The Emergence of Chinese Feminist Consciousness

“Girls help girls”

The Chinese state is ultra authoritarian. Big brother is always watching; dissent is sternly punished. Totalitarian surveillance is also run by men. The Politburo is entirely male, the Central Committee remains 94% male. When five feminist activists put up stickers against sexual harassment, they were imprisoned. Repression saps resistance, reinforces despondency, and enables impunity for abuses. Police ignore male violence, law courts keep wives trapped, and employers continue to discriminate.

So is Chinese feminism suffocated?

No!

While criticism of the CCP risks incarceration, disapproval of other people is generally tolerated - so long as there is no organised dissent, viral outcry or social instability. Chronic insecurity and intense competition boil over - not upwards but sideways - in cross-class antagonism.

The same applies for gender. By interviewing Chinese young men and women, discussing social media, I have learnt that even through censorship deters bottom-up mass mobilisation, there is a strong and emerging feminist consciousness. On “Little Red Book” (Chines Instagram) women are outspoken. They condemn sexism, son preference, sexual harassment, maltreatment, male violence, and labour market bias.

“Girls help girls” has become a popular hashtag. It encapsulates lateral solidarity.

This Substack explores:

How women’s economic independence and the demise of patrilocality have nurtured a shift in female psychologies

The emergence of female solidarity

How feminist consciousness sheds light on the persistence of authoritarianism.

Women’s economic independence and the demise of patrilocality

“It’s important to make our parents proud” - reiterated Mei Lien and Jieyi from Guangzhou, as we chatted over a long lunch of Malatang.

“How do you do that?” - I asked.

“By going to a good college.. and getting a good job”

“What about getting a good husband?”

“Yes, but that’s not so important. My parents want me to be economically independent”

“A husband will respect and treat a woman better if she’s economically independent”.

Filial piety remains paramount. Parents are respected and owed loyalty for bringing their children into the world and making sacrifices. Social connections (‘guanxi’) are equally cardinal. Mei Lien’s uncle has secured her internships and job placements. These traditional institutions persist. But female worth is no longer reduced to chastity, marriage and male heirs.

60% of Mei Lein and Jieyi’s age mates are enrolled in higher education, pursuing careers. Over 60% of Chinese women are in the labour force, seeking marital equality. Gone are the days of patriarchal dependency. Chinese women now strive for economic independence.

Mei Lien and Jieyi were always encouraged to pursue their own advancement. Departing from Confucianism, neither parents ever said they should obey their husbands. Echoing a wider trend, Jieyi’s parents are happy with their two daughters. At school, boys and girls were treated equally. And just like men, women increasingly socialise with friends, travel for university, work in large companies, live outside the family, choose their own boyfriends, and marry in their late twenties.

Collectivist loyalties persist - but these now run vertically to parents, not diagonally to in-laws.

Families are increasingly nuclear. Only a minority of Chinese people want to live with parents or in-laws. Divorces are on the rise. Society in general has become much more individualistic. No longer rooted in patrilocality, Chinese young women are becoming more like their male peers.

So, while middle-class daughters are still loyal to their parents, they are no longer schooled to submit to their in-laws.

This sharply contrasts with much of South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa - where girls’ safety is secured through paternalistic restrictions, while social networks rely on socialising girls to endure abuse and please their in-laws.

The emergence of female solidarity

China is still incredibly patriarchal. The difference today is that young women are no longer reliant upon (nor restricted by) patriarchal guardians. Most 20-somethings are single, self-reliant, careerists - out navigating the world. Like US women in the 1960s, China’s Gen-Z are trying to make it in a man’s world. This affects how they address sexist discrimination.

Paradoxically, son preference and uneven sex ratios may have aided female solidarity. Given surplus males, lower-ranked men struggle to date and marry. Women by contrast have plenty of options. This may have reduced female competition and antagonism. Whereas in Mexico, young women often expressed distrust and eyed other women with suspicion - out to steal their men.

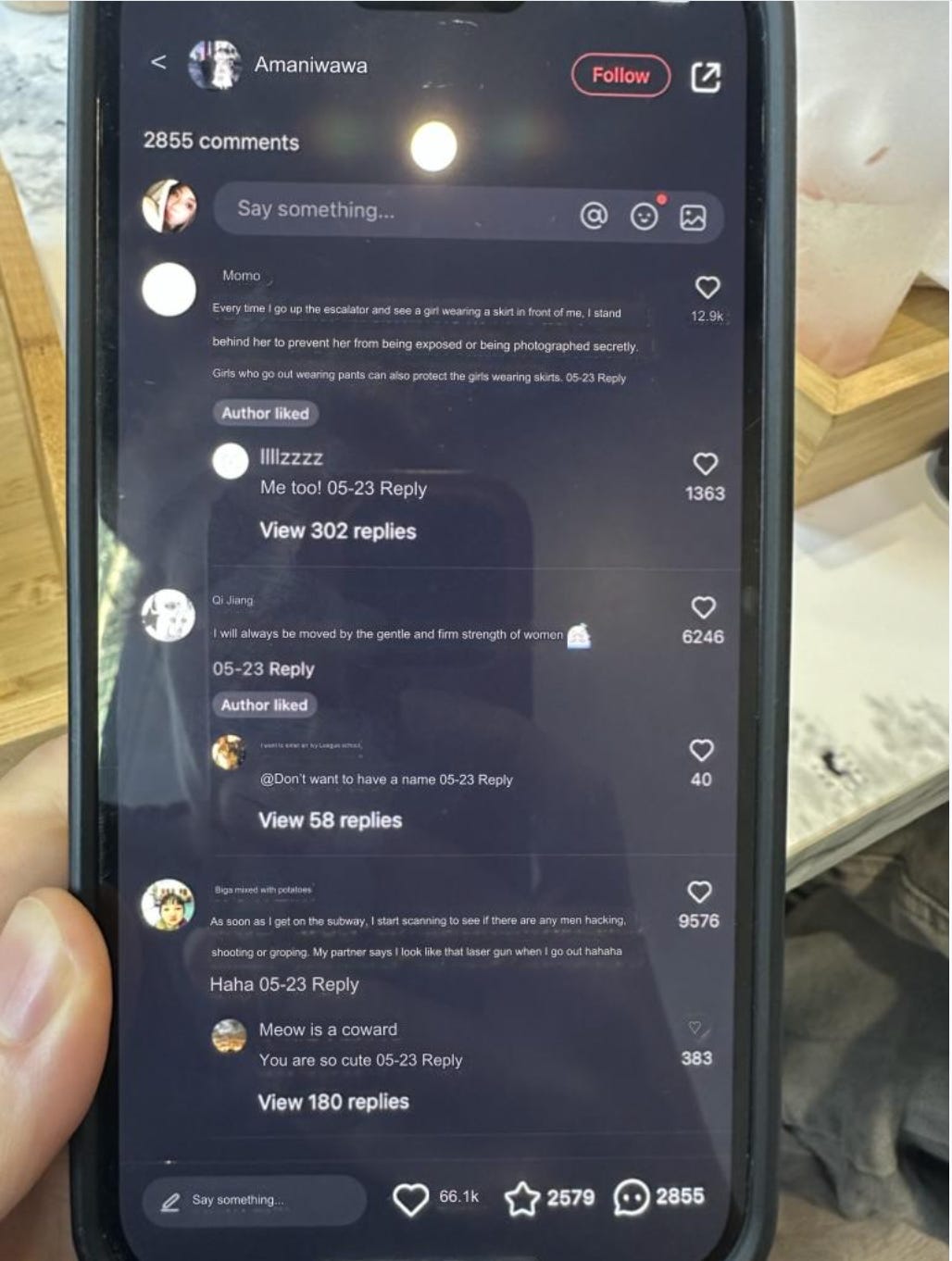

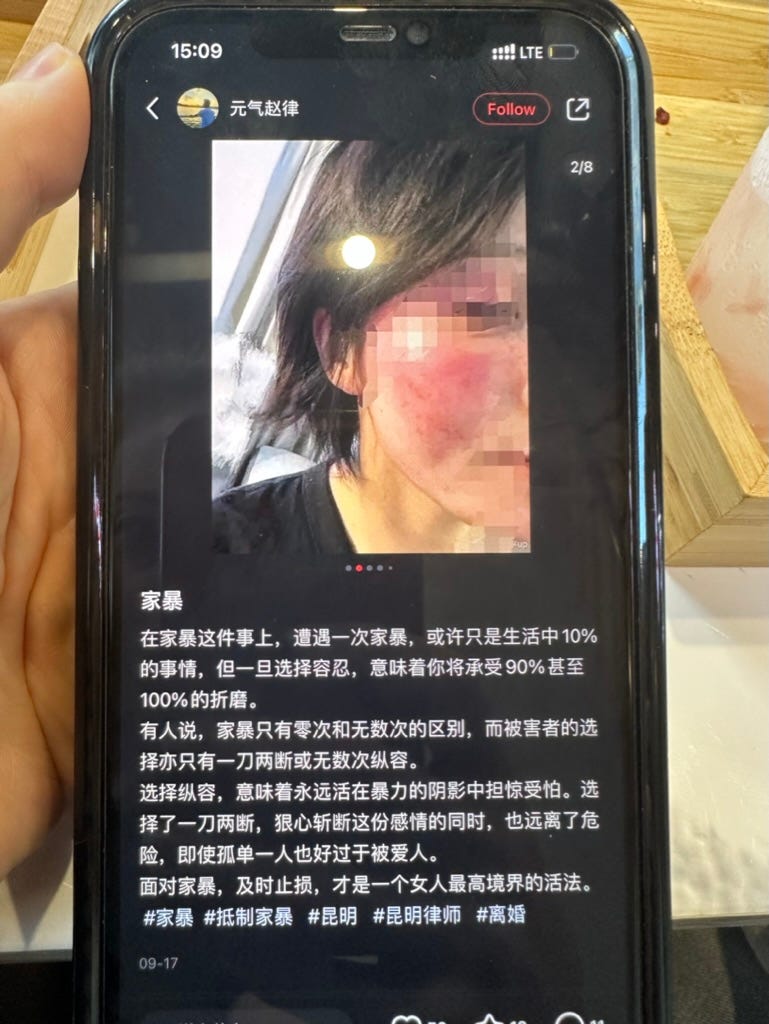

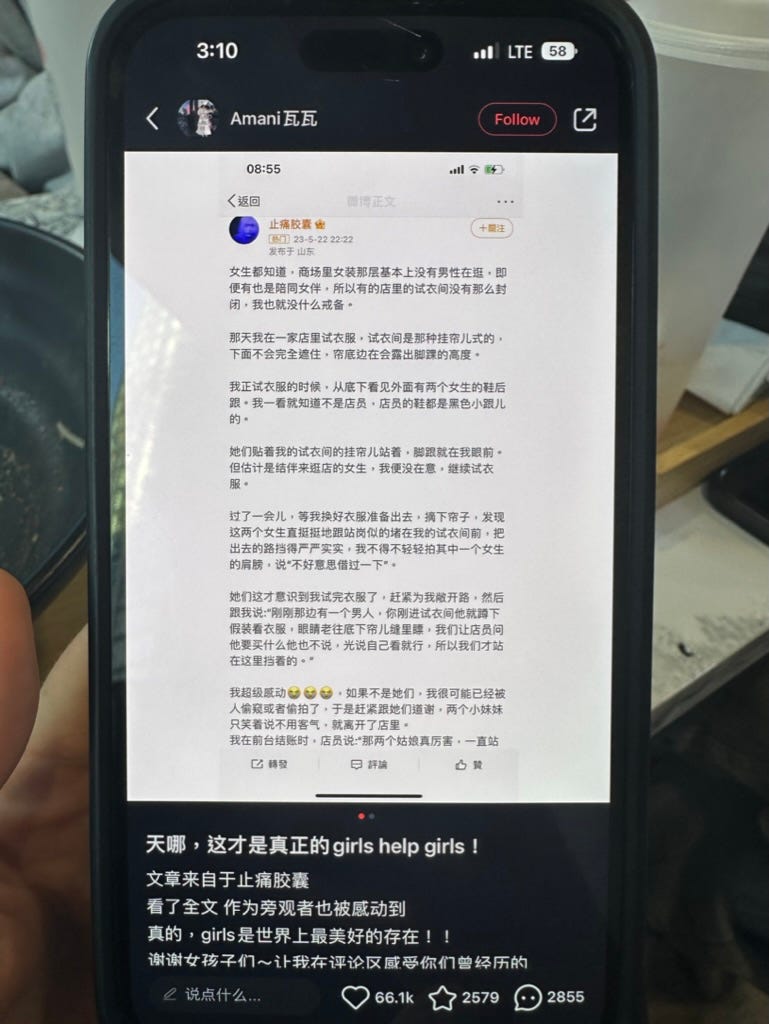

“Girls help girls” has become a popular hashtag of female solidarity. Women bemoan patriarchal privileges, condemn domestic violence, encourage other women to escape abuse, share stories about female solidarity, and offer advice.

Since “Little Red Book” is primarily popular with women, it is something of a filter bubble. There is very little patriarchal pushback. In this online room of their own, Chinese women decry sexism and reinforce righteous resistance.

Mei Lein and Jieyi kindly showed me posts about “girls help girls”. It’s all about Chinese women helping and supporting other women. Despite the suppression of feminist mobilisation, China is seeing emerging feminist consciousness.

Feminist consciousness sheds light on the persistence of authoritarianism

There are perhaps two major theories of why China is so totalitarian: culture versus institutions.

In “The Rise and Fall of the East”, Yasheng Huang argues that the keju imperial examinations incentivised widespread rote learning of ancient Confucian texts. This suppressed scientific innovations and political dissent. Habituated to rule-following, Chinese people lack a culture of resistance.

“Outsourcing Repression” takes a different tack. Rather than emphasise culture, Lynette Ong focuses on the CCP’s contemporary strategies. The CCP outsources repression to thugs and harnesses social networks for ideological persuasion. This includes groups with loudspeakers standing outside your house shaming you for defying development and selfishly refusing to move. These twin strategies enable the CCP to force massive evictions, without triggering unrest.

To me, the rise of feminist consciousness shows that Confucianism is being criticised. Women are rejecting sexist traditions, decrying myriad abuses, and forging solidarity. Repression means this is expressed sideways rather than upwards.

My gratitude to Chinese male and female migrants in Toronto who have vastly improved my understanding.

Critique and comments are always welcome.