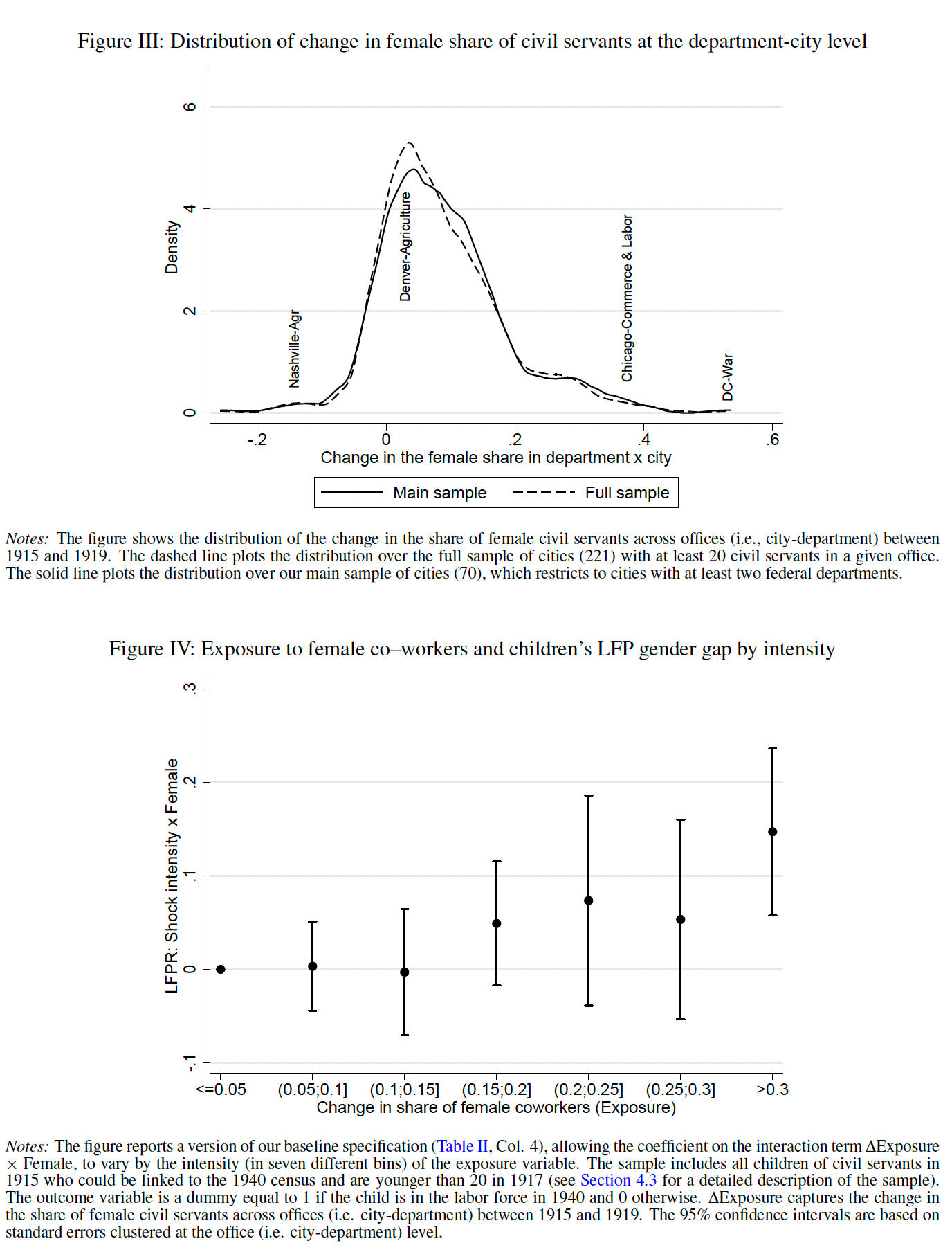

Aneja, Farina, and Xu combine newly digitised U.S. federal government personnel records (1913-1921) with full-count decennial Census data (1900-1940). At the heart of their strategy is a granular measure of exposure to female co-workers, constructed at the city-by-department level, which captures the change in the share of female civil servants between 1915 and 1919.

This measure exploits the sudden expansion of female clerical employment driven by World War I, providing a quasi-experimental setting to study the impact of exposure to female co-workers across different government offices.

But wait a minute, is this reaaally exogenous?

Maybe progressive departments were more likely to hire women? Aneja and colleagues eliminate this risk by exploiting variation in exposure within the same city (across departments) and variation across departments (in the same city). They then link civil servants to their children in the census data, tracing these children's outcomes into adulthood as observed in the 1940 census.

This intergenerational analysis is complemented by a neat ‘movers’ design, examining outcomes for children who relocated from their parents’ original city, thus disentangling the effects of changing norms from local labor market conditions.

The authors broaden their analysis with a city-level difference-in-differences approach, to calculate wider impacts on the labor market.

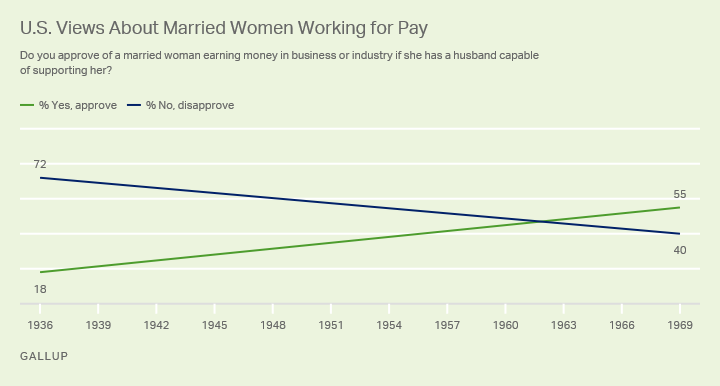

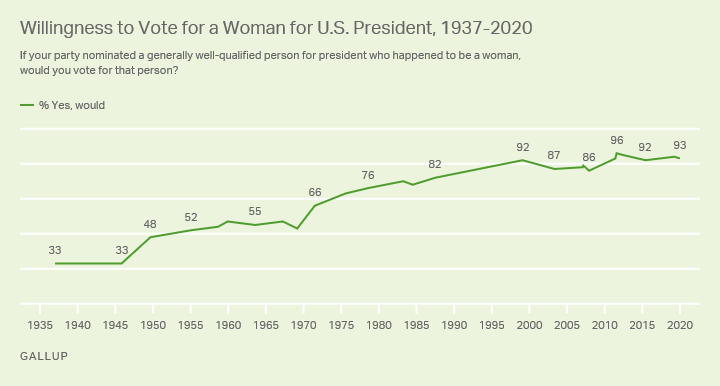

In the 1940s, female talent was widely devalued

Only 18% of Americans approved of married women working. Only a third said they’d support a female President. Employment was similarly skewed. On average, daughters of civil servants were 48 percentage points less likely than sons to be in the labour force.

Now, how did it differ for daughters of men who had worked alongside women?

More Women Co-Workers, More Employed Daughters!

Abhay Aneja and colleagues reveal that daughters of civil servants who were more exposed to female co-workers during WWI were significantly more likely to work. For each standard deviation increase in exposure to female co-workers, the gender gap in labor force participation for children narrowed by over 4 percentage points. This represents a 9% decline in the average labor force participation gap. Importantly, these effects were

Driven by increased labor force participation of daughters (sons are unaffected)

Strongest for children who, at the time of exposure, were teenagers

Present even for children who moved away from their parents’ original city

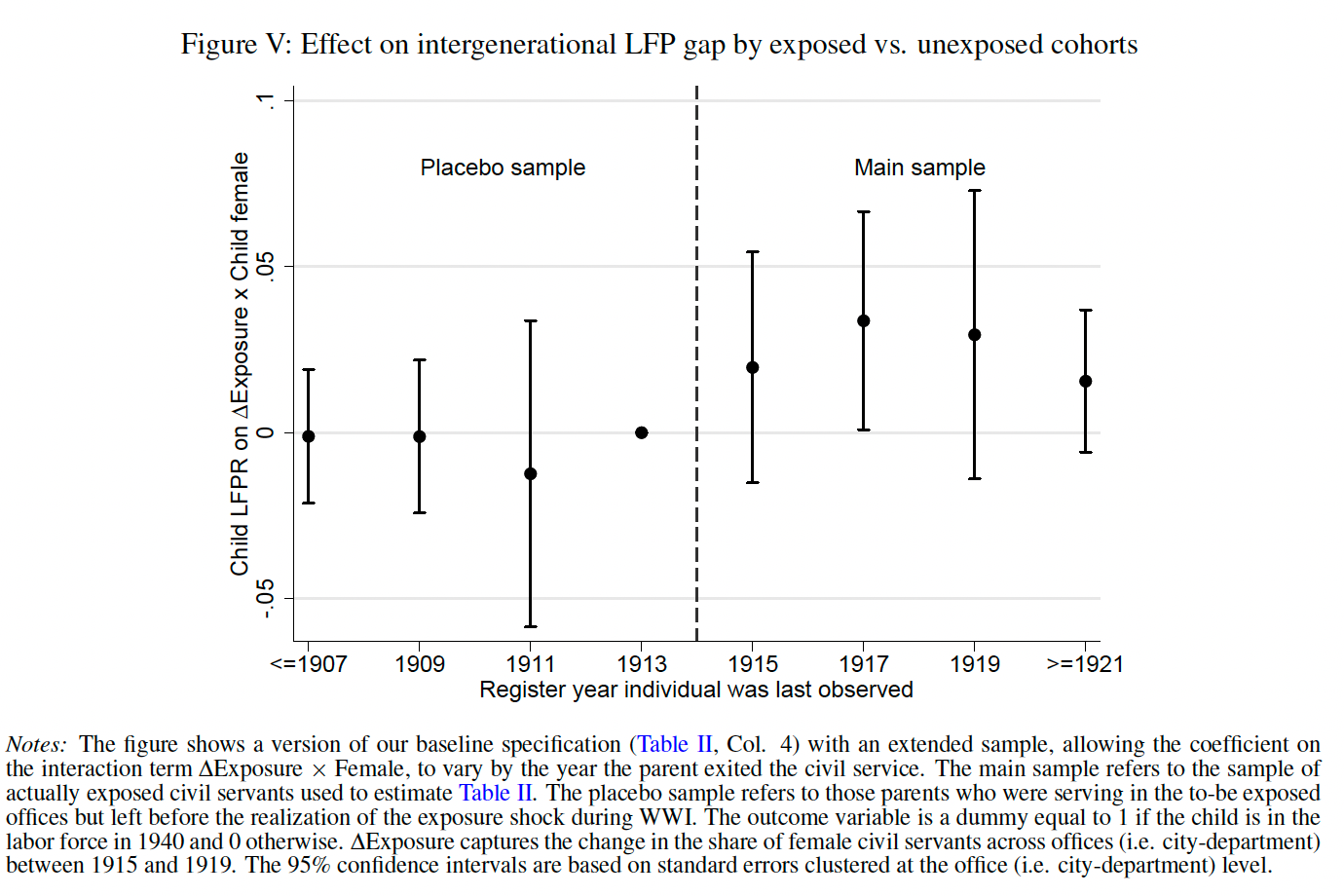

(Sometimes the overlapping confidence intervals make it difficult to know the strength of these heterogenous effects across various dimensions, but this is expected as authors drill their sample down further, exploiting variation in their wonderful dataset!)

Aneja, Farina, and Xu also run a rather clever placebo test to show that actual parental exposure drives results (rather than women selecting into female-friendly offices). They find that the intergenerational effects only hold for those civil servants who left after being exposed to the shock.

Marriage markets!

Marriage markets are an important signal of men’s attitudes towards female talent. Do they want dutiful dependents, who’ll lovingly prepare dinner on arrival, or do they want independent minds, who are making it on their own? In Delhi, employed women are significantly less likely to attract matrimonial offers.

Don Draper, we may recall, didn’t just champion equality in the boardroom, he also mixed things up in the bedroom. Betty (his first wife) stayed at home, Megan (his second) pursued a career. So, one wonders, what happened after the wartime shock?

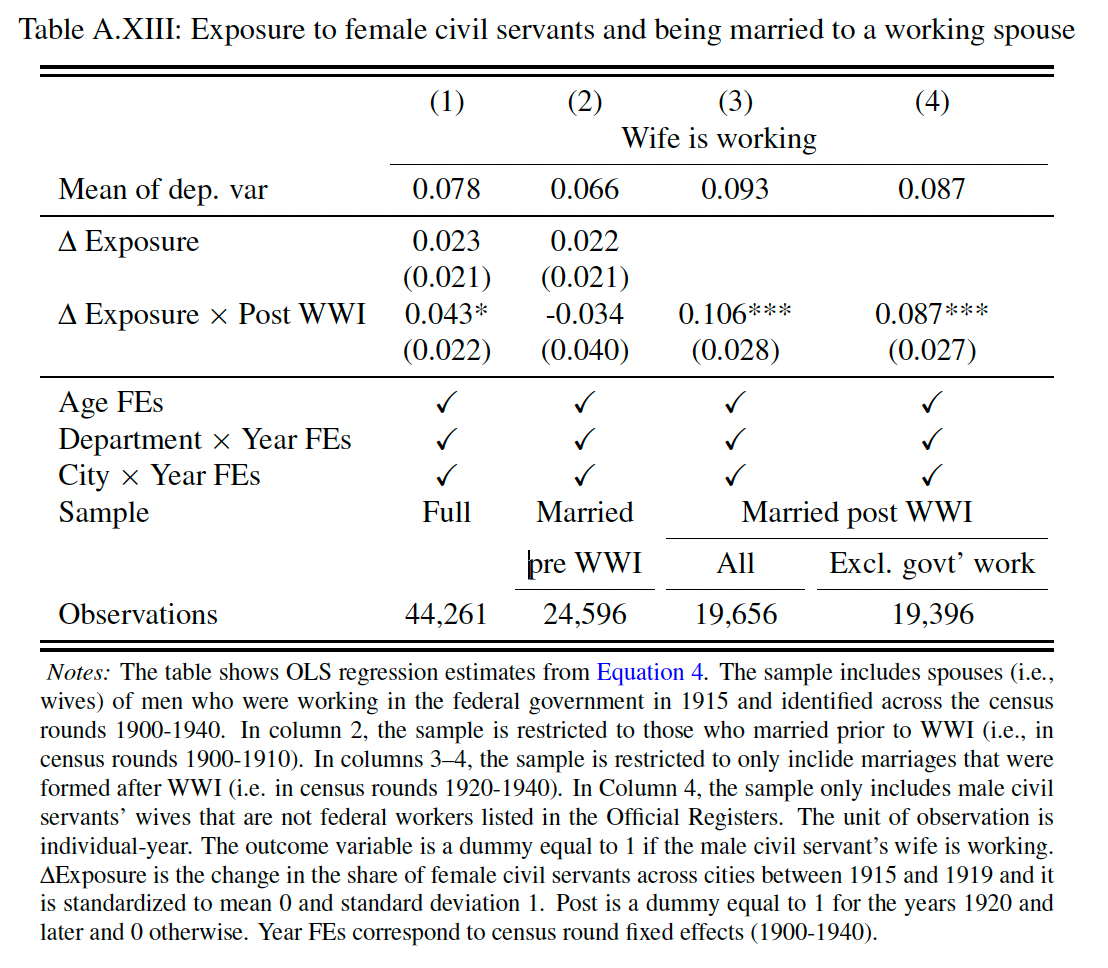

Men with female colleagues were more likely to marry working women

Aneja, Farina, and Xu find that,

Male civil servants who were exposed to more female co-workers during WWI were more likely to marry women who worked outside the home.

A one standard deviation increase in exposure to female co-workers increased the probability of a male civil servant's wife working by 4.3 percentage points after WWI.

This effect was driven by marriages formed after the actual exposure to female co-workers. There was no effect for marriages that occurred before WWI.

The effect was not limited to government work. Exposed men were more likely to marry women who worked in the private sector.

The authors found no evidence that this effect was driven by a decline in the economic status of exposed male civil servants due to increased competition.

Civil servants with women colleagues were more likely to have working daughters

Daughters of more exposed civil servants were more likely to be single and have fewer children in 1940.

But that is not the sole driver of daughters’ increased labour market commitment. Even after the authors include fixed effects for marriage and fertility, daughters of men with female colleagues are still more likely to work.

The effects were not limited to government jobs - exposed daughters were more likely to work in both public and private sectors.

A standard deviation increase in parental exposure closed the gender pay gap by 10%, suggesting daughters entered higher-paying positions.

Effects were stronger when fathers (vs mothers) were exposed to female coworkers (probably due to the paucity of women working in 1917).

Place-based Effects!

Cities with greater increases in female civil servants saw persistent increases in overall female labor force participation through 1940.

There was no comparable effect on male labour force participation - so this is not just picking up a local labour demand shock.

Private sector employment of women also increased.

Gains were concentrated in neighbourhoods where female wartime civil servants resided, consistent with social learning as a mechanism for norm transmission.

The authors (roughly) estimate that each additional female wartime civil servant led to 2.2 additional women entering the workforce. DANG.

THIS PAPER IS TREMENDOUS!!!

Prior research on families has generally focused on mothers. In France, West Germany, Switzerland, Greece, Zambia and Mexico, sons of working mothers tend to be more egalitarian and have working wives. But that leaves an open question how do men come to want working wives? What explains the Don Draper trajectory?

Aneja, Farina and Xu show that after US government departments and cities heavily recruited many women, their workforce participation became more normal, and men’s preferences changed. They increasingly married and fathered working women.

Now, like any journal editor, you may be wondering…

Do these findings have wider validity…?

Through my globally comparative research, I’ve learnt that reactions to women’s encroachments are mediated by prior culture. Compare Zambia, Cambodia and Egypt.

In the 1970s, men on the Zambian Copperbelt were revered as breadwinners, while women were dismissed as housewives, ‘ukwikala fye’ (just sitting). While a few women made in-roads into male-dominated domains, they were routinely derided as ‘prostitutes’ (advancing through sexual favours). But today, Zambians commonly say ‘Banamayo kuti babomba incito sha baume’ – women can do what men can do’.

What led to this change?

Keen to uncover the drivers, I undertook 18 months of ethnographic research in Zambia, conducting hundreds of life history interviews, listening to people’s life experiences and changing ideologies. Piecing this evidence together, I learnt that worsening economic security (the falling price of copper, HIV/AIDS, and neoliberal reforms) had propelled women into the workforce. Seeing masses of women providing for their families, others came to recognise their equal competence. Men increasingly championed gender equality.

Cambodia’s industrialisation and urbanisation is also catalysing growing support for gender equality. In Phnom Penh, male migrants detailed how they had come to reject traditional mantras of inequality after seeing thousands of women demonstrate their equal prowess. Modern men want working wives.

Gender Quotas to the Rescue?

Encouraged by these case studies, one might infer that gender quotas would help normalise female employment in otherwise patriarchal bureaucracies?

Not so fast.

Mid-century Arab modernisers, like Nasser, similarly spearheaded female civil servants, but this actually triggered religious backlash. Writing from schools, universities and government offices, men wrote into Islamist magazines, describing their extreme discomfort with female encroachment. Men’s honour was contingent on female seclusion and many successful organised in resistance.

Culture Matters!

Prior culture mediates how communities react to an exogenous increase in female employment. Never idealising seclusion, US was predisposed for feminist victory.

Bravo to Abhay Aneja, Silvia Farina, and Guo Xu for an absolute masterpiece - my favourite paper of 2024. And I strongly encourage other social scientists to explore what I call ‘the Don Draper trajectory’:

How do men come to value female talent?

My papers on social change in Zambia and Cambodia:

History lessons for gender equality from the Zambian Copperbelt, 1900–1990

‘For the Elections, We Want Women!’: Closing the Gender Gap in Zambian Politics

How Cities Erode Gender Inequality: A New Theory and Evidence from Cambodia

Outstanding article, and it got me thinking if this also partially explains the difference in the perception of women (and feminism) in North America between college educated professionals and the non-college educated working class (very broad over-generalizations but it’s a comment not an academic paper)?

My observation has been that even though white collar professional jobs do tend to have gender segregation by role and department, overall the firm has rough parity between genders (there is even a joke that when a man of the software engineering tribe wants to find a mate he goes to a marketing tribe event).

Whereas my impression (which could be wrong) is that gender segregation for non-college educated working class employment happens more at the firm level vs the department level.

For example, almost all plumbers, electricians, and carpenters are men, and the firms they work at are usually not large administrative operations, so at the firm level it’s almost all men with a small layer of administration often done by women.

On the flip side, almost all of the low wage care jobs (child care worker, elder care, etc). Are held by women, and at the firm level this also appears to hold true.

I guess this is a rambling way of saying that your article sparked these thoughts, so thank you!

Well done drama that it was, I could barely watch the male/female interactions in Madmen.