Why Do Hindu Women Work Abroad but Less so in India?

Dear reader,

I wish to present a puzzle.

In Britain today, Hindu women's employment has soared to 58%, while their Muslim counterparts lag behind. (This holds controlling for individual characteristics, so does not reflect migrant selectivity). Yet in South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, female labour force participation remains stubbornly low across religious groups. In India itself, Muslim and Hindu women express similar gender ideologies. Understanding this paradox offers crucial insights into the drivers of patriarchy, and the pathways to gender equality!

Sanskritisation

To solve this conundrum, we need to grasp how Hindu communities came to adopt and enforce female seclusion. When Muslim rulers conquered India and established their administrations, they idealised female seclusion. Hindu elites began adopting purdah to gain patronage and social standing. But how did these practices spread beyond the courts, penetrating remote villages where peasants never glimpsed a nobleman? The answer may lie in India’s distinctive caste system.

As M.N. Srinivas famously detailed, the varna model of four ranked categories - Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra - evolved gradually during the Vedic period. By around 500 BCE, Brahmin writers had established a divine hierarchy placing themselves at the top.

This idealised four-fold system obscured a more complex reality of hundreds of jatis (endogamous groups) in each linguistic region. Membership was secured through marriage, with members preferentially doing business together, helping find jobs, providing emergency loans, and cooperating in countless daily interactions. Being outcasted meant losing access to these vital networks of mutual support and opportunity.

Higher castes maintained their status through elaborate rules of purity and pollution. This ritual hierarchy created a powerful drive for upward mobility. When lower castes acquired wealth, they sought to translate this into higher ritual status by adopting the customs of castes above them - what Srinivas terms ‘Sanskritisation’.

Entire jatis (endogamous groups) would collectively adopt upper-caste practices, including female seclusion. A peasant caste might withdraw women from agricultural labor and enforce strict purdah - even at significant economic cost. The local dominant caste served as their immediate model, having themselves adopted these practices from higher ranks. Individuals could not easily resist, as castes policed their own members. If a family allowed their women to work in the fields or move about unveiled, the caste council could declare them outcaste - severing their marriage networks and social ties.

Caste Prestige and Social Policing

The power of these social pressures became starkly evident in early 20th century India. In 1900, Kanpur witnessed a five-day riot after medical authorities removed a Bania widow diagnosed with plague - a violation of purdah. As Charu Gupta explains, this was a violation of purdah. To placate massive social unrest, the colonial government stepped back, making exemptions for ‘respectable’ women.

Women’s public visibility and wage earning stained an entire jati. The Agraharis were shunned when their women worked in shops, the Khatiks were stigmatised when their women sold produce on streets, and certain Gujar families were degraded when their women ventured out to trade.

“The sign of high caste women is that.. they do not even allow their women to enter a man’s ears”, proclaimed Balabodhini, Harishchandra’s journal for women in 1874. Jatis across the social spectrum responded by tightening restrictions on their women. Urban Chamars adopted strict purdah, Lucknow’s Khatiks confined their women to shops rather than streets, and Ahir men prevented their women from selling milk. Even when these restrictions severely hurt household incomes, jatis prioritised honour over economic gain.

Technological advances paradoxically strengthened these restrictions, by enabling ideological persuasion at far greater scale. Hindu publicists could reach smaller towns and villages. Caste associations published pamphlets shaming lower castes for women's ‘indecency’. Railways created fresh anxieties about women's mobility, with calls for strict purdah in public spaces.

Even though Hindu publicists repeatedly attributed purdah to Islamic rule, they simultaneously sought to preserve this source of prestige.

21st Century Sanskritisation

Strikingly, these patterns persist in the 21st century. Analysis of recent India Human Development Surveys shows that when families experience upward economic mobility, they significantly increase restrictions on women’s physical mobility and adopted purdah. The effects are especially strong among Dalits and Other Backward Classes, as well as poor or rural communities, and the least-educated.

The Hindu Diaspora

Yet when we look beyond India, a striking pattern emerges. In Britain, where casteist policing and purdah-prestige are far weaker, Hindu women have achieved remarkable workforce participation rates of 58%.

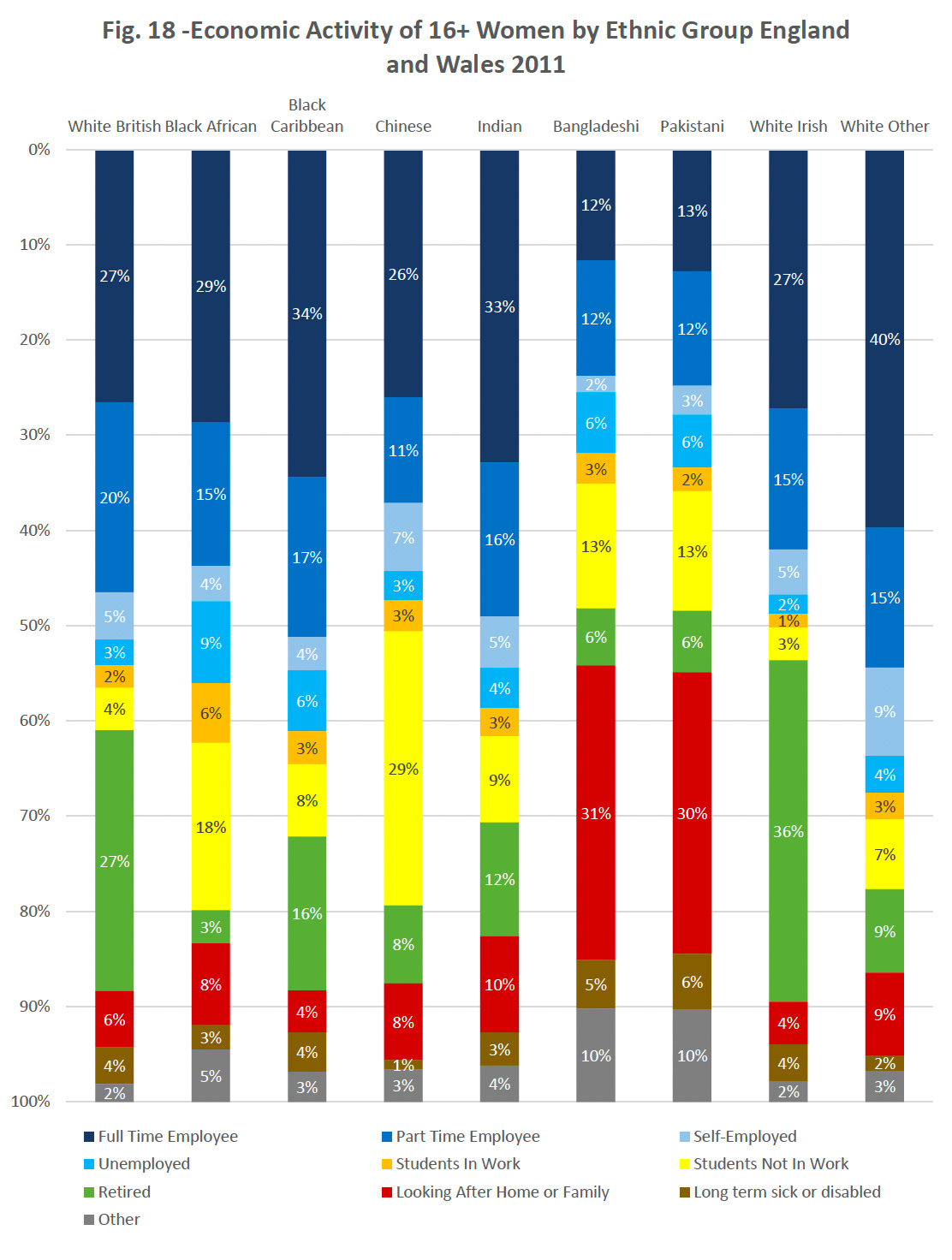

British Indian women also have high rates of full-time employment. This indicates strong labour market commitment.

Even in poor 1970s Singapore, Indian female economic activity was on par with Chinese and Malays. Across diasporic communities worldwide, Hindu women overwhelmingly work. This global pattern reveals something crucial: Hindu women’s low labour force participation in India is not driven by internalised religious ideologies - Hinduism does not mandate purdah.

Unlocking Caste Constraints

My globally comparative analysis suggests that Indian Hindu and Sikh women’s ultra-low labour force participation stems not from religious doctrine but from the persistent influence of caste-based status-seeking through Sanskritisation. Rather than narrowly relying on one tight-knit jati, the diaspora can build broader networks, doing business and forming associations with other Hindus and Sikhs.

This has crucial implications for policy. Interventions that weaken the salience of caste, reduce economic dependence on caste networks, or showcase high-status groups embracing female employment could help unlock higher female employment!

By directly tackling purdah-prestige and social policing, India could unlock the same transformation seen in Hindu communities worldwide, bringing millions of women into the workforce and driving economic growth.

How much of this is a bias in who goes oversees?

I don’t think this is a counter to the argument you’re making but a supplement.

Hindu women who emigrate are more likely to be from families that are less “bought in” on the cultural pressure to seclude women in the first place, and then go to places where their is less of that cultural pressure, and raise their children without that pressure.

Another way of putting it is that emigre populations are not representative of the populations they emigrated from.

Just a thought.

This is great work; if you want to extend it in the context of Women Indian architects and their anxieties of recognition, you could unpack the work of Madhavi Desai, which I think is highly patronising and an almost introductory critical stance by Dr Mary Woods in Women Architects in India: Histories of Practice in Mumbai and Delhi.

No caste is addressed in the discussions; that is the primary research gap. Then is how the discourse has been imported into the country from America. Diversity in America and India operates in two forms, which I think is not well understood, at least in the context of the ongoing gender discussions in the country.