Modern Threats and Religious Backlash

The Ten Commandments must now be displayed in all Louisiana’s public school classrooms. The law, signed by Republican Governor Jeff Landry, requires poster-sized copies with easily readable text. Christian conservative schools are simultaineously seeing rising enrolment.

Why is this happening? Is it unprecedented?

Actually, it echoes the 1970s global religious revival. Threatened by liberal modernity, conservatives worldwide leveraged new technologies and defensively mobilised to institutionalise piety.

In this essay, I draw on my comparative research to highlight parallel trends in Uzbekistan, Kyrygzstan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Malaysia and the U.S.

Progressive US Laws Trigger Backlash

Brian Wheaton finds that when US states passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) - guaranteeing equal rights - men became more sexist. After a state passed an ERA, the share of men expressing support for gender equality dropped by 15 percentage points. This effect persists over decades. Voters also swung right, favouring Republicans.

In states that passed the Equal Rights Amendment, men were more likely to express dislike of women’s liberation activists.

ALL these laws induced backlash:

Civil Rights Acts

Abortion legalisation

Gun control relaxation

Defence of Marriage Acts

Marijuana legalisation

Gay Marriage legalisation.

Liberal media also posed a threat, catalysing conservative organising to protect America’s moral integrity

The National Council of Catholic Bishops’ protested against the Maude episode on abortion. The National Federation for Decency collaborated with the Moral Majority to become “The Coalition for Better Television”.

.Julian Zelizer and Kevin Kruse see 1970s television as exacerbating America’s internal divisions. I strongly recommend their excellent book, “Fault Lines”.

Randall Balmer similarly makes the case that after the IRS came after racially discriminatory education (Bob Jones University), evangelicals coalesced to form the Moral Majority and vote for Republicans. Under attack, they mobilised in defence.

Cities Can Catalyse Gender Equality

The nexus of schools, job opportunities, and the high-cost of urban living may all encourage female employment. Diversity is also immensely disruptive: by encountering and learning from heterogeneous others, as well as new global media, people may come to rethink old traditions. Cities can thus be transformative.

On cities as catalysts of social change, see my papers, drawing on 21 months of urban-rural fieldwork in Zambia and Cambodia.

However, I now realise that these effects are deeply contingent on prior culture. Neither Zambians nor Cambodians ever idealised female seclusion, thus there was relatively little resistance to them stepping out in public.

Modernisation and Counter-Mobilisation in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia

In the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia, men’s honour had long depended on female seclusion. But this was contested: Arab modernisers wanted reform. In Egypt, Nasser had championed a project of secular, socialist modernisation, incorporating women into the public sphere.

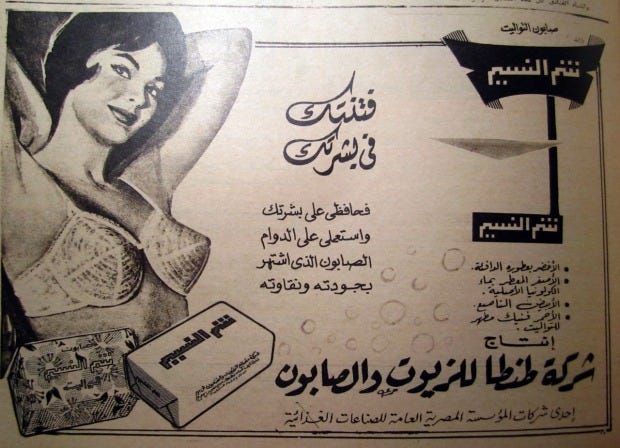

Mass education and urbanisation then created an unprecedented moral challenge: girls and women increasingly interacted with unrelated men. Female education and employment was deeply triggering - they were encroaching on men’s turf. Media fanned the flames: in Cairo and Alexandria, advertisers were marketing soap with semi-naked models. Pious Muslims were alarmed, it created a recipe for fitna (disorder, chaos, corruption).

Threatened, Arab Islamists organised to enforce gender segregation and veiling. Since the Quran is revered as the highest form of knowledge, it was cited to justify proper piety. Here, I draw on two tremendous books by Aaron Rock-Singer:

By studying Islamic media from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, Rock-Singer then traces the emergence of the Islamist and Salafi movements. He shows how modernisation presented both a moral challenge and new technological opportunities Alarmed by moral threats, Islamist and Salafi scholars harnessed new technological innovations - radio, cassettes and periodicals - for mass mobilisation.

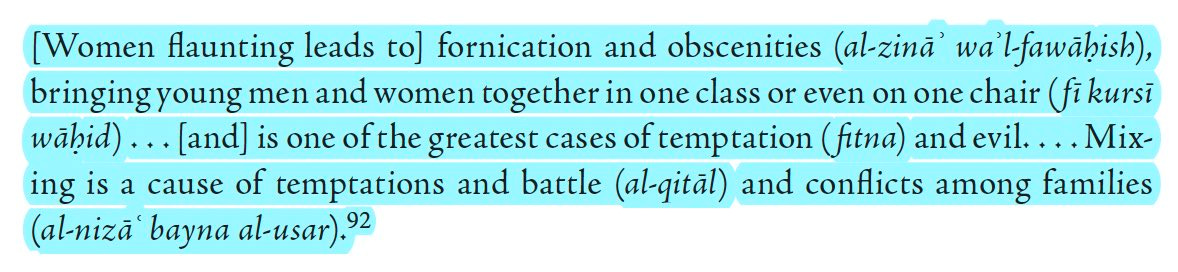

As early as 1933, the Muslim Brotherhood’s magazine al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun warned of the dangers of gender mixing. al-Sayyid Sabiq (an Egyptian Muslim scholar) foretold that female flaunting would lead to the “corruption of morals and destruction of norms of comportment”. A 1958 issue of al-Iʿtisam expresses concern with the “absolute chaos” of women in Egyptian schools and institutes.

In her 1951 book “Flaunting”, Niʿmat Sidqi (a leading female Islamist) criticised Egyptian women for exposing themselves, ‘flaunting’ their flesh, creating a ‘sea of forbidden pleasure’. She called upon Muslims to ‘boycott those who have transgressed proper norms of comportment and modesty’.

Schools were a crucial battleground

Some religious magazines included letters to the editor and fatwa requests - revealing heartfelt concerns about gender mixing in schools, universities and government offices. Many expressed concerns about ‘evil actions’ and ‘illicit looking’.

Back in the 1970s, Islamic magazines were awash with student complaints about moral disorder, insufficient piety, and even religious repression. One student was beaten for quoting from the Quran, another said that religious wall fliers were prohibited, a third said that there were co-ed dances on school grounds. Eager to perform their religious obligations, writers and editors mobilised for schools to institutionalise the ‘zuhr’ early afternoon prayers.

In 1976, Egypt’s Islamist magazine (al-Da’wa) lamented that Quranic knowledge didn’t count towards final grades. The very next year, Sadat’s government made religious instruction a core component of both primary and secondary education, which would count towards students’ overall average. Editors further campaigns for exclusion of non-Islamic materials, which could create corruption (‘fitna’):

Secular legislation and geopolitical maneouvers were also threatening. Islamists became riled when the Government legislated that a woman could divorce her husband if he married a second wife, and when the State Mufti authorised the Camp David Accords. Their values were threatened.

In Kuwait, the Muslim Brotherhood published a weekly magazine called Al-Mujtama - full of articles about the threat of gender mixing. In 1967, parliament passed a law to prohibit gender mixing at university.

Saudi Arabia was also in flux: a flood of foreigners were coming to build up the oil industry, while female education was rising. A Saudi Salafi scholar explained,

The Islamic University of Madina’s flagship journal published an article on “The Danger of Women Joining Men in Their Workplaces”. “The best Hijab for a woman… is her home”, explained Ibn Baz. Like other Salafists and Islamists, he invoked scripture:

Interpretation of scripture has always been contested. Other theologians accepted that women should not flaunt, but that did also entail zero mixing? The Government of Saudi Arabia ultimately decided to institutionalise gender segregation - in schools and workplaces. Since the mullahs were already in power, they could harness the state.

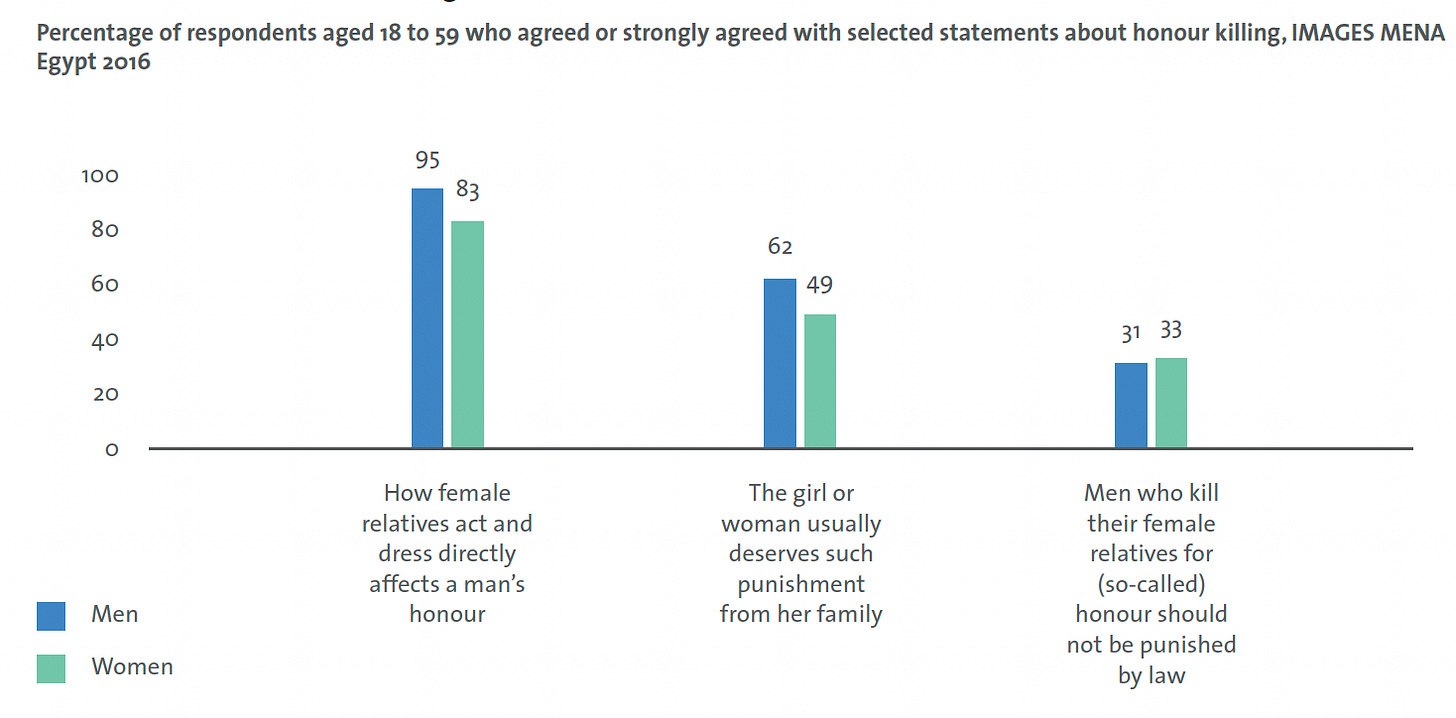

In Egypt, secularists and Islamists continued to battle. Struggling rulers cloaked themselves in religious reforms to gain legitimacy from a pious public, while simultaneously incarcerating dissidents. The Muslim Brotherhood was repeatedly banned and its members were imprisoned. Yet dedicated activists continued to mobilise - leveraging new technologies of mass communication, commanding right and forbidding wrong. Ultimately, they gained wider support. Veiling became normative and female employment remains extremely low.

When people’s deeply-held values are threatened, they mobilise in defence.

In Samarkand, elderly women detailed that as young girls they stayed behind an internal wall, never meeting male guests, or else wore the ‘paranji’ (full body covering). When the Soviets encouraged unveiling, this too triggered a counter-reaction. 2000 women were killed - often by their own relatives. Further resistance was muted, but only because the Soviets institutionalised a violent totalitarian dictatorship.

Fast-forward another hundred years and Muslims still face persecution in Central Asia. Kathleeen Collins argues that this is causing violent extremism.

Modernisation thus generates both moral threats and opportunities for mass mobilisation

Louisiana’s stipulation of the Ten Commandments is thus not so unusual. When people’s central beliefs are attacked, they often mobilise in defence.

Schools were crucial battlegrounds, as competing sides seek to institutionalise their values. To gain legitimacy with an increasingly pious public, leaders adopted Islamising reforms to education. From the mid-1970s, Indonesian students’ class performance in religious instruction counted towards their GPA and college acceptance. Concerted mobilisation enabled the same in Egypt.

The Muslim world was unique in 3 respects:

In the Arab heartland, male honour depended on female seclusion. So the threat of urbanisation and female education generated extensive fatwas against gender mixing.

“Commanding right and forbidding wrong” became a central tenet of Islam, as detailed by Michael Cook.

The 1973 oil crisis delivered an asymmetric price shock, impoverishing oil consumers while enriching producers. Saudi Arabia could increasingly attract impoverished labourers and fund Salafist education, propagating an ideology that reinforced patriarchal status.

As transnational communications and education infrastructure improved, Muslims in distant lands of Malaysia, Indonesia and Uzbekistan could increasingly learn from Mecca. They too came to champion veiling, segregation, religious instruction, and sharia. In the 1970s, Malaysian factory workers campaigned for the right to ‘zuhr’ prayers.

That did not happen in Cambodia and Zambia, because they never idealised female seclusion, never identified as Muslim, and and never received Saudi funding.

Democratisation enabled Islamists to campaign:

Under religious repression, Islamists were heavily restricted. As soon as Islamists could campaign openly, they leveraged new technologies and mobilised the masses. Following the Arab Spring, Islamists won 70% of seats in the Egyptian parliament.

After thousands marched against a Chinese Christian Governor of Jakarta, Indonesian Muslims realised widespread opposition and became more critical of non-Muslim leaders.

When Kyrgyzstan liberalised in the 1990s, religosity surged. More Kyrgyz identified as Muslims, fasted, attended Mosques, made the hajj, and studied the Qur’an. Madrasa enrolments increased by over 3,300 students every year. More mosques than schools have been constructed since 1991. Alcohol consumption and mixed sex intermingling in weddings declined. Multiple civic organisations pressed for more Islamic influence, education and laws.

In prosperous Malaysia, young Muslims are eager to improve and enforce scripture, typically express strong religosity and lately voted for Islamists.

Contrary to Modernisation Theory, economic development does not necessarily entail cultural liberalisation. Instead, it may fuel backlash. New technologies can also be harnessed to serve goals of social conservatism - especially in democracies.

Upcoming Episode of Rocking Our Priors

My next guest is Aaron Rock-Singer, we will discuss his brilliant books. Stay tuned!

Obviously a big difference is that the US currently has a secular and liberal majority, while these Islamic countries have never had that. The Arab modernizers were a small elite. Even when the US had a conservative majority by today's standards, that majority was never close to being as conservative as most Muslim countries, because as you say, Muslims had and still have a tradition of idealizing female seclusion and gender segregation, while Westerners have never had such a tradition in modern times.

That progressive legislation causes backlash is not unexpected, but the difference between the US and Muslim countries is that in the US this backlash has been overcome. You can look at polls, and see how US public opinion has gradually become more progressive over the decades, despite momentary setbacks. Today in the US, many Republicans have to pretend not to be in favor of abortion bans in order not to suffer electoral losses, and other social changes have been even more radical.

The question then is, why do liberal elites succeed in the West but not in the Muslim world? It probably has something to do with WEIRD populations being predisposed to think differently about individuals and their communal obligations. Perhaps interesting is to see where liberal elites are succeeding outside of the West, in places like East Asia and Latin America, and perhaps the answer to that is that these places are just Westernized or Western influenced.

"Gun control relaxation" - you coded this as a progressive reform of the 60s or 70s. And one that caused a backlash.

What are you trying to suggest happened, how was it perceived as progressive, and who was reacting against it?

Was it: a) were being made *easier to obtain* by all? -which is what relaxation sounds like, and although in 21st century America, this is a right-wing, conservative coded position, in the 60s-70s it was left-wing?

b) Guns were made harder obtain by all? And this was immediately considered a left-wing position, and immediately opposed by right-wing backlash (as in the 21st century)

c) States set up a more uniform standard for *all citizens* to obtain guns, white *and* black, male *and* female, old *and* young? This was considered a progressive reform at the time and a previous, more blatantly discriminatory system allowing guns freely to "members of society in good standing" - white, non-dissident men, and keeping them out of the hands of "the wrong kind of people" - non-whites, the young, women, dissidents, was preferred by traditionalists so they did not like reforms?