"City of Men" by Romit Chowdhury (Review)

Patriarchy is often studied by focusing on women - their aspirations, education, fertility, housework, and labour market participation.

But what about the men? If we grant that men are in positions of authority, then surely we need to understand their beliefs and desires? What motivates men?

Romit Chowdhury has just published an astutely observed ethnography of Kolkata (with beautiful illustrations by Subhajit Das). Join me to discuss “City of Men”.

Economic immobility

“In my exchanges with transport workers, I was struck by the number of operators who stressed that the city of Kolkata has not changed substantially over the years: “Yes, roads have improved, overpasses have been built, there are much more private cars, living here has become more expensive but nothing has really changed for me” (forty-three-year-old driver)... Many young auto drivers reported that their fathers had been operators too during their working days and that they did not see any qualitative improvement in their lives through this generational shift. Much of their fathers’ difficulties to earn and provide sufficiently for their families remained their struggle as well”.

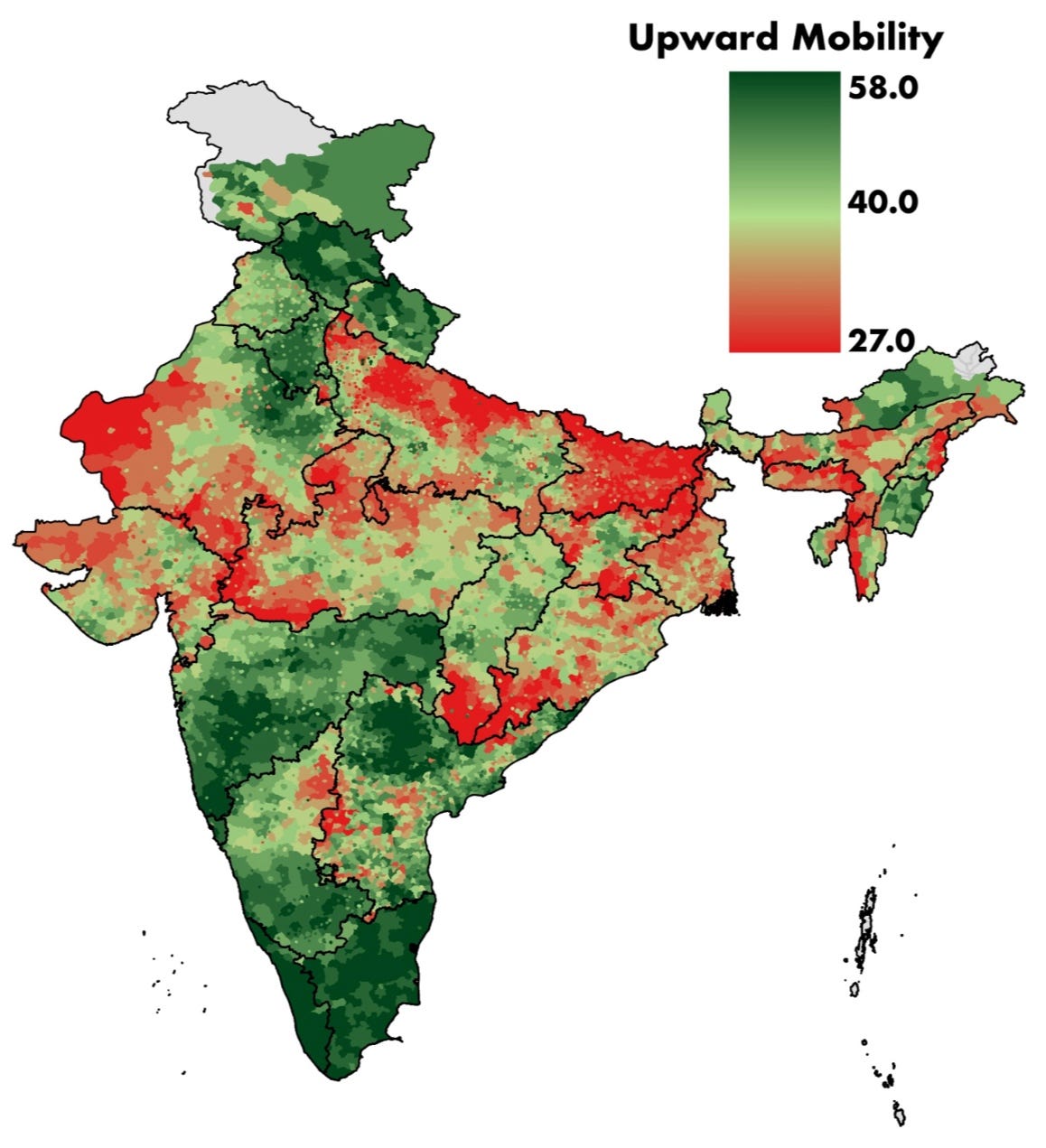

This tracks Kolkata’s low upward mobility.

Sam Asher, Paul Novosad and Charlie Rafkin actually quantified the geographical distribution of upward mobility across Indian subdistricts. This map shows the expected national education rank of a son born to a father in the bottom half of the parent education distribution. Kolkata scores poorly.

This is important, because Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira and Stefanie Stantcheva have a new paper showing that people who have experienced very little intergenerational mobility tend to believe the world is ‘zero sum’: your success is my loss.

I suspect that belief may be compounded by India’s rising income inequality. The 43 year old driver is acutely aware that others have thrived, while he remains trapped.

Male Breadwinners

By migrating to Kolkata where there are more work opportunities, men are more able to fulfil their idealised roles as providers.

“These days when I go back to Bihar I feel astonished sometimes. There’s just no work…That what makes me glad about being in Kolkata; at least I get to earn here” (38 year old taxi driver from Saran district).

Social Networks and Family Honour

Cities are often celebrated as enabling escape, anonymity and freedom. Romit Chowdhury suggests this is inaccurate. The regular flow of workers and information between Kolkata and rural Bihar mean that stories of impropriety soon circulate.

Chowdury writes,

“The fear of being morally shamed and its far-reaching impact on their families in the village influence migrant drivers’ moral choices in the city”.

Mukul (a 21 year old taxi driver from Gaya district) remarked,

“Even if news of a small matter about something that I have done here goes back home, my parents will commit suicide out of shame. So I stay clear of wrong paths.”

Bihari migrants expect information to get back to the village, possibly damaging family honour, and take great care to prevent rumours.

[I would add that smart phones and Whatsapp messaging may have actually heightened urban-rural surveillance].

Men’s Inability to Provide is Shameful

“No woman in my family has ever worked. My mother has not worked. The wives of my elder brother don’t work. But it’s true that expenses have gone up so much in the past few years that it would be good if my wife worked as well. But I hesitate to ask her. I feel a sense of shame. As if I have failed in my duty” - (autorickshaw driver).

This is a crucial point! In societies where men gain respect through household provision, their wife’s employment becomes deeply embarrassing.

This tracks labour market data. The poorest, lower-caste families have little to lose and regularly sacrifice social respect for the sake of barebones survival. In rural Uttar Pradesh, women only turn to waged work under the most desperate conditions. Yet once family finances improve, women withdraw from the workforce and ‘buy’ some respectability again.

Claudia Goldin similarly emphasised ‘stigma’ to explain why female employment was so low in industrialising America:

“The stigma is a simple message. Only a husband who is lazy, indolent, and entirely negligent of his family would allow his wife to do such labor”.

Men from rural Bihar explained that they came to Kolkata alone because of ‘dharm-nash’ (the sin of taking a woman of the house to the city). They want to maintain respect, and they feel a sense of prestige in being able to keep their wives at home.

Religion

In Hinduism, dharma refers to what is ethically correct, our duties and obligations. Men are seen as morally responsible for their families’ protection and provision - suggests Chowdhury.

He does not mention this, but the Quran also emphasises men’s responsibility to provide:

“Men are the caretakers of women, as men have been provisioned by Allah over women and tasked with supporting them financially” (Surah An-Nisa, Chapter 4: Verse 34).

A good Hindu/ Muslim man provides for his family. His wife’s employment is thus stigmatising it reveals his failure to be a good Hindu/ Muslim. This may help explain why Indian men are often more supportive of their daughters than wife’s employment.

Only by understanding morality - suggests Chowdhury - can we grasp why South Asia’s cities have become the preserve of men:

“Men’s mutual regard for their provider role, its importance in the survival of their families and their own social worth, creates a culture of morality on city streets that is premised on homosociality” (Chowdhury 2023).

City Streets are Men’s Terrain

Men recognise and respect each other as providers - sacrificing for their families, and thereby achieving status - explains Chowdhury. City streets thus become recognised as men’s terrain, while encroaching women are deemed out of place.

“Women in the city - as temptresses or as claimants on the urban labour market - are seen as detracting from male breadwinning. Thus, if the image of women in public spaces persistently evokes anxiety and rage in Indian cities, these reactions are to be partially explained by a homosocial culture of the street in the region that invests enormous moral value in men’s provider role, a powerful index of masculinity that is itself tied to the city” (Chowdhury 2023).

This is a fantastic point, and I believe it may be exacerbated by ‘zero sum mentalities’. If men have not experienced economic mobility and believe the pie is finite, they may be especially opposed to female incursions.

“City of Men” is out now! I loved it and learnt a great deal. Bravo to Romit Chowdhury!