Why are So Many Latin American Women Beaten & Murdered?

Insights from Brazil, Part 1

For decades, Latin American feminists have rallied against intimate partner violence - decrying silence and demanding state protection. But why is the region such an outlier: why are so many women being beaten and murdered?

The standard answer is machismo, and of course this is a major motivation. But here’s the paradox: Latin America scores highly for gender equal attitudes, employment and representation - far above the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia. Yet it has much higher rates of femicides.

Drawing on my globally comparative as well as qualitative research in Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico, I suggest a resolution: Latin America is exceptionally violent. It accounts for 8% of the world’s population, but 36% of homicides. This drives up femicides.

Before sharing my analysis, let me stress that this is hugely indebted to activists, politicians, police officers, market traders, church goers, teachers, as well as men and women from the poorest favelas. Latin American connections kindly introduced me to their trusted networks. Friendships have been crucial - especially after my own attack in Oaxaca. Microsoft Translate has also been a great aid, enabling conversations in Spanish and Portuguese.

Patriarchy

Until very recently, men could abuse their partners with near impunity. Only in 1991 (after the fall of the dictatorship) did the Brazilian Supreme Court formally rejected ‘defense of honor’ as a legal justification for killing unfaithful spouses. Domestic violence continued to be seen as a minor offence, carrying a one-year sentence that could be converted to community service. Sustained feminist mobilisation has been vital in pushing governments to protect women.

Intimate violence may nevertheless persist - especially among family members who are emotionally attached, financially dependent and low status.

In Oaxaca, Mexico, I befriended three generations of women who sold tlayudas (crispy tortillas filled with cheese and vegetables) at a bustling market. Every female relative shared tales of intimidation and control. Chatting at their home, Mila (26) explained,

“Men regarded women as worthless; they thought women are their servants”.

In Puebla, I spoke with cleaners at a low-cost motel (where you drive into a central courtyard, then park by a room which is rented by the hour). Our conversations proved surprisingly popular: women even texted their friends, urging them to come chat, all using Microsoft Translate. One 55 year old cleaner shared,

“Mexican men are still very macho, they do not want to be surpassed by a woman. They should not be overcome. The man has to be always up, the woman down” (translated).

Chatting at a jewellery shop, Agnes (42, from a village near Querétaro) described both her parents’ and sister’s marriages as abusive. When accused of infidelity, her sister’s husband took the kids into the desert, threatening them with a long knife. Yet she did not leave.

Esther (52, who sells snacks at a small kiosk) described both her natal family and first marriage as patriarchal:

“My dad set the rules. He would have outbursts of anger without cause… My mother always said, “give attention to men”. My brothers always expected to be served… I never rebelled. I didn’t think it was wrong because my parents had instilled it in me… There was an ideology that from the time we get married until we die, then there’s just one person. But we aren’t realising that we are being mistreated. My friend was the one who realised I was being psychologically abused” (translated).

The most extreme case was narrated by Matteo, who runs a sandwich shop in Cholula. His grandmother was kidnapped, then bore 19 children. One time, her husband brought a girlfriend home and instructed his wife to cook for them. When she refused, he shot her in the thigh. She stayed married, hobbling.

Across Brazil, Costa Rica and Mexico, survivors explained that they had sacrificed for the sake of their children - “Darlo todo por los hijos”. Worries about stigma also weighed heavily (“¿Qué va decir la gente?” - what will people say?), since dirty laundry is ideally washed at home (“La ropa sucia se lava en casa”).

At a women’s police station in São Paulo, officers described how victims come to report abuse but then retract their complaints, trapped in what they called a “cycle of abuse”. Psychologically manipulative partners may manipulate them into self-blame - “gaslighting”.

Exit is no surety of safety, for it can also trigger backlash. In Mexico City, Carlos lashed out at Isabella when she tried to leave - furious at her defiance. In São Paulo, I repeatedly heard about gang members retaliating after breakups. Police described gruesome femicides where perpetrators deliberately disfigured victims’ faces, breasts, and genitals,

“so that no other man will have her” (translated).

Patriarchal expectations can be inherited. If boys observe their fathers being served food and speaking with authority, they may expect similar respect, and react aggressively when challenged. Indeed, Brazilian, Chilean and Mexican men who endorse patriarchy are more likely to report beating their partners.

Men whose fathers beat their mothers are also more likely to beat their wives. In Bolivia, 51% of men saw their fathers beat their mothers, while 42% were personally beaten.

In Latin America, a third of women become pregnant before turning 20. Teenage pregnancies can interrupt women’s education and reinforce dependency. Sonia (Brazilian) escaped her violent father to stay in the favela, became a domestic worker, then became pregnant at 14. After drinking, her boyfriend would inflict beatings and rape, yet she felt powerless to leave. Sonia’s second partner was also aggressive, and made her pregnant. Two children made it harder to pursue education and economic independence, especially since Brazilian schools end at 1pm. Neighbours never intervened, sustaining a culture of impunity.

Lara (57, now a hairdresser) grew up in a poor neighbourhood and at age 14 got a boyfriend. When she left 4 years later, he kidnapped and raped her. “He tried to kill me… No one wanted to protect me, nobody was sympathetic”. Lara missed her high school graduation. Her next partner was intensely jealous and controlling - insisting that she remain at home, constantly shielding her from other men.

The implication? If violence is primarily sustained by patriarchal ideologies, it will diminish with female employment, feminist activism and state protections for women. But is that the full story?

The Latin American and Caribbean Paradox

Now we come to a paradox. Latin America scores highly for gender equal attitudes, employment and representation - far above the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia. Yet it has much higher rates of femicides.

Within Latin America, even when countries (like Chile, Costa Rica and Brazil) have similar attitudes towards gender, they can differ enormously on femicides. This discrepancy suggests that something beyond machismo may be driving the murders.

Femicides are Higher in Violent Places

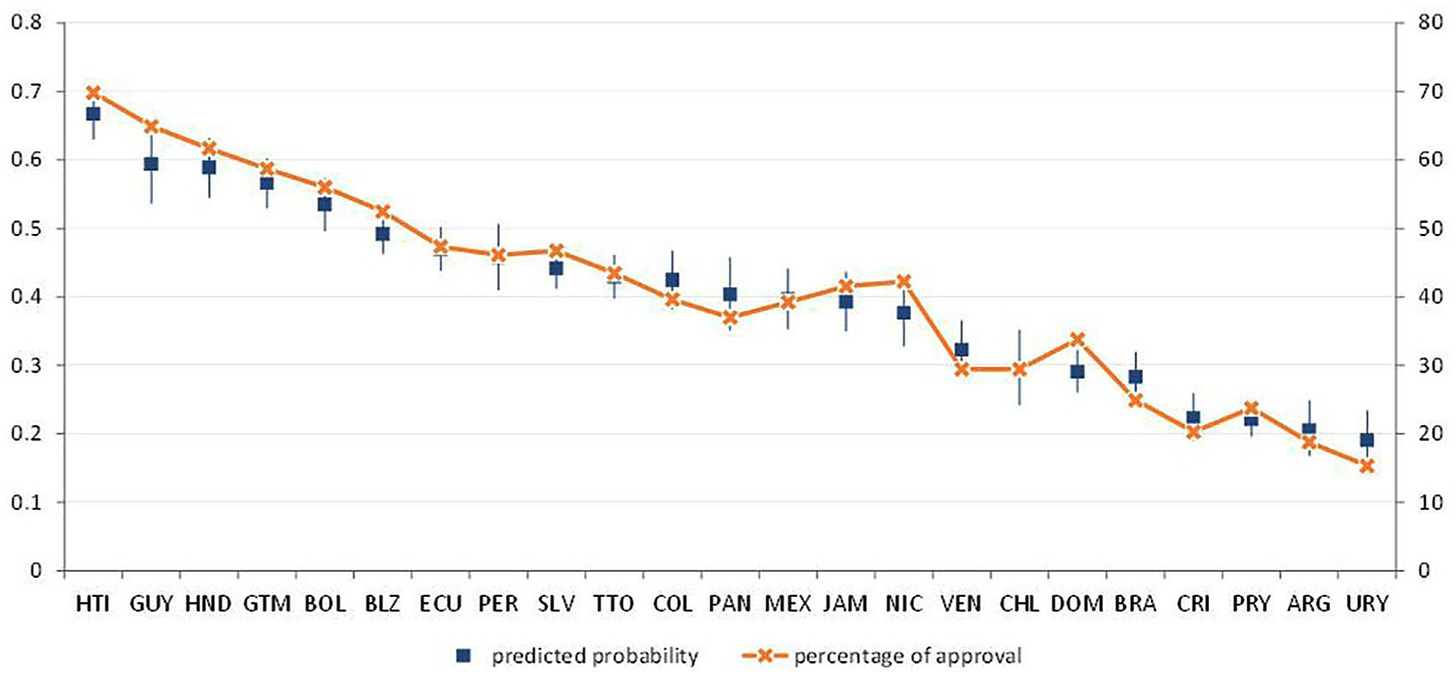

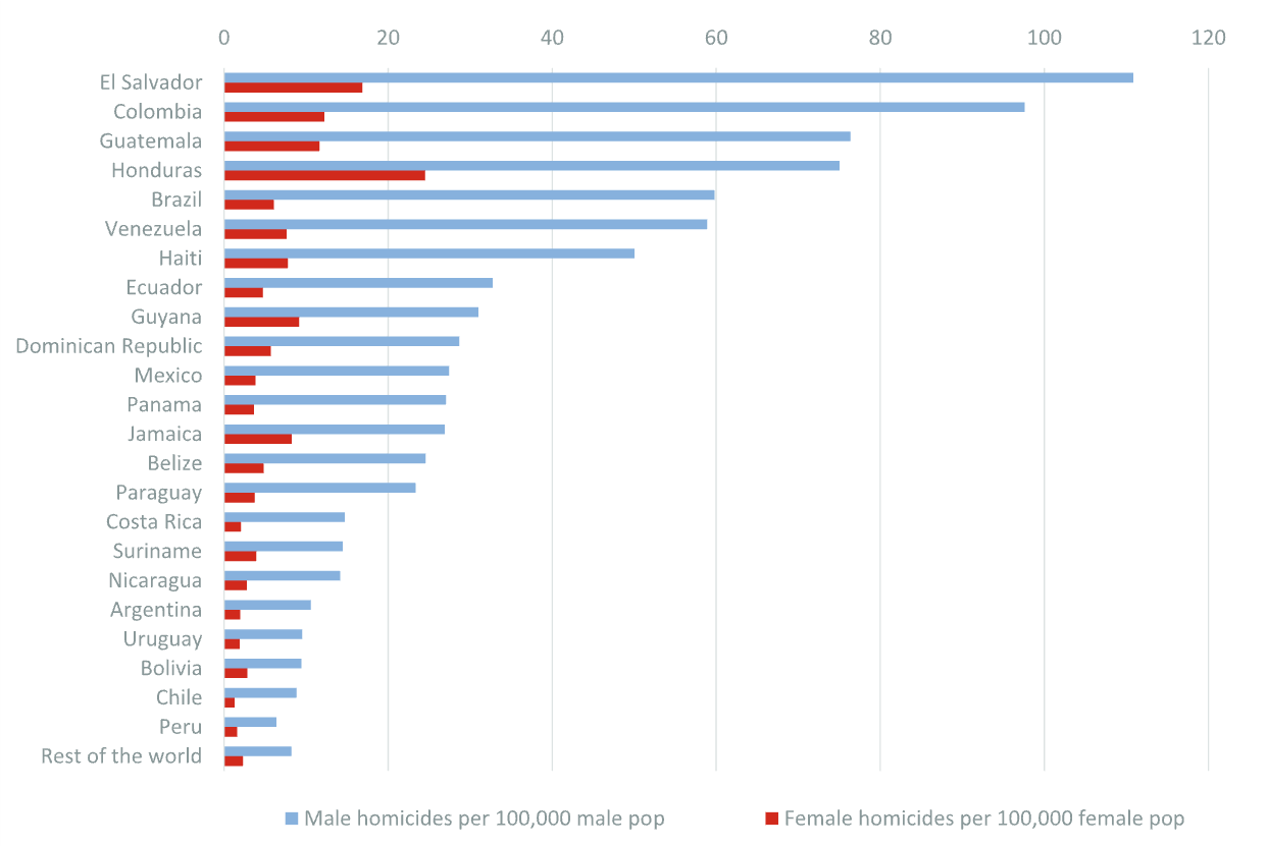

Globally, countries with more male homicides tend to have more female homicides.

Across Brazilian municipalities, the most significant predictor of female homicide rates in Brazil is male homicides. Other variables - like education, ethnicity, population size, and wealth - seem less important. From 2000 to 2018, Brazil’s rate of femicides actually fell by 14 percentage points. This was geographically concentrated in the Southeast - where there was a reduction in fire-arm homicide. In the Northeast - which is less developed, has a weaker state, more drug trafficking and higher homicides - femicides actually increased.

Tracking change over time, I find a close correlation between generalised violence and femicides. Between 2014 and 2022, Mexico’s male homicides increased from 17,506 to 28,244, while female homicides increased from 2,408 to 3,739.

Likewise, when drug gangs moved to Ecuador’s poorly monitored ports, homicides surged from 14 to 26 per 100,000 people between 2021 and 2022. Coastal cities simultaneously saw sky-rocketing murders of women. In Esmeraldas, killings per 100,000 women surged from 3.4 to 10.4.

While generalised violence usually elevates femicides, this risk is actually lower for Latin America and the Caribbean. Between 1995 to 2017, there were 0.194 female homicides for every male homicide in LAC, whereas for the rest of the world is was almost double. This suggests that the most important driver of femicides in Latin America is not an exceptionally sexist culture, but generalised violence.

Everyday Violence & Masculinity

In areas where the state fails to secure rule of law, violence becomes defensively necessary, habitual and even glorified. Men may cultivate a reputation for violence - for both self-protection and prestige. If peers and successful individuals gain kudos by toughness, young men may emulate this pathway to status.

Venancio (now 60) comes from Ceará (northeast Brazil) - where state presence is minimal and Catholic saints’ festivals incorporate indigenous rain rituals. Boys may be taught fearlessness by mounting an ox, while men typically carry knives. Unrestrained, Venancio’s father used to beat the entire family - one time whipping the cattle ropes against his son’s back.

In Southern Brazil, I was invited to visit a school serving a neighbouring favela. According to interviewed teachers, fights break out several times a week. Conflicts also erupt in class. Within minutes of my arrival, one student said to another, “I’ll punch you in the face” (translated).

A gay black man from another favela narrated his experience of violence - from his father’s beatings to school fights.

“I had be strong to show I was stronger. I wasn’t violent, but I had to be violent.

If you do something that affects someone’s masculinity, they’ll start a fight and that will become a murder. Everything goes around masculinity: the man needs to show their strength, their power, they’re reckless, otherwise they’ll treat him as weaker. That’s how things works, you need to learn how to use violence… Everything is about honour.

If you have a drug market, you need to control your territory, and if someone else comes you need to kill them.

Alice: How do men get honour?

Power, strength, women… you have one girlfriend, who’s ideally a virgin, and then multiple women, as many women as possible… [If a woman leaves] she’s showing he’s not man enough to keep her, but he thinks she’s his possession, he needs to punish her,

Alice: Do you think many Brazilian men have that same attitude?

Yes, many many, it’s not the majority but it’s enough to put the lives of women in danger”

Most striking? His nonchalant irreverence: “Death isn’t so bad, I’ve seen worse”.

A young man from Rio’s City of God [favela] shared that he was previously part of a pick-pocketing child-gang. At age 8, a drug trafficker stubbed a cigarette out on his face. The following year, his neighbour was publicly tortured. Since gang leaders ruled the roost, some youths belted out rap music celebrating dominance. Chatting over lunch, another favela-dweller told me that girls often sought thuggish partners [signaling protection]. Many of his childhood friends are now dead. When I confessed that I had never seen or heard of violence in my school or home-town, they were shocked by this cultural difference. “Not even school fights?”.

Online connectivity may heighten exposure. A black communist teacher (who had grown up in a favela) shared that exposure to violence isn’t limited to one’s personal interactions, but also includes viral videos:

“We see murders all the time. It is very common for us to see it nowadays with the internet.. In Brazil, our police kills the most in the world”.

Social media accounts also circulate videos of ‘levando um salve’ (punishments enforced by drug gangs or the community). The following show two thieves being beaten and women being shaved, with glue put on their heads. These portray the cartels’ vicious intimidation that many Brazilians vehemently abhor.

Intimate Partner Violence

“My brothers are married to women who obey them” - explained Sophia. “They have tempers, and their wives are afraid”. She added “Nowhere is safe for women in Brazil”.

Aggressive outbursts are not just individual idiosyncrasies, they are encouraged by cultures of violence. Across Mexico, Brazil and Chile, men who were beaten in their youth are doubly likely to abuse their wives. A man who abuses his wife is also much more likely to own a gun, participate in gangs and have a prison record.

Latin Americans are more likely to approve of a man who beats his wife if they also justify vigilanteism. In societies where extrajudicial killings are commonplace, men learn that it’s perfectly acceptable to project dominance. Prevalence and acceptance of intimate partner violence is lower in more pacified countries, like Uruguay.

Lyrically, Brazilian funk and Mexican reggaeton normalise violent retribution, especially for infidelity. DJ Helinho’s “Kit Salve Da Quebrada” threatens to break arms, bind bodies, and shave heads (1.4 million views).

Female funk performers are equally menacing: Mc Katia and Mc Nem’s “Duel 2” warn rivals with marks and bruises (5.3 million views), while Ludmilla’s “Fala Mal de Mim” vows beatings (5.8 million views). While we lack careful studies of causal effects on behaviour, I suggest that these widely-shared anthems reinforce expectations that disobedience will be met with violence.

In dangerous places, women may actually seek “strong and violent partners” - explained female police officers,

“He has to be strong.. They want only the strongest figure within the favela. Much as she may suffer some abuse, they also protect her from all others. At least it protects you from the rest…. The criminal occupies a position of power within the community. So violence and being against the law is a demonstration of masculinity”.

But such relationships are risky:

“Masculinity is to control this woman, so as not to lose possession. So, the greater the control he has over women, the more respected he will be in the community. If this woman does not respect him, he will also lose respect in the community”

“A man who is betrayed is seen as a joke, as a failure. So he can’t allow this humiliation, right? It’s male honour”.

Alice: If a woman leaves a man, is it as bad for his masculinity if he’s middle class?

“I think it’s the same. But it differs in communities where violence is a more immediate response, where he’s used to it, and the guy has less to lose”.

“If a man already has this culture of violence within the community, his response will be naturally violent”.

“Even the reaction of the people around it will be different. If a woman in the community shows up with a broken face, the neighborhood will not find it strange. No one will say, “let’s call the police”, because it’s common. But [in a middle-class neighbourhood] if you are in the elevator of your building, you see some woman with a broken nose, you will ask “What happened? Let’s go to the police, let’s do something”. The answer is different”.

Alice: So the man from the culture of violence is more likely, as you said, to respond with violence? Whereas the man with a job at the bank is also humiliated and angry but he cuts her credit card or something like that”.

(They nod in affirmation; translated).

Violence Begets Intimate Violence

Latin America and the Caribbean’s extractive institutions have primarily enriched elites. With pervasive corruption and limited fiscal space, public goods are under-resourced while policing is simultaneously brutal and ineffective. Undeterred, criminals battle for dominance - smashing up limbs and threatening their foes. Everyone is on guard, especially the most disadvantaged.

Back in the 1970s, some feminist anthropologists and archaeologists blamed patriarchy on states. Anti-statist discourse persists - even in top journals. More broadly, academic literature on gender rarely takes a comparative perspective, so omits underlying drivers.

My globally comparative, political economy analysis suggests a rethink: if feminists want to protect women, we need general security. Building on Stephen Pinker, as well as Acemoglu and Johnson, it’s vital to strengthen inclusive growth, effective policing and feminist activism so as to ensure everyone’s safety.

Methodologically, I hope to show the value of combining global comparativism, historical political economy, and qualitative interviews.

Stay tuned for my next essay on why Latin America has exceptionally high homicides, which drive exceptionally high femicides.

P.s. looking forward to visiting Santiago in October, please shout if you’d like to meet!

That is not Mexican reggaeton. Mexico does not produce reggaeton; mexico produces cumbias/corridos. Those artists in article are Puerto Rican and Colombian