Prestige Bias

Kim Kardashian, Elon Musk, Daron Acemoglu, and al-Azhar; what do they all have in common? Prestige.

Elon Musk’s tweet causes a cryptocurrency frenzy. Kim Kardashian’s outfit becomes an overnight fashion sensation. Daron Acemoglu and colleagues’ paper on settler mortality reshapes economic thinking. The Pope’s words influence millions globally. What links these diverse events? They’re all powerful manifestations of prestige bias.

Psychologically, we seek guidance from those who’ve achieved success, looking to emulate their paths to prosperity and social approval. This creates a dynamic where the accomplished influence others, often reinforcing their own status in the process.

From NBER’s Summer Institute to the glitz of Hollywood, prestige bias permeates every sphere of human endeavour. However, its impact is perhaps most profound and far-reaching in the realm of religion.

Join me on a journey to the heart of the Muslim world, where we’ll explore the influence of Cairo’s Al-Azhar - a beacon of Islamic scholarship whose teachings reverberate globally. Through this lens, we’ll uncover how prestige bias shapes not just individual choices, but entire cultural paradigms.

Daron Acemoglu and Institutions

In 2001, Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson published a paper in the American Economic Review, entitled “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development”. It proposed that Europeans established very different institutions in different colonies, as shaped by settler mortality. In congenial climates, they settled and built inclusive institutions, which enabled long-run prosperity. Acemoglu has massively transformed Economics by motivating empirical studies of institutions.

When he speaks, Economists listen. Mid-way through 2024, Acemoglu already has over 10,000 citations. This is not blind loyalty: his work is technically innovative and focused on important questions. Given Acemoglu’s track record, every publication gets attention.

MIT attracts the brightest minds worldwide, following the footsteps of Robert Solow and Paul Samuelson. Minted PhDs then secure tenure-track posts in top departments: adopting respected methodologies; teaching Acemoglu’s ‘Introduction to Economic Growth’ and Olivier Blanchard’s ‘Macroeconomics’. Prestige bias is institutionalised.

Elon Musk’s Tech-Euphoria

In their new book, “Power and Progress” Acemoglu and Johnson make a similar case about status and ideological persuasion: superstars of the tech world are widely revered, even by journalists who fawn at Elon’s feet. So instead of questioning the underlying ‘vision’, we marvel at a slightly different iPhone.

CNBC reporter Uptin Saiidi observes,

“When Elon Musk speaks at an event, crowds gather like it’s a rock concert… During the SpaceX update of plans to send humans to Mars, Elon Musk was interrupted by one of several thousand audience members, who yelled, “You can do it, Elon!”

Kim Kardashian’s Curves

What Acemoglu has done for institutions, Kim Kardashian has achieved for butts, catapulting buoyant derrières into global esteem. Both are ‘superstar influencers’, emulated as pinnacles of success.

Now what about religion? Whose words carry weight?

For the Roman Catholics, it’s clearly the Pope. As head of the Church, his moral teachings are widely revered. And that’s consistent with Acemoglu’s emphasis on institutions.

Arab Prestige Bias

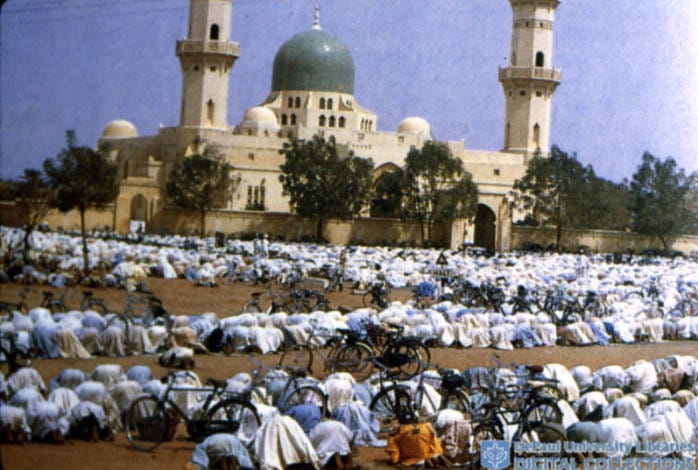

The most prestigious imams have always been those trained in Egypt or Saudi Arabia. Cairo’s Al-Azhar University has been a prominent centre of Islamic learning since the 10th century. It’s the Islamic equivalent of MIT.

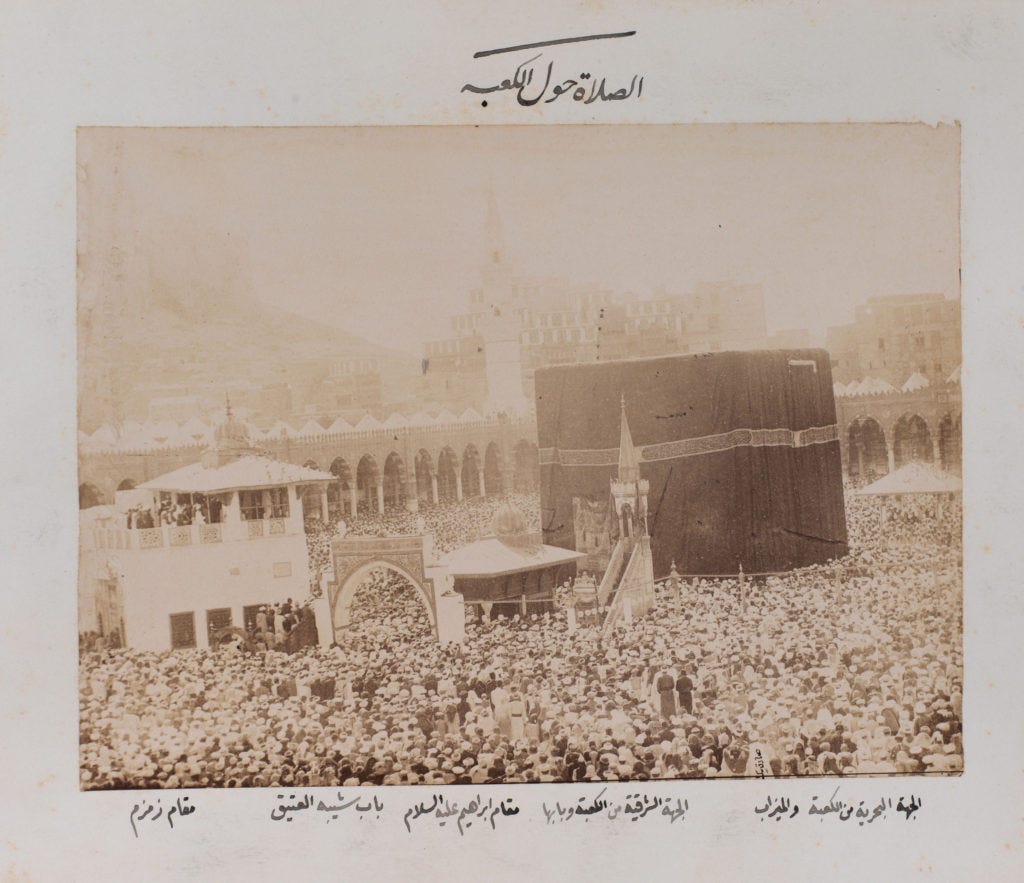

The Hijaz has long been a sacred place of pilgrimage and religious learning. Mecca houses the Sacred Mosque, Medina has the Mosque of the Prophet; both have attracted scholars from around the world. The great Islamic empires - the Abbasids, Mamluks, Ottomans, and Mughals - provided financial aid to Mecca as a display of piety. In return, Mecca conferred legitimacy upon ruling sultans.

But for most of Islamic history, Sub-Saharan Africa and SouthEast Asia were cut off. Pilgrimage was a sacred duty, yet prohibitively expensive. Even if peasants sold their land and sacrificed everything, journeys were plagued by bandits, disease and shipwrecks.

Technological Innovations

The 20th century heralded a revolutionary process of transnational learning, fuelled by technological innovations. Rotary printing presses facilitated the publication of hundreds of books, newspapers, and periodicals in Aleppo, Cairo, Mecca, and Delhi, which were then exported via steamships to bookshops in Penang, Ipoh, and Kuala Lumpur. Malay Muslims could now undertake the hajj, bring back new ideas, and establish reformist movements.

Foreign students typically studied in Mecca with a scholar from their country, eventually mastering Arabic and joining study circles in the Haram Mosque. The Hijaz was a focal point for scholars from around the world, who returned home with ‘spiritual capital’ and often spearheaded reform.

Railways, roads, radio, cassettes, and print media turbo-charged connectivity, amplifying da’wah missionaries. Pious students - in Nigeria, Indonesia and Malaysia - leveraged new media to study the righteous path. Malay Muslims published stories, newspapers, and magazines. The periodical Al-Imam sought,

“to remind the forgetful, to arouse the slumber, to guide those that have been led astray and to give voice to the wise.”

Struggles over Arab Prestige

Arab prestige bias made the Arabisation of the Muslim world highly probable, but the precise form was bitterly contested throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

The brief Wahhabi control of the Holy Cities (1803-1813) marked an aggressive imposition of their ideology, including the destruction of Sufi texts. However, this dominance was short-lived, and was subsequently criticised by scholars in Hijaz. The Ottomans reasserted control, going so far as to ban Wahhabis from pilgrimage to Mecca.

This ideological tug-of-war persisted into the 20th century. In 1924, Abdul-Aziz ibn Saud’s forces violently seized power, then institutionalised Wahhabism through state-approved syllabi and examinations, outlawing Sufi rituals.

Elsewhere, the fall of the Ottoman Empire triggered a counter-movement: Arab modernisers, seising upon the clerics’ loss of legitimacy, pushed for secularising reforms in an attempt to emulate the West.

However, secularisation was ultimately discredited by economic stagnation. Simultaneously, women’s increasing presence in the public sphere sparked a religious backlash. Gender segregation, promoted by religious publications, became a cornerstone of the Islamic revival.

Was this outcome inevitable?

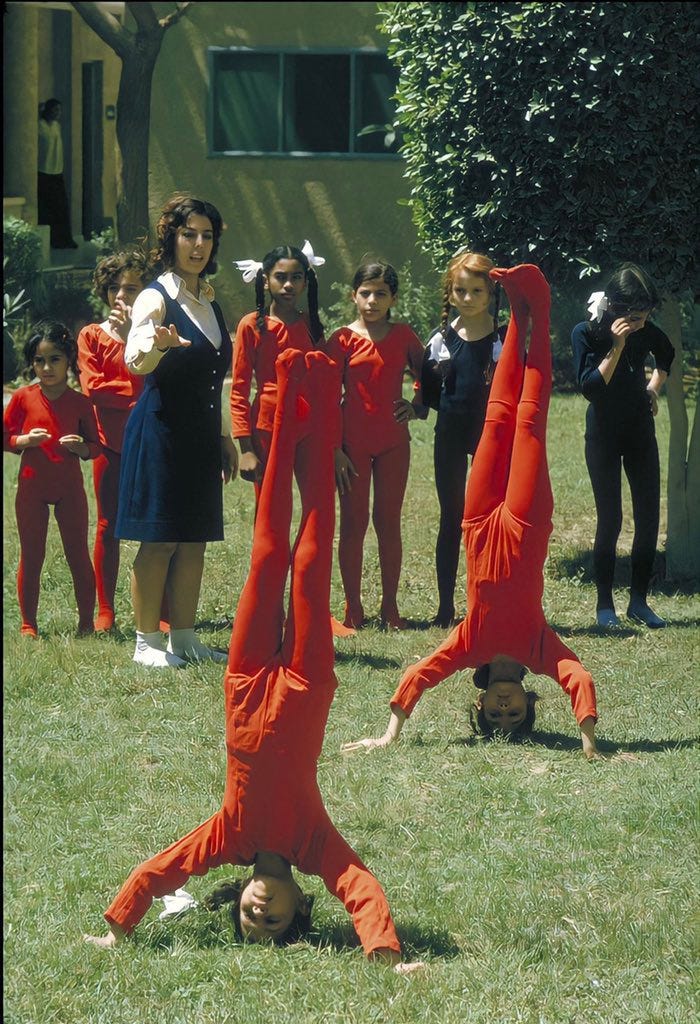

Consider that in 1960, female labor force participation rates were strikingly low across the Arabian peninsula, averaging about 6%. Throughout the Middle East and North Africa, the average was only slightly higher at 22%. Male honour was deeply contingent on female seclusion, and attempts at secularism in countries like Egypt, Iran, and Iraq were often imposed by force.

While cultural liberalisation briefly occurred, the odds of success were low. Most Arabs idealised gender segregation, a view that was subsequently adopted by Muslim communities in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asian Fatwas became Arabised

In the early 1900s, Southeast Asian Muslims requested fatwas from the ulama in Mecca. Evidently, they wanted to follow the righteous path and believed that was best known by muftis in Mecca. A 1908 fatwa published in Singapore, from Mecca, advised on the conditions in which you can buy children from kafirs (non-Muslims) and make their daughters your mistresses.

Harnessing the the latest advances in technology and communications, Malay Muslims also shared religious news from the Middle East and North Africa. Pengasuh (published by the Kelantan Council of Religion), repeatedly praised Al-Azhar as the pinnacle of Islamic education, building its global brand.

Al-Azhar was held in such high regard that its muftis were frequently referenced as guiding authorities. For example, during the conflict between Sharif Hussain and Ibn Saud in the Hijaz, Pengasuh repeatedly published the opinions of Al-Azhar ulama to convince Malays that Wahhabis were part of the Sunni Muslim community and not contrary to any of the four madhhabs. The same journal promoted Al-Azhar ulama’s criticism of Mustafa Kemal’s secularisation.

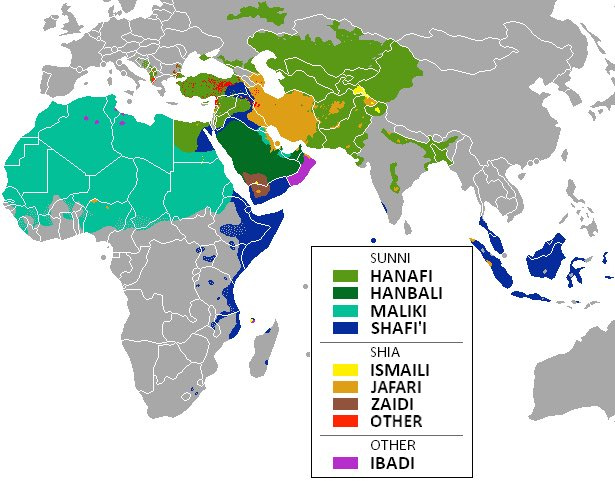

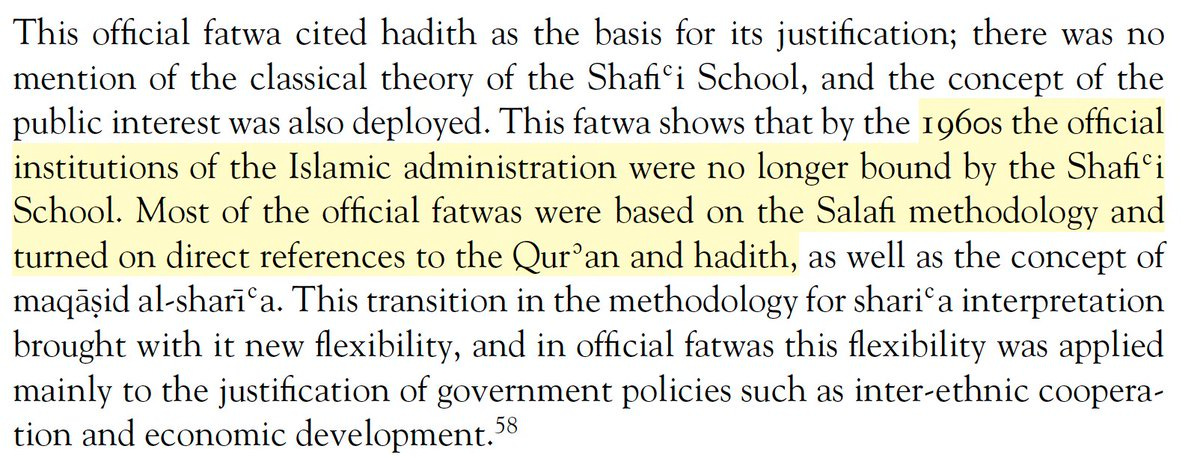

When Southeast Asian muftis issued fatwas (legal opinions) in the early 20th century, they drew on jurisprudential school of Shafi’i. By the 1950s and ‘60s, fatwas were markedly Salafist, as promoted by graduates from Al-Azhar.

Thus even before Saudi Arabia’s oil wealth and geopolitical alliance with the US, Malaysian scholars were embracing Salafism.

al-Azhar - the Islamic equivalent of MIT

As transport improved and incomes rose (especially during the 1920s rubber boom), Southeast Asian students increasingly travelled to Cairo. By 1925, 200 Southeast Asian students attended Al-Azhar. Malay students in Egypt established their own journals. One of the most influential was Seruan Azhar (Call of Azhar) - established in October 1925, widely read by religious leaders and students throughout the Malay archipelago.

By the end of the 1970s, over 3000 Malaysian students were enrolled in al-Azhar. Returning graduates graduates championed religious purification. Prestigious credentials (much like MIT on your CV) enabled them to become influential voices - shaping religious education, public debate and even government policies.

As detailed by historian Khairudin Aljunied,

“the improved communications in Malaysia made Muslims more conscious of the backward nature of their communities and beliefs…

They derived intellectual inspiration from global intellectual, political and religious streams of thought which they were plugged into.. [Reformists wanted] to critique and purify the adat [custom] and religious practices from bid’ah (innovations) and khurafat (animistic superstition) that characterized the Muslim faith.”.

al-Azhar’s curriculum and textbooks have been adopted worldwide. In Malaysia, the religious school system that trains ulama (Islamic scholars) follows guidance from Al-Azhar. Once students have passed the final exam, they can study at al-Azhar. Although 5000 miles apart, the two educational systems are now closely aligned.

Over 30,000 foreign students are currently enrolled in Islamic Studies at al Azhar University. Eager to study at the Muslim equivalent of MIT, undergraduates come from across the world: 4000 from Africa, almost 3000 from Russia, 5000-plus from Malaysia, and 400 from the UK.

Google Trends provide a valuable insight into revealed preferences. What do people want to learn about? What are their genuine interests? As you can see, Al-Azhar’s continues to grow.

Al-Azhar's Reach: Cairo to Casablanca

Al-Azhar University influenced Morocco’s nationalist movement and educational system.

In the early 20th century, ideas from Al-Azhar trickled into Morocco through a couple of channels. Moroccan scholars studied at the prestigious institution; merchants and pilgrims passed through Cairo; and a few Egyptian newspapers found their way into the hands of Moroccan elites. But information flows were still very limited.

Enter Abu Shuʾayb al-Dukkali, an Al-Azhar graduate who returned to Morocco in 1907. The time was ripe: Islamic modernism resonated widely. Morocco was facing political instability, economic crises, and the looming threat of French imperialism.

Once in power, French colonisers introduced secular schools, triggering unease. Post-independence nationalists wanted to Arabise education in order to reclaim Moroccan cultural identity. In the 1970s, King Hassan II supported Arabisation partly as a strategy to counter leftist movements on university campuses.

The appeal of Western modernisation further weakened amid economic stagnation, and over the 1970s Moroccans increasingly sought guidance from al-Azhar.

The lesson from 20th century Morocco is that prestige bias is actually malleable and contingent. Cultural and political entrepreneurs seek to persuade their publics, and may be more convincing in specific circumstances (such as when people face a shared threat, or alternatives like Western modernisation are discredited).

Modern Communications

Soon after starting his Twitter account, Daron Acemoglu had amassed a quarter of a million followers. Kim Kardashian’s fanbase is even bigger: 362 million on Instagram. Modern technology enables people to learn from their heroes - whether that’s in terms of Econometrics, sparkly dresses or Islamic jurisprudence.

Technological innovations similarly increase global access to al-Azhar. Back in 1931, the university circulated its wisdom via the monthly Al-Azhar Magazine. Today, Azhari scholars share insights on Islamic TV - like Al-Jazeera and the UK’s Islam Channel.

No one is being forced to watch, none of this is propped up by authoritarians or social media algorithms. Global popularity reflects genuine demand. When asked whether al-Azhar’s audience is primarily domestic or international, senior scholars insist:

Global demand for fatwas from al-Azhar remains extremely strong, reflecting its prestige. Muslims from around the world want guidance from the Grand Imam. When Sarkozy introduced the hijab ban, he sought approval from al-Azhar, knowing this would be respected by Muslims in France. Likewise in modern Britain, callers seek guidance from scholars educated at al-Azhar - their version of MIT.

al-Azhar has also introduced a telephone hotline in various European languages, in response to demand for fatwas from Muslims in the West.

The Islamic University of Medina’s influence in Kano

The Islamic University of Medina (IUM) was established in 1961 by royal authority. Teachings focus on the Hanbali school of law, which derives its rulings from the Quran and the Sunnah. Core tenets included:

Emulating the ‘pious ancestors’ (the Prophet, his followers and their kin, i.e. prestige bias)

‘Tawhid’, the unicity of God, and the view that many traditional Islamic practices are illegitimate (‘shirk’, ‘polytheism’)

Forbidding wrong, combatting ‘shirk’; purging illegitimate innovations (bidda)

The Quran, sunna, and consensus of the Prophet’s companions are the only legitimate source of religious authority.

Oil wealth enabled wider enrolment - attracting students, who were already eager to study and socialise in the Prophet’s Mosque. The IUM’s budget soared from 40 million Saudi Riyals in 1975 to over 381 million in 1982 (i.e. USD 111 million). Student recruitment totalled 3,100. By the late 1990s, the university had spent an estimated USD 1,400 million.

Foreign teachers became a major presence. In the early 1980s, faculty included over 130 Egyptians, as well as Sudanese, Syrians, Jordanians, Iraqis and Indians. Many had also studied at al-Azhar. Global diversity bolstered IUM’s legitimacy and quest to define Islamic orthodoxy.

Unorthodox creeds were attacked, e.g. refuting Ahmadis, Shi’a, Sufism, visiting shrines and tombs, as well as seeking the intercession of saints, using charms, and sorcery. Instead, students focused on al-Wahhab, the Hanbali tradition, and the Salafi method.

Rewards and punishments were closely tied to student exam performance. Failures could be expelled, while success was congratulated with financial stipends. One student who arrived in Medina in the early 1990s recalled that classroom desks were allocated according to test scores, with the highest achievers at the front.

Nigerian students travelled to Medina, to strengthen their command of scripture and learn from the best. In 2012, over half of Kano’s most prominent Salafi preachers were graduates of IUM. Impressive credentials meant they quickly amassed followings, established new institutions and influenced politics.

Prestige Bias Drives Cultural Assimilation

The 20th century's technological innovations in media and connectivity opened unprecedented avenues for transnational learning and ideological persuasion. However, contrary to expectations, free media did not always lead to cultural liberalisation. Some societies have even become more socially conservative.

This phenomenon can be explained through the lens of prestige bias - people's tendency to emulate those perceived as successful within their communities. Prestige is not just about individual celebrities; it’s perpetuated through institutions and networks. For instance, MIT economists have achieved multiple Nobel Prizes, in turn attracting bright minds who go on to publish in top journals and lecture at the best departments, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of influence.

In the Muslim world, this prestige bias has manifested in the growing influence of traditional centres of Islamic scholarship - Mecca, Medina, and Cairo. The respect accorded to imams trained at these institutions, coupled with new communication technologies, has led to a notable Arabisation of the previously diverse Islamic world. Even in wealthy nations like the UK, Muslim communities often look to al-Azhar.

My emphasis on prestige bias is somewhat unusual. I suggests that cultural change is neither solely driven by social movements nor economic development. Instead, it’s significantly influenced by who a community deems prestigious - a status that’s always contested (just look at Kendrick Lamar’s diss tracks).

What’s the difference between MIT and Mecca?

Economics is known for hostile questions; no one is above critique. In contrast, Mecca and al-Azhar have certain ‘red lines’. Scholar Yasir Qadhi explains,

“There are clear red lines that the seminary is not going to cross…

It’s not just the texts [the Quran] that are beyond question; every seminary is of course coming from an established sect or paradigm; every seminary is not only Muslim-based, it is sectarian-based.

You are not even allowed to challenge that version of Islam, much less the religion of Islam, that is the default of the established seminaries.. the ones which are perceived to be the orthodox or the originals or the most prestigious.

They are not just coming from faith-based, they are coming from coming from a particular understanding within the faith”.

What does this mean for Muslim feminists?

Islamic credibility remains contingent on conforming to established scholarly consensus - from the Arabian heartland. This trend, driven by historical prestige, has encouraged gender segregation, homophobia, and illiberalism. Arabisation thus creates major new barriers for Muslim feminists, as discussed in my previous essays:

How is Saudi-funded Salafism changing the fourth largest country in the world?

Modern Threats and Religious Backlash (on Egypt and Saudi Arabia)

Piety and Modernity: Navigating Islamic Traditions in 21st Century Britain

Why are Conservatives Winning? (on British Muslims)

Related Essays

Rocking Our Priors

"Practicing Islam in Egypt" and "Salafism": Podcast with Aaron Rock-Singer

“Islam and Citizenship in Indonesia” Podcast with Robert Hefner