Culture isn't a Fossil, it's a Fistfight

Culture is not a static inheritance, but a dynamic arena of ongoing struggle. From the mosques of Jakarta to the classrooms of Louisiana, from TikTok feeds to university lecture halls, ideological warfare rages. This essay explores the complex interplay of several crucial factors shaping our cultural landscape:

Contestation: Culture is a battlefield where competing ideologies clash, merge, and evolve. Prestigious actors and institutions are especially influential, as others look to them as successful. No norm is set in stone; instead, we see a perpetual push and pull between progressive and conservative forces, each vying to define societal values.

Economic growth, technological advances and political freedoms do not entail cultural liberalisation. These are merely vehicles - to be used by progressives and conservatives alike.

Religious and cultural traditions: Deep-seated beliefs shape the receptiveness to change, and the scope of public debate.

Drawing on my qualitative research across nine world regions and evidence from multiple disciplines, this essay examines ideological battles in diverse settings, from the United States to the Middle East, Southeast Asia to Latin America.

The path of cultural change is neither linear nor predetermined; reformers navigate the fine line between pushing boundaries and triggering conservative resistance

US Culture Wars

The United States offers a compelling case study in cultural transformation, with dramatic shifts occurring over just a few decades.

During the McCarthy era of the 1950s, the US government persecuted liberals in Hollywood through blacklists and congressional hearings. This state-led repression caused American films and attitudes to become more conservative.

Liberals pushed back and overturned state censorship. Building on America’s secular foundations, the 1960s Counter-Culture movement rallied against the Vietnam War; while Rock and Roll music celebrated a spirit of rebellion; and hippies got loose on recreational drugs. This culture of youthful resistance was enabled by job-creating economic growth, universities, democratisation, and secularism. The Church had lost legitimacy.

‘My body, my rights’ - yelled feminist activists. In consciousness raising groups, university students queried patriarchal expectations. They sought sexual and bodily autonomy.

Television then played a crucial role in popularising cultural revolution. Network executives were not woke pioneers, they were just competing for market dominance. Eager to get tongues wagging and attract viewers, producers introduced more progressive and salacious content. Instead of portraying nuclear families, sitcoms focused on workplaces, bars, romances, friendship circles and female action heroes. As Gloria Steinem wrote, “Wonder Woman” celebrated female strength and self-reliance: a woman could fight men and win.

Initially, executives were unsure about public reactions. ABC executive Barry Diller rejected the concept of “Charlie’s Angels” saying, “Three beautiful girls running around doing male things, chasing criminals. It's not believable”. The show’s eventual success - securing 59% of all TV sets in use during its slot - proved him wrong and paved the way for more female action heroes. NBC and CBS took note, given its commercial rewards.

Networks’ hesitation reflected wider social conservatism. If people grow up in communities where women are always portrayed as demure and domesticated, they may underestimate support for alternatives. Breaking the mould is often unthinkable.

Television had the power to show audiences something entirely different - and even make it enjoyable. “Mary Tyler Moore Show” (1970-77) became an icon of what Economist Claudia Goldin calls the “The Quiet Revolution”. Its protagonist, Mary Richards, was a single career woman navigating professional and personal challenges in Minneapolis. The show’s theme song began with the poignant question, “How will you make it on your own?” - a query that resonated with millions of women seeking independence. “One Day at a Time” (1975-85) broke new ground by featuring a divorced mother raising two teenage daughters on her own.

By presenting alternative lifestyles and career paths for women, television helped reshape societal expectations. Viewers, seeing relatable characters succeeding in non-traditional roles, began to question and challenge existing gender norms. As one fan explained,

“MTM [Mary Tyler Moore] first gave me the idea that you can own your own show and produce it. She was the one. She paved the way through storytelling for women.. and was a value system for women”.

Her name was Oprah Winfrey.

Conservative Backlash

Conservative groups, alarmed by what they saw as a threat to traditional values, then organised in resistance. Organisations like the National Council of Catholic Bishops protested against TV shows that dealt with controversial topics like abortion. A specific example was their protest against an episode of ‘Maude’ that dealt with the topic of abortion, which they saw as promoting immoral behaviour.

The National Federation for Decency joined forces with the Moral Majority to form the ‘Coalition for Better Television’, aiming to pressure networks into more conservative programming. They organised boycotts of sponsors of shows they deemed offensive, attempting to use economic pressure to shape cultural content.

Laws, like the Equal Rights Amendment, also triggered resistance. As Brian Wheaton shows, after a state passed the ERA, the share of men expressing support for gender equality dropped by 15 percentage points.

Cultural change is never a one-way street. Each progressive push triggered countervailing mobilisation, creating an ongoing tug-of-war.

The Jewish Enlightenment

Judaism and Islam share significant theological similarities, particularly in their emphasis on strict codes enforced by threats of punishment. In both traditions, men were given religious primacy. Just as Jewish men are obliged to study the Torah, Muslim men must attend Friday prayers. Women’s access to religious spaces was often restricted; for instance, women were not permitted to enter Herod’s temple.

Both Judaism and Islam share detailed prescriptions for daily life, including rituals, dress codes, dietary laws (kosher for Jews, halal for Muslims), and the practice of male circumcision. Both also traditionally prohibited image-making and the consumption of pork. These similarities reflect their shared Semitic origins.

Over the past two hundred years, there has been a major cultural divergence. As part of the Jewish Enlightenment, many European Jews embraced secularism and scientific progress. This shift may have been facilitated by the community’s historically high levels of education (due to religious emphasis on Torah study) and their experiences as a minority group specialising in commerce and skilled trades.

In 20th Century USA, Jewish reformists played pioneering roles in struggles for social justice, secularism, and feminism.

But there is always contestation, some sects are Ultra-Orthodox. In Israel today, the Haredi community offers a striking example of how economic growth isn’t enough to dislodge religious conservatism. Only 56% of Haredi men are in the workforce, as many dedicate themselves to studying the Torah. This lifestyle is often supported by a combination of government welfare and their wives’ salaries.

Jewish history is thus a perfect example of reform and backlash.

Modern Threats and Religious Backlash in the Middle East

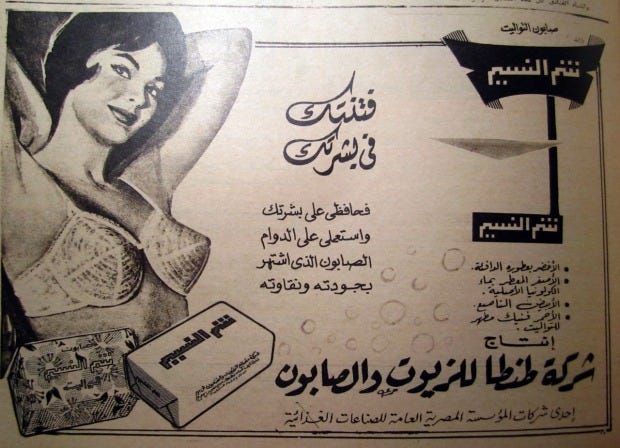

In the early 20th century, traditional religious authorities faced a crisis of legitimacy, having failed to protect Muslim lands from European imperialism. This vacuum was initially filled by Arab modernisers who championed secular, socialist visions of progress. Leaders like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser encouraged women to enter the public sphere and embraced Western-style modernisation. In 1950s Cairo, advertisements even featured women in bikinis.

This modernisation project stumbled. Economic stagnation and military defeats, particularly against Israel in 1967, discredited secular nationalism. As women gained more public presence through education and employment, it also triggered a conservative backlash.

Religious entrepreneurs seized this moment, framing the failures of modernisation as divine punishment for abandoning Islamic principles. Using new technologies – radio, cassettes, and later, satellite TV – they promoted a return to ‘authentic’ Islamic values. For example, in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood utilised cassette tapes to spread their message in the 1970s and 1980s. These tapes, easily copied and shared, allowed conservative interpretations of Islam to reach a wide audience.

This Islamic revival wasn’t just a grassroots movement. Struggling rulers, seeking legitimacy, increasingly cloaked themselves in piety and institutionalised religious instruction. Saudi Arabia, flush with oil wealth from the 1970s oil crisis, funded the spread of its conservative Wahhabi ideology across the Muslim world. They established madrasas (religious schools) and mosques, and funded Islamic charities, all of which promoted a more conservative interpretation of Islam.

The result was a profound cultural shift. Gender segregation, once seen as ‘backward’ by modernisers, was reframed as a moral imperative. Veiling, which had declined in many urban areas, saw a resurgence. In Egypt, for instance, the percentage of women wearing hijab increased dramatically from the 1970s to the 1990s.

The key lesson from the Middle East and North Africa is that culture is not set in stone, there is always scope for persuasion. That said, the odds of successful liberalisation were always low. In 1960, female labor force participation rates were strikingly low across the Arabian peninsula, averaging about 6%. In MENA, the average was only slightly higher at 22%.

Male honour was deeply contingent on female seclusion.

Islamisation in Indonesia and Malaysia

Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim-majority country, provides a striking example of how improved communications and prestige bias can reshape cultural norms, especially in the context of newfound religious freedom.

Under Suharto’s authoritarian regime (1967-1998), Islam had been heavily repressed, with hijabs banned in schools. The fall of Suharto and subsequent democratisation opened up space for religious expression and organisation. This newfound freedom, coupled with improved communication technologies, enabled Indonesian Muslims to more easily undertake the hajj pilgrimage and study in prestigious centres of Islamic learning: Cairo and Saudi Arabia.

20% of Indonesian school children now study in religious schools. Salafist preachers, meanwhile, leverage social media and online platforms to spread their message. YouTube channels featuring Arab-trained imams have gained massive followings. Activists have also successfully mobilised for state schools to include more religious instruction, and for Sharia-inspired laws.

Politicians now gain legitimacy by institutionalising religious prohibitions and punishments for perceived blasphemy. In 2022, the Indonesian parliament voted unanimously to expand punishments for blasphemy, with offenders facing up to five years imprisonment. In Aceh, women are forbidden from visiting restaurants after 9PM without a male guardian. By 2024, at least 30 local regulations restricted activities by religious minorities, and 120 local regulations mandated the hijab.

But the struggle to define Southeast Islam is a constant tussle. Liberals are pushing back against what they see as ‘Arab colonialism’. Malaysian sociologist Syed Farid Alatas warns,

‘What we are importing is not the faith but the practices and beliefs from a culture from Saudi Arabia... This narrow interpretation of Islam can undermine the diversity of our religion’.

Central Asia's Religious Revival

After decades of Soviet-enforced atheism, Uzbeks are increasingly embracing Islam. This religious resurgence defied liberal expectations. The advent of greater freedoms has not led to secularisation, but rather to a religious revival.

As religious persecution rescinds, Central Asians are increasingly heading to mosques, subscribing to YouTube imams, learning Arabic, and hosting sex-segregated ‘Islamic weddings’. Young Uzbeks express reverence for Arab and Arab-trained imams, viewing them as having a ‘pure Islamic education’.

This trend is facilitated by online platforms. One of the most popular online imams, Abror Muxtor Aliy, has three-quarters of a million followers on YouTube and says that wives should obey their husbands.

The ability to freely practice and learn about their religion has allowed Central Asians to reconnect with their Islamic heritage, often gravitating towards conservatism. When I asked which country they’d most like to visit, many older Uzbeks said Saudi Arabia, reflecting its historical prestige.

As with Indonesia, this revival has a self-reinforcing aspect. As more people visibly embrace Islamic practices, it signals wider religosity. This can encourage others to openly express their faith, creating a cascade effect of religious observance. Marriage markets are a key mechanism: men often want hijabi brides.

Global Islamic Media: Al Jazeera and Islam Channel UK

The influence of Arab Islamic thought extends far beyond the Middle East and Central Asia, reaching global audiences through media networks like Al Jazeera and Islam Channel in the UK.

Al-Jazeera, broadcasting in over 150 countries and reaching a global audience of 430 million people, has played a significant role in promoting conservative Islamic views, particularly on gender issues. While the network champions open debate on many topics, it takes a much more conservative stance on gender.

In the UK, Islam Channel reaches an estimated 60% of British Muslims. Its religious programming often features scholars trained at Al-Azhar University in Egypt, answering questions about everyday life in Britain. Al-Azhar trained scholars answer questions like: ‘Is it permissible for divorced parents to talk together in an enclosed space?’ (No), or ‘Can a lady wear perfume in public?’ (No, as it will attract undue attention). This direct line from callers in Birmingham to scholarship in Cairo attests to the power of prestige bias.

“Forbidding Wrong” on TikTok

The rise of social media platforms like TikTok has created new arenas for large-scale shaming, particularly around religion and gender. Young influencers often use the platform to enforce strict interpretations of Islamic modesty.

Digital enforcers shame women for wearing belts with abayas (deemed too revealing) and label men as ‘dayooth’ (lacking protective jealousy) if they allow their wives to be seen in public or post family photos online.

Islamic feminists are pushing back, satirising excessive policing. Charismatic young comedians mock the idea that they need to sleep in their hijabs ‘just in case’. The struggle to define Islamic orthodoxy is now a digital tug-of-war.

The Struggle of Islamic Feminists

In this context of conservative revival and digital moral policing, Islamic feminists face significant challenges. Their efforts to promote gender equality within an Islamic framework often meet with fierce resistance, much of it rooted in Arab prestige bias.

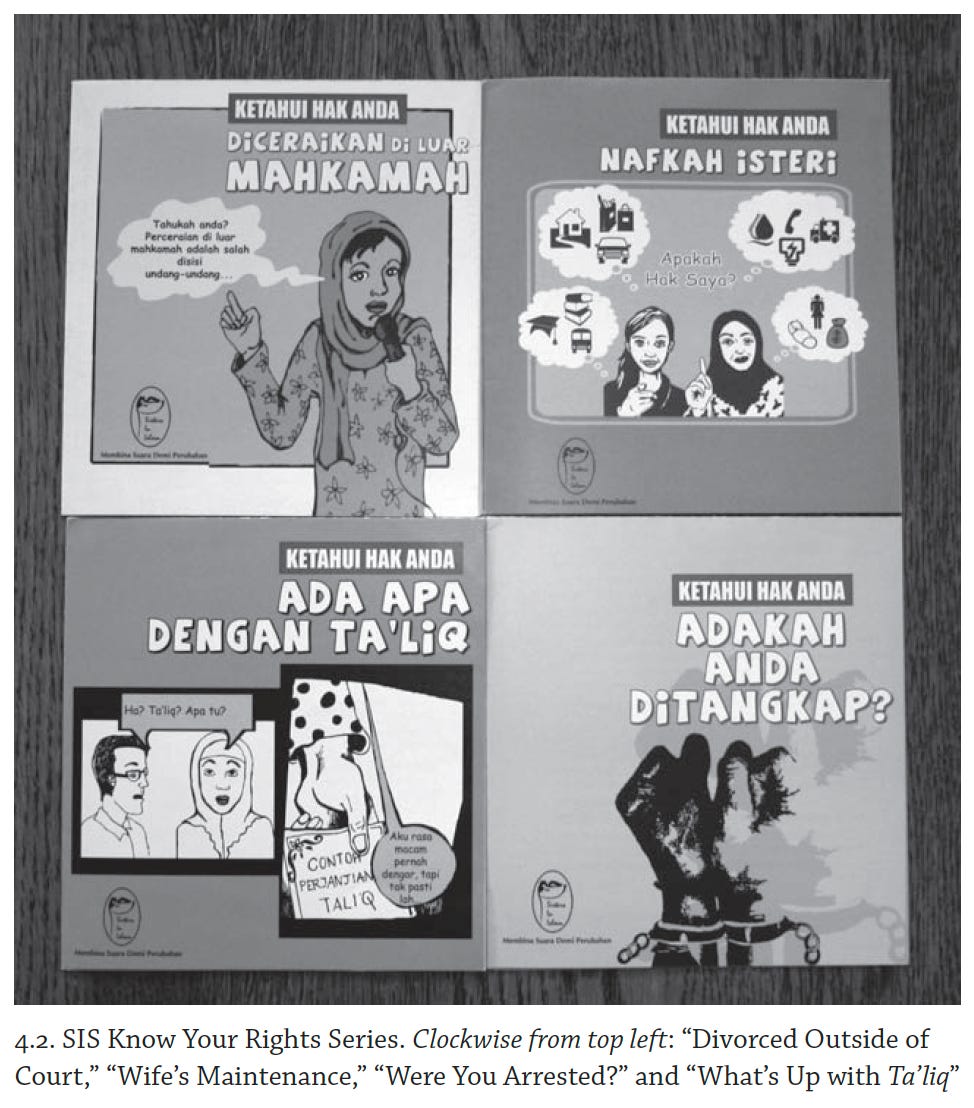

In Malaysia, for example, the organisation ‘Sisters in Islam’ has faced intense backlash. Their campaigns for gender justice are often dismissed as ‘anti-Islamic’ and ‘ignorant’ because they lack the perceived legitimacy.

A conversation recounted in Azza Basarudin’s book “Humanizing the Sacred” illustrates this challenge:

Religious Leader: "SIS is dangerous because it has poisonous knowledge. SIS members are not necessarily trying to present the real Islam. They talk about women’s rights like Westerners and converts who do not understand Islam…

SIS members do not have Islamic education but claim to be experts. Religious matters are very complicated, and this is why we have ulamak who have conducted in-depth study of Islam and are experts. These women should leave Islam to the ulamak."

Researcher: "What do you consider suitable religious education?"

Religious Leader: "Having a well-rounded knowledge of Qur'anic sciences, Islamic history and law, as well as having studied with credible ulamak in madrasah in places like Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Can SIS members read, write, or speak Arabic? Can they read the Qur'an in its original language?"

Similar challenges are faced by Muslim feminists in academia. Professor Asma Barlas, author of ““Believing Women in Islam”, faced heckling and accusations of lacking scholarly authority when presenting her research on equal spousal rights in the Quran at a London university. Her lack of formal training from a prestigious Islamic institution undermined her credibility.

Arab prestige bias thus creates significant barriers for Islamic feminists and liberals seeking to reinterpret religious texts as more egalitarian.

The lesson from the Muslim world is that neither economic development, democratisation nor technological advances necessarily promote gender equality. That said, political freedoms are certainly a pre-condition for feminist contestation - as demonstrated by China.

China’s Totalitarian Paradox

Totalitarian states can direct massive social engineering, but that change is ultimately contingent on top-down directives. The Communist Party initially implemented top-down initiatives to promote gender equality, including radio propaganda and the ‘Sent-Down Youth’ movement, which did encourage gender equality, but subsequently faded.

Under authoritarian rule, Chinese feminists are silenced and sabotaged. Prominent activists, like the ‘Feminist Five’, have faced arrest and detention for planning anti-sexual harassment campaigns. Online feminist content is often quickly deleted, while accounts of outspoken feminists are regularly suspended.

Refusing to take this lying down, Chinese women have found creative ways to resist and cultivate solidarity. Platforms like ‘Little Red Book’ (Xiaohongshu) have become spaces for women to share experiences of discrimination and support each other - under the hashtag ‘Girls help girls’. Despite censorship, Chinese women have shared stories of sexual harassment and assault, particularly in universities and workplaces. And in practice, many women are simply refusing to marry or bear children.

However, without the ability to organise freely or influence policy directly, this activism struggles to translate into systemic change. Despite younger women’s growing support for gender equality, institutions remain extremely patriarchal. Employment discrimination and male violence persist with impunity. Meanwhile, the manosphere teams with misogyny.

China shows us that there is no unconditional historical persistence. Sorry to brag, but I actually I learnt that over ten years ago, during my PhD fieldwork in Zambia.

Zambia: Debunking ‘Cultural Persistence’.

The Zambian Copperbelt offers compelling proof of rapid cultural change. From the 1930s to 1980s, the region’s rich copper deposits were mined, managed, and administered almost exclusively by men. Economics reinforced patriarchy, with women largely stereotyped as housewives and men presenting themselves as masters of their households. Public leadership was male-dominated.

However, economic insecurity - caused by the falling price of copper, neoliberal reforms, and HIV/AIDs - catalysed significant rupture. As men became less able to provide for their families single-handedly, many forfeited social respect in exchange for the economic advantages of female labor-force participation.

Over time, prolonged exposure to women demonstrating their equal abilities in socially valued domains gradually eroded gender stereotypes. This change has been particularly noticeable in cities - which are often catalysts of social change.

Latin America: From Machismo to Feminist Revolution

Over the past few decades, Latin America has become a hotbed of feminist activism and cultural transformation, offering a fascinating case study in how deeply entrenched conservative norms can be upended.

Rewind to the mid-20th century, and you’d find a region steeped in machismo and conservatism. Legislation sometimes curtailed women’s freedom to work outside the home, open bank accounts, or even appear in court. Divorce was often illegal, and the Catholic Church reigned supreme. Authoritarian regimes, from Chile to Argentina, often shored up their power by courting religious conservatives, further entrenching patriarchy.

But beneath the surface, tectonic shifts were occurring. As urbanisation accelerated and economic pressures mounted, more women entered the workforce. Unlike the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, Latin Americans never idealised female seclusion. This meant that when economic opportunities arose - or crises hit - women could step into public roles without being scorned or stigmatised.

The 1970s and ‘80s saw a wave of democratisation sweep across the continent, often with women at the forefront. In Argentina, Madres de Plaza de Mayo became iconic figures, challenging their children’s ‘disappearances’ under the military dictatorship. Their activism not only contributed to the fall of the regime but also set a precedent for women’s public political engagement.

As democracy took root, a culture of resistance blossomed. Citizens, having toppled dictators, realised they could effect change through collective action. This spirit of activism provided fertile ground for feminist activism. Regional networks brought together women to share strategies, inspire each other, and build solidarity.

Meanwhile, popular culture was undergoing its own revolution. Television, that great influencer, began featuring feisty independent female protagonists. Brazilian telenovelas, watched by millions, started portraying women leaving unhappy marriages and thriving independently. Research by economists Chong and La Ferrara even found that these shows led to real-world increases in divorce rates!

US media, amplified by cable TV and later streaming services, further encouraged cultural liberalisation and secularism. When I visited a women’s book club in Puebla, Mexico, the members were excitedly discussing their favorite show on Netflix - “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel”, which portrays a young woman becoming a stand-up comic.

This cultural shift expanded the space for contestation. Feminist activists successfully campaigned for gender quotas, leading to a surge in women’s political representation. Domestic workers - triply disadvantaged by race, class and gender - secured new-found protections. Relentless activism has also led to the legalisation of abortion - a seismic shift in a region once dominated by conservative Catholics.

No longer silenced by shame, women have collectively mobilised against ‘machista violence’. The “Ni Una Menos” (Not One Less) movement, which began in Argentina in response to femicides, has spread across the continent, bringing hundreds of thousands of women into the streets.

Latin America has become much more gender equal, thanks to growing embrace of liberal freedoms, human rights, democratisation, secularism, ideals of romantic love, US prestige bias, and relentless feminist activism.

Pushing Boundaries

For all this talk of contestation, we must also recognise that it does not occur in a vacuum. Each society has unique conditions that shape the scope of what’s considered permissible. Push too far, outstrip public opinion and conservatives will organise resistance.

Economics and culture shape the ideological boundaries:

Skill-biased technological change and rural-urban urbanisation can weaken kinship dependencies, expand social networks, foster individualism, and increase the returns to female employment.

The rise of skilled, psychologically rewarding, and high-paying jobs also makes careers much more attractive to women.

Sustained growth may also increase government’s ideological legitimacy. Failure to deliver, meanwhile, can weaken secularists’ credibility.

Cultural and religious values - such as female seclusion, romantic love, collective harmony, secularism, as well as beliefs about upward mobility - all play crucial roles in shaping public receptiveness.

If progressive reforms far outstrip median attitudes, this can trigger backlash.

The Never-Ending Fistfight

Cultural fistfights continue, with no final round in sight. From the television studios of 1970s America to the TikTok feeds of modern Muslim youth, from the mosques of post-Soviet Central Asia to the academic halls of Western universities, culture remains an eternal battleground.

Different factions vie for influence, trying to persuade others and entrench their views in institutions – be it schools, laws, or social media algorithms. It’s a never-ending process of renegotiation.

Our global tour of cultural contestation reveals several key insights:

Culture is never static. It’s constantly negotiated and renegotiated, with progressive and conservative forces in perpetual tension.

Economic growth, technological advances and political freedoms do not entail cultural liberalisation. These are merely vehicles - to be used by progressives and conservatives alike.

Each society has a distinct space; push too far and there will be backlash.

So the next time someone tells you ‘it's tradition’, remember: culture isn’t a fossil, it’s a fistfight. And it’s happening all around us, all the time.

The only question is: how to win?

So insightful!

Reading this, and some of your other work on culture, religion, and the specific issue of women in the workforce is whether religions that have a history of "professional" women in religious roles might create cultures that are more welcoming of women working outside the home than those that do not have such a history.

For instance, I note that Christianity, Judaism, and Islam share a similar history, some texts, and many articles of faith. One difference, however, is that Christian churches have a history of women's religious orders (e.g., nuns) that go back to the very founding of the religion. Nuns are career women--sure, unmarried and in the church, and subordinate to priests, but women who have a full-time career outside the home that is appreciated as being valuable nonetheless. Buddhism, similarly, has career women/nuns working for the faith. While they're not adult full-time careers the way being a nun is, Shintoism has paid priestesses. So, while very different religions, Christianity, Buddhism, and Shintoism all have a space for women to work outside the home for the religion.

On the other hand, women as rabbis did not exist until fairly recently, and only among a minority of Jewish congregations now. To this day, Islam does not have women in career religious positions.

So I wonder if this deep history of women working outside the home (albeit, for the church) had a long-term effect of making cultures more friendly toward the idea of women working outside the home in general.