Can Big Data reveal how Egypt - repeatedly - become so Patriarchal?

Ancient Egypt was relatively gender equal. Women enjoyed legal equality, could act as witnesses, own property, receive an equal inheritance, initiate divorce and keep their assets. Today, Egypt is extremely patriarchal. Only 16% of women are in the labour force. 90% of men say that ‘a woman should tolerate violence to keep the family together’. 53% of Egyptian men think a woman may deserve to be beaten.

How did a gender equal civilisation become so patriarchal?

To answer this question, I have traced five thousand years of cultural evolution. By analysing thousands of statues, paintings, tapestries, street photos, magazines, and advertisements, and drawing on brilliant research by historians, anthropologists, economists, and political scientists, we can identify the drivers of patriarchy.

Change is by no means linear. You may find my findings surprising, perhaps even shocking. Egypt actually transitioned from equality to inequality not once, but twice.

3rd Millennium BC

A limestone statue of an unidentified woman (4th Dynasty, 2613 to 2494 BC). Nude, with no indication of modesty.

The stele of Itetioqer, his wife and two daughters. There is no indication of honouring a male lineage or male relatives. The family is remarkably nuclear. 2123-2040 BC

2nd Millennium BC

Female musicians often performed at religious rituals, festivals, banquets, military and funerary processions. This train of female singers decorates the tomb of Queen Nefru. Each woman wears a long wig, a white sheath dress. (2049 BC - 1998 BC)

Nude female acrobat, performing a funerary dance (the Khetebt). 1938-1630 BCE.

An elite young woman in a linen dress holds a lotus flower (symbolising rebirth). 1500-1450 BC. No indication of modesty.

Sekhmet was the Egyptian goddess of destruction. Represented as a lioness-headed woman; her name means 'she who is powerful'. Black granite statues. 18th dynasty (1550- 1292 BC)

Hatshepsut initially ruled as regent then became the fifth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (1479-1458 BC).

She was not alone. In Ancient Egypt, women comprised 20% of the elites - far higher than Mesopotamia, Greece, Persia and Rome.

Henuttway (also called the Chantress of Amun) decorates almost every scene in her husband’s tomb. He ( Menna, 1420–1411 BCE) is thought to have been a scribe and manager of fields belonging to the fields, as well as the temple of Amun-Re. Her transparent dress sharply departs from contemporary ideals of protective jealousy.

This feast was held in honour of an official called Nebamun. The top left panel shows married couples sitting in pairs - indicating respect for the marital bond (rather than all-male socialising).

On the top right, young women sit and chat together.

The bottom left depicts naked serving girls. 1370 BC.

A high-status "Lady of the House” (a title for married women), 13th century BCE. An exposed belly button indicates scant concern for modesty.

Chantress Nehy sits on a chair and holding a rattle, as part of her professional role in worshipping the goddess Hathor. 1250-1230 BC

Herihor was the High Priest of Amun at Themes, Herihor, and effective ruler of Upper Egypt. His wife Nedjmet was a noblewoman. Here, they are making offerings to Osiris, Isis and Horus’ four sons. 1077 BC to 943 BC

1st Millennium BC

This panel shows the priest Amenemope and his wife Taditkhonsu. Their daughter (‘the lady of the house’, Mutemperes) crouches before them, in a gesture of mourning. A priest is on the left. No male relatives are present, indicating recognition of the nuclear family. Indeed, kinship was bilateral, recognising both male and female descent. 9th century BC

Persian Conquest, 525 BC

Achaemenid Persians ruled Egypt from 525-404 BC.

Two female musicians (380-343 BC): one beats a drum, the other plucks a lyre and dances.

Greek Conquest, 322 BC

In 322 BC, Alexander the Great invaded and conquered Egypt. In “Women and Gender in Islam” Leila Ahmed states that women’s status deteriorated under Greco-Roman rule. Has this been confirmed by subsequent research?

Well, the Ancient Greeks were certainly patriarchal. Mortal women were veiled, secluded and denied any rights. Ancient Greeks also worshipped virgin goddesses (Artemis and Vesta) - reflecting stronger concerns for chastity.

In the first few centuries, the state upheld both Greek and Egyptian law. Egyptian women could appeal to their own law and act without a male guardian. Foreign immigrants sometimes adopted Egyptian identities to benefit from Egypt’s gender equal law!

However, subjugated Egyptians sometimes adopted Greco-Roman practices to gain upward mobility as merchants, landowners, soldiers and bureaucrats. Egyptians started dressing like Greco-Romans, attending plays and going to the public baths. Egyptian women sometimes sought legal guardians so that they might appear like sophisticated Greeks! Rather than autonomy, they privileged prestige.

Once Greek law became hegemonic, women were not allowed to decide any legal or economic matters without a male guardian (kyrios). Mothers with 3 or more children could exercise legal autonomy, but by then they were de facto dependent on a man.

Women lost status, but continued to be publicly portrayed. This painting shows Berenice II (wife of Ptolemy III Euergetes, 246-222 B.C) - unveiled.

This ring is dated to 1st or 2nd century BC. It shows Fortuna, the female personification of good luck

This statue shows the goddess Isis suckling her son Horus. Even in this Ptolemaic period, Egyptian deities were still worshipped.

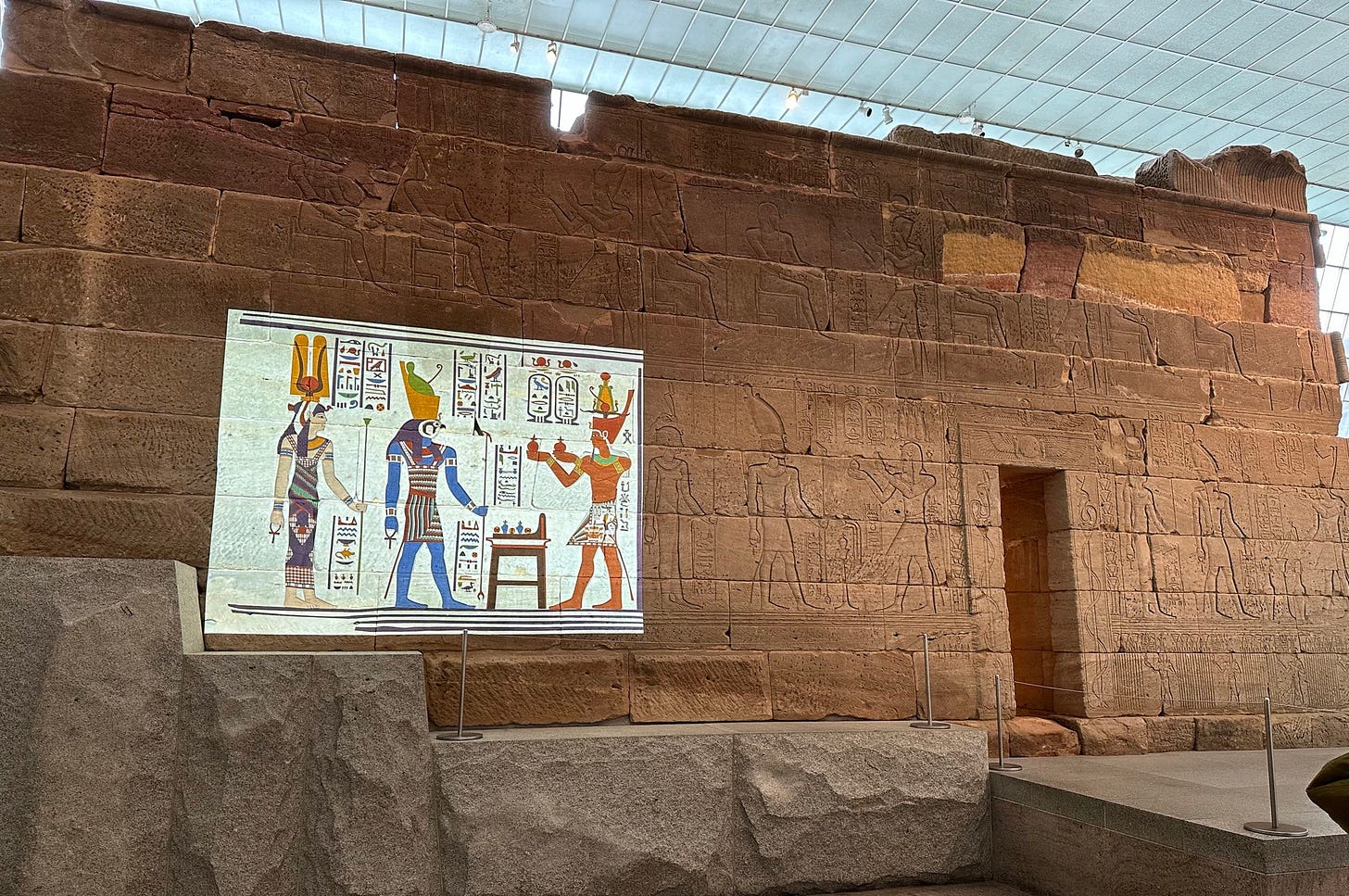

Here you see the king (actually Caesar of Rome) making an offering to Isis. 15 BC (Colorisation via lights). Triangulation is warranted, however. Despite the depiction of Egyptian deities, Demotic (ancient Egyptian script) contracts were radically in decline.

A naked Egyptian woman rides side-saddle on a large pig. 1st C BC.

Roman Conquest, 30 BC - 641 CE

Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. Alexandria was one of the most important cities in the Roman world - renowned for its libraries, temples, science and trade network.

In her wonderful book on Greco-Roman Egypt, Ada Nifosi comes up with several strategies to identify women’s freedoms. She explores the share of documentary papyri that were written by women. Between 1st century BC to 4th century CE, women authored 1%. After the six and seventh centuries ‘women simply disappear’.

Architecture also provides helpful clues. In Greco-Roman Egypt, there were no norms around gender differentiated domestic spaces. Elite families are an exception, unmarried daughters often had rooms on upper floors, to protect their reputations.

But as Robert Tignor details in his excellent history of Egypt, Greek influence should not be overstated. The vast majority of Egyptians remained poor farmers; they did not adopt Greek language, rarely used its laws, and are unlikely to have been influenced by a change in ruling elites.

Women also continued to play major roles in Egyptian monasticism. One of the most influential monastic movements in Upper Egypt, the White Monastery, included 4,000 monks, including 1,800 women.

Wealthy women are shown looking out to the world, uncovered. Portraits were painted during the owner’s life, hung in their home, and then affixed to their mummy after death. This mummy portrait is dated to 1st century CE.

Each of these women appears remarkable strident. This mummy portrait is from 138–92 CE.

This woman (160-225 CE) right at you. She is bold.

This portrait of a young, wealthy woman is dated to 100 CE. Still no veiling.

This portrait of a wealthy woman (intended to cover the face of a mummy) shows a woman looking out at the wider world. 130 C.E. - 161 C.E.

This is a Romano-Egyptian funerary portrait of a woman (175-200 CE). The lines on the neck are called “Venus rings”, and connote the goddess’s sexuality. The jewellery and bright clothing indicate a woman of wealth.

‘Isidora’ (ICIΔOPA) is written in Greek on the mummy’s right upper shoulder. This Romano-Egyptian portrait conveys a woman of substantial wealth - wearing emeralds, amethyst, pearls and gold. Her tightly braided Trajanic hairstyle is secured with a gilded pin. This is dated to around 43 BC – 122 CE.

This portrait of a woman was attached to an Egyptian mummy, but it’s in the Greco-Roman style. They appear to have adopted the Greco-Roman aesthetic style of painting, but not veiling. At odds with ideals of modesty, they wanted to show what she looked like (100-120 CE)

This mummy portrait is from 170-200 CE. Her pearls indicate elite status. She is uncovered and unashamed.

Greek-ruled provinces appear to have been the most patriarchal

We can see this by comparing geographical variation in land ownership and art.

Lower and Middle Egypt were much more heavily influenced by the Greeks. Records for the first century of the Ptolemaic Period (after 332 BCE) suggest land in Lower and Middle Egypt was generally owned by men. Upper Egypt was less culturally and legally Hellenised: women continued to own arable land.

Art also conveys the persistence of Egyptian culture. This mummy portrait from Upper Egypt is clearly not in the Greco-Roman style. It shows Sensaos - the daughter of a high official in the provincial government. She died aged 16, in 109 CE.

In Upper Egypt, there is less Greco-Roman art and more female landownership.

Isis-Aphrodite (2nd century CE). Even after Roman conquests, unveiled women were still on display.

This painted wood panel from a coffin is thought to depict Isis (half naked) being served by a deceased person (undearneath). It’s from 3rd century CE. So even after Greek and Roman conquests, Egyptians did not idealise modesty.

The Byzantine Empire

In 395 CE, the Roman Empire was divided. Egypt became part of the East Roman Empire, which was Christian.

This square wool tapestry shows a woman with her hair tied at the back, 5th-7th century CE

Saint Thecla was revered as the first female martyr. When she refused to renounce her faith, Roman authorities put her to burn at the stake, but she emerged unscathed. Then they threw her to wild animals, who refused to attack. She survived these ordeals and became a healer.

This relief depicts Thecla tethered to a lion and a panther, yet protected from danger by the angels. This is apparently Coptic.

Christianity is thus shown as protecting a woman from danger.

The Virgin Mary is glorified in this 6th century tapestry. Mary is seated on a jewelled throne, alongside the archangels Michael and Gabriel. They are surrounded by the 12 apostles.

Arab Conquests

In 639 CE, Egypt was invaded by Arab armies and became part of the Ummayad Caliphate. Political authority was consolidated under a dictator (caliph), with elite slave soldiers (mamluks), who were compensated with non-hereditary land grants (iqta). Absolutist rule was then legitimised by clerics (ulema).

Clerics legitimised the caliph’s rule to the masses and in exchange the caliph instituted sharia law, which raised the authority of the clerics (as detailed by Jared Rubin, Ahmet Kuru, and Timur Kuran). Religious authoritarianism (with slave soldiers and centralised land grants) persisted right through to the Ottoman empire.

This 10th century Egyptian textile lavishes praise on the Fatimid caliph.

“In the name of Allah the merciful, the compassionate. Victory from Allah to al-Mansur”

Conquered people gained rights and tax exemptions if they converted to Islam, recited the Quran, gained an Arab patron, and adopted tribal lineages. As part of this cultural assimilation, they also adopted tribes and cousin marriage. To this day, cousin marriage remains especially high in Muslim-majority countries that were originally part of the Umayyad Caliphate.

Patrilineal kinship was also cemented by Sharia law, which recognises succession through the male line, male agnates’ inheritance, paternal ownership of children, and easy divorce for men. Paradoxically, patrilineal kinship was also reinforced by the Islamic stipulation of female inheritance rights. Kin marriage kept wealth in the family, while also consolidating fraternal solidarity and shared honour.

Ghazali’s influence on Islamic ethics

From the 8th to 13th century, Iraq was the seat of the Sunni Muslim empire. Persian theologians managed state institutions of learning, and played a crucial role in developing Islamic ethics.

Al-Ghazali (a 12th century Persian theologian) became enormously popular in Egypt. He taught at Cairo’s Nizamiya madrasa and delivered public lectures. His seminal texts (“The Revival of the Religious Sciences” and “The Incoherence of the Philosophers”) became core texts in madrasas and Egypt’s Al-Azhar University. Ghazali’s moral and political philosophy was institutionalised, while dissent was repressed.

Ghazali constructed men as intellectually superior, uniquely capable of reason, and thus rightful patriarchs. Men could only achieve piety by preventing fitna (moral corruption) and policing women. He further denigrated marital love, while lavishing praise on filial piety and male friendships. Men were intellectual equals, who helped cultivate each other’s spiritual refinement. In trust-based societies, where government, commercial, and political networks, all rely on whom you know (‘wasta’ in Arabic), these fraternal ties helped to consolidate men’s advantage.

Ghazali fervently opposed women’s public presence:

“Ghazali… quotes Umar ibn al-Khattab, who said that the Prophet allowed women to go into public back in the days when they used to veil themselves properly, but that if he saw the ways of women today, he would rescind that permission.

Ghazali then states that “there is greater harm to women at public sites and gatherings” than in the past. Here, Ghazali echoes the common argument of the ‘ulama’ lamenting the loss of a golden era when women knew how to conduct themselves in public” (quoted in Zahra Ayubi’s 2019 book “Gendered Morality”)

Clerics repeatedly prescribed gender segregation: barring women from communal prayers in the mosque. 12th century Cairene women did defy these prescriptions (occasionally they even preached). But open dissent was increasingly inhibited by close-knit tribes, fear of eternal damnation, and religious authoritarianism. In the 13th century, Mamluk sultan Barsbary and clerics claimed that Egypt’s famines were Allah’s punishment for women’s unIslamic practices, they were ordered to stay at home.

Additionally, there is no literature written by women from late Medieval Cairo, Damascus or Jerusalem in the Mamluk period (1250-1517).

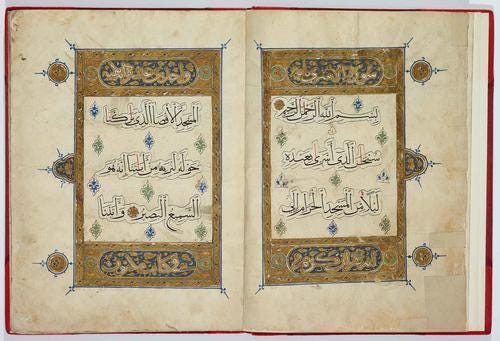

No Portraits

We have very few pictures of this period because image-making is expressly forbidden in the Hadith. This makes it a little harder to understand gender relations.

‘Abdullaah ibn Mas'ood (may Allah be pleased with him) reported that the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) said: “Those who will be most severely punished by Allah on the Day of Resurrection will be the image-makers”. (Reported by al-Bukhari, see al-Fath, 10/382).

‘Ali (may Allah be pleased with him) said: “Shall I not send you on the same mission as the Messenger of Allah (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) sent me? Do not leave any built-up tomb without levelling it, and do not leave any picture in any house without erasing it.”’ (Reported by Muslim and al-Nisaa'i; this is the version narrated by al-Nisaa'i).

Ibn 'Abbaas (may Allah be pleased with him and his father) reported that the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) said: “Every image-maker will be in the Fire, and for every image that he made a soul will be created for him, which will be punished in the Fire.” Ibn 'Abbaas said: “If you must do that, make pictures of trees and other inanimate objects.” (Reported by Muslim, 3/1871).

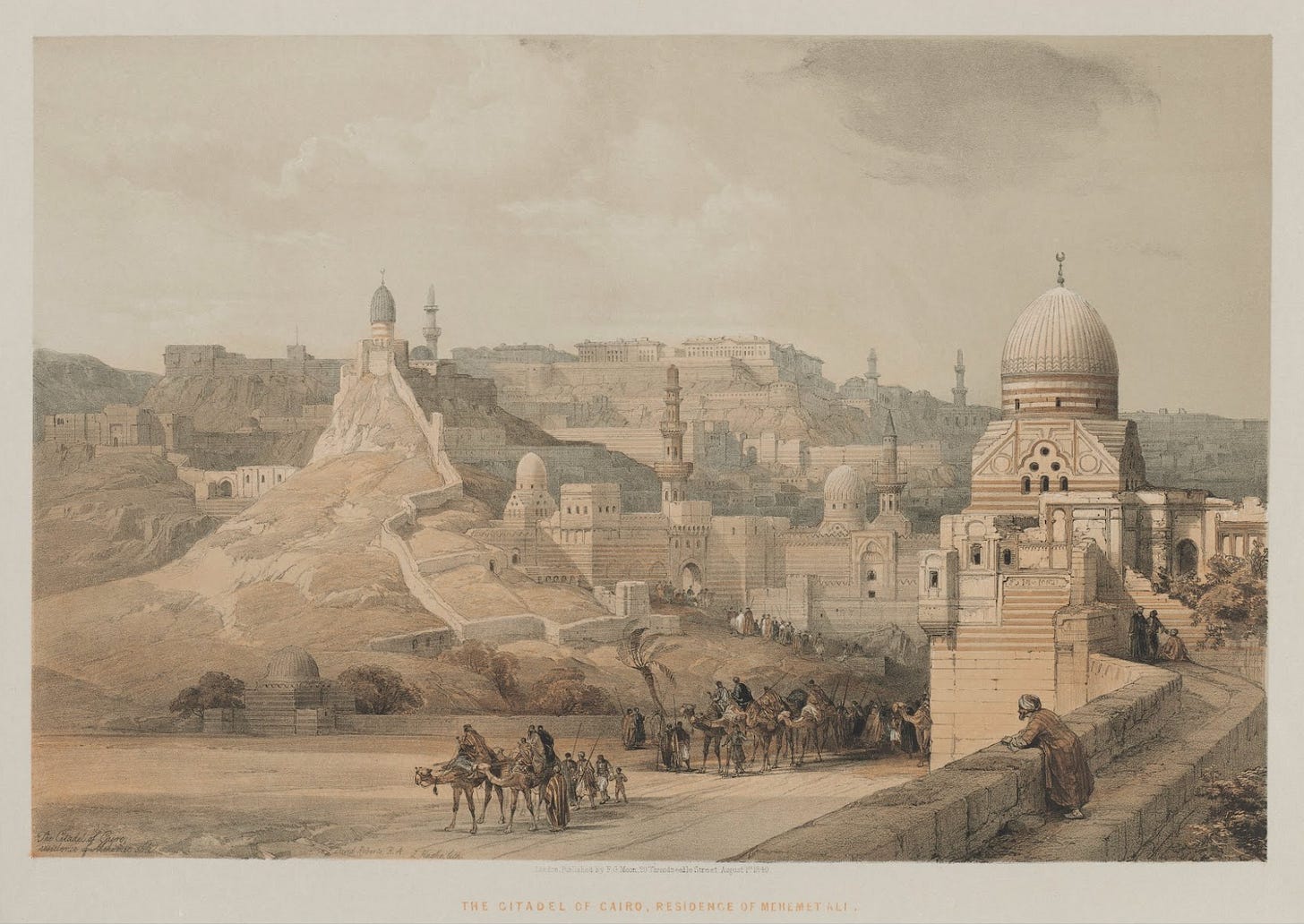

Ottoman Empire (1285 - 1923 CE)

Under the Ottoman empire, there was a strong preference for female seclusion. Honour and commerce within kinship networks was contingent upon eliminating rumours of female impropriety. Clerics and concerned publics repeatedly petitioned the Sultan to crack down on women’s freedoms.

Religious authoritarianism instilled conformity. Military rulers maintained legitimacy by rewarding loyal clerics with waqf income, funding mosques, and madrasas. This alliance between state and clergy inhibited independent critique, thus many families continued to be locked in a culture of deference to clerics, who reinforced female seclusion with warnings of divine punishment.

Ottoman towns tended to be more gender segregated. Hawking in busy city streets meant fraternising with non-kin, fuelling gossip, jeopardising a woman’s honour and thwarting her marriage prospects. Only the poorest, most desperate women peddled food in Cairo. Divorced women who supported their children by trading at the market could even lose custody rights. Behind closed doors, ordinary women worked in textiles: spinning thread and weaving cloth at home. Peasants invariably worked in family fields.

Canny Ottoman women used Islamic courts to advance their interests. Peasant and lower class urban Egyptian women pursued their interests in Islamic courts: trading property and pursuing thieves. 19th Century Egyptian elite women invested in businesses and litigated in court, but intermediaries operated on their behalf while they remained secluded. They were by no means passive.

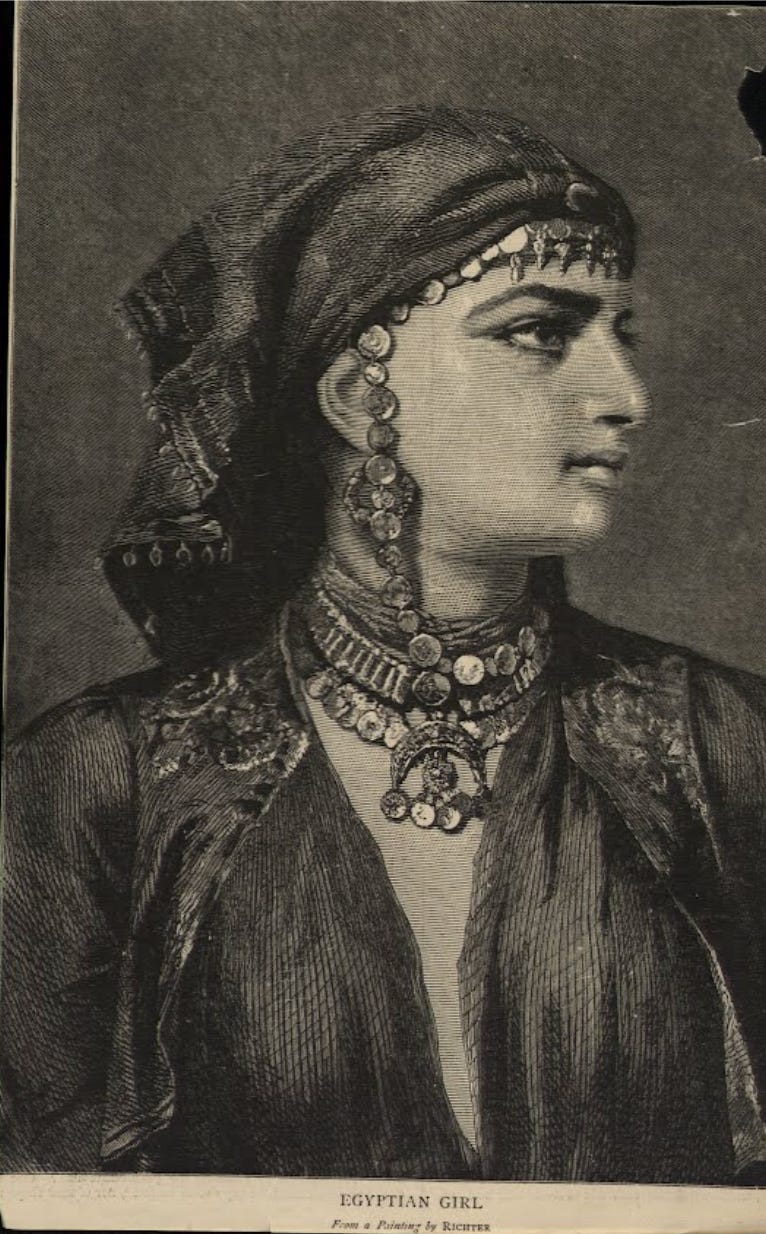

Given Islamic proscriptions on images, most 19th century pictures were created by non-Muslims. Gabriel Lekegian was an Armenian photographer who travelled around Egypt in the 1870s and ‘80s. He depicts women farmers carrying water.

Rural peasant women often covered their faces with a long rectangular piece of cloth.

“The Return of the Mahmal from Mecca to Cairo” (1876) by Konstantin Makowsky is shown below. The Mahmal is a ceremonial palanquin carried on a camel during the Hajj (the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca). All women are veiled, some are looking out from an upper balcony.

Is this depiction accurate? Perhaps female seclusion was exaggerated, to create a sense of Otherness?

Numerous vintage photographs indicate strong ideals of female seclusion.

This is an early 20th century photograph of the Procession of the Mahmal. The street is overwhelmingly male, but veiled women can be seen on the left-hand side upper balcony.

Bedouins

Nomadic Bedouin women of the Sinai wore clothes with embroidered coins - like those shown below.

20th Debates about Islam & Modernity

Confrontation with European modernity provoked elite debates about women’s place in society. As men became more educated, they increasingly valued female education (to create good wives and mothers). Although clerics denounced girls’ schools as un-Islamic, feminists fought back. Publishing journals, women debunked men’s narratives, decried their “imprisonment” and highlighted scriptural support for equality. Egypt spawned ‘nahda’ (rebirth) of Arab thought.

Egypt’s feminist awakening

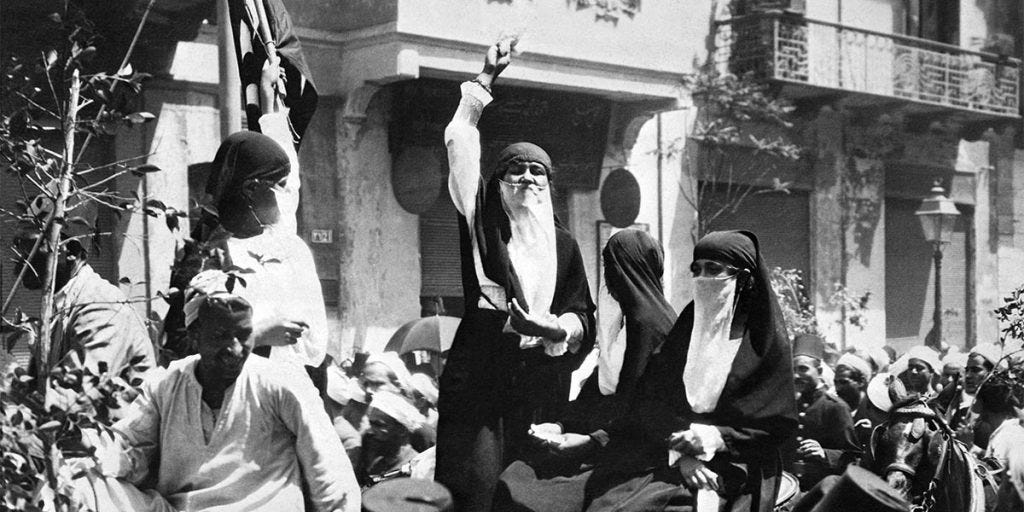

Huda Sha’arawi was born in 1879, the daughter of Mohamed Sultan Pasha (aka the ‘King of Upper Egypt’, for he owned a ginormous estate). Age 13, she was forced to marry her 40 year old cousin. However, she did not move in immediately, and continued her education.

In 1919, Sha'rawi and and other upper class wives organised a protest march - against the British. Following its success, she was invited to a conference in Rome. Returning to Cairo, Sha'rawi and other women publicly unveiled. They continued to organise for women’s rights and freedoms.

“Egypt Awakened” (Nahdat Misr, 1928) by Mahmoud Mukhtar depicts a sphinx of antiquity and a woman raising her veil. Liberals view this as progress; it represents expectations of cultural change.

Wealthy women apparently unveiled upon travelling to Europe:

“You may see a bevy of women arrive at the Cairo railway station shrouded up to the eyes ... The women must not look at any on the platform, far less speak to them; they are locked in their carriage, and conducted from the carriage to the steamer in same way. The next morning the same women appear at the pub meal in the saloon, unveiled, bareheaded, clad in the latest Paris travelling fashion”.

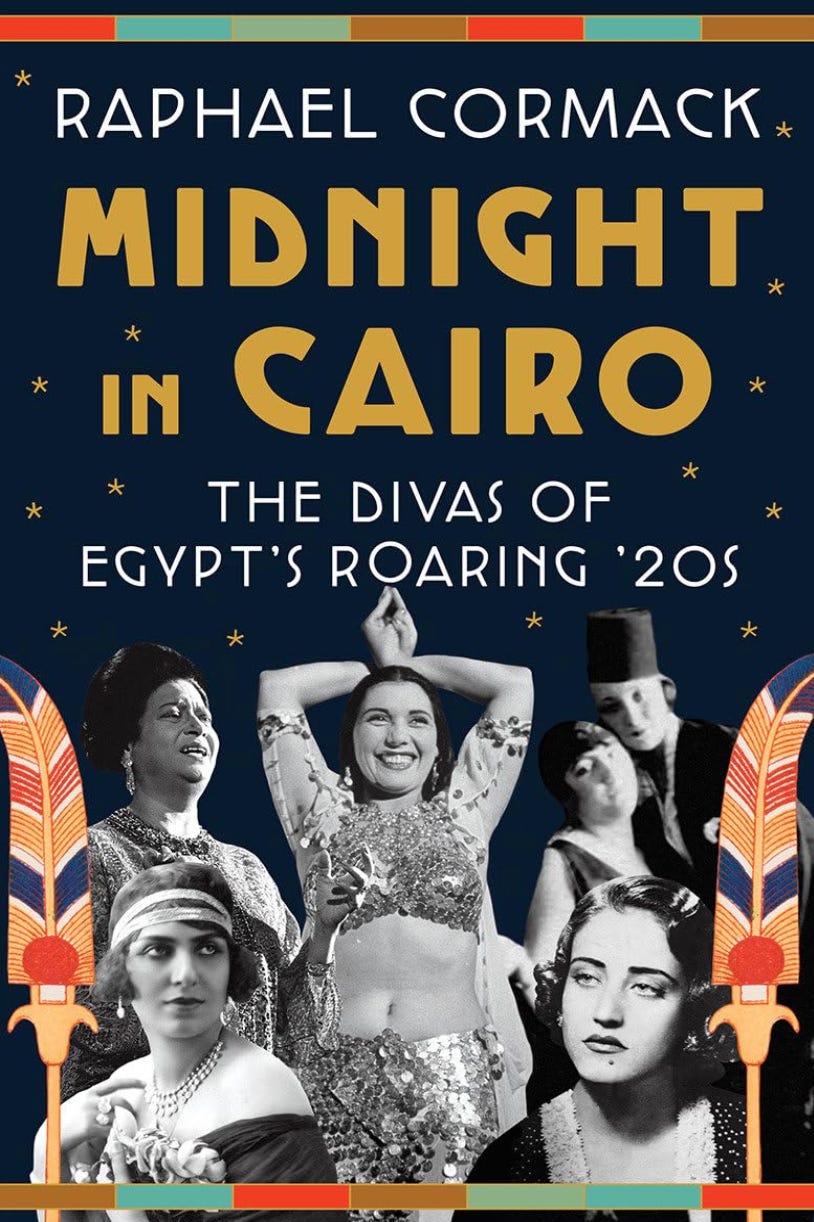

In the roaring ‘20s, subversive, transgressive women brazenly defied patriarchal strictures. As detailed by Raphael Cormack, some women owned dance halls, wrote and directed plays.. Artists in the vanguard.

This family portrait from Cairo 1928 similarly highlights Western style of dress.

However, caution is warranted. While every society may have pockets of underground liberalism, we need to triangulate with everyday street photography.

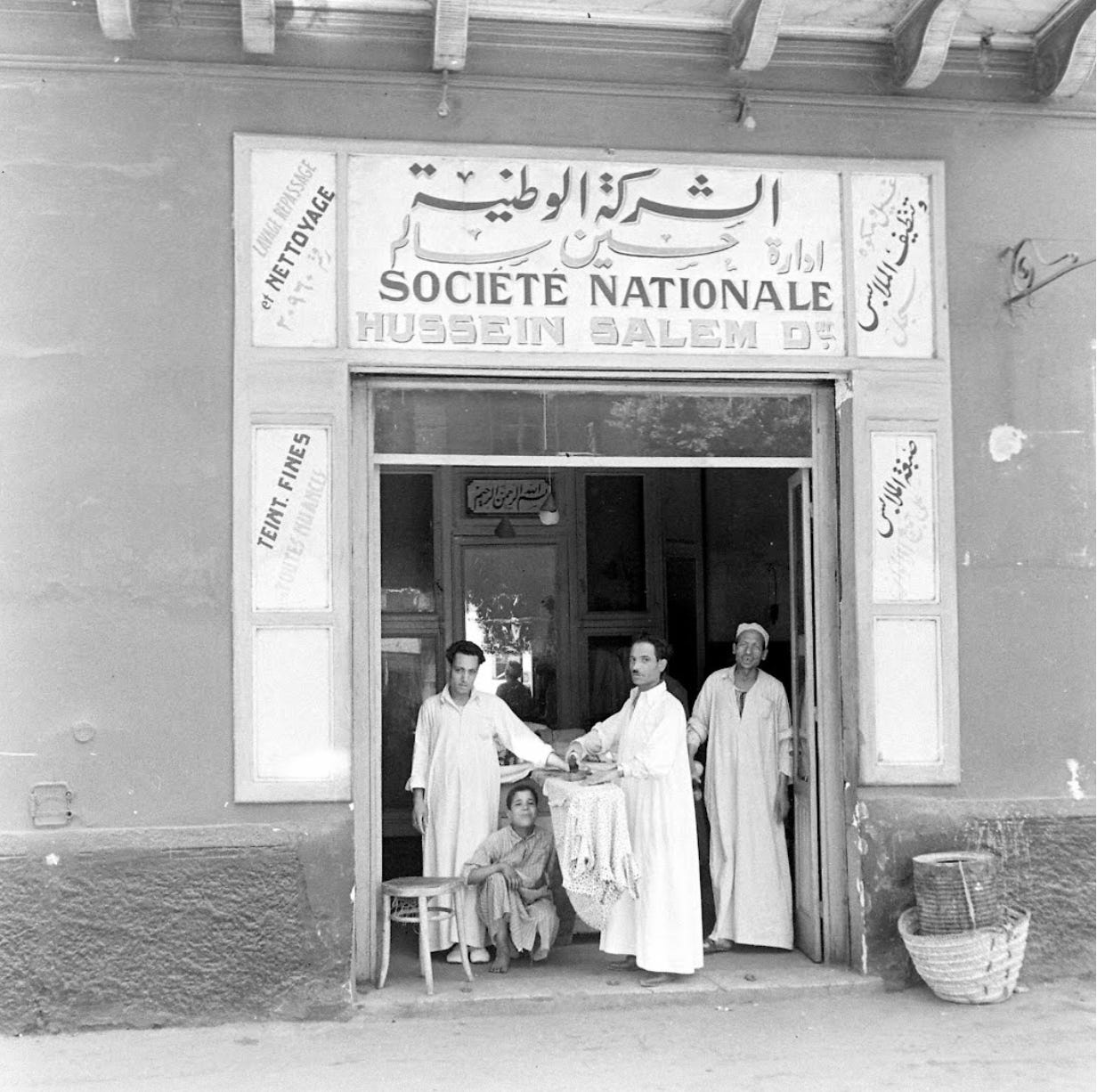

Street Photography in 1930s-1940s Cairo

Street photography suggests that public space continued to dominated by men. When women appear, they are heavily covered. The following photos were all taken by John Phillip and Bob Laundry at Life magazine.

When women appear in 1940s street photography, they are heavily covered.

A large crowd of fully veiled women listens to a preacher for the Egyptian Festival of Spring. 1947

Although the Quran tells believing women to ‘lower their gaze’, this Cairene woman looks directly at the photographer, with total confidence. 1942

The middle class was Westernising

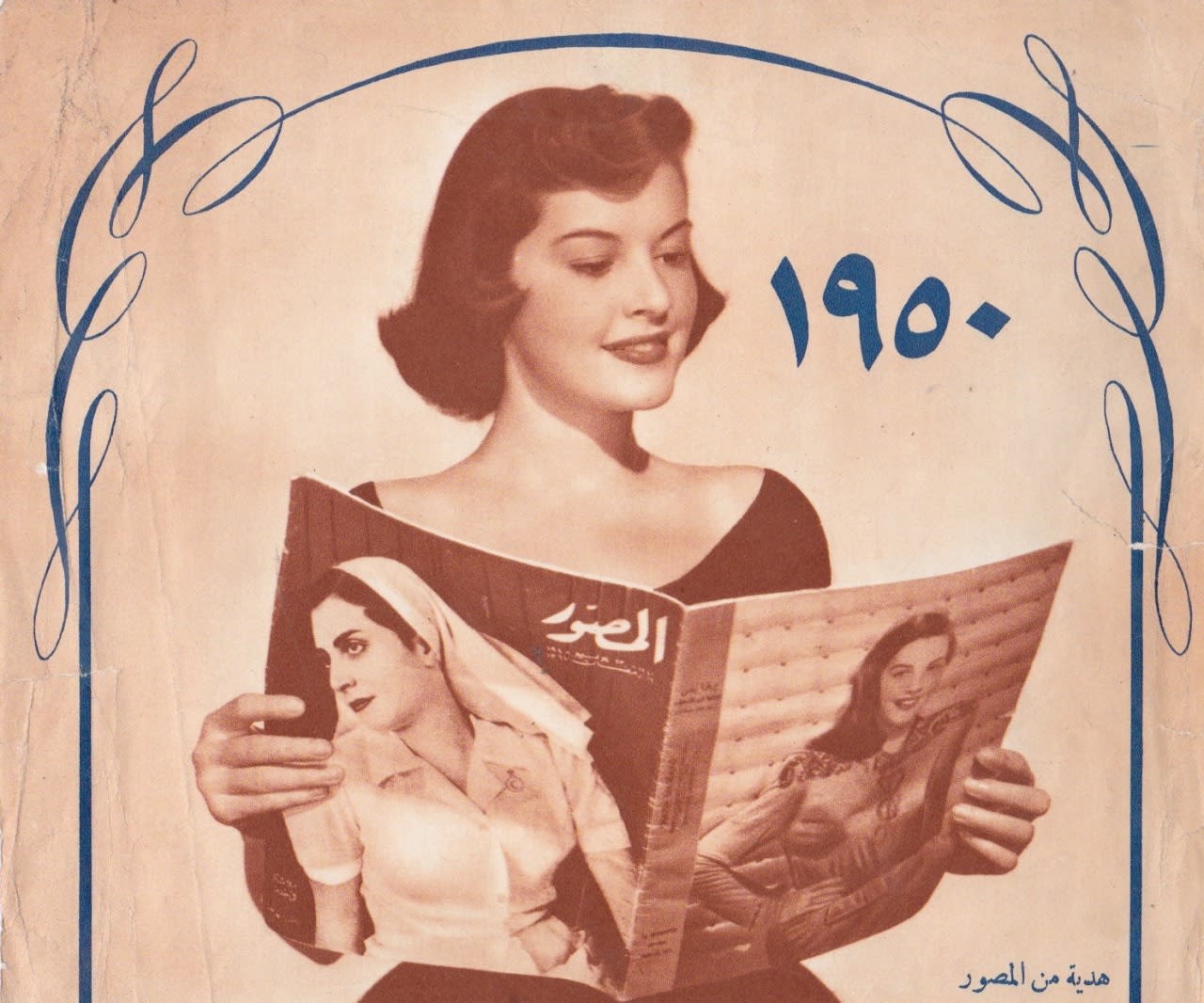

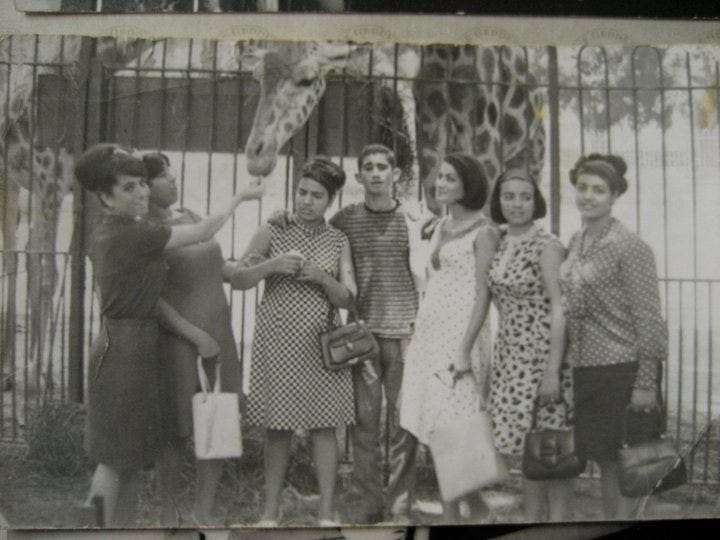

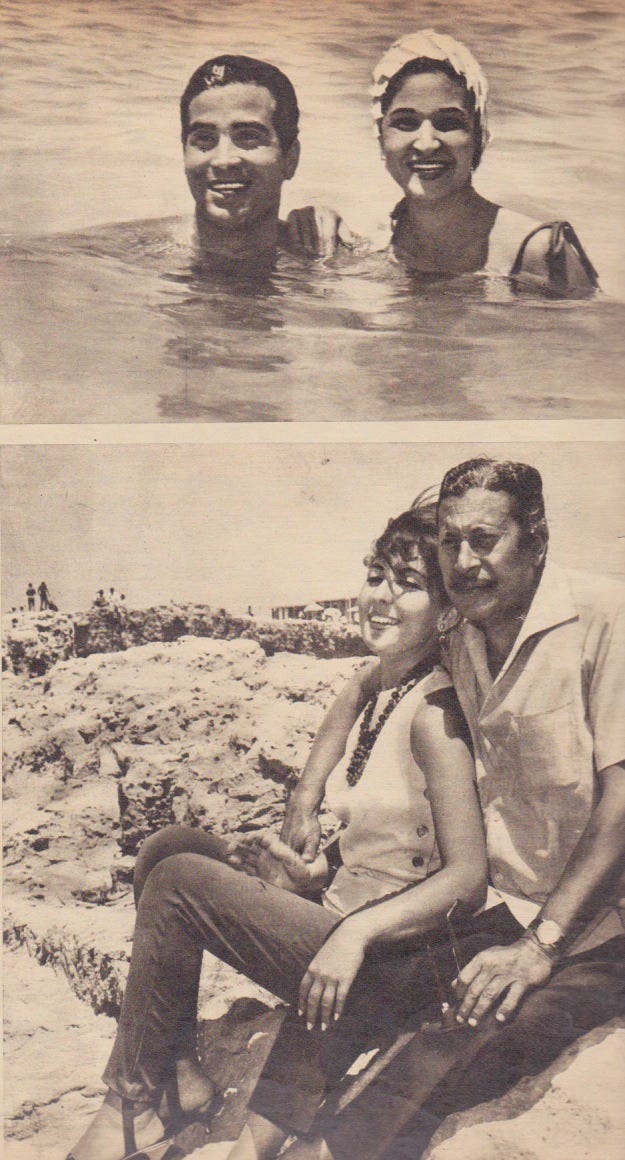

From the early to late 20th century, urban families increasingly Westernised. Studio portraits, street photography, magazines, adverts and my interviews with Egyptians all suggest liberalisation.

Studio portraits

Given Islamic proscriptions on image-making, strict Muslims may have been cautious about photography. Studio portraits are likely selective: non-Muslim, liberal, or secular. The pictures below were bought by Yasser Alwan at an Egyptian flea market. No details are provided: we don’t know their religion. Back in 1927, 9% of Egyptians were Christian. But these images are consistent with wider narratives of liberalisation.

This young woman had her photo taken at a photo booth.

Egyptians increasingly adopted Western dress

Baring their legs, this small group of women watch a soccer match between the Medical and Artillery Units of the Egyptian Army, which was attended by the King. Hemlines have risen, but ideals of segregation persist. Their section is clearly marked, “LADIES”.

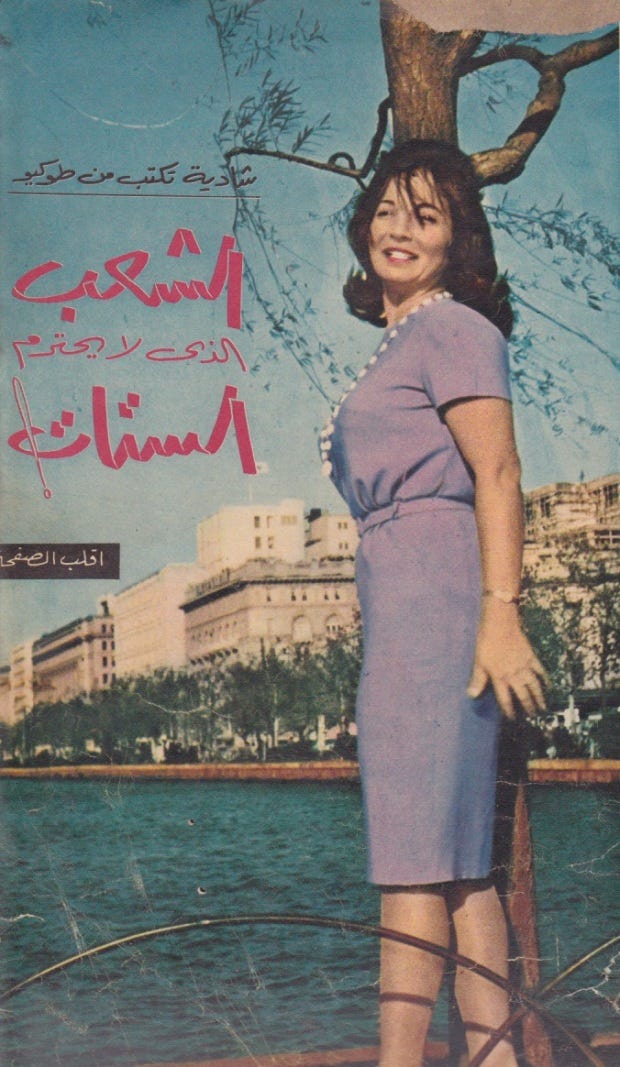

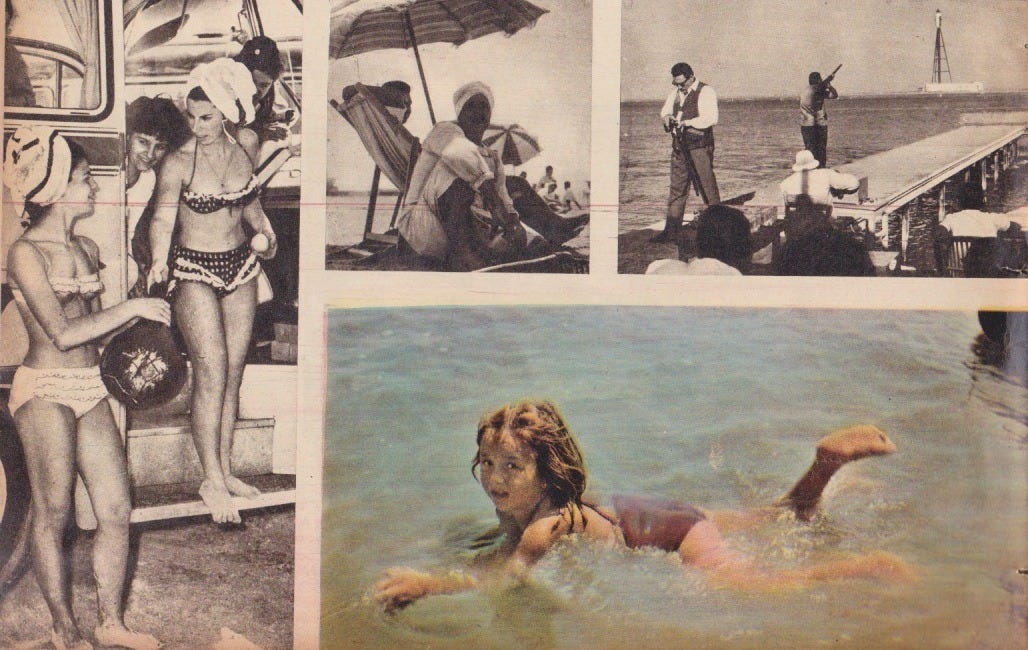

Magazines increasingly celebrated cultural liberalisation

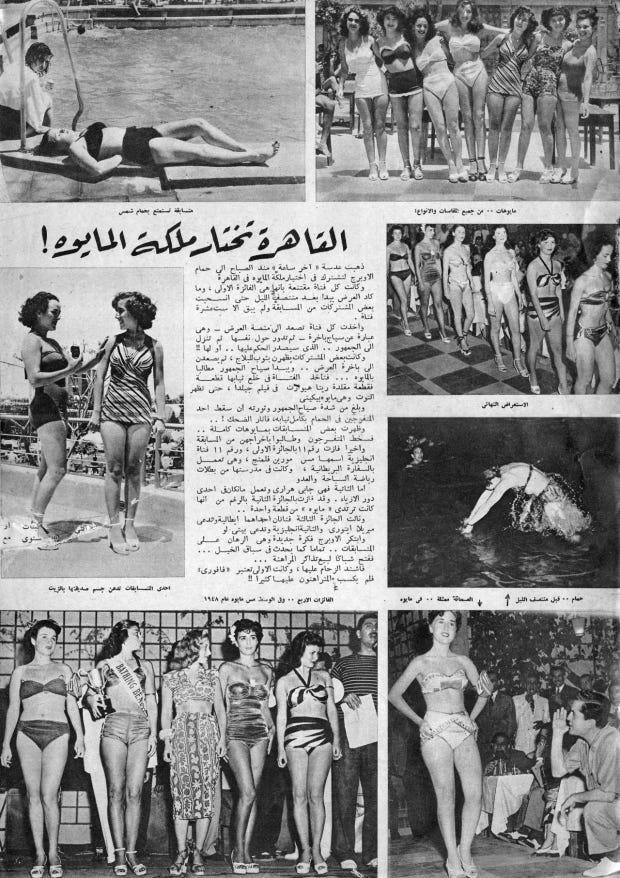

In 1949, Cairo hosted a swimsuit competition.

Beauty queen competitions in different Egyptian cities - 1956

“Ramadan in the summertime”

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have a new paper on why some cultures change, while others persist. They argue that Islam is relatively ‘hardwired’

“Unlike in the English or Chinese case, Islam leaves no room for legislation, for the law has already been created by God..

Although the tightly structured political system of Islam provided early benefits, it also constricted some cultural adaptations in response to fundamental international and technological changes in later centuries..

The entangled nature of Islamic culture may have also prevented cultural configurations that would allow political reform toward non-autocratic political institutions. Legislation remained God’s monopoly, reducing the role of legislative bodies”.

But these images of liberalising Egypt, indicate that some quarters did undergo rapid cultural change.

The text below reads, “Oh god, I am fasting”. She - with breasts bursting out of a bikini - is large, centre-stage, confident, defiant, and powerful, visibly mocking the cowering imam. Liberalism has won. In 2024, this image might be considered ‘rude’.

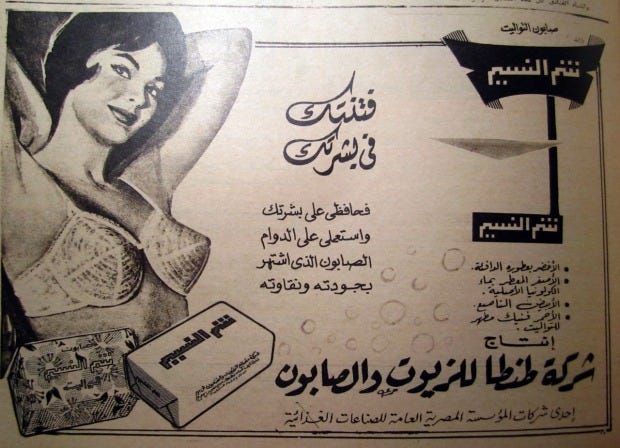

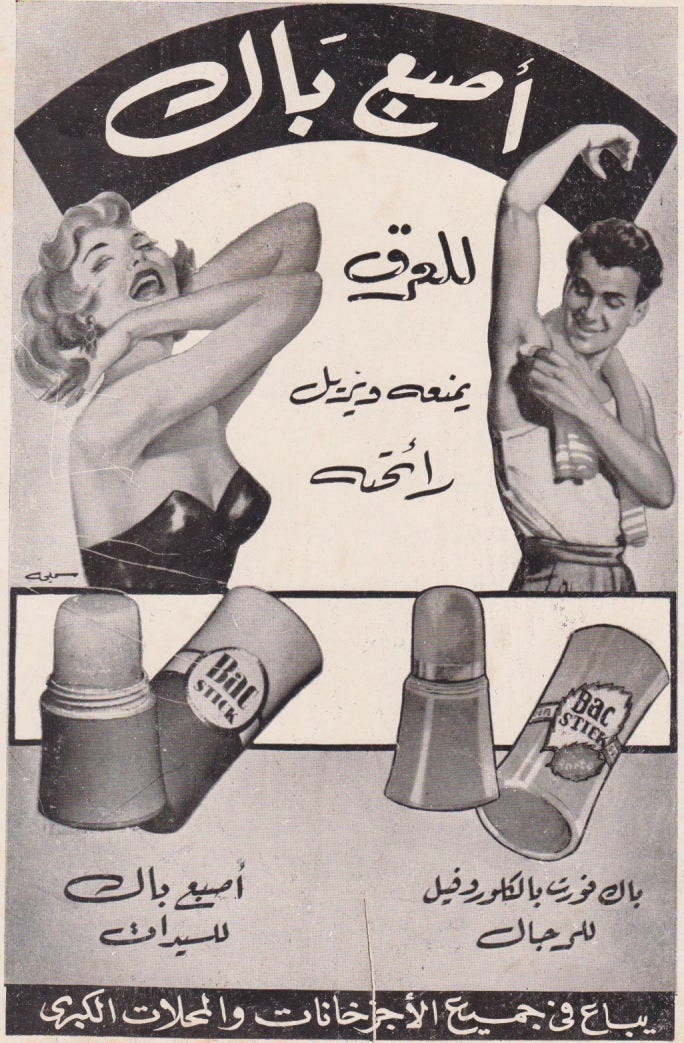

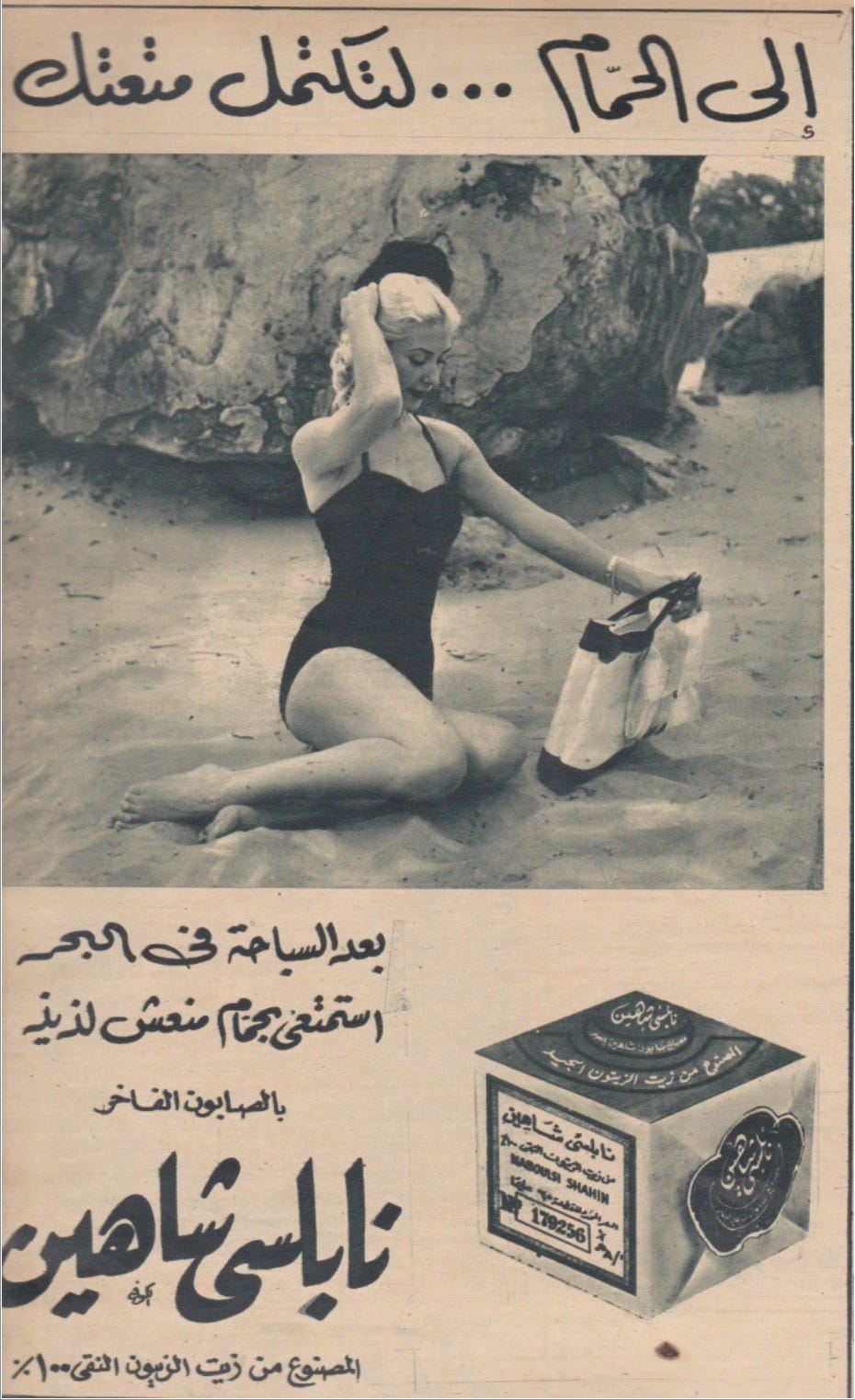

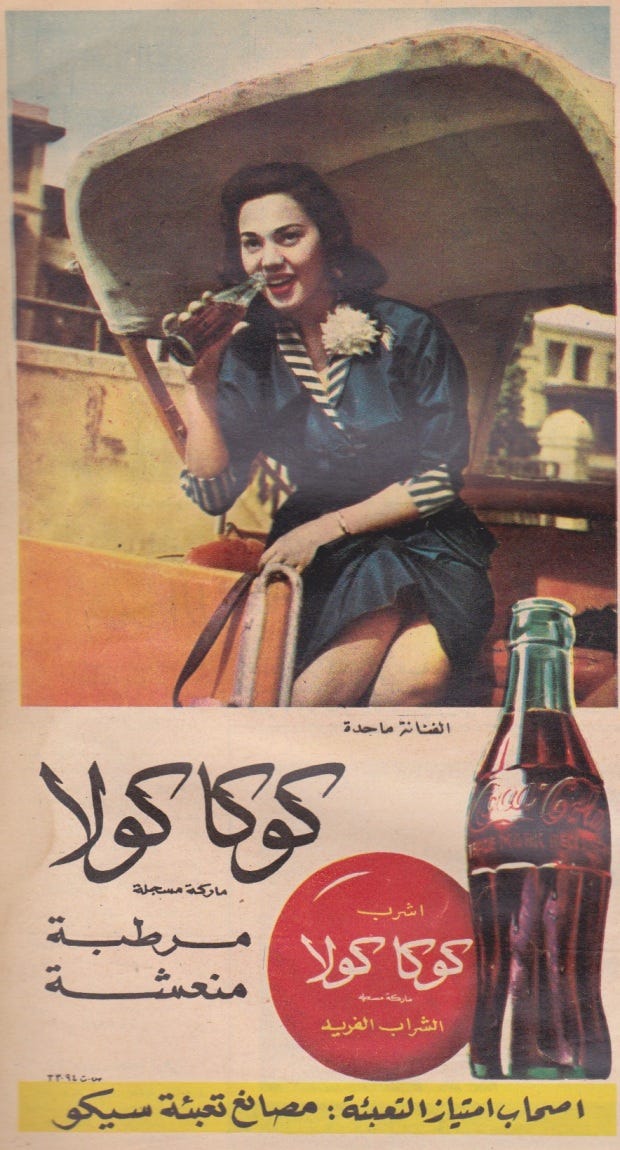

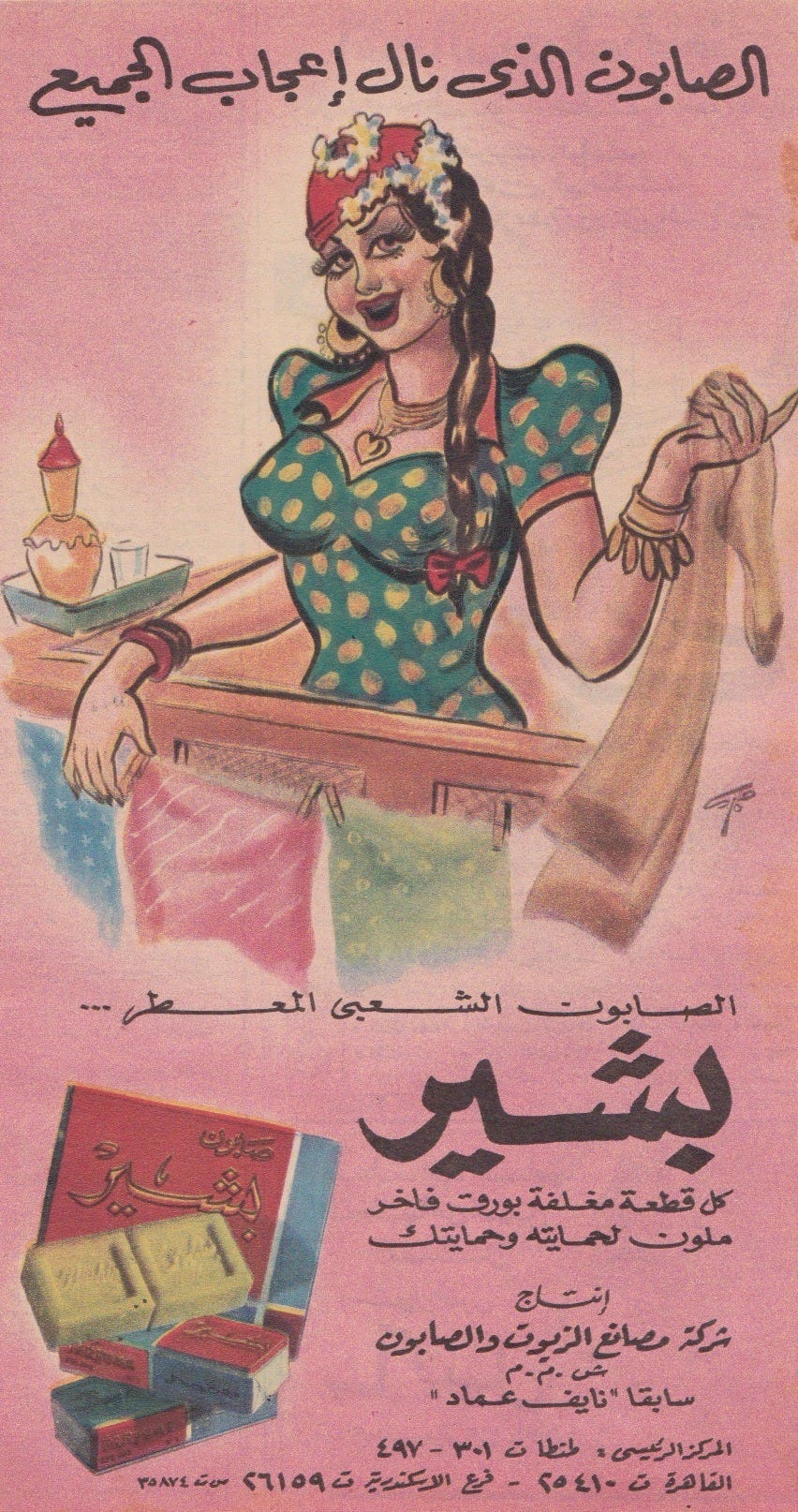

Adverts for everyday consumer goods show uncovered women

Adverts for low-cost consumer goods provide an excellent indicator of what the urban masses regard as socially acceptable. Sex sells, but companies may be cautious so as to avoid religious backlash. In the 1950s and 60s, Egyptian companies were marketing everyday items like soap, toothpaste, cigarettes, post mail, fabric care, soft drinks, radios and deodorant by using semi-naked models. They were trying to appeal to a large audience, while being immodest. Egyptian towns and cities were liberalising.

The first image is for hair removal cream, translated below. 1951.

These adverts are a greater signal of cultural liberalisation than photos. The latter may just capture the liberal elites who chose to have their photos taken. But these adverts are what companies thought would appeal to the masses, without fear from powerful and organised imams.

After the 1970s, by contrast, Egyptian politicians increasingly cloaked themselves in Islam in order to gain legitimacy. In the 1950s and ‘60s, that was unnecessary.

This 1964 advert is for fabric care, translated with Google. The woman on the top left is in a bikini.

This 1959 Egyptian advert for pain-killer features a green-eyed blonde. This aesthetic signals aspirational Westernisation. [I am not saying what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’]

This Philips radio is clearly marketed at rural farmers - marketed with a pretty young woman with visibly pert breasts and lip-stick.

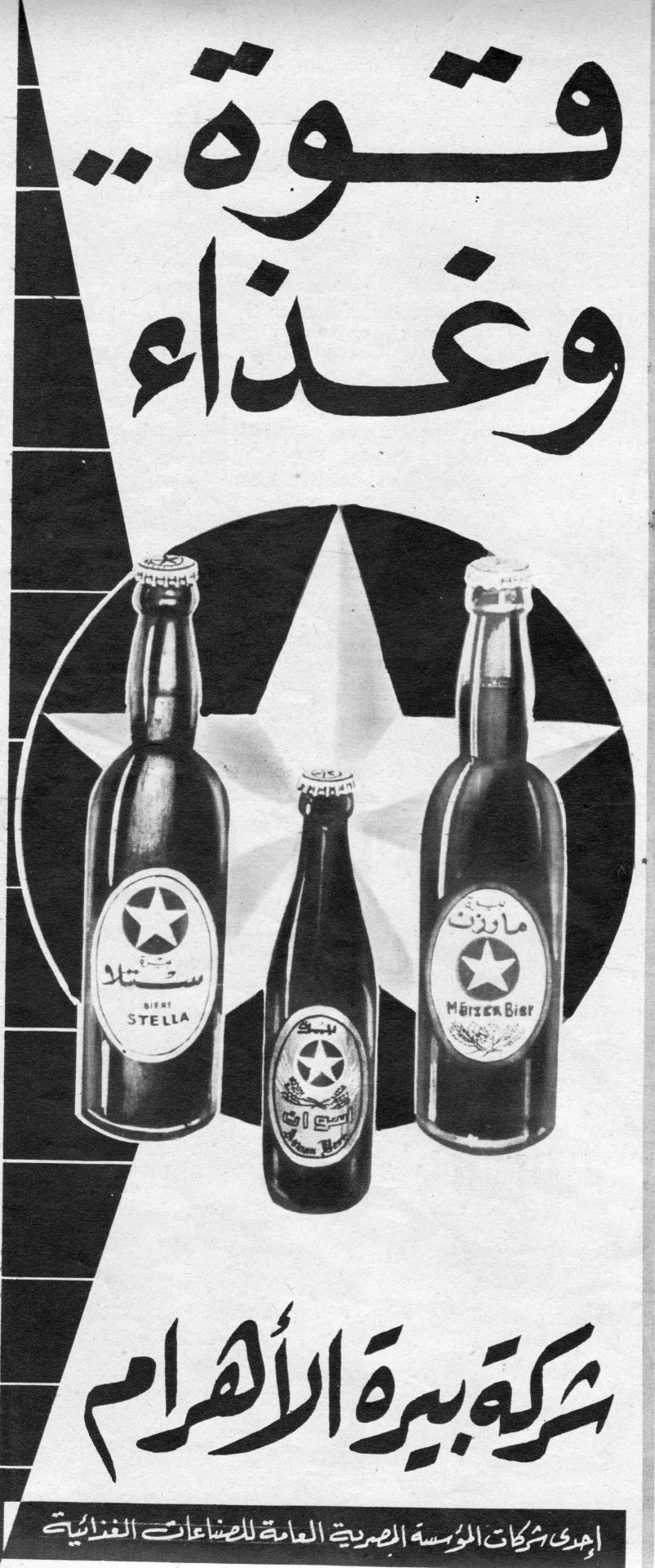

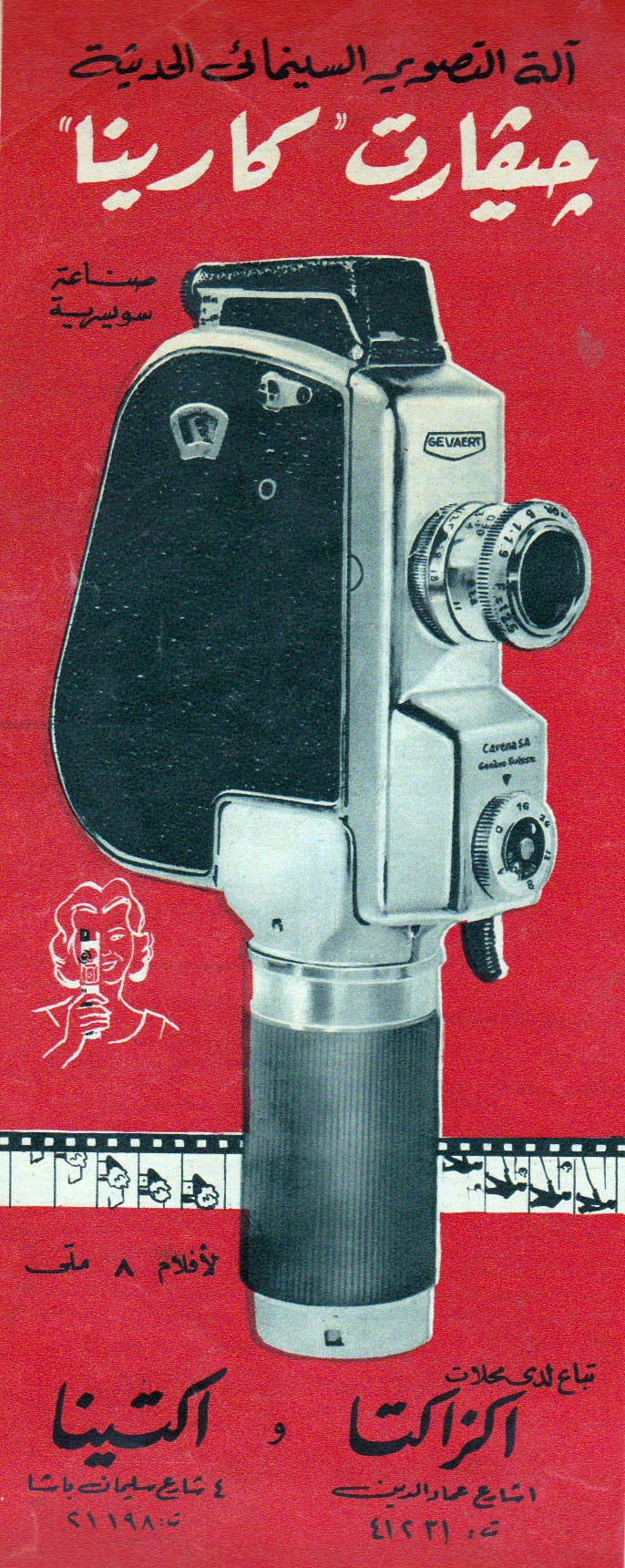

Adverts feature goods that were ‘haram’

Egyptian companies also advertised beer and video cameras, which are not permitted under strict Islam.

An unveiled, uncovered woman holding an ‘image-maker’ (video camera) - with minarettes in the background. 1951.

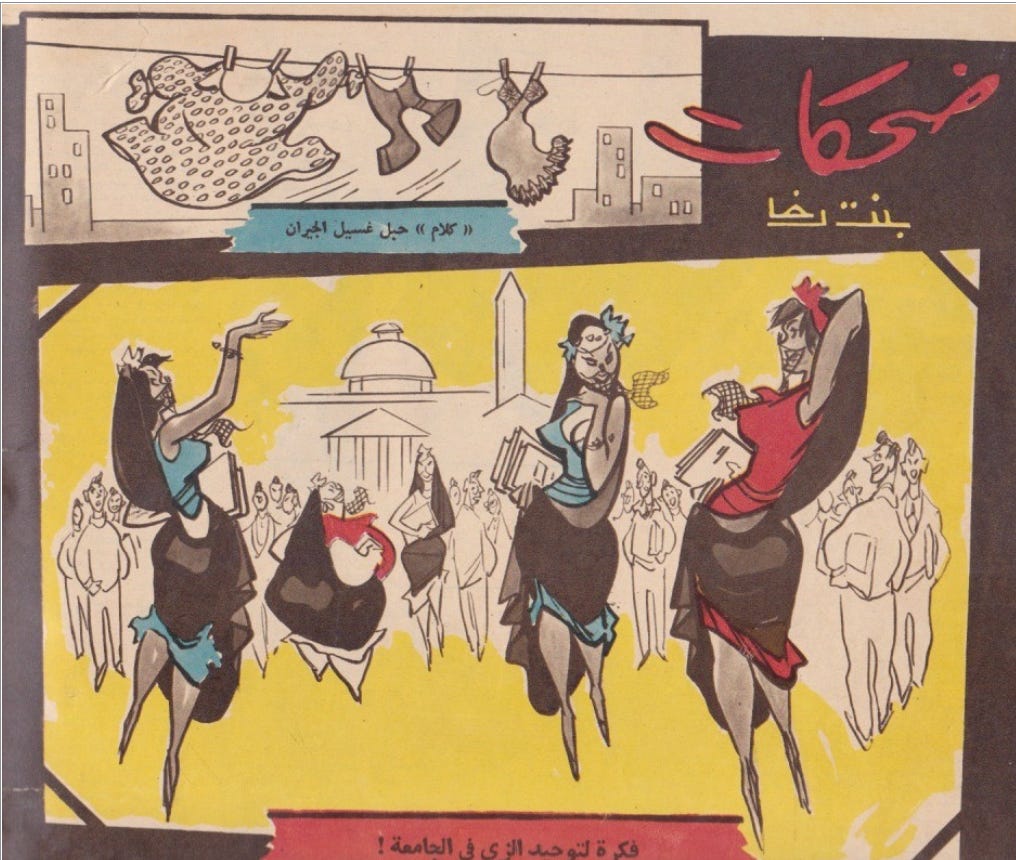

Blasphemous adverts?

This Egyptian advert might be deemed blasphemous. She is sexualising the traditional Islamic face veil. Advertisers do not appear cowed by fears of religious backlash.

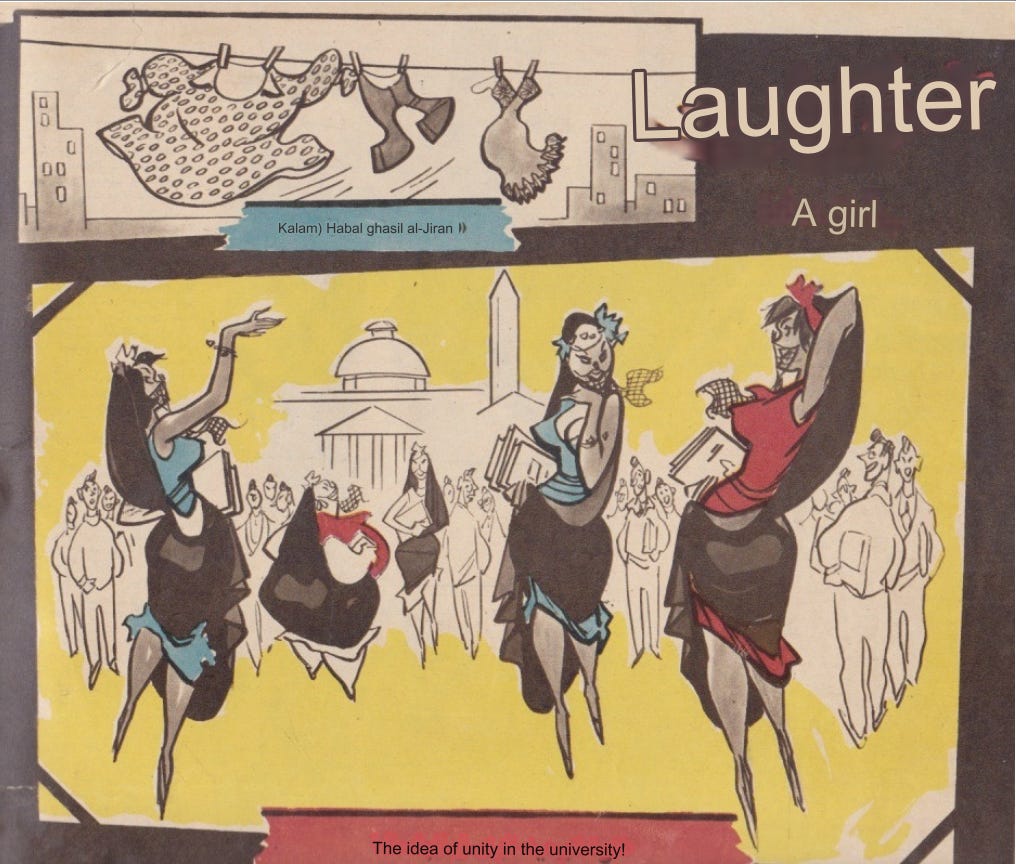

This is a comic response to a call for uniforms in universities. The women strut in their negligee, satirising face veils, with the mosque in the background. They could be interpreted as taunting Islam. 1961

Translated below.

Yet more adverts show unveiled women happily sitting alongside men in buses.

Advertisers also targeted richer clientele - with flights and scooters. These feature independent women, happy young couples and bare legs.

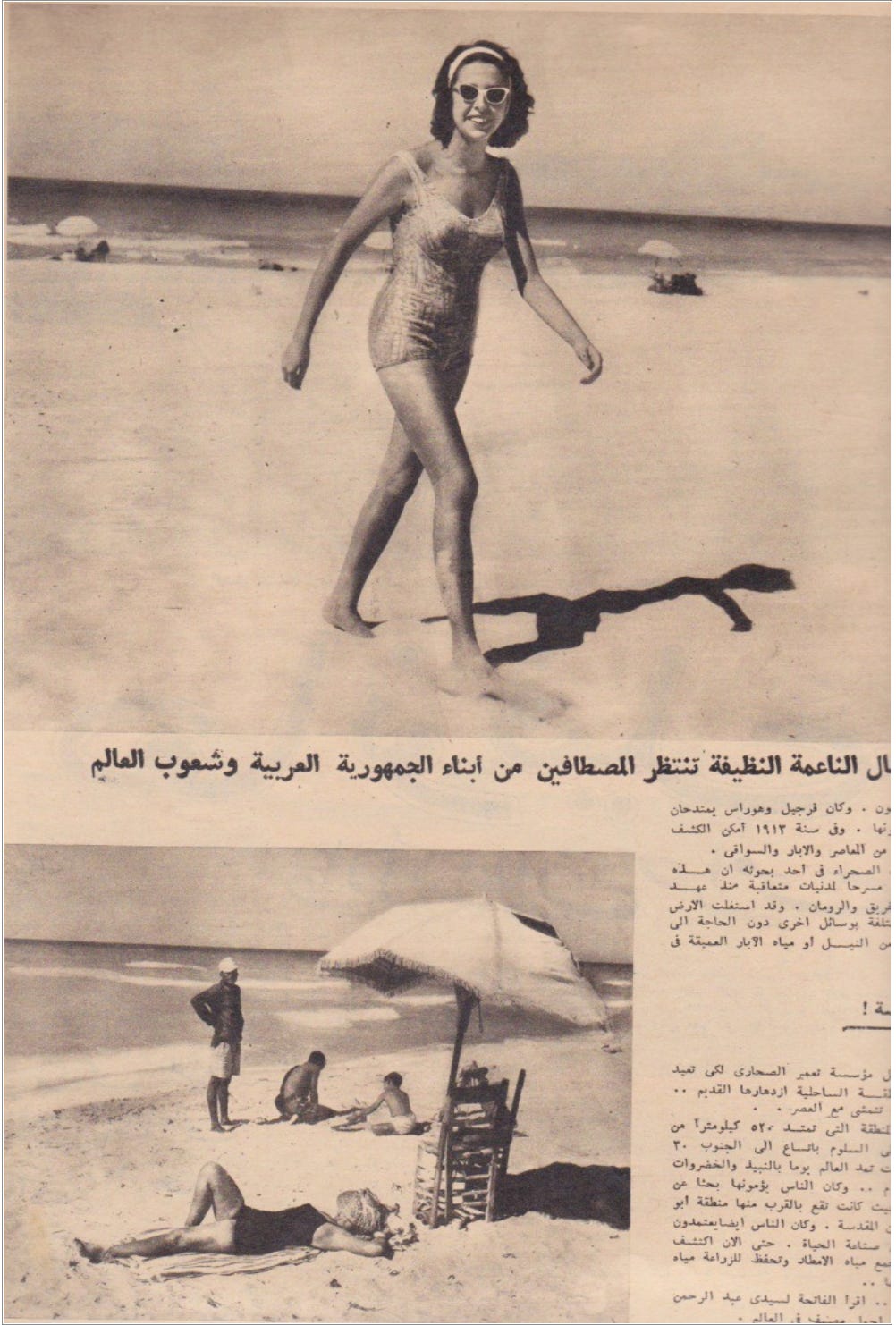

Seaside resort adverts, targeted at Egyptians, show semi-naked women

Seaside resort advert, featuring models in bikinis, translated with Google. 1962

Another advert for a seaside resort - targeting Egyptians.

This advert for Heliopolis Club entices Egyptians to escape the summer heat (with bikinis).

Street photography indicates cultural liberalisation

In 1957, men and women protested for Egyptian sovereignty over the Suez canal.

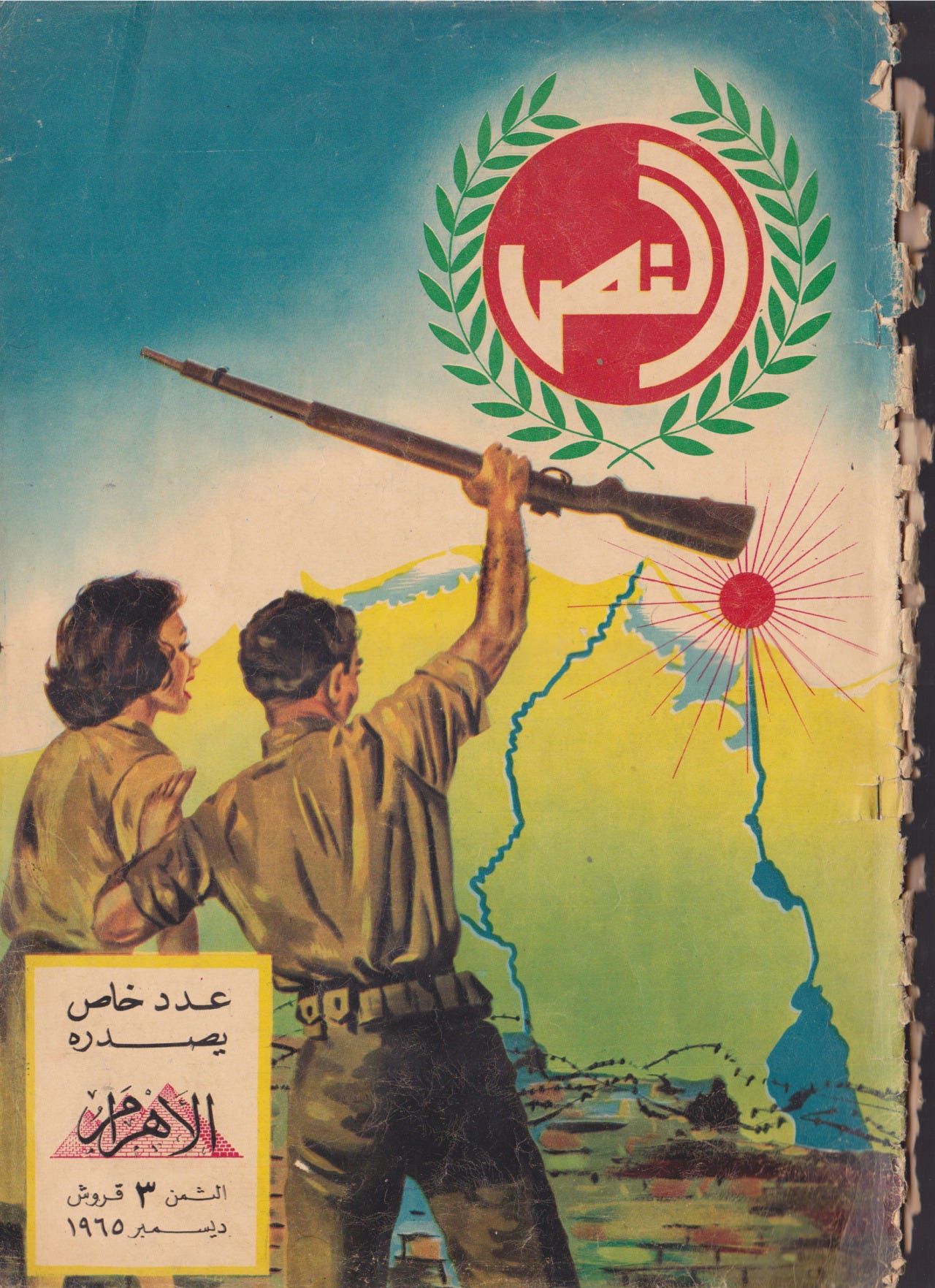

Under Nasser, a whole generation enjoyed massive economic uplift. This was an era of land reform, rights, education, secure jobs. Egyptians were optimistic; many embraced Westernisation as the path to progress. Middle class women in cities can be seen in short skirts and heels.

1964, Tahrir Square

This celebrates an Arab woman winning a swimming competition (translated with Google). 1962.

Abdel Hadi el-Gazzar was imprisoned for this (1951) painting, entitled “The Popular Chorus”. Lambasting the ruling elite, he shows a row of barefoot women, with empty bowls. Only two are veiled.

In 1958, President Nasser laughed at the Muslim Brotherhood’s suggestion that all Egyptian women should wear the hijab. His audience was highly amused.

President Nasser introduced a number of secularising reforms:

In 1955, Sharia courts were abolished.

In 1956, Al-Azhar lost authority over family law.

In 1961, secular subjects and women’s faculty were introduced to Al-Azhar.

President Nasser further recognised women’s right to register in electoral lists and run for parliament. The 1962 National Charter decreed:

“Women should have equal rights with men, and whatever shackles impeding her freedom must be broken off so that she can deeply and positively engage in social life…

Likewise, these values must reflect a free national culture and unleash the emotional effect of beauty in the life of a free person”.

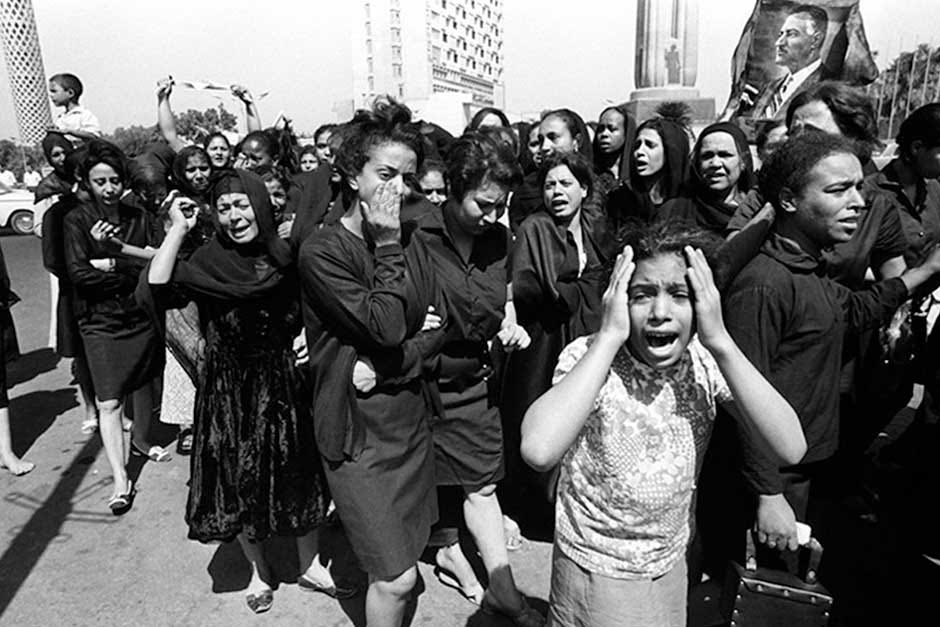

A crowd of Egyptian women rallied in support.

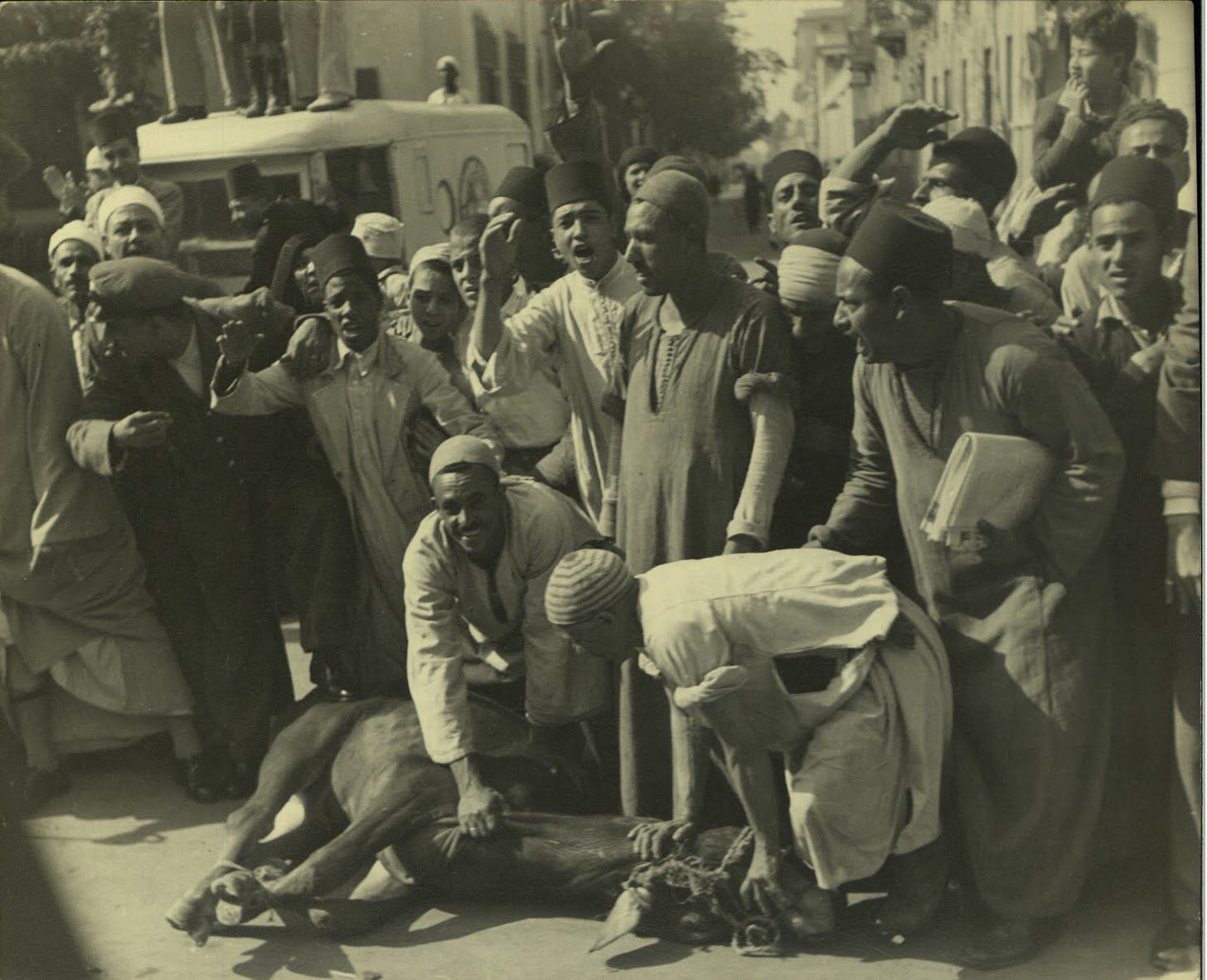

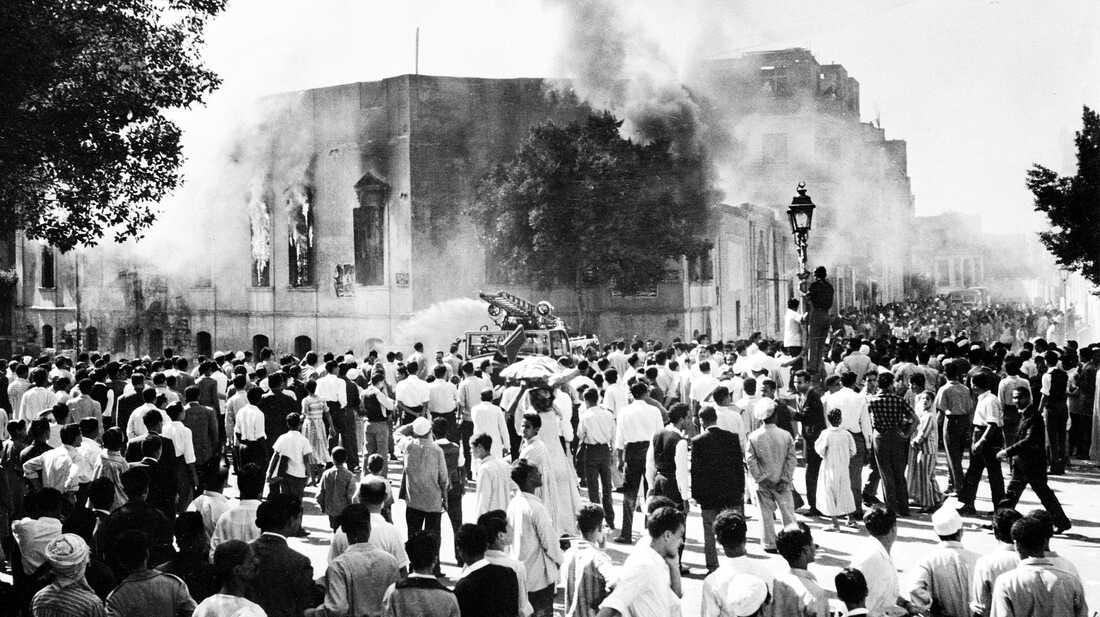

After the Muslim Brotherhood’s building was set on fire, photography shows a street scene that is entirely male.

This young woman - photographed by Van Leo in Cairo in the 1960s - wears a shoulderless dress, featuring scenes from Ancient Egypt. Religiosity is not salient.

This young woman worked at a state-owned factory manufacturing televisions. Her hair is tied in a Western-style ‘beehive’. 1963

In 1963, a young woman and her mother came to Van Leos’ photo studio in Cairo for a portrait photo. She’s wearing a ‘beehive’ - which was then popular in the West.

President Nasser died in 1970. 5 million people attended his funeral. Photos of the crowd show women in knee length skirts.

This 1973 photo by Van Leo captures an army officer and his bride in Cairo. Dressed in a white wedding dress and uncovered, they sport Western fashion.

Van Leo took this studio portrait of a couple on their wedding day. 1970s

This groom appears by his bride, in a shoulderless dress. 1980s. There is no sense of concern for protective sexual jealousy. They specifically came to Van Leo’s studio for this photo.

1980s Islamic Revival

Egyptians who came of age in the 1950s and ‘60s experienced national independence, social mobility and new economic opportunities. By the 1980s, economic progress was grinding down. Egypt’s purchasing power was plummeting. Middle class families could no longer afford basic goods, nor could the state provide.

As observed by Galal Amin,

“When the economy started to slacken in the early 1980s, accompanied by the fall in oil prices and the resulting decline in work opportunities in the Gulf, many of the aspirations built up in the 1970s were suddenly seen to be unrealistic and intense feelings of frustration followed”.

‘Western modernisation’ became discredited by economic stagnation and defeat by Israel. In Egypt, clerics equated modernity with a rejection of Islam and declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Islamic preachers called on men to restore order and piety (i.e., female seclusion). Frustrated graduates, struggling to find white collar work, found solace in religion, whilst many ordinary people turned to the Muslim Brotherhood for social services and righteous purpose.

As economic development stalled, political parties increasingly cloaked themselves in Islam to gain legitimacy. In 1973, the sale of alcohol to Egyptians was banned during Ramadan.

The Iranian Revolution inspired hope in the possibility of political Islam. Quranic reading groups, publishing houses, cassette tapes, missionaries, and mosques proliferated across the Middle East and North Africa.

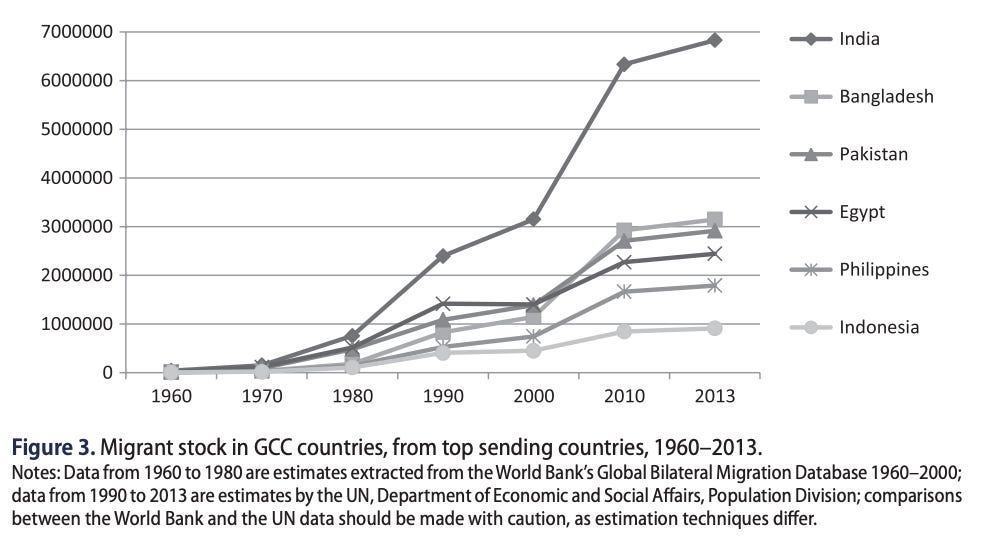

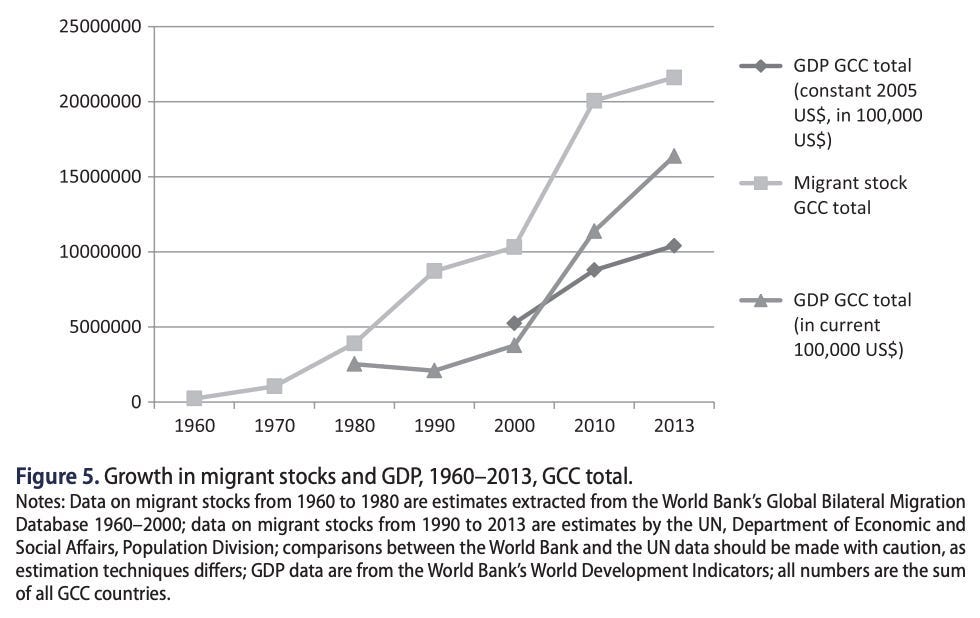

Western demand for oil has also made Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries extremely rich. Wealth funds mosques and madrasas that championed strict Salafism. Millions of migrants - principally from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Egypt, Philippines and Indonesia - have flocked to work in the Gulf, and see a land ‘blessed by Allah’.

Low-wage migration to the Gulf is directly correlated with oil wealth.

Migrants who travel to the Gulf for work often adopt Arabic culture, patriarchal ideologies, and heightened Salafism. This is reiterated by studies in Jordan, Kerala, Bangladesh, Sudan and Egypt. Migrants tell me precisely the same.

As Egyptians increasingly embraced religion, veiling became normative. Omnia Essawy writes,

“Although hijab is a religious choice, over the years, it has turned into an obligation. And it became unacceptable for women to walk around Egypt’s streets without hijab, hence the birth of the ‘righteous harassing phenomenon’ that flooded the streets”.

21st Century Egypt

Egypt is one of the most patriarchal countries in the world. Only 16% of women are in the labour force. Patriarchal authority is now widely accepted:

90% of men say that ‘a woman should tolerate violence to keep the family together’. 70% of women concur.

53% of Egyptian men think a woman may deserve to be beaten.

59% think men should have the final word on decisions in the home.

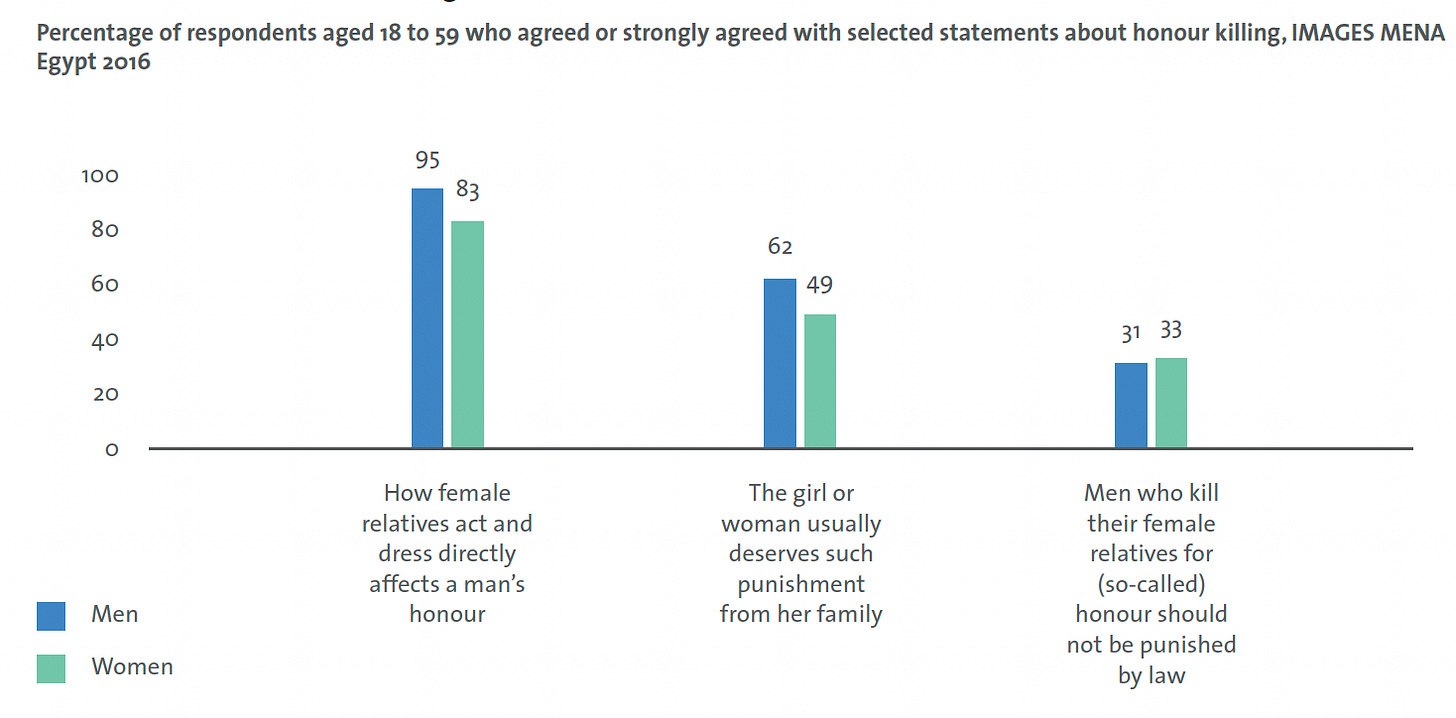

95% of men say that their honour is affected by their female relatives’ clothing and behaviour.

62% say a woman usually deserves such punishment from her family.

A THIRD say that honour-killings should go unpunished.

Whether rich or poor, rural or urban, young or old, there is very little difference in men’s gender beliefs. Patriarchy is extremely entrenched.

Egyptian husbands overwhelmingly say they control their wives’ movements, decide what they wear, and expect sex on demand.

Sexual harassment is widespread, and women are blamed. In Cairo, men lecher at women with impunity. They make sexually explicit remarks, grab, grope, and stalk strangers in the streets. Young women feel anxious, ashamed, and petrified about what onlookers might say, because victims are typically blamed for the actions of men. The presumption that women must have invited sexual aggression through indecent behaviour fuels the vicious cycle in which male relatives fear the loss of honor, and impose restrictions.

40% of Egyptian women report crying spells, or nausea, loneliness, fear, depression and low appetite - in the past week.

Repression of Feminist Activism

Authoritarian President Al-Sisi has repressed feminist activism. Feminist NGOs have been under travel-bans; their assets have been frozen. Courts continue to punish women for impropriety, legitimising victim-blaming.

Salma El Hosseiny writes that women have been sentenced to imprisonment for Tiktoks:

In 2020, at least nine women [were] arrested and charged with ‘violating Egyptian family values’. In July 2020, at least three women were sentenced to 2 to 3 years imprisonment and fined 300,000 EGP (roughly $19,000) for their social media content (singing and dancing to pop songs on TikTok).

The Prosecution's statement announcing the arrest of women social media influencers laid out the charges, which included ‘sexually arousing men’ by ‘singing and dancing in a way that attracts attention’ which has threatened ‘national and social security’, ‘corrupted our society and values’.

Big Data and Cultural Evolution

By analysing over 5000 years of statues, figurines, paintings, tapestries, literature, philosophy, vintage photography, advertisements and contemporary surveys, we see that Egyptian culture has undergone three remarkable transitions.

‘Tradition’ is not set in stone, nor can it be inferred from the 1800s Ethnographic Atlas. Instead, we need to trace and analyse every single step of the causal chain.

After Arab conquests entrenched religious authoritarianism and propagated Islamic ethicists like Ghazali, male honour became contingent on female seclusion. This persisted for centuries, since no man wanted be the first to relax restrictions and risk ostracism.

However, over the 20th century, Egyptians saw massive cultural liberalisation. Companions marketed low-cost consumer goods to the urban masses by showing pictures of women in bikinis. Street photography likewise shows rising hemlines.

Could this have continued?

Counter-factuals are difficult. But let us suppose Egypt had better economic management and that Saudi Arabia did not get lucky with oil wealth. While Mecca would always be a deeply spiritual place for pilgrims, its appeal may have dulled if it was dirt poor.

In some ways, Egypt has returned to precisely the same collective action it faced when Huda Sha’arawi publicly unveiled one hundred years ago. Men’s honour depends on female seclusion, and the overwhelming majority conform to maintain social respect. Yet again, patriarchal ideologies appear widely accepted.

Grateful to have had the opportunity to come across this today. I was just discussing with my fiancé how we, at least Americans, tend to have this view that progress is linear and always moving forward. But in reality, a closer look at history shows us that this is not the case, and thus we should not remain so silent and passive in the face of eroding rights, regulations, policies, and norms that we are experiencing.

Every time I read about culture and history, I am reminded by how restrictive, limited, and at times wrong my k-12 history education was. If our general education had more lessons like this, I wonder how different our society would be. Would we be more civically engaged? How would people respond to attempts to have more religious influence/involvement in government? Would we be able to recognize and stop the rise strong-man/authoritarian types? Would we respond any differently to marketing, advertisements, or propaganda?

There is so much knowledge and potential to have and maintain better societies, but we continue to struggle with many of the same issues that have plagued those before us.

It would kind of funny if Tesla and BYD do more for the rights of Muslim women than any of the pro feminist NGOs of the last twenty years.

On a side note wasn't there also a conservative backlash in relatively more affluent Muslim countries like Malaysia in the 1980s.