Why is the Caribbean so Homophobic?

The Caribbean is notoriously homophobic, with dancehall anthems even encouraging people to burn ‘chi chi’ (gay) men. LGBT people in the region continue to face pervasive discrimination, stigma, and even death threats. What explains this intense hostility?

In recent years, a wealth of empirical literature has explored the origins and drivers of homophobia around the world. This essay examines studies from Australia, the U.S. Gold Rush, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the USSR, and explores their applicability to the Caribbean. Through this comparative lens, we will consider the legacy of:

Male-biased populations

Christianity, particularly Renewalist denominations

Political competition in democratic systems

Sexual violence as punishment in coercive institutions

Before delving into these potential hypotheses, let me briefly summarise contemporary manifestations of homophobia in the Caribbean.

Warning: This essay includes descriptions and images of torture in prisons, penal colonies, and slave plantations, as well as hateful song lyrics.

Violent Homophobia

Between 2009 and 2012, the Jamaica Forum for Lesbians, All-Sexuals and Gays (J-Flag), chronicled 231 cases of homophobic violence and discrimination.

Same-sex consensual intimacy is still criminalised in six Caribbean countries. In Jamaica, “the abominable crime of buggery” is punishable by imprisonment and hard labor for up to 10 years. Under the 2004 Criminal Code of St. Lucia, any act of “gross indecency” committed by people of the same sex is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. Any leader that sought to overturn this legislation would likely encounter backlash, since wider society is so homophobic.

This past week, I was fortunate to discuss this topic with people from Barbados and St. Lucia. ‘Nothing is more stigmatised than homosexuality’, one woman suggested.

Effeminate boys are bullied. Arthur, an 18-year-old gay man from St. Kitts and Nevis, recalled that his shamed family tried to hide his sexuality:

“I was not the most masculine of boys growing up, being called “anti-man” as a result by them…. [Whenever] I did something feminine [they would] jump on me… Mother was a very homophobic person, she asked me to change the way I talked and walked, I didn’t like it…. She knew [I was gay] and she was in denial [because of] her feeling embarrassed.”

Ernest, a 20-year-old gay man from Barbados, was beaten and ostracised:

“On one occasion my three uncles beat me up because of being gay. One was in front, one was on the right and one was on the left, and they beat me until I spat blood. They cut my face in all directions. I called my grandfather and he did nothing. After that my mother put me out. I was on the street for a night”.

Popular dancehall anthems routinely call for gay men to be executed. LGBT campaigners have likewise faced death threats. A gay man from the region shared:

“Every day I fear for my safety living in this country because of my sexual orientation. I am alive but if anyone ever find out and wanted to find out, they can kill me …I am an easy target for anything”.

To uncover the possible origins of this hatred, this essay examines the new empirical literature on homophobia, assesses competing explanations, and traces their applicability to the Caribbean context.

Australia's Convict History

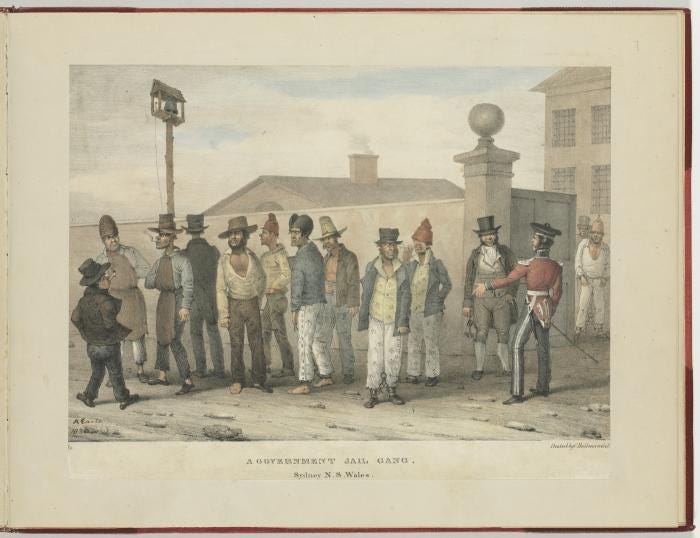

Between 1787 and 1868, Britain transported over 162,000 convicts to Australia. Crucially, these convicts were predominantly male - 132,308 men compared to only 24,960 women. Census data shows male convicts outnumbered women 28 to 1.

Importantly, these weren’t hardened criminals, but petty thieves and other minor offenders. Once in Australia, they were assigned to different locations based on labor needs rather than choosing where to settle.

Economists Victoria Baranov, Ralph De Haas, and Pauline Grosjean examined how this historical gender imbalance shaped local cultures and norms over the long term.

Violence and Aggression:

Areas with more male-biased convict ratios in the past now have 8.8% more assaults and 12.8% more sexual assaults.

Male Health Issues:

Male suicide rates are 20.2% higher in formerly male-biased areas, indicating less help-seeking behaviour among men.

Attitudes Toward Homosexuality:

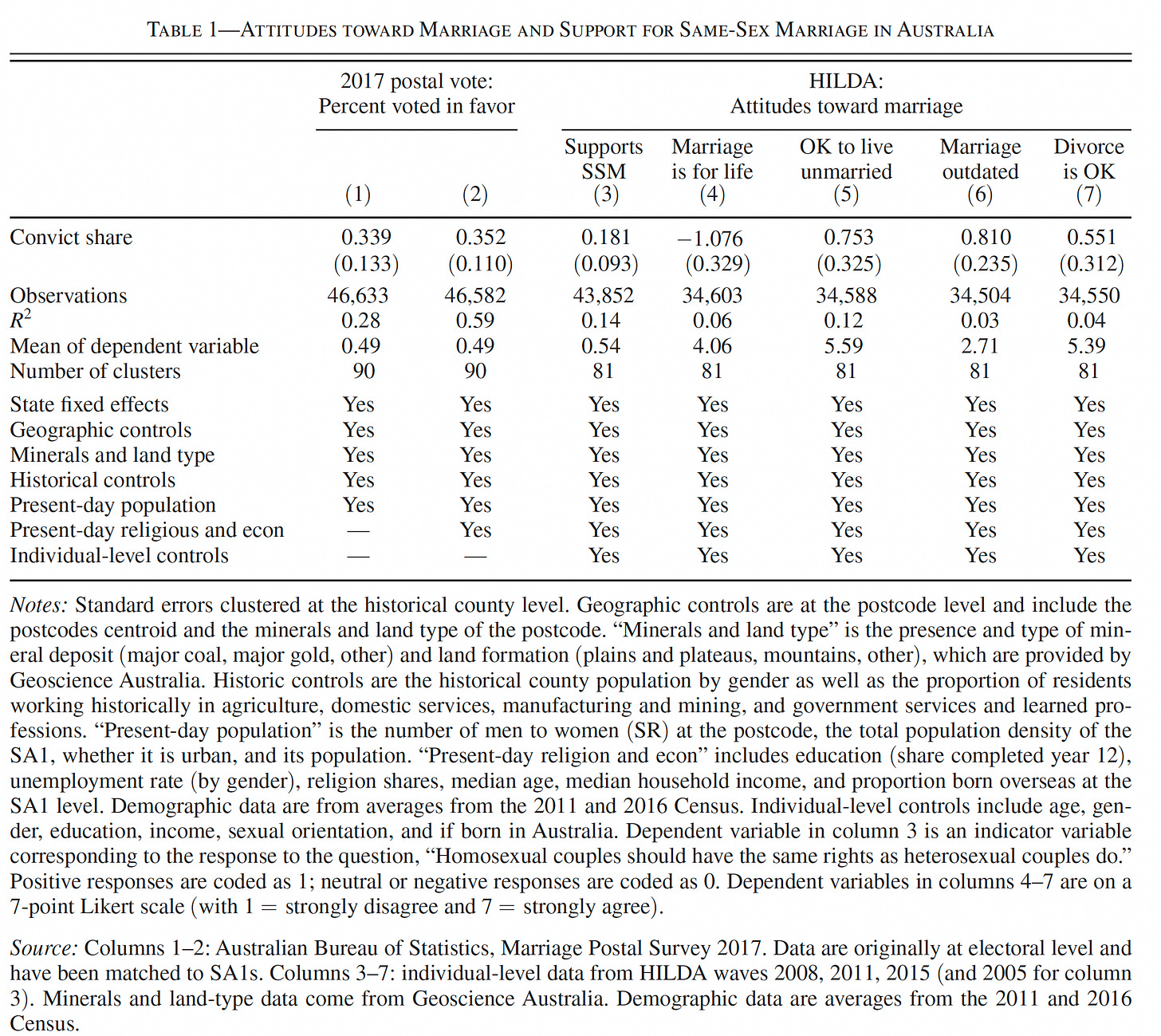

Perhaps most relevant to our question about Jamaica, the researchers found that areas with more male-biased convict ratios were significantly less supportive of same-sex marriage in Australia's 2017 referendum.

The authors interpret these findings as evidence that male-biased sex ratios fostered a culture of ‘hegemonic masculinity’ - an idealised form of manhood emphasising dominance, aggression, and heterosexuality.

Why did hypermasculinity and homophobia persist?

The authors point to the important of peer socialisation. Table 7 presents the results of regression analyses examining the relationship between historical convict sex ratios and bullying in schools in Australia. The key findings are:

A one standard deviation increase in the historical convict sex ratio is associated with a 3.6 percentage point increase in bullying of boys, as reported by teachers.

The same increase in historical convict sex ratio is associated with an 8.5 percentage point increase in bullying of boys, as reported by parents.

The effect sizes are substantial. For boys, the mean rate of teacher-reported bullying is 12%, so a 3.6 percentage point increase represents a 30% increase relative to the mean.

The regressions control for a wide range of factors, including geographic controls, historical controls, minerals and land type, present-day sex ratio and population, and child-level controls.

These results suggest that Australia areas that had more male-biased sex ratios during the convict era continue to have higher rates of bullying among boys in schools today. The authors interpret these findings as evidence of peer-to-peer transmission of masculinity norms, with bullying serving as a mechanism for enforcing and perpetuating these norms among boys. The fact that these effects are not seen for girls further supports the interpretation that this is related to masculinity norms specifically, rather than a general increase in aggressive behavior.

Class Variation?

More recent work by Baranov, De Haas, and Grosjean (2020) adds important nuance. Their study, “Queens of the Desert: Convictism and Marital Attitudes across Australia”, suggests that the class background of convicts may have had a liberalizing effect on social attitudes that persists to this day.

Australian areas with a higher historical proportion of convicts show more support for same-sex marriage and more liberal views on marriage in general in modern times. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in the local share of convicts is associated with a 7.4 percentage point higher probability of voting in favour of same-sex marriage.

When regressing initial conditions against contemporary attitudes towards homosexuality, they control for historic sex ratios. Baranov et al find that after controlling for this variable, the presence of convicts was associated with greater liberalism.

Convicts, coming from lower social classes, may have been less invested in enforcing strict marital norms and potentially more accepting of non-traditional relationships. This contrasted sharply with the attitudes of the colonial elite, who were deeply concerned about unmarried cohabitation and perceived homosexual behaviour among convicts.

Baranov et al argue that while male-biased sex ratios may have promoted hypermasculinity, the presence of a large convict population had a counterbalancing effect, promoting more liberal attitudes towards marriage and sexuality. This effect seems to have persisted through generations, with the strongest impact observed among Australians of local descent.

This is entirely possible. But are we overlooking other possible explanations..?

Alternative hypotheses

What about religious institutions? Priests may have been scarce in the Australian bush, or intentionally made convicts feel unwelcome?

What about forced labour? Convicts were shackled, put to hard labour in chain gangs, and frequently subjected to severe corporal punishment. Our analysis of penal colonies should not just focus on demography, but also recognise this violence and trauma.

Analytically, it may be impossible to isolate the effects of a male-biased population, compared to their treatment in coercive institutions. And that’s a key difficulty with studies on cultural persistence, by focusing on one aspect of an initial event, they risk overlooking synchronous activities and collapsing history.

US Gold Rush Paradox: When Male-Biased Populations Become Gay-Friendly

While our hypothesis suggests that male-biased populations can lead to increased homophobia, the case of the California Gold Rush presents an important counterpoint.

This historical event mostly attracted men, yet nevertheless seems to have encouraged same-sex marriage and gay-friendly attitudes. A recent study by Brodeur and Haddad (2021) offers valuable insights into the role of religious institutions in shaping long-term attitudes towards homosexuality.

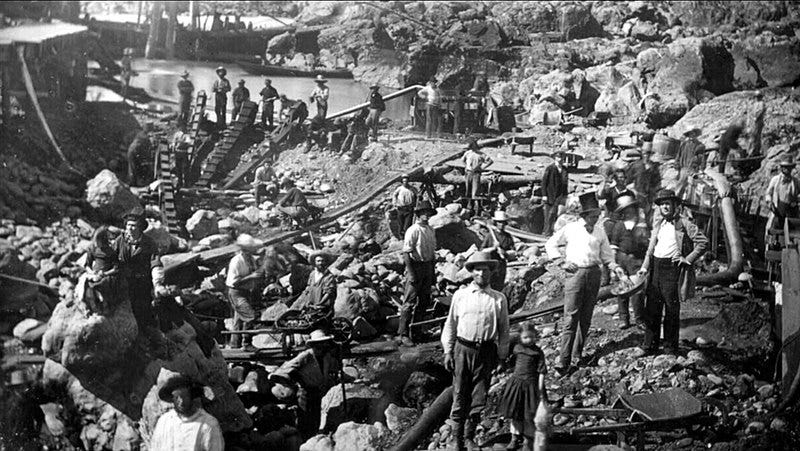

The California Gold Rush: A Natural Experiment

The Gold Rush of 1848-1899 led to a massive influx of predominantly male settlers to the American West. Men outnumbered women 7 to 1.

Brodeur and Haddad leverages this historical event as a natural experiment to examine its long-term effects on LGBT populations and attitudes. They find:

Counties which experienced gold rushes during 1848-1899 currently have about 15% more same-sex couples compared to other mining counties. This effect persists even after controlling for various geographic and demographic factors.

Residents of former gold rush counties display more favourable attitudes toward homosexuality in contemporary surveys.

Gold rush counties were initially isolated, mostly uninhabited, and crucially, lacked strong formal institutions, including Churches.

The Role of Religious Institutions

Gold rush counties were significantly less likely to have places of worship at the time of gold discovery. It took about 28 years after gold discovery for notable places of worship to be built in gold rush counties. In the absence of clerical interference, alternative social norms could take root!

Contrary to the Baranov paper, the Gold Rush suggests that demography is not destiny. Free from interfering clerics, male communities may have developed more tolerant attitudes towards same-sex relationships out of necessity or pragmatism. These attitudes then persisted.

Political Competition and Homophobia

Guy Grossman presents an alternative explanation of contemporary homophobia, by drawing on comparative research across Sub-Saharan Africa. Rather than stress historical antecedents, he emphasises how religious proscriptions are invoked for political legitimacy (which echoes my recent essays on the Muslim world).

Grossman finds that the political saliency of LGBT issues has been increasing unevenly across Sub-Saharan Africa in recent years.

He suggests this is closely related to two key factors:

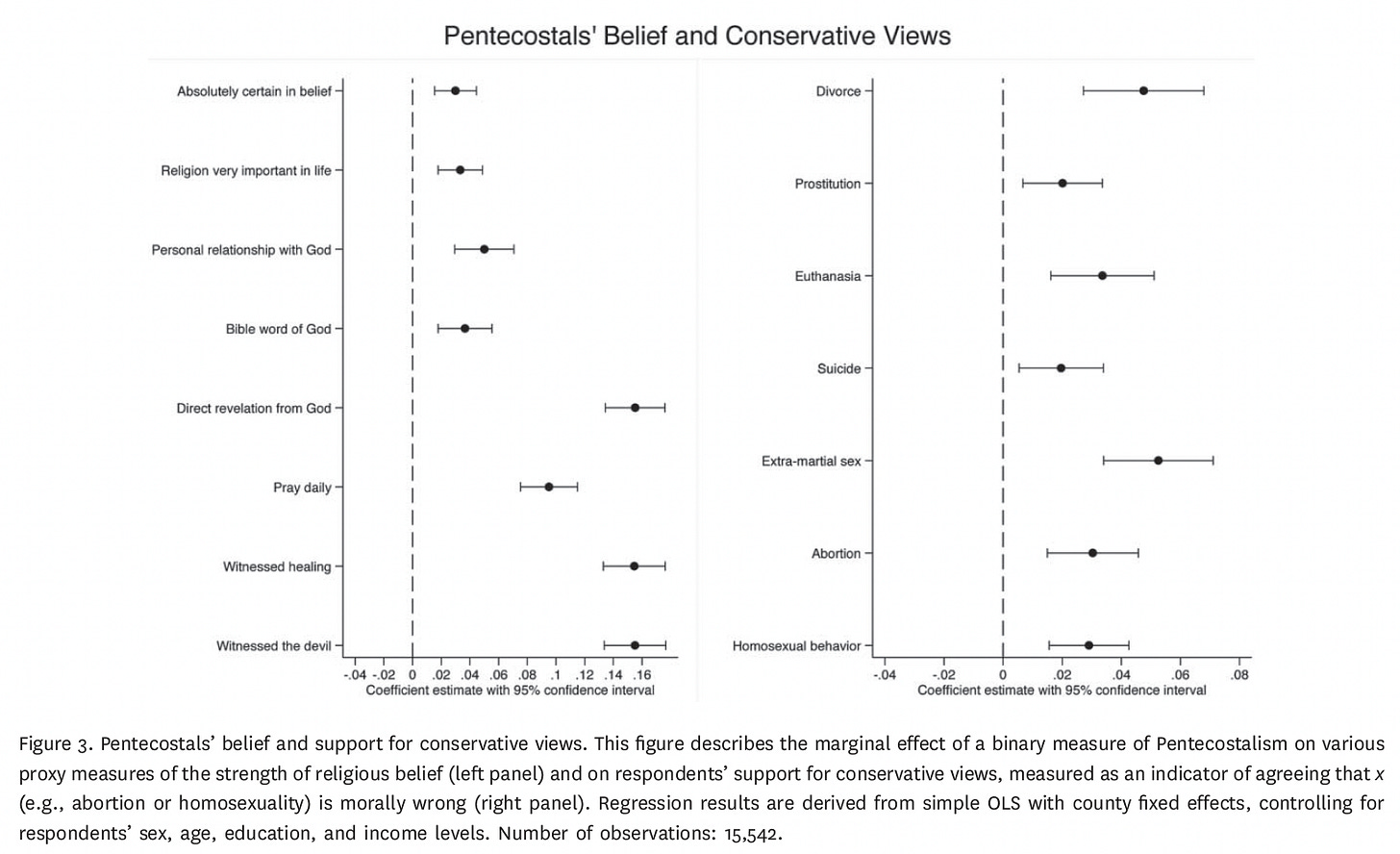

The rapid growth of Pentecostal, Evangelical, and related Renewalist Christian churches (which are especially homophobic), and

Democratisation processes leading to heightened political competition.

Politicians, especially incumbents, arguably find LGBT issues attractive because they offer a way to gain religious legitimacy, can mobilise voters through religious organisations, and are relatively easy issues to communicate and debate.

Grossman finds that LGBT saliency increases with a country’s population share of Renewalist Christians, and this effect is stronger in countries with higher levels of political competition.

This is an extremely compelling, and may well be applicable to the Caribbean.

Conservative Backlash?

Updating Grossman’s research, let me add that some African leaders have stepped up their condemnation of homosexuality. Last year, Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni, hosted an inter-parliamentary conference on “family values and sovereignty”, with representatives from 22 African countries. The event was promoted by the African Bar Association. Museveni declared,

“Africa should provide the lead to save the world from this degeneration and decadence, which is really very dangerous for humanity. If people of opposite sex [sic] stop appreciating one another then how will the human race be propagated?”

Museveni has also introduced an anti-homosexuality bill, which mandates a life sentence for “the offence of homosexuality”. In Kenya, Peter Kaluma MP has proposed a Family Protection Bill’, explicitly targeting LGBTQ+ funding or activities. Ghana’s parliament has just passed a new law that carries a prison sentence for up to three years for anyone convicted of identifying as LGBTQ+.

Speculatively, I wonder if this reflects conservative backlash to progressive discourses which are now globally visible (such as the opening ceremony of the Olympics). Google Trends data suggests a rise in searches for ‘LGBT’, especially in Kenya and Ghana.

Such cultural contestation echoes how Arab modernisers triggered religious organising in the 1960s, how progressive activism catalysed the USA’s Moral Majority, and how leftist agitation in Latin America increased support for right-wing authoritarianism.

Sexual Punishment and Shame

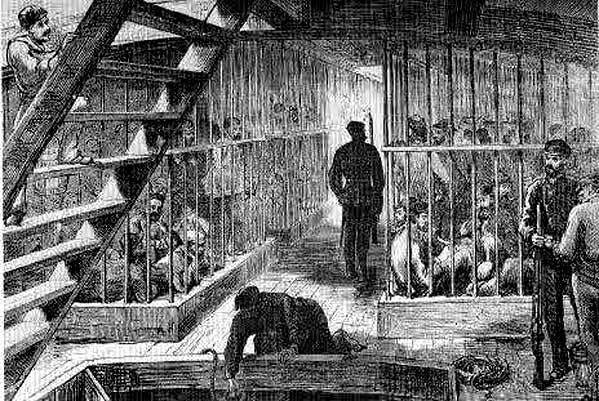

An alternative hypothesis comes from Maxim Ananyev and Michael Poyker’s research on Russia. In the Gulag system, a strict hierarchy emerged among prisoners, enforced through violence and sexual abuse. At the bottom of this hierarchy were the ‘petuhi’ (roosters), who were systematically raped and abused. This was a codified system of degradation:

Forced feminisation: ‘Petuhi’ were often forced to take on feminine names and perform traditionally female tasks, cementing their status as ‘not men’.

Ritualised rape: New arrivals or those who broke prison codes could be subjected to gang rape as a form of initiation or punishment.

Contamination rules: Any physical contact with a ‘petuh’ could result in an inmate being demoted to that status, creating a system of extreme social isolation for victims.

Guard complicity: Camp administrations often turned a blind eye or even encouraged this system as a way of maintaining control.

This system created a powerful association between male-male sexual contact and extreme degradation, shame, and loss of masculinity. As 60 million men cycled through the Gulag system, these attitudes spread.

Areas more exposed to the 1953 amnesty of Gulag prisoners show higher levels of homophobia today. Importantly, they find more crimes against gay men but not lesbians (which is consistent with punishment in prisons, rather than religious proscriptions). Also, the dispersal of prisoners did not change local sex ratios.

Ananyev and Poyker conclude that,

(i) family members of people who went through Gulag camps are more homophobic than others even when we control for the socio-economic and demographic factors;

(ii) exposure to amnesty also affected the preferences of people living in those locations that listen to prison life romanticization music;

(iii) and that the effect of the amnesty is largely mediated by the number of thieves-in-law coronations that embody the quintessence of prison culture.

Thus we conclude that the amnesty of 1953 increased intolerance toward gay persons through the spread of prison cultural norms.

Building on Ananyev and Poyker, I suggest that prison violence continues to perpetuate homophobia. Recent exposés have revealed widespread torture and sexual abuse in Russian prisons. In 2012, Sergey Savelyev, a former prisoner, leaked 40 gigabytes of prison videos and photos depicting systemic rape, ridicule, and beatings.

Putin's government has further institutionalised homophobia, positioning Russia as a defender of traditional values against a supposedly degenerate West. This has led to the extension of 'gay propaganda' laws and increased hate crimes against LGBT individuals.

The Russian case suggests that homophobia isn’t an inevitable reaction to male-biased ratios, but rather a function of institutionalised torture under incarceration.

Now let’s now consider how these factors - male-biased populations, religion, and sexual violence as punishment - may have contributed to homophobia in the Caribbean.

The Caribbean

From the 17th to 19th centuries, Caribbean sugar plantations relied on enslaved African labor. Plantation owners and overseers used a variety of brutal methods to control the enslaved population and maximise labor output. This system of slavery may have shaped contemporary attitudes towards homosexuality, but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Let us consider three possible hypotheses:

Male-biased populations: Plantations often had far more enslaved men than women. As in Australia, did these skewed sex ratios foster hypermasculinity?

Sexual violence as punishment: As in Soviet gulags, rape may have been used to punish and control enslaved men. Could this practice have created lasting associations between homosexuality and degradation?

Christianity: In the 19th century, missionaries converted many enslaved people. By 1838, when slavery ended in British colonies, about one-third of former slaves practiced Christianity. Did the introduction of conservative Christian morality play a decisive role in shaping attitudes towards same-sex relationships?

The following sections will examine each of these hypotheses in detail, analysing historical data and contemporary research to better understand the potential roots of Caribbean homophobia.

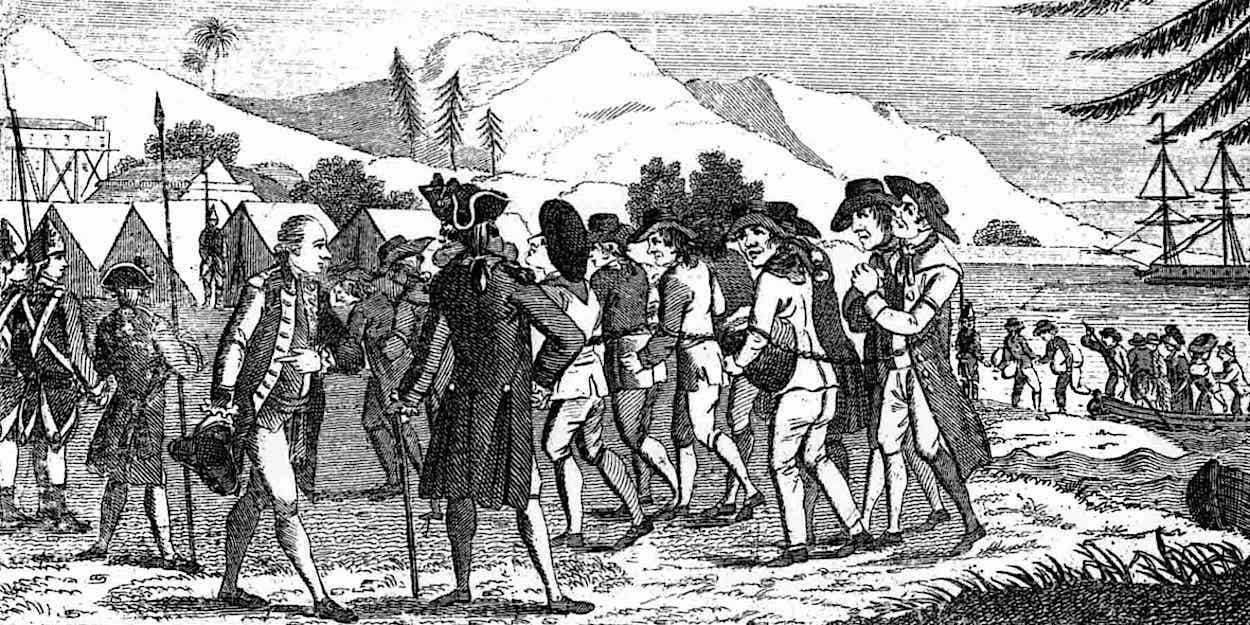

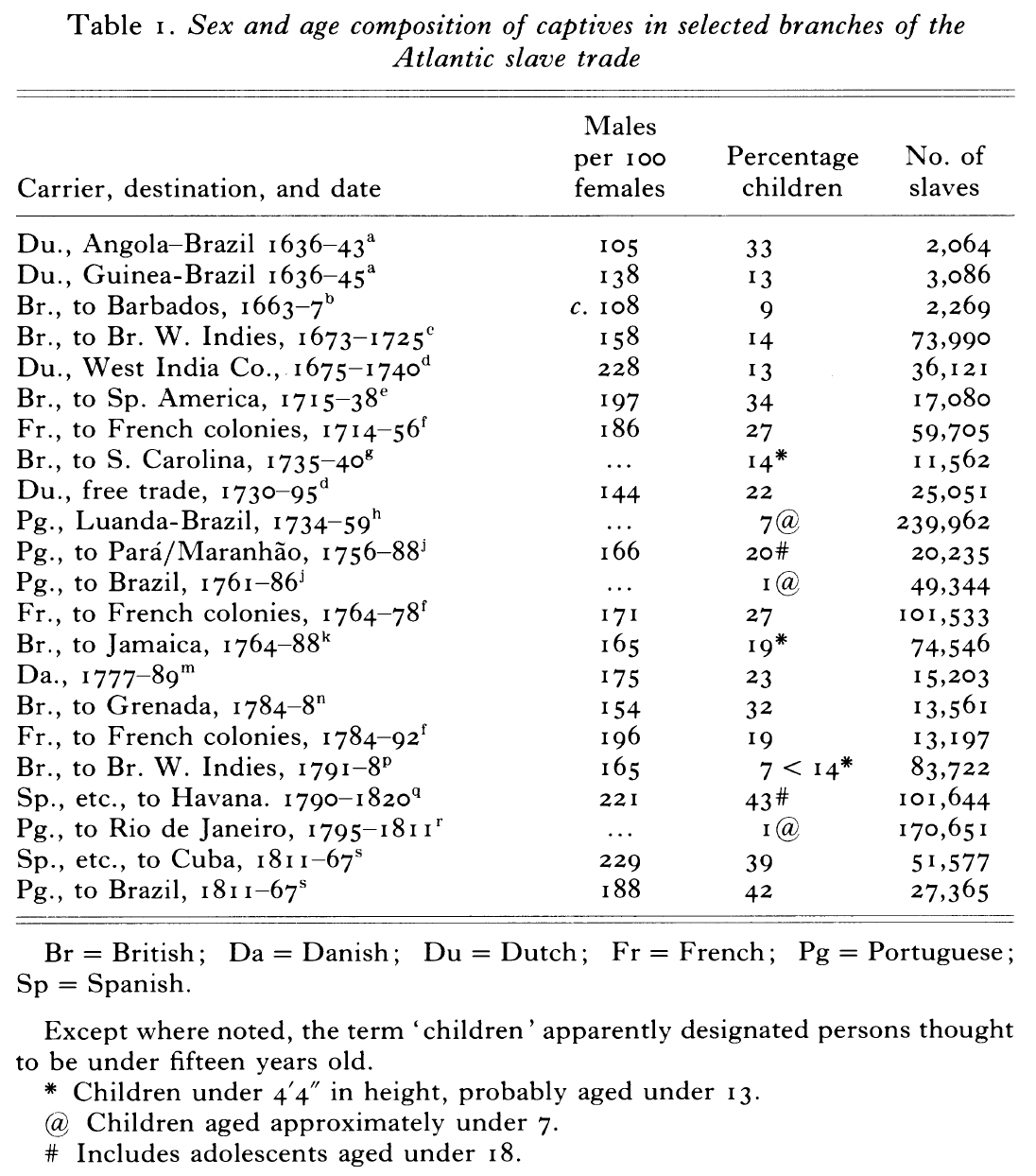

The Atlantic Slave Trade was Male-Biased

In 1820s, prices for prime males were about 110-130% of those paid for females - this reflected stronger demand for men. Cargoes of enslaved people were also heavily male.

Sugar plantations were often male biased

In British Honduras, the enslaved population was 163 males per 100 females. In the early 1800s Jamaica, nearly 10% of plantations had African male-to-female ratios exceeding 200 to 100. The gender ratios in Jamaica were far more skewed than in the United States, where by the 19th century, slave populations often had ratios closer to 105-110 men per 100 women.

After Britain abolished the slave trade, sex ratios evened up. In the late 19th century, the Caribbean actually had a deficit of men, owing to major male out-migration.

Churches

Christianity’s arrival in the Caribbean was intentionally delayed. Plantation owners actively resisted efforts to Christianise their enslaved workforce, owing to concerns it would undermine the racial hierarchy that justified slavery. They feared that baptised slaves might demand freedom or become more likely to rebel.

Quakers made early conversion attempts in the 1650s, but progress was slow. Anglicans initially restricted their services to whites alone. By 1725, Barbados had baptised only about 320 enslaved individuals, a tiny fraction.

The situation changed dramatically in the early 19th century, with the establishment of Anglican bishoprics in Jamaica and Barbados. Churches were charged with responsibility for education - to aid ‘civilisation’. By 1834, just before full emancipation, there were about 150 sectarian missionaries in the British West Indies. At this time, approximately 18,000 slaves were communicating church members, with a total of 85,000 ‘hearers or inquirers’ - about 11% of the total slave population of 776,000.

When full emancipation came in 1838, about one-third of the British ex-slaves were practicing Christians. Some missionaries reported significant numbers of conversions. For instance, Rev. G. W. Bridges claimed to have baptised 10,000 slaves in Manchester parish in just two years. At least three-quarters of the ex-slaves entered ‘freedom’ with ‘Christian’ names (given name and surname), often acquired through baptism.

Did Christianisation contribute to homophobia?

Churches were certainly heteronormative, and may well have reinforced pre-existing homophobia. That said, I have two reasons for scepticism:

The Gold Rush study found that areas which lacked religious institutions during their formative years developed more tolerant attitudes towards homosexuality. This persisted even after churches were established. Applying this logic to the Caribbean, we might expect that 200 years of plantation life would have been more than enough time for the emergence of gay-friendly norms.

Caribbean homophobia seems distinctively violent. By contrast, even when the U.S. was deeply religious, we did not see songs encouraging the incineration of gay men.

Dancehall Music: Homophobia Beyond Religious Influence

Dancehall, a genre dominated by young male artists, often features lyrics that are not just just homophobic but violent:

“Lick a shot inna a battyman head! Lick a shot inna a lesbian head! All sodomite dem fi dead, all lesbian dem fi dead” (Capleton, 1990).

“It's like boom bye bye inna batty bwoy head. Rude bwoy nah promote no nasty man, dem haffi dead” (Buju Banton, it’s specifically aimed at paedophilia, but this is often conflated with homosexuality)

“When yuh hear a Sodomite get raped/but a fi wi fault/it's wrong/two women gonna hock up inna bed/that's two Sodomites dat fi dead” (Elephant Man)

“I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays” (Beenie Man)

“Bun a fire pon a kuh pon mister fagoty, ears ah ben up and a wince under agony, poop man fi drown a yawd man philosophy” (Babycham and Bounty Killer)

These lyrics, with their explicit calls for violence and murder, go far beyond any traditional Christian teachings about homosexuality. They express intense stigma that may be rooted in something other than religious doctrine. Far from being shunned, these songs are massive hits. “Chi Chi Man,” about killing and burning gay men, was the Jamaican Labour Party’s 2001 theme song.

In 2004, J-Flag sought help from Peter Tatchell (then head of a British LGBT rights group). Together, they organised a media campaign, encouraging boycott of homophobic dancehall artists: ‘Stop Murder Music’. This laid the foundations for the Reggae Compassionate Act, which stated: “There’s no space in the music community for hatred and prejudice, including homophobia.” Beenie Man, Sizzla and Buju Banton signed on, while others refused. Subsequently, however, Buju Banton and Beenie Man retracted. Dancehall artists framed it as resisting former colonisers.

Given this exceptionally violent homophobia, which goes far beyond traditionally Christian teachings, I suggest we revisit the exceptional horrors of plantation slavery.

Sexual Punishment during Slavery

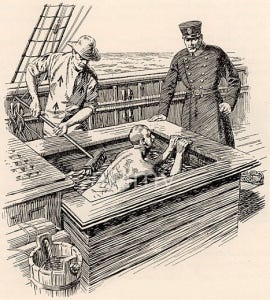

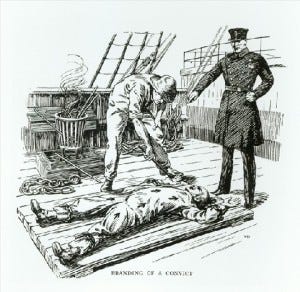

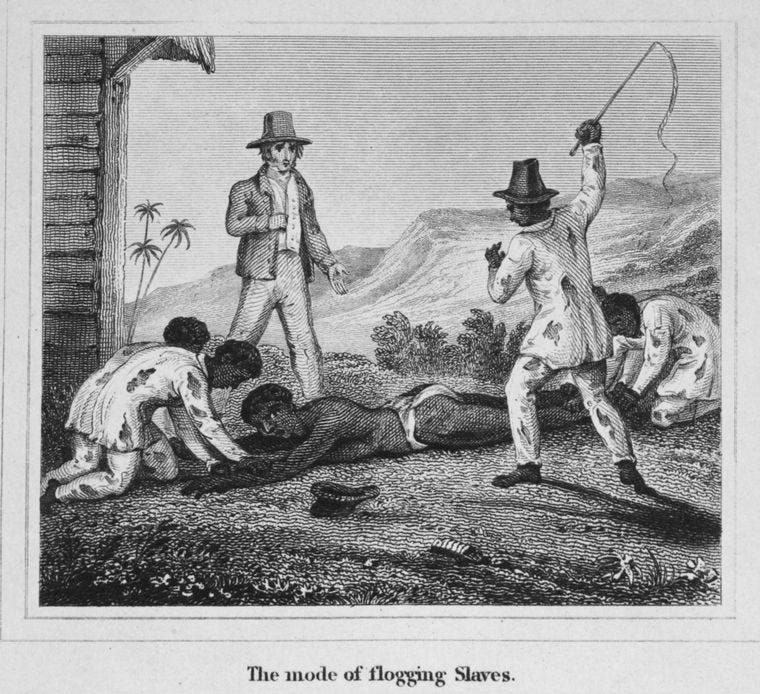

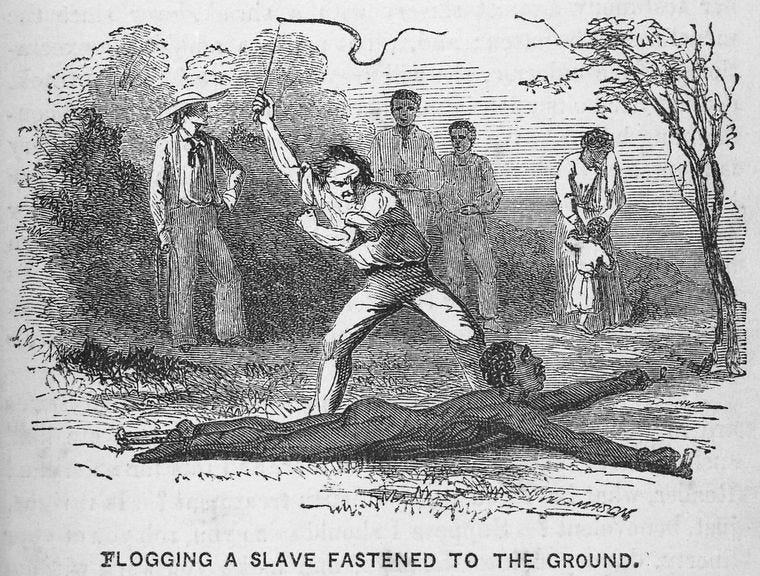

Punishments included whipping, which was often administered publicly to instill fear in other slaves. Some plantations had dedicated ‘punishment books’ detailing the whippings and other tortures inflicted on enslaved people. More severe punishments included mutilation, branding, and prolonged confinement in stocks or dungeons.

Slave rebellions were met with particularly harsh reprisals. Following the 1760 Tacky’s Rebellion in Jamaica, captured rebels were burned alive or gibbeted (left to die in iron cages). Even after the official abolition of slavery, the apprenticeship system (1834-1838) maintained many of these coercive practices.

In an article in the Jamaica Observer, John Hardy wrote:

"The black slaves and most of their descendants developed this hatred for homosexual activities because of the painful experiences that their forefathers endured during slavery.

It is alleged that if and when a white slave master suspected that black male slaves were showing any sign of resistance to their enslavement, the most cruel and brutal treatment would be meted out to them. One such treatment would be sodomisation."

This practice was not unique to the Caribbean. On U.S. plantations, sexual violence against enslaved men may have been used as a tool of domination and emasculation. In "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl”, abolitionist Harriet Jacobs alluded to a crippled slave-master (named Luke) meting out sadomasochistic punishment:

“The fact that he was entirely dependent on Luke’s care, and was obliged to be tended like an infant, instead of inspiring any gratitude or compassion towards his poor slave, seemed only to increase his irritability and cruelty. As he lay there on his bed, a mere degraded wreck of manhood, he took into his head the strangest freaks of despotism; and if Luke hesitated to submit to his orders, the constable was immediately sent for.

Some of these freaks were of a nature too filthy to be repeated. When I fled from the house of bondage, I left poor Luke still chained to the bedside of this cruel and disgusting wretch”.

In his new book, “Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men”, Thomas Foster draws on a range of sources (newspapers, court records, slave owners’ journals, abolitionist literature, former slaves’ testimony) to suggest that enslaved black men were sometimes sexually violated.

When enslaved men were sold, their bodies were often stripped and scrutinised. Once deployed in coercive plantations, men were publicly humiliated and emasculated. In his 1862 account of enslavement in South Carolina, John Andrew Jackson details:

“On one occasion I saw my brother Ephraim tied up and blindfolded with his own shirt, and beaten with fifty lashes before his own wife and children, by a wretch named Sam Cooper, because he was falsely accused of having stolen a yard of bagging.”

“Fathers! think of being tied up and stripped before your wife and children, and beaten severely for nothing at all; and then think that it is a daily, nay, hourly, occurrence in the Slave States of America, and you will begin to have some idea of what American slavery is.”

Men were not only tortured, but publicly stripped and degraded in front of the wider enslaved community. Slavers and overseers sometimes intentionally injured men’s genitals. In Maryland, one African American detailed that after a severe beating with a hickory paddle, his ‘privates were very much injured and swollen very large’. Whipping was sometimes so severe that it pained men to redress. In 1853, a ‘Louisiana overseer nailed an enslaved man’s penis to a bedpost as part of his punishment’.

Sadomasochism was extreme. Enslaved men were sometimes psychologically tortured through forced participation in sexualised punishment, such as being compelled to defecate in another man’s mouth, or castrate another. As Orlando Patterson has famously argued, this was ‘social death’. At every step, men were degraded.

While direct documentary evidence of sexual violence against enslaved men is limited, the historical record clearly demonstrates plantation slavery frequently included rape of enslaved women, forced breeding, and various forms of physical torture.

Given slave owners’ the totalitarian control, pervasive violence and routine humiliation, it is possible this also included anal rape. The paucity of written records may be due to extreme stigma and the scarcity of slave narratives.

I hypothesise that sexual abuse of enslaved men may have been especially pervasive in Caribbean plantations, which were majority male. Since women were scarce, enslaved men may have been used as sexual substitutes. The possibility of this degrading form of torture loomed over all enslaved men, creating a pervasive atmosphere of fear and shame associated with male-male sexual contact.

Why is the Caribbean so Homophobic?

Empirical studies from the U.S., USSR, Australia, and Sub-Saharan Africa point to several possible mechanisms that can shape attitudes towards homosexuality: male-biased populations, sexual torture, religious institutions, and political competition.

I hypothesise that their interaction may have contributed to the region’s intense homophobia. Degrading, emasculating sexualised violence in male-majority plantations may have fomented shame. These may have been reinforced by the growth of churches and democratic competition, where politicians might exploit anti-gay sentiments for electoral gain.

To test this hypothesis and further our understanding of Caribbean homophobia, future research could examine:

Historical parish-level data on slave population sex ratios and punishment, correlating these with contemporary homophobia.

The growth of Renewalist churches in different Caribbean countries and its relationship to levels of homophobia.

The relationship between political competition and the promotion of homophobia.

Mechanisms of cultural transmission, such as dancehall music lyrics and bullying of effeminate boys.

International reactions to progressive discourses on LGBTQ+ (just like this paper on the German AfD).

Post-script:

My second book will be on “The Great GAY Divergence”. Academics, please keep me posted if you have new papers on related themes. Critique and feedback is always welcome, especially from people who live in the societies I try to understand.

Next up, I am writing a forthcoming essay on how plantation slavery destroyed family bonds, contributing to single mothers.

Over the upcoming months, I’m excited to visit Thessaloniki, Budapest, Kuala Lumpur and Jeddah. Get in touch if you’d like to meet.

Further Reading

Abel Brodeur, Joanne Haddad, “Institutions, attitudes and LGBT: Evidence from the gold rush”

Thomas A. Foster, 2021. “Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men”

Orlando Patterson, “The Sociology of Slavery: Black Society in Jamaica, 1655-1838”

Orlando Patterson, “Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study”.

Fascinating as usual, Alice.

A few observations:

Consistent with your slavery effects hypothesis, my island of Saba is both the most LGBTQ-friendly Caribbean island by a very wide margin, and also has a very different history with slavery than most other Caribbean islands, because it’s too steep, rocky and has too poor of soil to allow for monoculture agriculture. These conditions allowed for subsistence farming, but not for profitable crop production on Saba—meaning slavery wasn’t profitable here, either.

A good comparison to test this hypothesis would be to compare Saba (pop. 1900) and St.Eustatius (pop. 2700), which is 16 miles away, also a Dutch special municipality, comparably religious, but St. Eustatius was a major slave-trading way station.

Also, while there are Dancehall songs that endorse homophobic violence, anal sex (with women) is absolutely celebrated in many Dancehall and Soca songs. A Caribbean denunciation of “sodomy” may be condemning homosexuality, but that also could be read as criticizing the popularity of heterosexual anal sex.*

Finally, you seem loathe to attribute any of the Caribbean’s homophobia to importation of West African cultural values—but West African cultures are also very homophobic and endorse violence against gay people. You tie that African homophobia to the influence of modern Christian movements there, but isn’t it likely that anti-gay religious teachings took root because of an underlying anti-gay culture? Enslaved west Africans brought to the Caribbean could have brought more deeply anti-gay attitudes with them, and have that influence today’s culture, in the same way that west African rhythms influence Dancehall tunes today.

Also I thought I should mention: The influence of Indian (here meaning Asian Indian, not indigenous Caribbean) culture on Caribbean culture is underappreciated by people who don’t live here. But many indentured servants from India were also imported to the Caribbean, obviously influencing food culture (this is why there are so many curries in Caribbean cuisine) and surely influencing other aspects as well. I don’t know if you want to pursue that line of inquiry when you’re looking into the homophobia of the Caribbean, but I think it’s worth considering.