Patriarchy is sustained by Traps and Trade-Offs

What is culture, and why does it persist? As an social scientist who has lived in communities across the world, listened to hundreds of life histories, and studied thousands of years of cultural evolution, I’ve iteratively finessed my theory of ‘culture’.

In this post, we’ll explore:

What are social norms? How do they impact behaviour?

The importance of neighbourhoods, norm perceptions, and rituals

The Patrilocal Trap

The Honour-Income Trade-Off

My perspective certainly departs from the conventional wisdom. Critique and comments are always welcome!

What are ‘Norms’?

Esteemed scholars have offered different perspectives:

Butler (2004) conceptualises norms as behavioural trends.

Pearse and Connell (2016) view them as ‘collective definitions of socially approved conduct’, not individual consciousness but ‘properties of a community’.

Swidler (1986) describes them as ‘tool kits’ of habits, skills, and styles.

Acemoglu and Robinson (2021) refer to them as ‘cultural attributes’.

However, these definitions don’t fully explain how widespread discourses, conventions, theological principles, and intersubjective meanings actually influence behaviour or motivate compliance. Why does anyone pay attention to a ‘cultural attribute’?

And what precisely are ‘norms’, if not reducible to mental states? As a erstwhile philosopher, I find this metaphysically unsatisfying! We need to clarify ontology and causation to explain why people challenge or conform to widespread practices.

Internalised Gender Ideologies and Norm Perceptions

Let us start with the primary drivers of human behaviour: beliefs and desires. Here, we can distinguish between distinguish between two key elements:

Internalised gender ideologies: An individual’s aspirations, stereotypes, and moral beliefs about what is right or wrong.

Norm perceptions: Beliefs about what is praised or condemned by others in a specific community.

This distinction is exemplified by Shah Rukh Khan’s film roles. His characters - attentive, respectful men who engage meaningfully with women - have earned him a massive fanbase. Many Indian women admire and desire such partners, yet as Shrayana Bhattacharya details, consider these relationships unattainable in real life. This disconnect between idealised portrayals and perceived social realities highlights the gap between internalised ideologies (wanting an attentive partner) and norm perceptions (believing such relationships are unrealistic).

Even if people are privately critical, they may nevertheless conform to what is widely praised in order to gain wider approval. This reinforces cultural persistence. Seldom seeing successful resistance, people may be despondent about the possibility of social change, and thus comply. But this creates a self-perpetuating cycle, inhibiting subversion. I call this a ‘Despondency Trap’.

How does change begin when the risk of social censure looms large? Since individuals only revise their norm perceptions after observing widespread behavioural shifts, how do societies break out of this coordination problem?

For variations on this theme, see

Community - where norms are learnt, unity is celebrated, and deviants are punished !

Observing social interactions in our communities, we learn what kinds of behaviour are esteemed and respected. These ideals are diverse and idiosyncratic, varying by community. Back in Kitwe, my Zambian mother taught me to greet every single trader at the market so as not to appear aloof. Whereas if I did the same in Patna (India), I might seem like a harlot. Travelling across Uzbekistan (where the fertility rate is 3.17), I was repeatedly encouraged to have a baby. No such pressure in Hong Kong!

Variation even holds at the level of individuals. Chatting with Acemoglu, I always feel free to spar and dissent, having seen that he always enjoys our spirited debates! For both Bihar and MIT, we develop norm perceptions of what is socially accepted. Heeding this contextual information, we learn and adapt.

But why do we even care what people say? Through empirical study, I identify two key drivers of desire for social approval: economic insecurity and group loyalty.

In poor communities, survival is highly dependent on network inclusion. Lacking social security, public pensions and formal employment, vulnerable to myriad shocks (ill-health and bad weather), community is imperative. Family is also valuable - the first port of call for help in a crisis. Economic dependence motivates conformity, since a wrong move jeopardises trust and risks ostracism.

That said, new research from neuroscience suggests our motivations aren’t reductively materialist. It’s not just about money. Social disapproval also hurts, psychologically.

Why does rejection hurt? Why do we care for inclusion?

Rituals: Reinforcing Group Bonds

We want peer approval, we want to be part of the group. This desire for inclusion isn’t innate, it’s actively built through collective rituals. Weddings, funerals, feasts, religious festivals, weekly worship, synchronised dancing, choral singing, and collective prayer all strengthen group unity, foster loyalty, trust, and cultivate shared identity. All these synchronous group activities trigger the release of dopamine, making us feel happy together.

For more on rituals, I strongly recommend the following books:

The ‘upside’ of bonding is that we develop trust, mutual care, and cohesion. Joe Henrich celebrates cultural learning as the ‘secret of our success’. But it also makes us much more sensitive to group rejection, which motivates conformity.

Let me illustrate with a personal example. My street has a WhatsApp chat, where we frequently share items, give recommendations, and help each other. It’s a very caring and cohesive community. This morning, the local council emptied our recycling bins. Everyone tends to bring in their plastic containers promptly, and I do likewise so I don’t look uniquely scruffy!

Social bonds thus reinforce desire for group membership, motivating strict conformity with what is praised in that community. By articulating this interplay between desires, networks and norm perceptions, we can understand the mechanisms of cultural persistence.

New Theoretical Frameworks on Gender

Recognising the importance of neighbourhoods and norm perceptions, let’s consider two persistent forms of gender inequality: marital abuse and low female employment. My empirical research reveals that each has different drivers, and requires a distinct theoretical framework:

‘The Patrilocal Trap’ - explains relationships within the family

‘The Honour-Income Trade-Off’ - concerns female employment and the wider world.

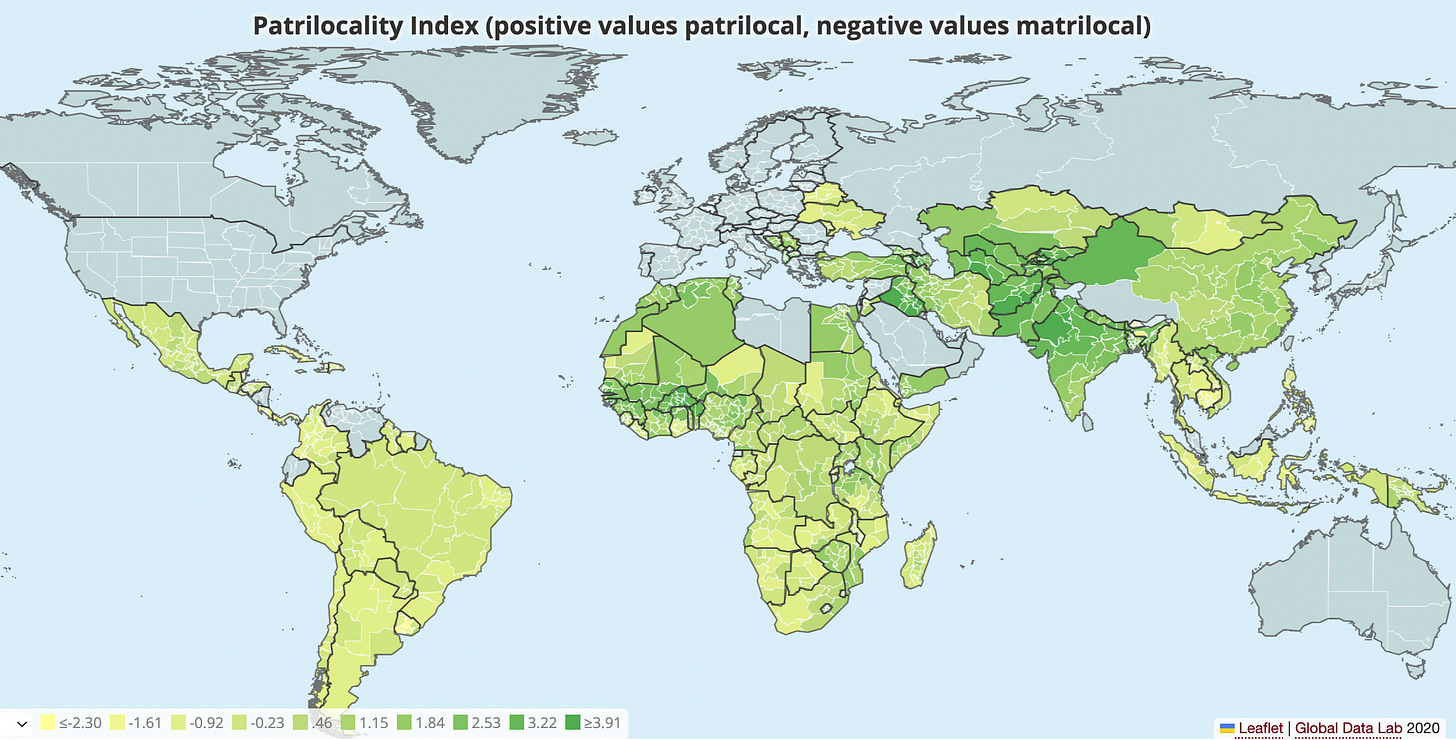

The Patrilocal Trap

In patrilineal societies, sons inherit wealth, perpetuate the lineage and perform ancestral rites. This specific system of kinship puts primacy on intergenerational loyalty. Growing up, children learn to put family first. In Karachi and Lahore, neighbours often say ‘paradise lies at the mother’s feet’. Bonds are also reinforced through rituals (like weddings) and living together in large families.

Now, marriage is necessary to reproduce the lineage, but also presents a threat - for a son who adores his wife may neglect other commitments. Mothers may feel especially insecure, fearing that beautiful young brides will steal their sons’ loyalty and support. His desertion spells her destitution.

To preserve patrilineal loyalty, mothers may actively sabotage their son’s marital attachment. She may actually stop them from spending time together.

If a couple seldom socialises, doesn’t go on fun dates, or enjoy shared rituals, they may grow apart. Lacking social glue, he may not necessarily empathise with her wants, nor feel remorse about violent attacks. A man who puts his mother on a pedestal may even allow her to abuse his wife.

Marriage is still imperative, however. Patrilocal societies secure trusted networks of cooperation through intermarriage. Natal families socialise their daughters to marry, stay put, and obey (as captured in Deepa Narayan’s excellent book, “Chup”). Divorcees are shamed and stigmatised. Concern for continued social inclusion means that families may actually discourage their daughters’ exit from abuse. Resulting inability to exit means that even if employed, women may still endure marital control and violence.

This is what I call ‘the Patrilocal Trap’. A woman’s weak position within marriage isn’t just a function of economic dependency. It must be understood as a patrilineal families teaching sons to uphold filial piety, suppressing romantic love, and stigmatising divorce. Let me show that visually:

‘The Patrilocal Trap’ helps us understand marital abuse and control, but it doesn’t explain low female employment. To address this, we need another framework: ‘the Honour-Income Trade-Off’.

The Honour-Income Trade-Off

In the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, and Central Asia, men’s honour depends on providing for their families and keeping their wives apart from unrelated men.

However, this cultural ideal doesn't exist in a vacuum; it creates significant trade-offs. The more women are secluded, the less they can contribute to household income. Families must then balance competing preferences: honour (achieved through female seclusion) and income (earned through female labour). This balancing act is what I term ‘The Honour-Income Trade-Off’.

In neighbourhoods where female seclusion is idealised, women's participation in the labour force responds weakly to economic opportunities. For instance, Suhani Jalota and Lisa Ho’s Randomised Control Trial in Mumbai found that slum-dwelling women poorly responded to well-paid office jobs.

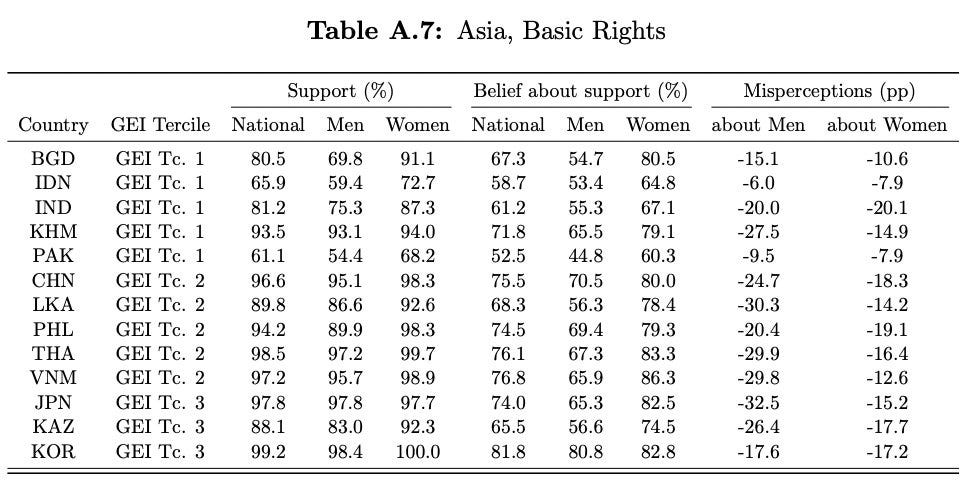

Norm perceptions play a crucial role in this dynamic. Only 55% of Indian men believe that their neighbours will support women working outside the home. Men’s concern for loss of honour means that they are reluctant to support their wives’ employment.

A husband’s attitudes to female employment then depends on the place-based characteristics:

Norm perceptions of what is esteemed in their community,

Economic opportunities and structural transformation.

If the only available jobs are low-paid and stigmatised (such as domestic work or manufacturing widgets with four men in a dark room in Dharavi), he may be extremely reluctant. Since a woman would only accept such conditions in utmost desperation, her employment would signal his humiliating failure.

Bosses may be equally reluctant. A Pakistani man who runs a restaurant, with five guys making delicious sweets, rotis and nihari, explained that he hesitated to hire a woman for he feared potential problems (i.e. harassment). Since most South Asian workers are employed in small firms, these risks of gender mixing loom large.

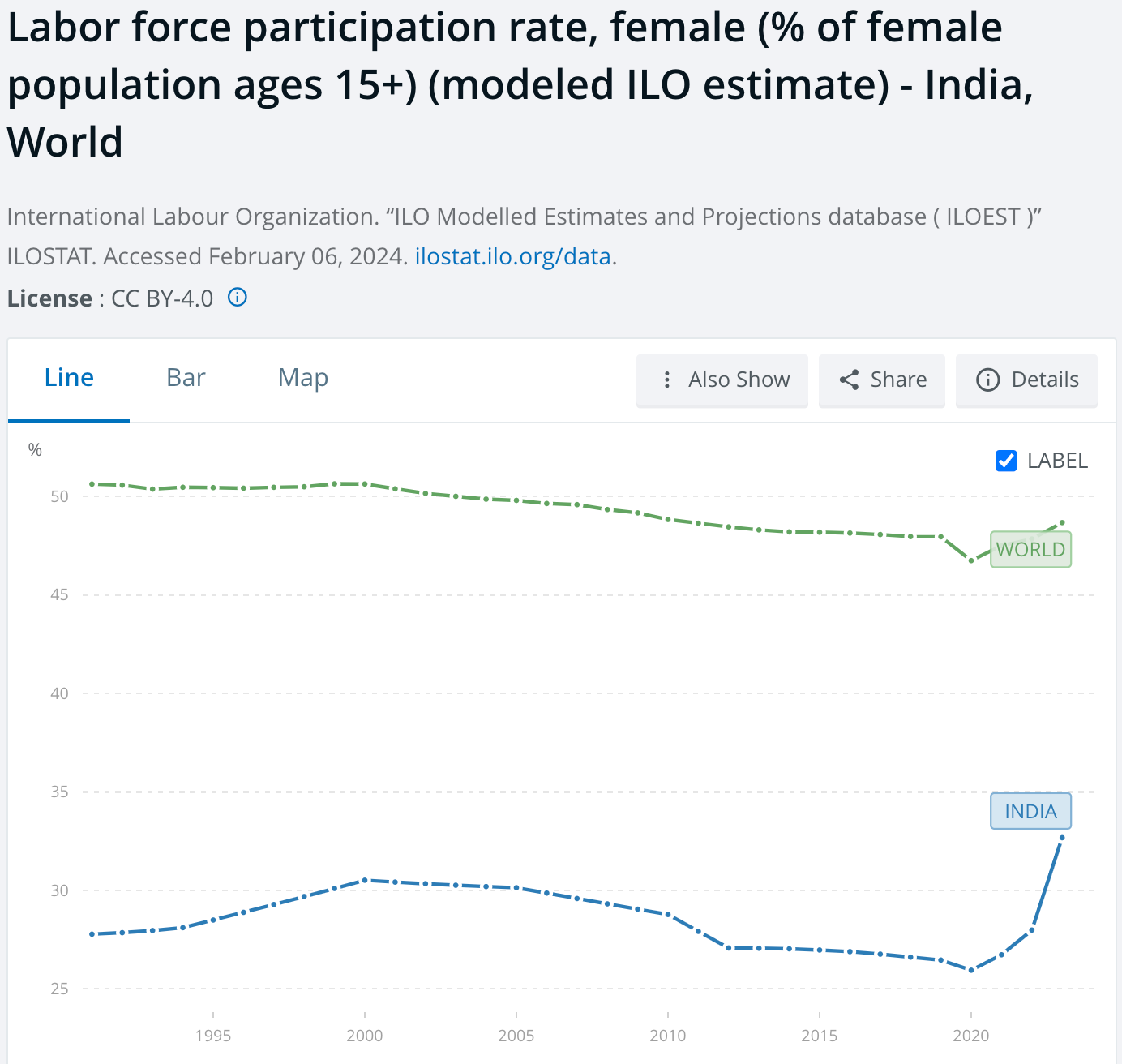

Low female employment isn’t just a function of the Honour-Income Trade-Off. It’s also a function of the Patrilocal Trap: if she has been socialised to obey and cannot credibly threaten exit. Combined, this explains why Indian female employment is well below the world average.

Each of these conditions are malleable, however! India’s female employment has recently increased, in line with rapid economic growth. This is precisely what my model predicts: a rise in respectable and well-paid jobs may compensate for preferences for seclusion.

Towards Gender Equality

Understanding culture as a combination of internalised ideologies and norm perceptions—both sensitive to context—allows us to better grasp the mechanisms of cultural persistence and change. As we grow up in our neighbourhoods, we learn which behaviours are praised or stigmatised. Through participation in collective rituals, we develop a desire for peer approval. Together, these factors motivate conformity to existing norms.

By distinguishing between the Patrilocal Trap (which explains a wife’s weak bargaining power within the family) and the Honour-Income Trade-Off (which elucidates low female employment), we can develop more nuanced strategies to address gender inequality.

To raise female employment, we can consider 3 key approaches:

Economic growth which increases esteemed, well-paid jobs.

Seeing one’s neighbours prosper may even induce materialistic competition and shift prestige bias, motivating stronger support for female employment.

Films, music and propaganda that shift norm perceptions, such that men believe female employment is widely respected:

Prime Minister Modi might say that the greatest service women can do for their communities is to seize jobs!

Pop music might celebrate women and men working together, building a strong India.

Bollywood films might flip the script and normalise female employment.

Effective policing, such that families do not fear their daughters will be raped. Today in India, every day is another horror story. As Kavita Krishnan details, this tends to heighten paternalistic protection.

By tackling these interconnected factors - economic opportunities, norm perceptions, and public safety - families may become more inclined to embrace female employment.

Effective policing, such that families do not fear their daughters will be raped. Today in India, every day is another horror story. As Kavita Krishnan details, this tends to heighten paternalistic protection.

---

You cannot have effective policing with SC/ST & reservations.

White men will tolerate Negro rape + single mothers.

We honor kill

ਅਕਾਲ

What do you think drives patrilineage vs matrilineage?