How to Promote Equality without Backlash?

Not all cancer treatments work. Likewise, not all feminist activism is effective. So, we can ask,

What’s the best way to promote gender equality, without triggering backlash?

In 1960s Cairo, young women walked freely through university campuses in miniskirts. But this pushed too far, triggering backlash. Over in the U.S., progressive legislation has also proved antagonistic, heightening men’s sexism. Today in South Korea and Madhya Pradesh, feminist incursions spark violent hostility.

My comparative research reveals a global trend: threats to status, assaults on core values, and exclusionary tribalism can ignite organised resistance. All this is exacerbated by social media.

To advance gender equality, it may be more strategic to build inclusive campaigns that gently expand what is considered acceptable while appealing to common values. Gender interventions will have the greatest impact if they tackle locally-binding constraints, with careful sequencing. Delivering shared prosperity is equally vital - especially for disadvantaged young men.

What Drives Backlash?

Crudely, let me theorise three core drivers of backlash, before exploring how this resistance manifests in different regions.

Assaulting Core Values

Every society has a unique cultural inheritance with spectrum of permissibility. Progressive and conservative forces mobilise at opposite ends of this spectrum, each seeking ideological persuasion and institutional dominance. When either side pushes beyond what the median citizen considers acceptable, this can trigger organised resistance - like an elastic band snapping.

Exclusionary Tribalism

Tribal psychologies are a fundamental aspect of human behaviour - driving us to pursue group success, while emulating our peers and successful individuals.

Ultimately, we want our tribe to win. When people recognise that others possess competencies benefiting their tribe, long-held prejudices often dissolve. Watching the NBA, supporters may champion their team’s black players, while simultaneously expressing racist slurs against black opponents. When lower-caste cricketers secure team victories, they gain status. The crucial question becomes “Are you with us or against us?”

Since humans constantly look for signals of who’s ‘on their team’, exclusionary advocacy can stimulate divisions and resistance. Imagine if a group kept cheering for ‘the red jerseys’ while ignoring everyone else - it breeds resentment.

Status Threats

Status hierarchies serve as the foundation of patriarchal systems. At its most extreme, men are revered as knowledgeable leaders and spiritual authorities, while women are expected to serve and obey. If men’s community status hinges on their wives’ submission, they may react violently to public defiance.

Any of these mechanisms - assaults on core values, exclusionary tribalism, or status threats - make men more susceptible to countervailing movements that affirm men’s status. Now, exactly what constitutes a ‘threat’ varies by culture…

Regional Manifestations of Patriarchal Backlash

Let’s examine how these dynamics play out in different parts of the world, where the consequences of challenging gender hierarchies range from ostracism to retaliation.

South Asia

In tight-knit conservative societies, the spectrum of permissibility is very small, such that even small challenges can trigger violent resistance. In South Asia, men’s status rests heavily on two pillars: their role as breadwinners and their control over female family members’ public interactions. When women challenge these hierarchies, they may face blow-back.

Women participating in self-help groups and gender sensitisation programmes in Madhya Pradesh face increased public humiliation from their husbands. As Prillaman’s research shows, Indian feminist activism frequently triggers antagonism.

Experimental research in Bihar found that men were nearly twice as likely to financially penalise women who were introduced as participating in ‘empowerment’ programmes (17% versus 9%). This misogyny was most prevalent among men who accept or commit intimate partner violence. 40% of studies measuring reactions to women’s empowerment programs in developing countries find evidence of male backlash.

Economically, Indian women who have more education or higher earnings than their husbands have the highest likelihood of frequent and severe violence. Given the caste system’s hostility to divorce, victims tend to stay put - enduring violence.

Going forward, I hypothesise that India’s adverse sex ratios and declining fertility will make it impossible for some men to marry (and achieve status). This may breed misogyny.

The Middle East and North Africa

The Middle East and North Africa demonstrate how severe backlash can alter an entire region’s trajectory. In the 1950s and 60s, Arab modernisers’ attempts to secularise their societies initially gained traction among aspiring elites. But this breached the boundaries of permissibility.

As women entered universities and workplaces in growing numbers, clerics successfully rallied the masses against perceived threats. Western modernity lost further allure amid economic stagnation and military defeats. Struggling graduates found status-affirmation in religious brotherhoods.

The result? Men sought to restore order by demanding veiling, harassing women in the streets, and enforcing patriarchal dominance.

Resistance in Wealthy Democracies

Even in prosperous democracies, feminist campaigns can trigger counter-reactions. When states passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) - guaranteeing equal rights - American men became more sexist. Spain’s feminist movements similarly triggered hostile sexism and increased support for far-right politics.

In South Korea, sons were traditionally celebrated as providers and scions of the lineage. Yet today, graduates face brutal competition for white-collar jobs while adverse sex ratios make finding wives increasingly difficult. This mismatch between cultural expectations and reality seems to fuel resentment. Message boards overflow with misogynistic content, while feminist activism has triggered a surge in hostile sexism and the election of an ‘anti-feminist president’. John Burn-Murdoch’s visualisation precisely tracks this polarisation - showing how Korean men’s attitudes sharply diverged from women's following #MeToo.

Global Patterns: Economic Status Loss and Male Backlash

When men lose relative economic status - whether through industrial decline, recession, or women’s increasing workforce participation - they often respond with hostile sexism. This pattern appears consistently across diverse societies.

In the United States, when local industries feminised and blue-collar men lost relative economic status, they became more likely to endorse conservatism. As the gender gap in workforce participation closed, more people voted Republican.

Beyond politics, American men who lose work show increased rates of sexual harassment, sharing abusive porn, opposition to abortion, gun purchases and rejection of female politicians. Backlash is most severe in communities where unemployment has disproportionately hit men. Men who feel unfairly disadvantaged also tend to endorse hostile sexism.

This pattern repeats worldwide:

Across Europe, young men in areas with rising long-term unemployment express stronger opposition to women’s rights. (This could be a direct effect of joblessness, or difficulties in dating).

In Brazil, regions where unemployment disproportionately affected men showed stronger support for Bolsonaro. Male job loss also exacerbated domestic violence.

When Zambian mines closed and men were retrenched, their wives bore the brunt of ‘icifukushi’ (angry frustration).

British research indicates that people born in high-unemployment areas increasingly favour ideas of the male breadwinner.

In China, economic slowdown and tough marriage markets create intense pressure on men to succeed, while social media platforms like Baidu Tieba channel frustrations into misogyny.

These regional cases reveal a common pattern: when male status or core values are threatened, they often trigger organised resistance - ranging from beatings to political mobilisation. Yet the specific form and intensity of backlash varies based on local economic and cultural circumstances.

Modern Technology Amplifies Divisions

Social media can amplify tribal threats, potentially worsening antagonism. A small minority of highly active users generate the majority of online content, and their posts tend to be extreme and polarising. Algorithms turbo-charge these extremes, creating the false impression that such views are widespread. Whereas in truth, the silent majority is much more moderate.

Studies find people consistently overestimate the prevalence of opposing political extremists, while missing potential common ground. This heightened perception of threat may be stirring counter-reactions.

In Pakistan, feminist activists have mobilised as part of the Aurat march, but some slogans - like “Mera jism meri marzi” (My body, my choice) and “Apna moza khud dhundo” (Find your socks yourself) - triggered massive online backlash.

The news media intensifies these dynamics, growing markedly more negative and morally outraged. Headlines increasingly feature anger, fear, sadness and disgust.

Shocking content keeps us hooked! Experiments consistently show how we are triggered by moral outrage, find satisfaction in opponents’ misfortune and demonstrate group loyalty by attacking outsiders.

Algorithmic solutions may fall short. When Aarushi Kalra disabled social media personalisation in India, toxic content exposure dropped 27%. Yet heavy consumers simply worked harder to find inflammatory content, sharing it more frequently and switching platforms.

Our tribal psychologies seem to compound these effects. We gravitate to like-minded others, seeking news that confirms our beliefs. Cocooned in these spaces, we become immersed in group-think, rarely encountering dissent that might prompt self-reflection. Inside these bubbles, we affirm our own righteousness, often failing to recognise how far we have drifted from the mainstream.

Did MeToo worsen Divisions?

After #MeToo, Gertsberg (2024) documented an unintended consequence: junior female academics initiated 47% fewer research projects with male colleagues. While false accusations are extremely rare, viral horror stories may have magnified fears. On EJMR (a message board), male economists expressed staunch animosity about these reputational risks.

The retreat from mixed-gender collaboration was strongest at universities with both ambiguous harassment policies and higher numbers of public misconduct reports. Meanwhile, junior male academics maintained productivity by simply shifting to male-male partnerships. This illustrates how well-intentioned activism can inadvertently catalyse tensions.

All this seems to be exacerbated by modern technology. Even as we recognise the dangers of exclusionary thinking, we simultaneously choose to immerse ourselves in ideological ecosystems that reaffirm our own righteousness. Questioning conventional wisdom, breaking free from these tribal bubbles, becomes increasingly difficult. Cultural entrepreneurs can exploit this tendency by ostracising dissidents, highlighting perceived threats, and rallying defensive mobilisation.

The times have changed: splintered social media evidently amplifies backlash. Our screens exaggerate the prevalence of extremists. Cultural entrepreneurs then exploit these dynamics - highlighting perceived threats and rallying defensive mobilisation.

How can Backlash be Prevented?

Successful movements must address three challenges: they need to gradually expand cultural boundaries while building inclusive coalitions and delivering shared prosperity. Let me illustrate these principles with four examples that work across multiple dimensions.

(1) Inclusive Coalitions

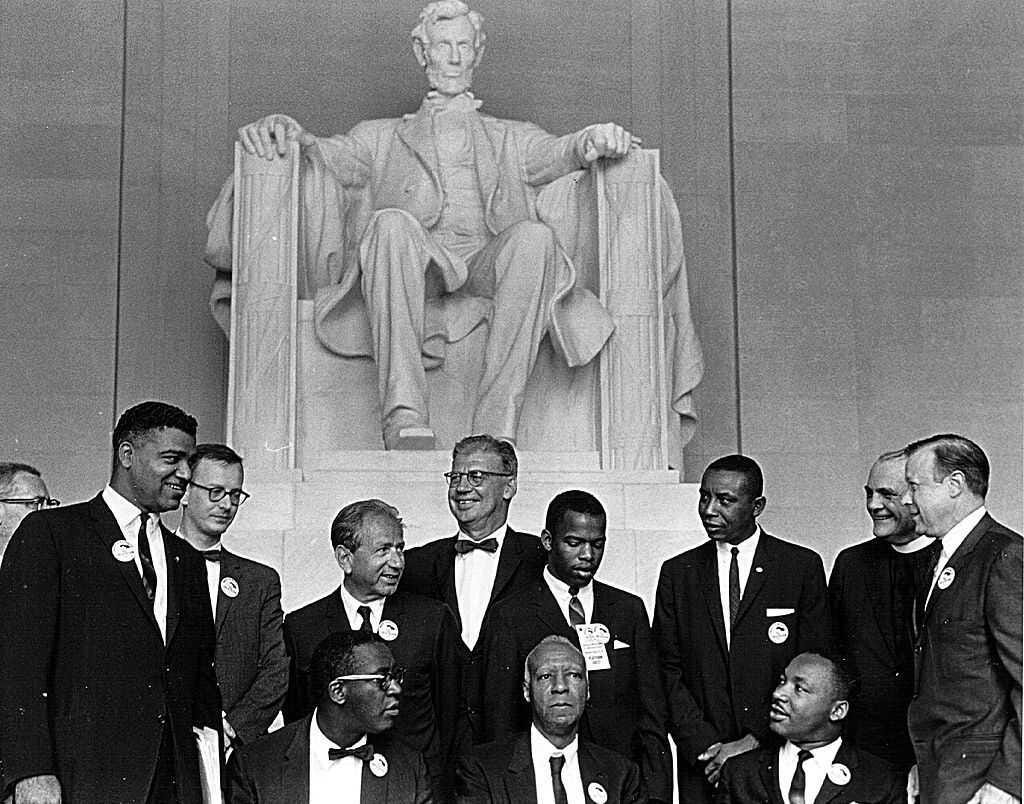

Martin Luther King Jr.'s “I Have a Dream” exemplifies how to transcend exclusionary tribalism. Rather than amplifying divisions, he invoked shared cultural symbols - from patriotic songs to biblical imagery. By layering references to both American ideals and religious values, he built an inclusive coalition that redefined civil rights as fundamentally American. This represents tribal psychology at its most effective: expanding rather than contracting the boundaries of belonging.

(2) Female Co-Workers Demonstrate Talent

During World War I, the US government faced severe labor shortages and recruited educated women as civil servants. Abhay Aneja, Silvia Farina, and Guo Xu find that this direct exposure to female competence transformed attitudes - men who worked alongside women were subsequently more likely to marry working women and have daughters who pursued careers. The effects rippled outward: cities with more female civil servants saw lasting increases in women’s employment, as women’s competence became normalised. Men come to value talented female colleagues when they see it first-hand.

This study reflects a global truth, which I have uncovered through qualitative research in nine world regions. Gender stereotypes weaken with prolonged exposure to women demonstrating equal competence in socially valued domains. That said, this may be contingent on the perception of mutual benefit rather than competition over scarce roles.

(3) Charismatic Television can Expand the Boundaries of Permissibility

While the 1970s counter-cultural movement organised street protests and marches, charismatic television was subtly stretching cultural boundaries of permissibility. Through compelling storytelling and engaging characters, shows tackled previously taboo topics with humour and warmth, signalling broader societal acceptance.

Movies, books, and music can make social change seem fun, enjoyable and exciting! As audiences invest in characters’ journeys - gasping at their setbacks, celebrating their triumphs - they may empathise with these egalitarian alternatives. We may even even aspire to be like the beautiful, successful characters we see on screen. Charming, relatable characters can help normalise what was previously unthinkable. This process shapes how we see the world and stretches what we regard as permissible.

Building on these insights, Bollywood could celebrate women securing family respect through professional achievement and remittances, showing how women’s economic contributions enhance rather than threaten male honour and family status.

(4) Supporting Disadvantaged Young Men

Any movement for equality must acknowledge that disadvantaged men are falling behind. Many struggle to acquire valued skills, face vulnerability to automation, and remain stuck in sectors where wages stagnate. This creates cascading risks - including loneliness, singledom, and childlessness. In Sweden, male fertility is much lower among those who performed poorly in cognitive tests, earnt less, or were obese.

None of this is pre-destined. Just as contraceptives and cultural celebrations enabled American women to thrive in their careers, disadvantaged young men also need support to achieve status. Progressive movements may gain broader appeal when they visibly lift all boats - including disadvantaged young men.

Advancing Equality without Triggering Backlash

How can movements advance equality without triggering revolt? Globally, we see more sustained progress towards gender equality when campaigns gradually expand the boundaries of permissibility, build inclusive coalitions, and deliver shared prosperity - particularly for those who might otherwise resist.

(1) Target locally-binding Constraints, with Careful Sequencing

Gender interventions will be most effective if they tackle locally-binding constraints, through carefully sequenced interventions.

In India, where male honour is closely tied to female seclusion, the first step might involve funding films that demonstrate widespread approval of female employment. This cultural shift, combined with job-creating economic growth, can help reduce male anxiety. As more women demonstrate their competence in valued professional roles, we would anticipate growing support for gender equality.

Careful sequencing of these steps is critical. In societies where men’s status is deeply intertwined with gender hierarchies, aggressive activism can be counterproductive and dangerous. This is particularly true in India, where the caste system’s stigma against divorce often leaves women vulnerable to enduring abuse.

In Europe and the US, organisations are often publicly shamed for gender ratios in STEM or leadership. Yet new research reveals more nuanced bottlenecks - from women’s aversion to managing teams or seeking jobs with social purpose. Tackling these precise obstacles could be more strategic. Precision tools are more effective (and more credible) than blunt force.

(2) Resonate with Core Values

Campaigns will be most successful if they appeal to broadly shared beliefs and desires. When initiatives push too far beyond what communities can accept, they risk triggering backlash. Films about girls getting jobs in Gurgaon then going ‘avara’ (wandering) and getting pregnant would likely fuel anxieties. Conservatives might even cite it as evidence of danger.

(3) Build Inclusive Coalitions

Exclusionary advocacy for a narrow group risks politicising divisions and triggering revolt. Left out, men may seek their own tribes. The most effective movements create broad-based coalitions, with collective benefits.

(4) Deliver shared economic prosperity

Leaders who fail to deliver lose legitimacy. The most effective movements combine cultural resonance with prosperity - and this includes for disadvantaged young men.

Through careful sequencing, cultural resonance, coalition-building and shared prosperity, movements for gender equality may be better able to sustain broad support.

I love this blog so much.

> While false accusations are extremely rare

Sexual violence accusations are rarely proven false. They're also rarely proven true. If someone pointed to a study that found 2% of accusations were proven true and concluded that truthful accusations are rare, is that sound reasoning? No, we also need to know how many were proven false, and how many could not be proven either way. If 96% of accusations can't be proven, and of the remaining 4%, half are proven true and half are proven false it'd be incredibly dishonest to claim this as evidence that just 2% of accusers are truthful.

Every study on false accusations I've seen have had over 50% of the sample that could not be determined true or false. The only intellectually honest answer about the rate of false accusations is that we don't know what the rate of false accusations are.