"Politicising Islam in Central Asia" by Kathleen Collins (Review)

Why is secularism sometimes unpopular? What drives demand for shariah law?

Kathleen Collins offers a brilliant explanation: when religion is violently repressed, people become riled. Sustained persecution is silencing, but as associational space expands, religious entrepreneurs mobilise the masses to defend their faith.

“Politicising Islam in Central Asia” presents a rigorous comparative analysis of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan over the past century, drawing on a wealth of evidence from archives, 154 oral histories with religious leaders, and 79 focus groups.

It’s superbly fascinating.

But is she right? What about other factors - like economics, corruption and prestige bias towards Saudi Arabia?

Repression fosters radicalisation and resistance

Many quantitative studies suggest that when people’s deeply-held beliefs are attacked, they cling to them even more tightly and organise strong resistance:

Secular schooling in Indonesia spurred demand for madrasas and religiosity;

Heavy bombings in Vietnams galvanised the communist insurgency and anti-US attitudes;

America’s Equal Rights Amendment triggered cultural backlash;

Rights for marginalised groups weaken support for democracy;

Existential threats (like terrorism, earthquakes and pathogens) cultivate demand for cultural tightness.

Causal inference studies typically focus on the exogenous threat: bombings, secular schooling, the ERA. But this is only half the story: it omits how cultural entrepreneurs actually mobilise the masses. What about social networks and ideological persuasion?

Kathleen Collins suggests that there are 3 pre-requisites for political Islam:

Religious repression

Sufficient associational space

Islamist ideology

Persecution spawns anger, but most people are petrified into silence. When crackdowns lessen, religious entrepreneurs seize new opportunities. They tap into widespread concerns, leverage sacred authority, and organise social networks.

That’s the over-arching schema. Now, let’s see the empirical analysis…

Islamic institutions were consolidated in urban centres, not the Steppe

Arab armies captured Bukhara and Samarqand in the early 700s. Tansoxiana became a great centre of Islamic science, philosophy, and well as trade. In towns and villages, Islam was institutionalised through maktabs, madrasas, mosques and courts. Muftis (legal scholars), mullahs (religious leaders), imams (mosque prayer leaders) qazis (respected teachers), and otinchas (female religious teachers for women) kept order.

Turkic nomads, by contrast, only adopted Islamism superficially. Sharia law was scarcely observed on the Steppe, nor were there many mosques or madrasas.

Local reformists emerged in the early 1900s. Jadids (wealthy merchants and educated elites) lambasted the ulama as ignorant and greedy. But in places with strong Islamic institutions (e.g. Fergana), they faced major resistance.

Fergana & Tajik towns: Bolshevik repression & Islamic resistance

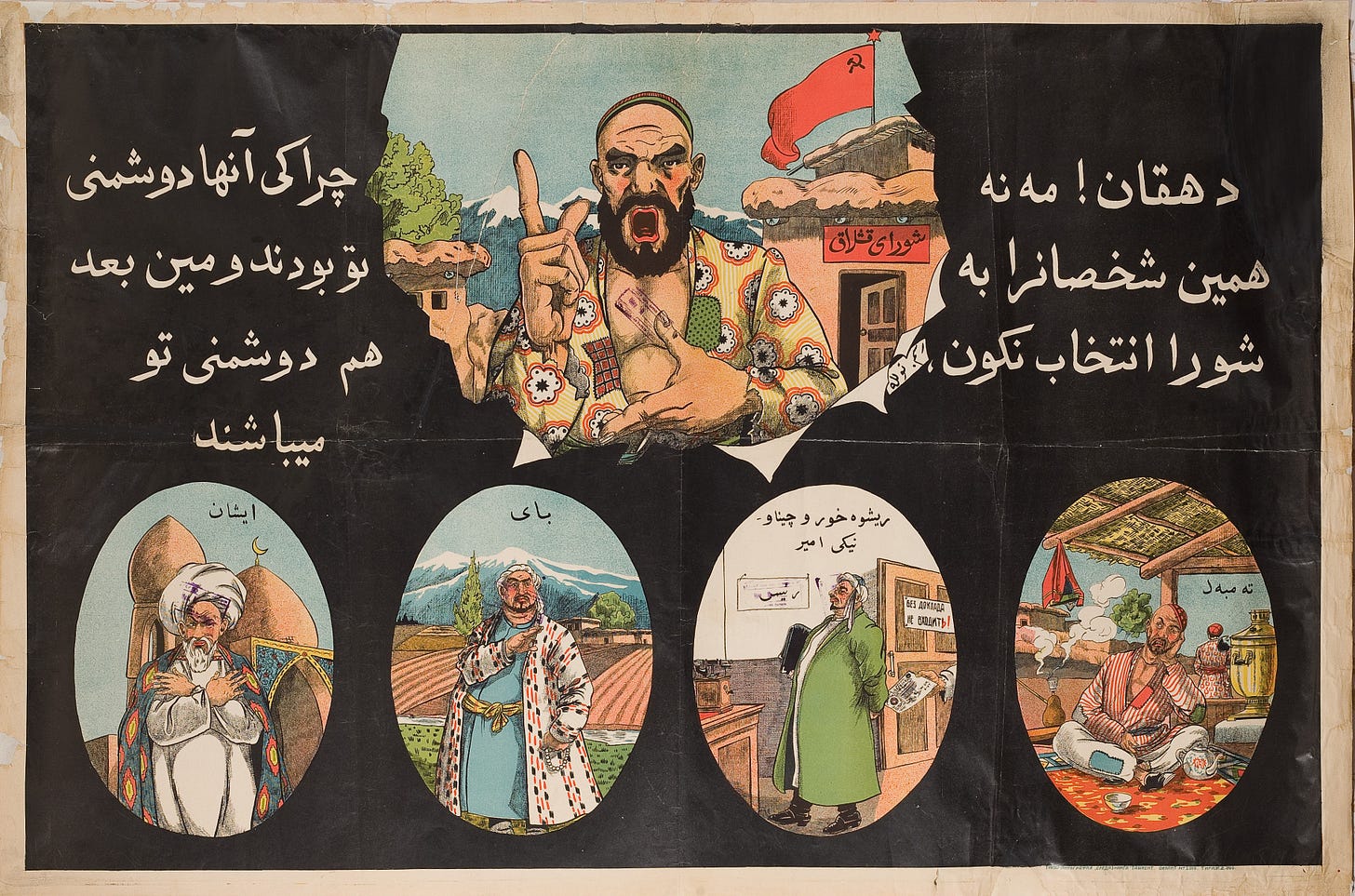

Bolsheviks assaulted Islam. Religious properties were seized, Islamic marriage rituals were banned, and the 1918 Soviet Constitution denied suffrage to clergy. Once the Red Army conquered the Bukharan Emirate, they destroyed shrines, banned Muslim funerals, instilled secular schooling, and spread anti-religious propaganda.

The Bolsheviks were not totally repressive, insists Collins. There were still spaces for Islamic mobilisation. Between 1921 and 1923, the Bolsheviks even made tactical concessions: permitting shariat courts; returning wafqs; and temporarily rescinding the ban on madrasas.

Feeling threatened but not petrified, Islamic activists stirred into action. In Tashkent 1917, the ulama organised and won the largest duma bloc. They declared,

“Everything from schools to questions of land and justice should be solved according to the shariat”; “women should not have rights equal to those of men, but everyone should have rights according to one’s station as adjudged by the shariat.”

The Bolsheviks amped up repression, dissolving this duma. Ulama then headed to the counter-revolutionary centre of Kokland, proclaiming “[We want] shariat courts, our system of land tenure.. women to remain veiled and subordinate,” unlike “Europeans.” The Red Army opened fire on demonstrators, slaughtering over 10,000.

Repression fuelled yet more Islamic militancy. In Fergana Valley and eastern Bukhara, religious and tribal leaders launched the ‘Basmachi’ insurgency, demanding a return to Islamic traditions. Soviet officials reported widespread survival of Islamic institutions and the closing of women’s clubs. Fergana and the Tajik republic were deemed fanatically Islamic.

Kathleen Collins argues that this iteration of repression, contention and violence exacerbated the politicisation of Islam.

Turkestan & the Steppe: less contention, more inclusion

Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Turkmen, and Karakalpak nomads were seen - by Soviets - as “superficially” Islamic. Thus, there was less religious repression - argues Collins.

Collins argues that differential treatment largely reflects Soviet “stereotyping”.

I’m not so sure.

Nomads continued to worship ancestors and practise shamanism. Sedentary and steppe cultural differences also show up in genetic data. Nomadic Kyrgz practised exogamy. In settled areas of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan (where there were strong Islamic institutions), families tend to marry their relatives. I suggest this reflects Arabisation.

Southern Uzbeks only adopted agriculture in the 16th century. What happened when they became farmers? Their Y-chromosome diversity reduced. Uzbeks embraced Islam and gradually adopted endogamy.

The genetic data indicates that it wasn’t just “Soviet stereotyping”. In villages and towns, there was stronger Islamisation and Arabisation.

As I see it, given the Steppe’s paucity of powerful ulama, mosques, madrasas, and veiling, Islam was not a politicised frame of resistance. Thus as Collins details, the Soviets were optimistic about integration, so did not destroy the popular Sufi shrine of Khoja Ahmad Yassaviy. Moscow prioritised collectivisation and sedentarisation. Clan elders were removed, to pave the way for true communism.

Red Terror

From 1926, Stalin ordered the elimination of Islam. Mosques, madrasas, maktabs, shariat courts, and mazars (shrines) were closed. In 1922 Fergana, there were 122 shariat courts. By 1922, there were only two.

Between 1927 and 1939, fourteen thousand imams and mullahs were killed or disappeared. Thousands more were sentenced to the Siberian Gulag. The Poliburo also imposed Cyrillic, to obstruct Islamic knowledge.

In the hujum campaign, the Soviets encouraged mass unveiling. Thousands of women women attacked and murdered by their own communities, who sought to prevent unveiling through terror.

But among the north Kyrgz, Kazakhs and Turkmen, the the hujum was met with little resistance. Nomads had never idealised female seclusion.

Continued Repression

From the 1940s, political persecution marginally diminished. Defeating Hitler required all hands on deck. The Politburo even made a concession: a state-controlled Islamic body. Later on, after Stalin’s death, Gulag prisoners were released.

In 1958, Khrushchev stepped up the violence. Sufi shaykhs, study circles, and shrine visitation were purged. Sufism was driven underground. Mountain Tajiks were forced to leave sacred shrines and work in the lowlands.

Brezhnev curbed arrests, but maintained surveillance, fines and harassment. Mosque registration was still refused.

Older imams told Collins that this fuelled grievances and religious zealotry.

Islam Survived

Muslim identity, practices and beliefs survived. “Faith was always there”; people “consciously deceived” the state - explained elderly Tajiks and Uzbeks. Circumcision, marital and funeral rites were still performed. Namaz, fasting, and shariat remained central to their identities.

In Fergana town and south/central Tjik, clerics taught illegally in private hujra networks. Men met in choyxonas (tea houses) and other spaces that escaped surveillance.

An Uzbek imam told Collins:

“During the Soviet era there were many who helped save [Islam]… There were secret hujras and in these places they [ulama] taught people. There was a small courtyard in the basement where people gathered and secretly performed namaz. There was a time when twenty young guys were arrested and put in prison for this, around 1980. Such hujras were in the Ferghana Valley and far-off villages. Teachers told children in the hujras not to tell anyone about it, even their parents. . . . Everything was secret”.

“Of course, we also had nikoh! Our wedding was legal... Then at home we said nikoh. . . . My mother would not have allowed it! . . . Without nikoh, marriage is haram [forbidden]!” - explained a woman, married in 1960.

In Tashkent, Soviet foot soldiers exaggerated success to please senior officials.

On the Steppe, by contrast, Islam was never institutionalised, nor central to Kyrgz identity. Elderly Kyrgz respondents instead defined national culture in terms of ‘‘hospitality”, “lineage” and “respect for elders”.

Soviet atheism was less contentious on the Steppe, argues Collins. And since the Party did not perceive Islam as a major threat, it became more tolerant (from the 1970s). Elderly participants recalled,

“The Party did not bother us . . . but for seventy years we had moved far away from Islam” (deputy mufti).

“We had freedom [to pray], and there were no arrests of Islamic spiritual leaders then… so the mosques were not an ‘opposition’” (imam in southern Kyrgyzstan).

“One could read the Qur’an, and the state wasn’t in the mood to try to influence or pressure such people” (imam).

Given religious tolerance, Islam never became a major frame of political opposition. Imam Mansur recalled that in the late Soviet years,

“Mullahs did not carry out any anti-state activities. Their opposition to the state ended with passing on religious knowledge to simple people… teaching them to say prayers, fear Allah, and study suras of the Qur’an and the rules of namaz. That was their work... It was not opposition to government policy.. Thanks to Allah there was no Islamic opposition. Who needs it?”

Meanwhile, some Kyrgz even embraced atheist education, plays, music and films. Women seized new opportunities.

Greater freedoms permit Islamic Revival

In the early 1990s, Kyrgyzstan began to liberalise. Namaz, the hajj, mosque construction and Islamic rituals were all allowed. Religiosity surged. More Kyrgyz identified as Muslims, fasted, attended Mosques, made the hajj, and studied the Qur’an. Madrasa enrolments increased by over 3,300 students every year. More mosques than schools have been constructed since 1991. Alcohol consumption and mixed sex intermingling in weddings declined.

Kyrgz were never that devout, so what explains this Islamic revival??

Collins mentions Arab influence, Cairo’s Al-Azhar University, Kuwaiti donors, and ideological persuasion. I suggest four further hypotheses: (1) economic stagnation may have increased religosity; (2) people may have sought a moralising supernatural force to dispense justice; (3) signalling commitment may have helped secured access to club goods (as in Brazil); (4) once religiosity became widespread, people may have performed piety to maintain social approval.

Whatever the underlying reasons, religion was revived. But this did not manifest in Political Islam. Multiple civic organisations pressed for more Islamic influence, education and laws, but no political leaders actually sought to overthrow the secular state. Collins concludes:

“Kyrgyzstan has shown us that a regime’s liberalization of religion can lead to widespread and long-lasting Islamic revival, but without the emergence of Islamism”.

Repression is radicalising

From 2005, the Government of Kyrgyzstan stepped up religious repression, especially targeting Uzbeks. The state became intolerant and brutal.

Repression was radicalising - argues Collins. People turned to Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami (HTI) - which sought to overthrow secular regimes and establish a caliphate.

Repression in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan caused similar radicalisation. Brutal crackdowns spawned stronger resistance - which led to more show trials, beatings, widespread arrests, torture, killings, and legal restrictions. In Uzbekistan today, schools and universities frequently evict women wearing the hijab.

Religious entrepreneurs have also played a role. Recording sermons on cassettes and more recently YouTube, they called on Muslims to emulate Saudi Arabia and Salafism. Many have gone viral, amassing hundreds of thousands of views.

Unsuccessful Secular Authoritarianism

Collins’s over-arching argument is brutal repression drives radicalisation. My only caveat is that her focus groups with ordinary Uzbeks, Tajiks and Kyrgz suggest an additional mechanism: rampant corruption and frustration with government failure.

Everyone interviewed reiterated their anger with both state violence and corruption. Many believed that Islamisation and sharia law could bring justice:

“There will be less corruption in a country where the laws are Islamic.”

“If laws were based on the shariat there would be no corruption.”

“Police and the courts have no conscience. They show no justice.. In an Islamic state there is justice.”

Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami (HTI) campaigned on precisely this. One leaflet blamed all problems on “the unsustainability and injustice of the existing system... far removed from the flawless Islamic system”. HTI repeatedly attacked repression, injustice and corruption.

Collins does not mention this, but if secular authoritarianism is seen as deeply corrupt and dysfunctional, then it’s plausible that one might place hopes in political alternatives, especially if those alternatives are praised as pious and pure.

Many of her participants specifically said they want to emulate Saudi Arabia’s success. This all points to prestige bias. The most puritanical Muslim country happens to be very wealthy. Beyond the material funding provided by Kuwaitis and Saudis, their pre-eminence begets admiration.

Acemoglu, Ajzenman, Aksoy, Fiszbein and Molina have a new paper called, “(Successful) Democracies Breed Their Own Support”. Worldwide, people are much more supportive of democracy if they live in a democracy that provides economic growth, peace, stability and public goods.

Central Asia reveals what happens when secular authoritarians are not only brutal, but fail to deliver.

Collins focuses on three countries where growth has been relatively low. Kazakhstan is just as repressive as its neighbours. But Kazakhs are half as likely as Kyrgz and Tajiks to say that religion is “very important”. Kazakhstan is just as authoritarian as its neighbours, but has supplied far fewer fighters to militant Islamist organisations in Syria and Iraq. I suspect this is because the Steppe was only superficially Islamic and oil wealth has enabled prosperity. Today, in cosmopolitan Almaty, Qpop bands have amassed great success by celebrating liberal dissent and defiance.

“Politicising Islam”, beyond Central Asia

In the absence of violent repression, Muslims do not necessarily seek Political Islam. 1990s Kyrgyzstan fits this model.

But when religion is attacked, it becomes politicised as a major bone of contention. As authoritarians finally alleviate restrictions, religious entrepreneurs then organise the masses to defend their faith.

Collins gives further examples of Chechnya and Afghanistan.

Stalin’s forced deportations of Chechens in the 1940s spawned resentment and national identity. In the 1990s, Islam was the major frame of opposition mobilisation against the Russian state. After Chechen leadership adopted shariat law, Putin relaunched war, bringing the Chechen death toll to 200,000. Remaining Chechen fighters joined ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

In Afghanistan, the mujahidin emerged in opposition to the anti-religious communist party, backed by the USSR. Tens of thousands joined forces to repel the Soviets.

The trend is compelling, it’s a fantastic book! But…

In the counter-factual absence of Soviet authoritarianism, would Uzbekistan really have become a more secular democracy?

Why didn’t post-Soviet Eastern Europe see the eruption of ‘Political Christianity’?

Even in threats are not physically violent, there can still be religious backlash - as occurred after the introduction of secular schools in Indonesia.

A wealth of evidence suggests that economic downturns, natural disasters, and conflict motivate demand for norm policing and strict theology.

Oil-rich Kazakhstan is just as authoritarian as its neighbours, but people are far less religious. So I wouldn’t underestimate the economics.

What do you think?

Without having read the book, I think the role of Saudi and Turkish resources in leading an Islamic revival cannot be underestimated. They funded the construction of mosques and schools, distributed religious literature, and supported philanthropic efforts.

https://voicesoncentralasia.org/mosque-diplomacy-in-central-asia-geopolitics-beginning-with-the-mihrab/

Meanwhile the Tablighi Jamat was also leading revival efforts:

https://carnegieendowment.org/2015/03/19/reviving-central-asia-s-religious-ties-with-indian-subcontinent-jamaat-al-tabligh-pub-59481

To the best of my knowledge, there was no comparable effort at leading a Christian religious revival in Eastern Europe. Very much the opposite -- as they drew closer to the EU, the cultural pressure was to become more liberal and secular.

Do you think islamism will die down as the GCC countries loss a lot of their wealth and power after the EV revolution?