Why is Indian Women's Welfare Devalued?

Two brilliant new films - “The Great Indian Kitchen” and “Mrs” - illuminate a fundamental aspect of patriarchy: the expectation that women silently serve their families, without recognition or reward. But why do these domestic inequalities persist in modern India?

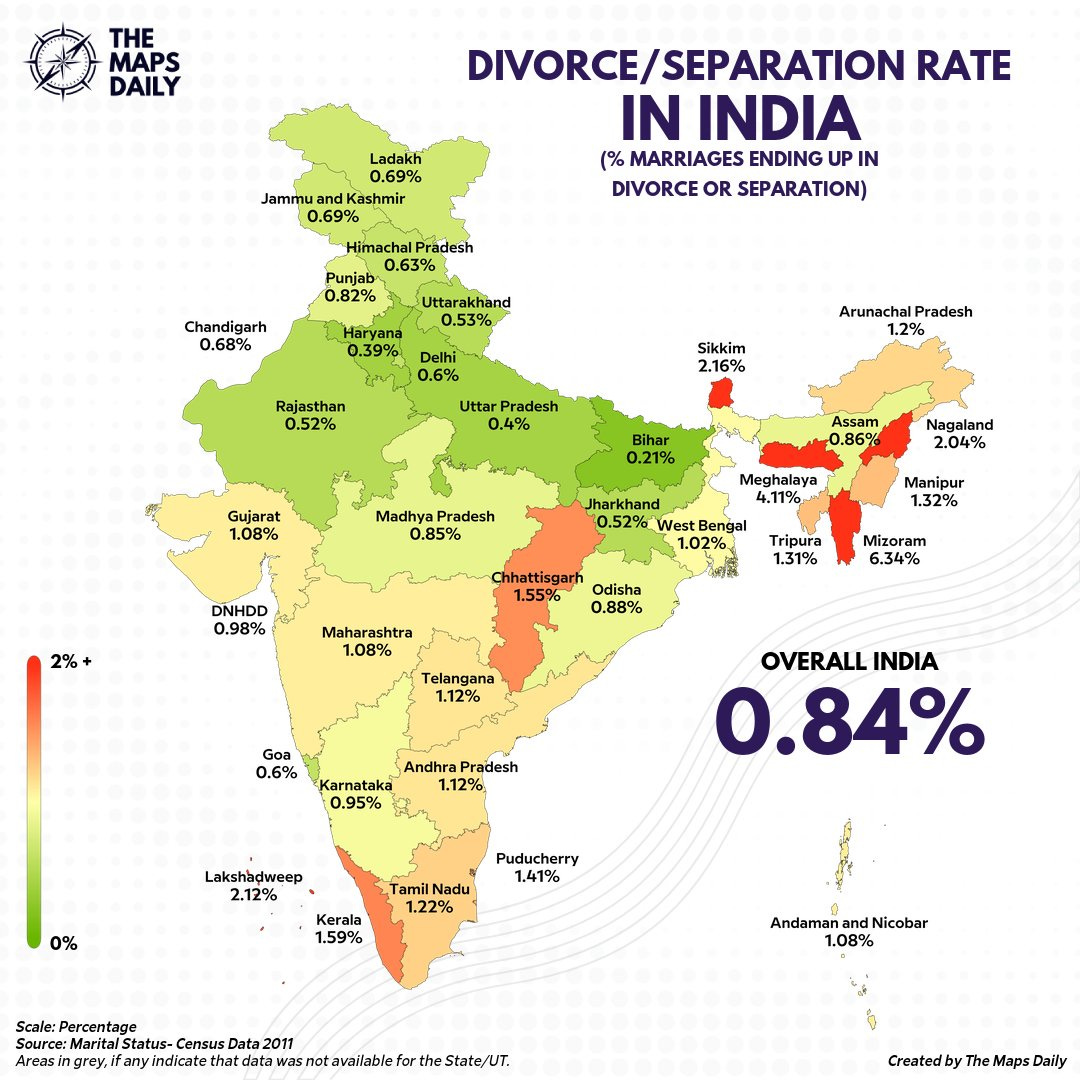

Through my interviews with men and women from across six Indian states, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Morocco and Turkey, I’ve developed the concept of “The Patrilocal Trap”. Historically across Eurasia, sons inherited family assets and cared for elderly parents. Families maintained trusted networks through strategic marriages, socialising daughters to marry, please their in-laws, and stay put. Divorce is heavily stigmatised.

If women are raised for loyalty and unable to credibly threaten exit, they may not necessarily challenge men’s patriarchal entitlements. Instead, she may quietly comply. These films brilliantly capture what quantitative research often misses: the systematic subordination of women's time, preferences, and wellbeing to men’s comfort and convenience.

“The Great Indian Kitchen”

“The Great Indian Kitchen” is set in Kerala - which in many ways was India’s best case scenario for gender equality. After an arranged marriage, Nimisha (the protagonist) joins her mother-in-law to serve the father-in-law and husband. Together, they laboriously grind spices, preparing elaborate meals with infinite varieties of thalis. Never do the men convey thanks, nor do they make the women feel appreciated. But they always leave a mess.

Nimisha and the mother-law eat apart from the men - not enjoying their glorious thalis, but making do with simple daal. Whenever the father-in-law wants to perform a basic task (like brush his teeth or leave the house), his wife brings him whatever he needs. When the mother-in-law leaves to visit her daughter, all the domestic drudgery falls on Nimisha - who is then constantly cooking, cleaning, and sweeping. If you started watching mid-way, and assumed the women were servants, it would be perfectly believable.

Despite the family being comfortably middle-class with modern appliances like rice cookers and washing machines, the father-in-law insists Nimisha perform all work by hand. Men’s preferences consistently trump her time, wants, and welfare.

Some economists claim that India’s female labour force participation is low because women are busy with housework. In reality, the volume of housework is determined by patriarchal expectations.

When Nimisha appeals to her natal family for support, they advise compliance. When she tells husband Suraj that sex is painful and suggests foreplay, he reacts with mockery.

During her period, she’s declared ritually impure and quarantined in an outbuilding. When she attempts minor rebellion by sharing a feminist Facebook post challenging menstruation stigma, Suraj’s friends quickly intervene, suggesting he imposes control.

While fictional portrayal aligns with nationally representative data on intimate partner violence. As I visualise in the maps below, only 11% of Indian women who have been beaten by their husband have sought help. Most stay silent.

Jalota and Ho’s randomised control trial in Mumbai provides further evidence of men’s prerogative. 63% of slum-dwelling women initially accepted job offers, but many subsequently backtracked. What happened? They spoke to their husbands who refused.

“Mrs”

“Mrs”, a Hindi adaptation starring Sanya Malhotra that premiered on Zee5 last month, has generated significant public debate. Feminists have praised the film for highlighting everyday emotional abuse.

The film’s comments section reveals its resonance:

“This was a huge thing in my extended family too - they all used to say raaita should be made hand-whipped and not in a blender. I grew up hearing these things but never internalised thankfully and it made me realise that patriarchal households hate any advancements that make women's lives easier but not the technological progress that typically helps men”.

“This was such a hard hitting movie. Even if you don’t relate to the subject it‘ll still leave you feeling so frustrated. It’s the honest truth about the issues women face in their daily lives”

“Almost everything shown here is a common occurrence, especially when living with in-laws. Women are taken for granted and basically treated as a house help without the salary”.

Patrilocal Trap

Last month, I was invited to join a WhatsApp group of 600 young Indian women university students. Generously, they’d asked me to participate in a Zoom discussion about my research on romantic love. Curious to hear their perspective on “The Great Indian Kitchen”, I polled the group on whether it was realistic? Even among these female graduates, the response was an overwhelming ‘yes’.

The Patrilocal Trap is especially potent in India because it intersects with caste. Jati networks provide crucial economic resources, making caste endogamy and indissoluble marriage essential for upward mobility. To quote an Urdu expression,

“Tumhara susral hi ab tumhara ghar hai

Tumhara Susar hi ab tumhara baap hai

Ab Tumhari Doli ja rahi hai ab susral say Tumhari arthi ay”

It means “Your in-laws' home is now your home, Your father-in-law is now your father, Your wedding palanquin is going now, and from your in-laws' home will come your funeral coffin”. In short, she stays there until death. But when wives cannot credibly threaten exit, they seldom contest men’s expectations of status.

While feminist cinema may help shift cultural expectations, my research suggests that continued reliance on caste may inhibit wider dissent.

Another stellar read!

I've been a fan of your blog for a while now, and was the main reason I signed up for Substack. Your analysis of the ‘Patrilocal Trap’ is a powerful framework that's stuck with me - cinematic and cultural tropes to bring those systemic issues to life is a great application of that lens.

As an Indian living abroad in a very different society (New Zealand), I've been thinking about another facet of our modern condition: the sense of "running in place" where institutional and cultural inertia keeps us from real progress. I’ve written a piece exploring this idea further, considering how even when it seems like change is happening, we might just be reinforcing the status quo.

It's written from a slightly different viewpoint of how class-coded expectations of leisure continue to hold Indian women back, but I’d love to hear your thoughts on whether this parallel holds up in your view. Here’s my take if you’re interested in checking it out:

https://csthinks.substack.com/p/running-in-place-with-distinction?r=1kld54

CS

I have a request. If you have time, watch the original work in Malayalam. The actress Nimisha Sajayan has done a tremendous job, and the movie was even recommended to the entire country by the then Supreme Court chief justice Dr. DY Chandrachud. I suggest the original because there are specific cultural-historical parts of gender bias that the original addresses. The Sabarimala issue (the temple is a celibate temple and therefore women, once they attain puberty ( menstruating ), are not allowed to enter or make sexual contact with men) was all part of the original.