An Intellectual History of the Patriarchy

The vast majority of innovations, companies, and governments are under male authority. Why is this? What led to it? In this piece I crudely synthesise debates on the origins of the patriarchy.

Although there is a wealth of research on gender - in different places and time periods, from siloed disciplines and methodologies - it is like a mountain of mosaic pieces. What we have now is millions of fragments. So, let me take a stab at building the mosaic, incorporating insights from archaeology, anthropology, economics, genetics, history, psychology and sociology.

If you'd rather listen, here's the podcast.

The Rise of Gender Studies

Until the 1960s, the social sciences were dominated by men, who typically ignored women. Grand claims went unchecked. The patriarchy was presumed to be universal, often attributed to biology and women’s confinement as care-givers. Susan Brownmiller emphasised worldwide male violence. Simone de Beauvoir proclaimed “this has always been a man’s world”. Others like Marija Gimbutas posited ancient matriarchies and goddess worship.

Over the 1970s, anthropology and archaeology became increasingly feminised and politicised. Struggles for sexual revolution on the streets fostered feminist consciousness in academia.

In New York, Boston and Norway, female graduates rallied to discuss the latest publications. Together, they collectively re-affirmed and legitimised gender as a valid object of scientific inquiry. They also institutionalised gender studies, by mentoring young women, editing books, and teaching courses on cross-cultural variation. This was an ideological mission: if they could identify the drivers of patriarchy, they could change the world.

Correcting male-biased scholarship was another guiding objective. Prior research had largely been written by men about men. Male anthropologists were faulted as blinkered to women’s hidden powers and areas of influence. Feminist archaeologists, historians and anthropologists made women visible: demonstrating their importance, contributions, and agency.

As academia diversified, second-wave scholarship was increasingly lambasted as privileged, white and heteronormative. It was blinkered to differences between women. Black, working class and non-Western scholars drew attention to intersecting structures of dis/advantage.

As empirical studies burgeoned, assumptions of universal male dominance were debunked and discarded. Gender relations were increasingly shown to be globally heterogenous. The central questions became,

When, where, and why had women become oppressed?.

Debates on the Origins of the Patriarchy

Below I crudely condense this entire literature into 7 chronologically ordered hypotheses.

BIOLOGY. Evolutionary psychology argues men evolved to control female sexuality as a means of maximising parental certainty, while women evolved to seek dominant providers (Buss 2016; Smuts 1995). Testosterone explains men’s heightened competitiveness and aggression (Hooven 2021). Child-bearing made women dependent on men (Firestone 2015). Child-care also limits women’s skill-acquisition, workplace commitment and career stability. This all encourages statistical discrimination.

PLOUGH-CULTIVATION conferred an advantage on men. Since men were physically stronger, they ploughed the fields, while women processed cereals. This heightened female domesticity. In non-industrial societies where women contribute a larger share of calories (through foraging), women maintain economic power. Girls are seen more favourably and pre-marital sex is permitted. Women’s childcare and food preparation was vital, but they became economically dependent on marriage. Families taught their daughters to be submissive, to get a good husband.

PATRILINEAL CLANS formed to defend valuable land from attacks, where intensive agriculture raised population density and created land scarcity. Wealthy landowners bequeathed land and herds to sons. Men gained value as strong warriors.

PRIVATE PROPERTY facilitated men's exploitation of female labour. As men accumulated wealth, they monopolised the surplus and institutionalised patrilineal inheritance. Men had always controlled the means of production, but amassed even greater advantage through private property.

BRIDES COMPETED for wealthy grooms by signalling chastity and relocating to the groom's clan. Cattle-based agricultural societies became patrilocal because women preferred this to destitution. Women increasingly cloistered, lacked independent social networks and became economically dependent on men. Men entrenched their authority through moral codes.

STATE-DEVELOPMENT undermined kinship systems. Women lost authority as sisters and became dependent wives. Powerful states also restricted women to the domestic sphere in order to maximise social reproduction

COLONIALISM strengthened male advantage, the nuclear family, and female domesticity. Colonial officials favoured men in agricultural training and wage labour, while Christian missions promoted female domesticity. Women became more dependent on male breadwinners and lost roles as religious leaders.

What Don't We Know?

These claims suffer from several methodological weaknesses. As monocausal explanations (respectively emphasising genes, private property, colonialism) they all ignore the cumulative effects of multiple factors.

Second, these all purport to explain a global phenomenon, but either extrapolate from unrepresentative qualitative case studies or use cross-sectional regressions to spin tales of causation.

There has been a flurry of valuable persistence studies. These examine the effects of X on Y. They do not investigate the other causes of Y.

In the absence of comparative historical research over ten thousand years, we don’t know their relative importance, causal mechanisms or cultural evolution. Cardinal questions remain unanswered.

Were foragers really so gender equal?

Attempts to identify “the origins of patriarchy” assumed a pre-Neolithic feminist utopia. Yet if recent studies of foragers are any guide, during the 100,000 years that our ancestors had spent as hunter-gatherers, girls may have been forced into marriage (often polygynously), beaten and raped.

How did socioeconomic stratification intensify gender inequality?

Socioeconomic stratification is positively associated with sexual hierarchy among pre-industrial societies. But what are the causal mechanisms?

Strong men became important for subsistence agriculture

Patrilineal clans formed to protect valuable land and herds

Men exploited women’s labour and instituted patrilineal inheritance

Women competed for wealthy grooms with displays of chastity.

Why no mention of honour?

Researchers who lack in-depth understanding of every single society cannot build global theories. Blinkered by their own priors, 1970s Marxist feminists tended to emphasise men's exploitation of women's unpaid domestic labour. But the obstacles to female wage labour are globally heterogenous. In Ancient Greece, Southern Mesopotamia, Mughal India and Song China, patrilineal clans cloistered female kin in order to preserve their honour. Female wage labour was shunned for fear of inevitable stigma, suspicion and loss of status. This ideological prescription imposed a totally different constraint to the time burdens of childcare. Marxists failed to recognise this global heterogeneity.

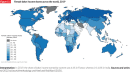

What caused the Eurasian divergence?

Patriarchy is often dated to the Neolithic, but geographical determinism fails to explain change over time or heterogeneity between similar ecologies. Plough and cereal cultivation were the dominant modes of production across the whole of Eurasia. Yet in this very same geography, Ancient Egyptian women socialised freely, with scant concern for virginity, and commanded respect as priestesses to female goddesses. Why - thousands of years later - did Egyptians come to idealise female seclusion? How did Europe eventually emerge as more gender equal? What explains the Eurasian divergence?

What about religion?

During the 1970s hey-day of this literature, second-wave feminists were heavily influenced by Marxism. They largely neglected cultural evolution and religion.

Christianity was once extremely patriarchal, but today is associated with greater gender equality (more so among Protestants). The Quran has many egalitarian aspects, yet contemporary Muslim countries tend to be governed by men. In pre-colonial Philippines, women enjoyed pre-marital sex, travelled widely as traders, owned land, divorced freely, worked as royal bodyguards, held high office, led worship as priestesses, and were worshipped as goddesses. Their religious importance was eroded by Catholicism.

Where and how did colonialism exacerbate gender inequalities?

Colonialism is often said to have exacerbated gender inequalities, but causal mechanisms remain clouded. Development generally leads to female emancipation, and imperialism has inhibited development and democratisation in the Global South. But it may not be the sole cause of sexism.

In the Middle East and North Africa, female seclusion was the norm long before colonialism and remains far more pervasive in the region than in other countries with similar wealth.

In Latin America, many indigenous people fiercely maintained their own traditions. Andean non-elite permitted pre-marital sex and deemed trial marriage necessary for long-term companionship. Women continued to work, own, inherit and bequeath property. They also participated in their local religious life and led protests.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, colonial bureaucracies were tiny, state penetration was weak, agricultural support was meagre, technological upgrading was minimal, and labour markets were miniscule. Imperialism did not benefit most African men, so cannot have radically heightened their advantage. Moreover, even if a few men gained temporary benefits, Southern and Eastern Africa now have some of the world's most gender equal parliaments. This suggests that colonialism did not cement long-run inequalities. There could be other reasons why West African parliaments are now overwhelmingly male.

To understand the emergence of patriarchies in different parts of the world, we need to harness the wealth of existing research on gender and apply comparative historical analysis.

We must build the mosaic.