China's Economic Slowdown & Social Media

“A man has to be successful. If you’re not successful, you won’t get married. Male high school teachers have low social status. It’s hard to find a relationship. But if you don't get a wife, you don't get kids. Then for your ancestors, your whole generation just ends. This means a lot to Chinese parents.

Men think it’s easier for women to have a better life. They can easily find a guy with a higher social status. But for men like me, we have to be very successful” - explained Chen.

This is a crucial insight.

If we just look at labour market data or listen to women’s experiences, we see rampant sexism. But that blinds us to a parallel phenomenon: male resentment.

Given China’s uneven sex ratios, brides are in heightened demand and can easily marry up. Even though employers discriminate, men may still think that women have it ‘easier’. Economic slowdown has compounded frustrations, which are reinforced on male-dominated sites like ‘Baidu Tieba’.

Let me elaborate.

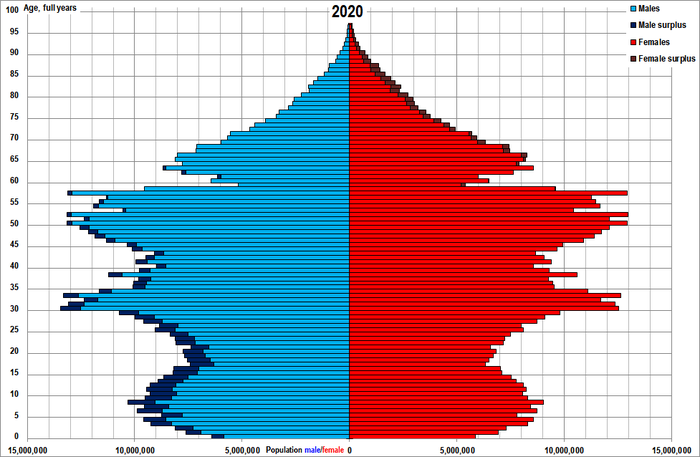

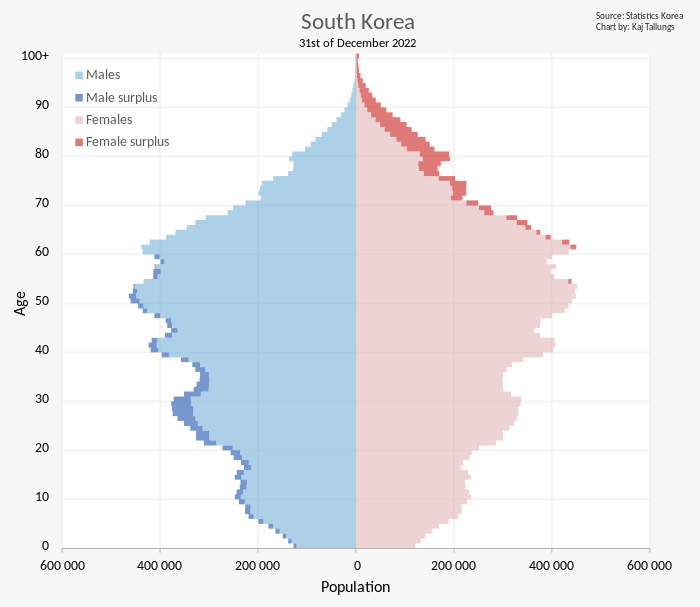

Male-biased sex ratios

East Asia was traditionally patrilineal. Sons were celebrated as scions of the family line, performers of ancestral rituals, and providers of old age security. Boys were strongly preferred - cue male-biased sex ratios.

Fertility has also fallen. Unlike India, Chinese and Korean men cannot simply find a wife by going younger, because that pool is even smaller.

Competition for brides is tough, especially for men without wealth.

Bias? What Bias?

Growing up, boys may not necessarily see female disadvantage.

School girls and boys wear the same uniform, compete on merit, and have comparable family wealth. This sustains perceptions of parity.

Even if women are disadvantaged at work and bear the lion’s share of care work, this is not necessarily seen as unfair. Remember, before the '1970s, US books and newspapers never mentioned ‘sex discrimination’.

Similarly so for China, many men tell me they did not perceive anti-female bias.

Economic Slowdown Fosters Resentment

“Because of the economy, everyone is stressed, angry and angry. But you can’t protest because the government is repressive, so you vent and blame others, who are weaker” - continued Cheng.

China’s economy has slowed, while unemployment has soared. Finding a good job has become extremely hard. Competition has intensified.

Tough times tend to change our psychologies, spawning hostility and resentment. If social mobility is thwarted, people tend to believe the world is ‘zero sum’: your success is my loss.

(See my post on this new paper by Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira and Stefanie Stantcheva)

As Cheng observed, stalled progress breeds antagonism.

(Segue: the Bemba in Zambia have a great word for this: ‘icifukushi’. The ‘c’ is pronounced ‘ch’. It’s often used to describe the pent-up frustrations of unemployed men.

Filter Bubbles Collectively Direct Resentment

Zero sum mentalities do not have an inevitable manifestation, they are equally common on the political left and right. Likewise in China, resentment needn’t be targeted at women. Conceivable, one might blame authoritarianism, corruption, economic policy, or labour-displacing automation.

Charismatic cultural entrepreneurs and filter bubbles construct the legitimate targets for animosity, shaming and vilification.

Chinese social media is somewhat sex-segregated. Baidu Tieba is mostly male, while Little Red Book skews female. Both apps allow users to post and comment. Separately, they manufacture diverse perceptions.

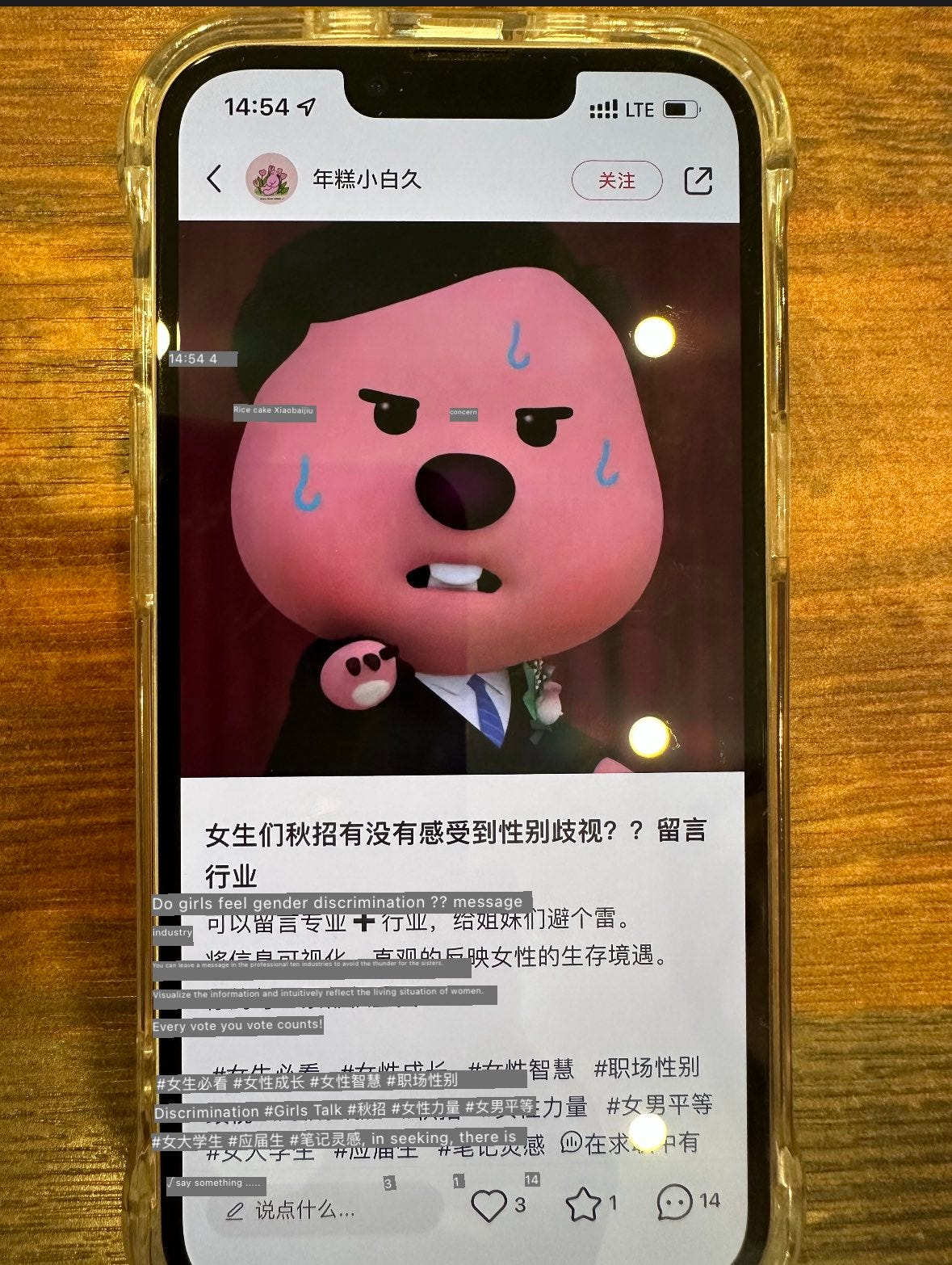

Little Red Book

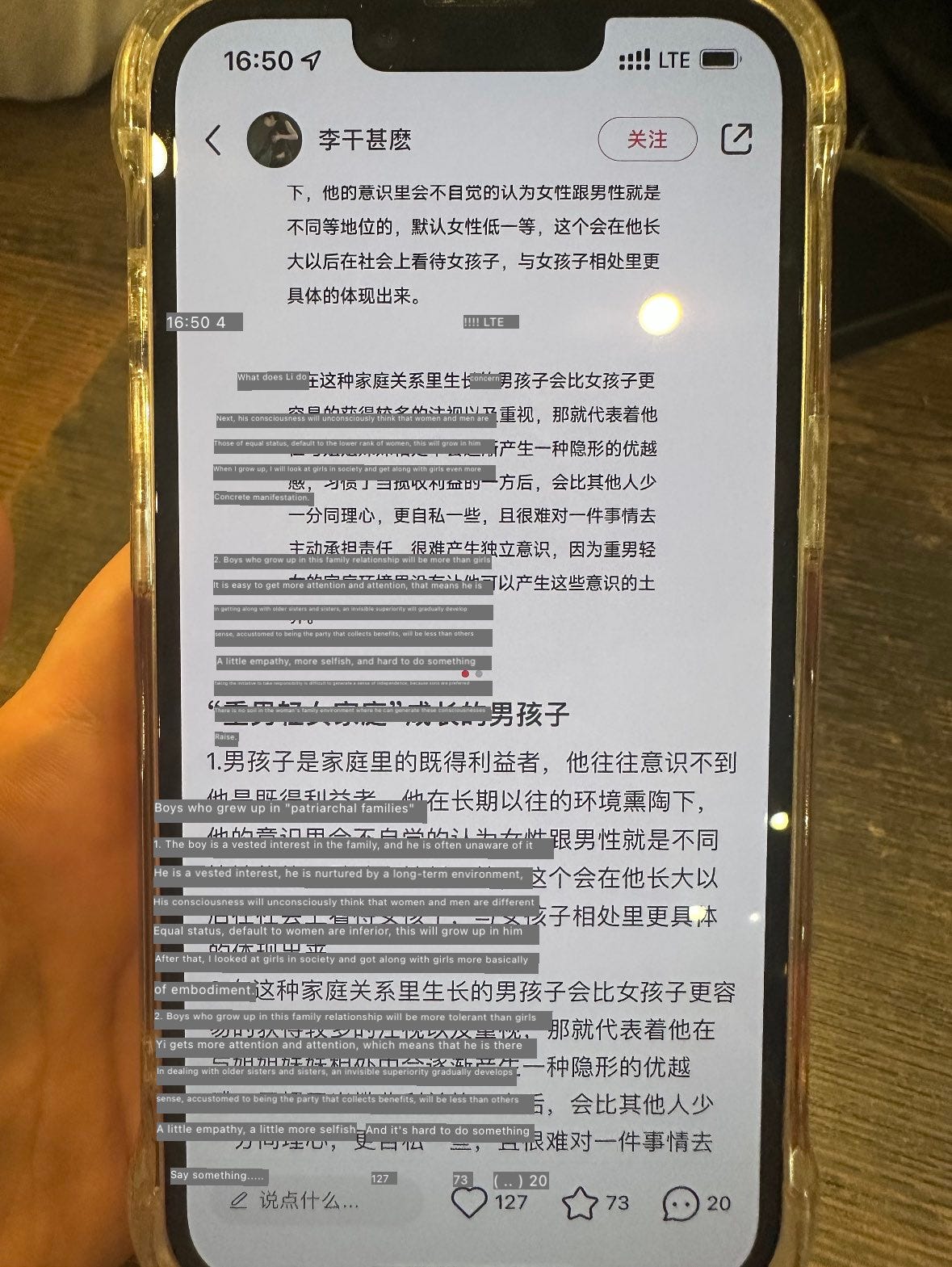

On Little Red Book, women often share stories of sexism. Below, for example, one user laments that sons are lavished with praise, then feel entitled to deference.

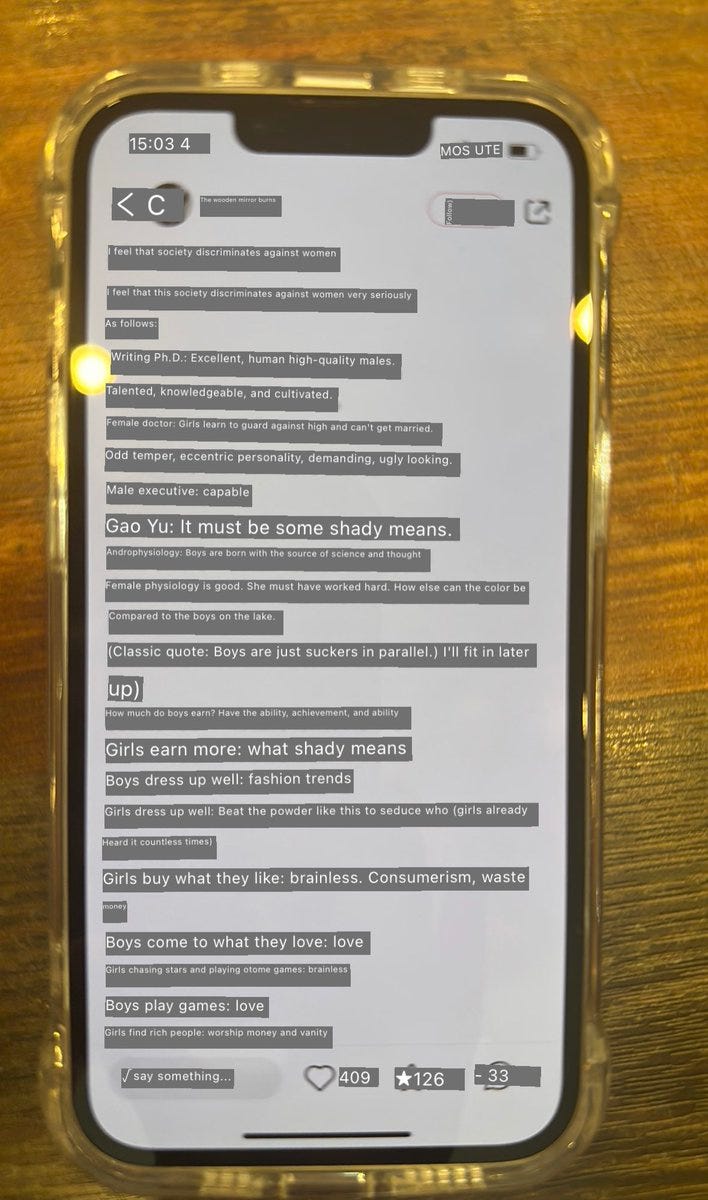

On “Little Red Book”, women cheer for Yang Li (a stand-up comic), who gave rise to the popular meme:

“How can men be so average, yet so full of confidence?”

Men were enraged, while many women concurred.

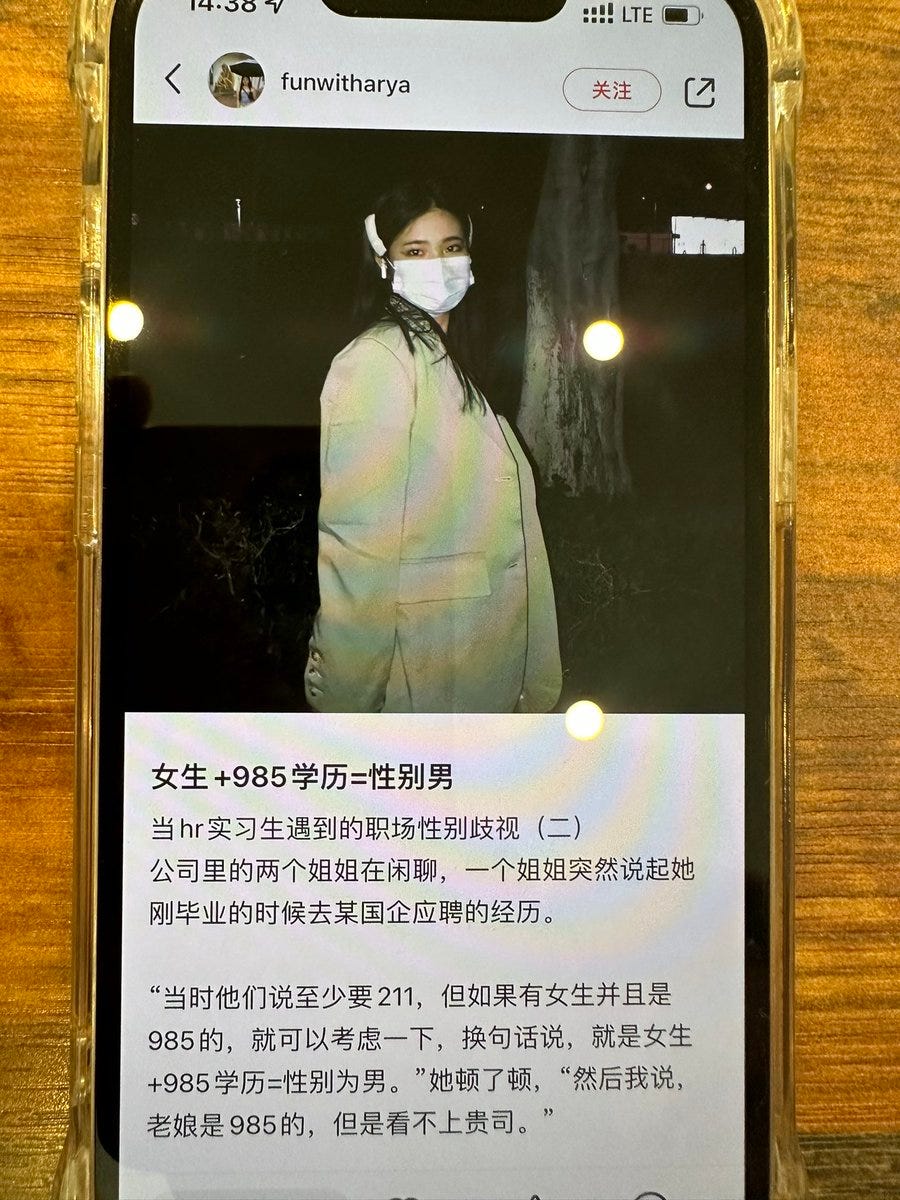

This woman says “A woman + 985 = male”.

985 means a prestigious university.

So an exceptionally clever and qualified female is equal to a mediocre male.

Another user invites women to share their experiences of employment discrimination. One replies that she went to a recruitment fair where they openly told women, “don’t bother applying” (i.e. we want men).

If a guy has a PhD, then he must be very talented. But if a woman has a PhD, then she is perceived is over-educated and unwilling to marry - another bemoans.

Collectively, Chinese women are highlighting unfairness in families and companies. Rather than blaming themselves, many realise the game is rigged. Media horror stories (like the woman who was chained and used as a baby-making machine) catalyse discussions among friends. By identifying systematic bias, Chinese women are constructing and legitimising feminist consciousness.

But that’s where it ends.

Authoritarianism inhibits activism. Adversarial women have been imprisoned. Seldom seeing successful dissent, many remain despondent. Absent independent organisations, women have little option but to navigate around bigotry.

Baidu Tieba

Manospheres brim with misogyny. Men tell each other tales of selfish, stupid, incompetent, greedy, grasping, ugly, nasty, whoreish women. Mockery and insults run rampant. Users who are utterly disgusted opt out, leaving the group to joke with impunity.

Baidu Tieba is no exception.

As one vlogger complained, it’s a “feast of humiliating women”

If a group is culturally homogenous and members applaud each other, they may see popular discourses as perfectly legitimate.

“I used to be like one of those guys on the app. I sent the jokes to my girlfriend - calling fat girls names of tanks, and about bride price”.

“She said, ‘I’m uncomfortable with what you’re saying’. A girl was dating with many men, I called her a bitch, my girlfriend was very angry. I was unaware, there are very serious serious” - Cheng.

By sharing a feminist perspective, Jing helped Cheng become much more empathetic.

Friendships are the foundation of feminist consciousness. Trusted friends can help others understand gender inequalities - as I learnt in Catalonia and the Zambian Copperbelt. People are much more receptive to ideas from someone they trust and respect.

Is China becoming More Gender Equal?

In this post, I’ve tried to show two sides of socio-economic change in China.

On the one hand, rising wealth, education, urbanisation and internet access have generated platforms for feminist consciousness. Apps like Little Red Book enable millions of women to share their stories, publicly affirm their righteous indignation, cheer for each other, and lambast sexism. With a little help from their friends, men like Cheng come to embrace equality.

Cultural change is clearly possible, but it’s thwarted by political repression and economic slowdown. Moreover, objective data on labour market inequalities blinds us to the enormous pressures on men.

Although Chinese women face major obstacles in employment, men may still see them as having ‘an easier life’.

Adverse sex ratios and tough marriage markets augment the importance of men’s economic success, while soaring unemployment simultaneously makes this untenable. Despite huge parental investments, many men are set up to fail.

Criticising the government is downright dangerous. A rising tide of resentment cannot be channeled against authoritarianism. Instead, filter bubbles like Baidu Tieba rally for misogyny.