Tribalism and Modern Elections

As incumbents lose worldwide, it’s worth reflecting on a fundamental truth about human nature: we are profoundly tribal. Our collective behaviour - from political movements to social media cascades - reveals deep patterns of group psychology.

As Michael Morris details in his new book, “Tribal”, humans possess an unparalleled capacity for coordination and social learning that makes us highly attuned to our peers and heroes.

Savvy campaigners leverage this insight to build winning coalitions - speaking to shared values, demonstrating mass support, and claiming historical legitimacy.

In reviewing Morris's insights, I'll weave in perspectives from my own global history of gender and Ezra Klein's analysis of recent US elections.

The Origins of Human Coordination

The breakthrough came with Homo erectus, a million years ago - suggests Morris. Actually, this is contested. Dunbar and Wrangham suggest that coordination, organisation and language came many millennia later - with homo sapiens 300,000 years ago. Only then did early humans forge hunting groups, gathering squads, and cooking crews.

These early social bonds were cemented by collective activities that are still equally catalytic today - religious rituals, feasting, drinking, and chanting. As Robin Dunbar separately argues, such synchronous activities played a crucial role in strengthening connections. The archaeological site of Göbekli Tepe, dating to around 9500 BC, stands as testament to these ancient religious rituals.

Two Fundamental Systems

Morris identifies two psychological systems that shape human behaviour:

Peer instinct

Hero instinct

‘Peer instinct’ fundamentally distinguishes humans from other primates. Chimpanzees can invent, but rarely collaborate - such as to jointly carry heavy logs. Humans, by contrast, developed the capacity to share knowledge and forge behavioural codes. Concern for wider acceptance in turn motivates careful conformity.

As Morris puts it,

“People conform to the majority. Our brains don’t just “read minds”; they also “read the room”.

“We are less alone than other primates because we carry around our peers in our heads. We are continually reminded by our peer codes of what others in our group tend to do or think. We are kept company—and sometimes feel suffocated—by the steady stream of suggestions from our unconscious about what’s normal to think, normal to do, or normal to say in a situation”.

This insight aligns with two other great new books. Conformity and tribalism are emphasised in both Harvey Whitehouse’s “Inheritance” and Sarah Hrdy’s “Father Time”. Hrdy offers a slightly different perspective on the origins of group cooperation; she suggests that the evolution of food sharing motivated desire for group inclusion and close attention to what peers respect.

Drawing on these insights, I conceptualise cultural persistence as motivated by both desires and beliefs. Keen to secure status and social inclusion beliefs, we are highly attuned to what our peers praise or condemn, and this encourages conformity - creating a positive feedback loop.

The Hero Instinct

Now, here is a puzzle how do we learn what behaviour our community truly values? In large groups, we can’t possibly observe or ask everyone. Instead, Morris suggests that we developed a neat shortcut - we pay special attention to individuals with high-status.

An individual’s success serves as evidence that they embody traits that are widely admired. High-status individuals act as living demonstrations of what it takes to be valued, becoming beacons that illuminate the path to social esteem.

I agree entirely. The power of this prestige bias is evident throughout history. Let me give four compelling examples:

The Islamic heartland

Glorifying female sacrifice

East Asian filial piety

Trump’s miraculous survival

The Islamic heartland

Consider the 12th century map completed by Muhammad al-Idrisi, showing the south at the top and Mecca at the center of the world - a perfect encapsulation of its geopolitical standing for Muslims, which in turn motivated wider emulation.

This psychological system transformed early human societies, argues Morris. Instead of members simply conforming to group behaviour, they began actively seeking ways to contribute that would earn community recognition. This drive helped spread innovations like new hunting techniques and tool-making skills. More importantly, it motivated people to sometimes set aside their immediate self-interest in favour of actions that would enhance their standing in the group, and become HEROES!

Glorifying female sacrifice

While Morris focuses primarily on masculine pathways to status, like noble warriors, there are important female parallels - self-sacrificial wives and daughters-in-law glorified in songs, folklore and literature. These stories, handed down over generations, celebrate great heroines who put others first.

East Asian Filial Piety

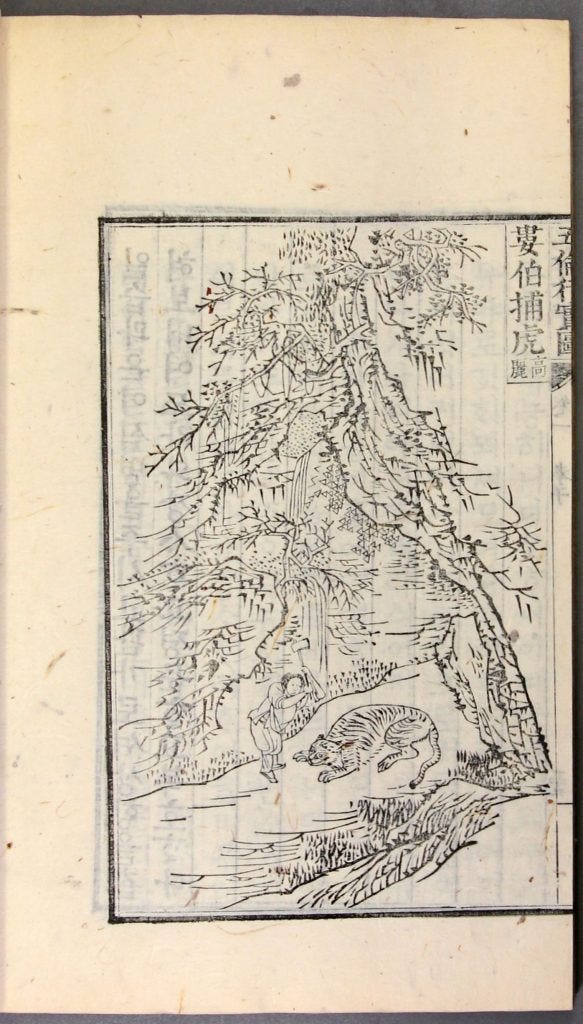

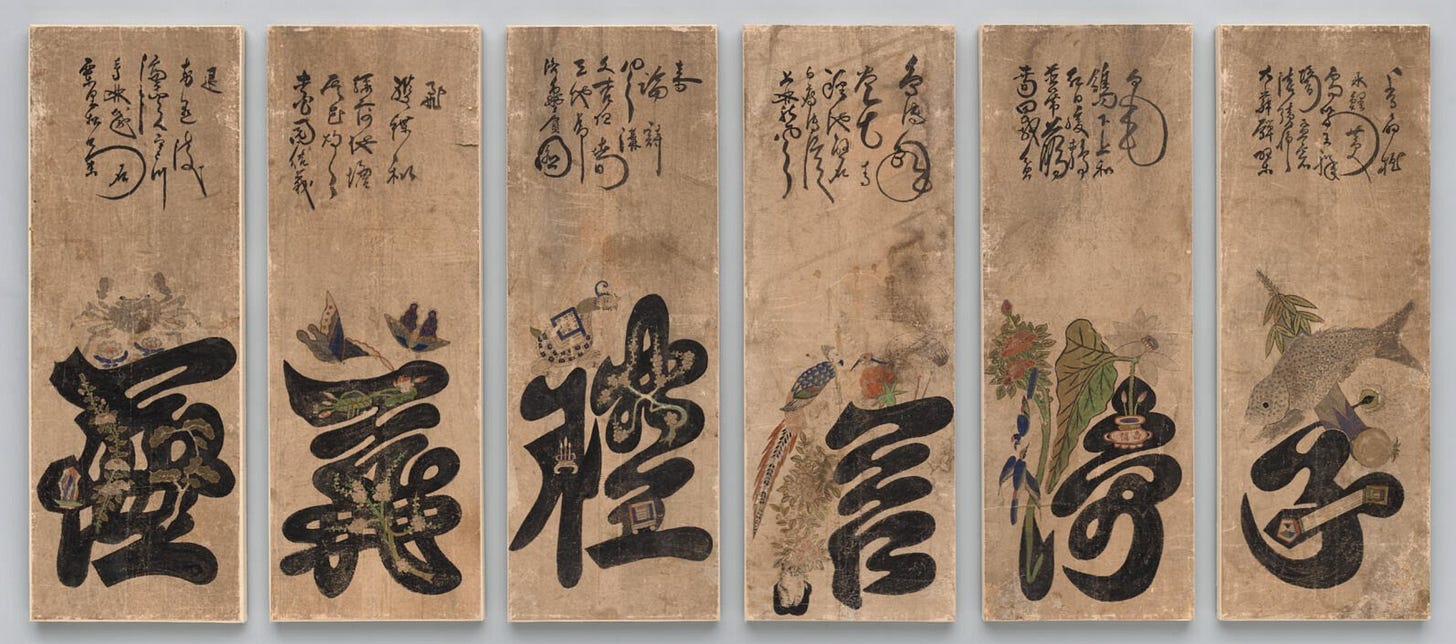

Let me give another example of filial piety - eulogised in East Asian folklore and paintings. “Nu-baek Catches the Tiger” is about a 15 year old boy who defeats the tiger that ate his father, retrieves his father’s body, and conducts a proper burial.

This 19th century Korean panel likewise displays cardinal virtues: brotherly love, trust, propriety, righteousness, and integrity. Two are missing: loyalty and sensitivity. These were originally in Chinese, but adopted in Korea. The stringed musical instrument (a zither) represents the classic story of Shun, who always obeyed his blind father and abusive family. Loyalty meant he was chosen as emperor and given a zither. The fish represents a filial son who lay on a frozen river, caught fresh carp for his unkind stepmother and earnt her respect.

By teaching these stories of celebrated heroes, East Asian families taught their children the pathways to status and social inclusion.

Trump’s miraculous survival

We will never know how much support Trump gained by surviving a shooting, raising his fist, and claiming divine protection.

Morris argues that these two instincts - to emulate peers and heroes - continue to shape modern behaviour. It explains why we instinctively emulate successful individuals, why we care so deeply about our reputation, and why we sometimes feel compelled to be heroic even at personal cost.

Michael Morris, like Harvey Whitehouse, believes that these tribal psychologies are deeply rooted, but nonetheless malleable. They can be manipulated to build reform coalitions.

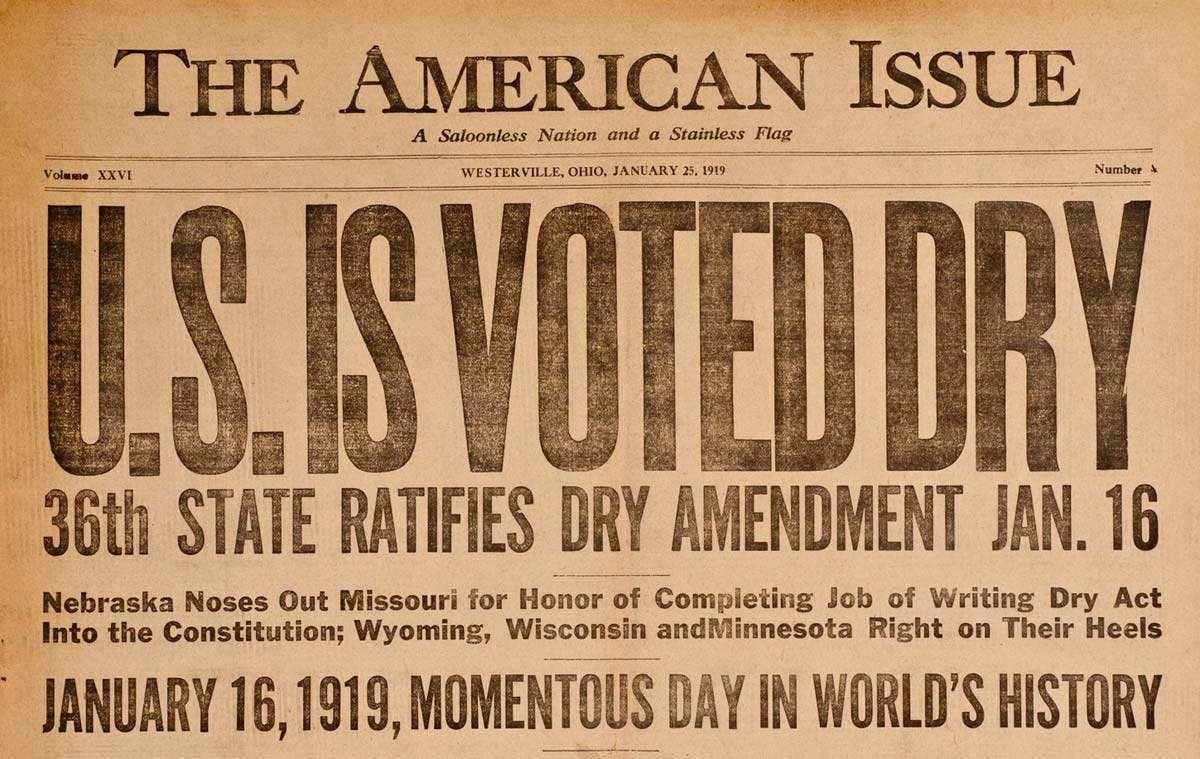

The US Temperance Movement

The US Temperance Movement provides a fascinating case study in how activists can leverage our tribal instincts. Campaigners artfully created the impression that huge swathes of Americans vociferously opposed drinking. They organised conspicuous pledge events in public squares, featuring rousing speeches and dramatic oath-taking ceremonies. Moreover, they flooded newspapers with press releases touting the swelling ranks of teetotallers - one million pledges, then two million - while strategically omitting mention of the other ten million Americans who remained silent. Campaigners bigged up their agenda, with a deluge ‘scientific temperance instruction’.

Morris adds,

“Regardless of its medical soundness, the sheer prevalence of this literature sent its own message: the abstinence attitude appeared to be everywhere”

The movement's most innovative tactic came in 1913, when the Anti-Saloon League revolutionised political activism by inventing ‘pressure politics’. As states prepared to vote on dry laws, they orchestrated thirteen thousand members to write to their representatives demanding restrictions. To legislators who had never seen such enormous volumes of correspondence, it appeared the entire business community was demanding action!

States went dry! By 1917, nationwide prohibition was proposed as the Eighteenth Amendment, ratified two years later by thirty-seven states.

Yet this apparent triumph of public opinion was only superficial. When the Literary Digest polled its readers on Prohibition in 1922, they discovered something surprising: most respondents actually preferred alcohol sales. There was an enormous gulf between activists’ rhetoric and private opinion. The dry faction had made themselves highly visible through pledge events, revival meetings, and letter-writing campaigns. And that generated a false impression of majoritarian support, which generated conformism, by playing on our peer instincts.

Biden’s Demise

Morris says that ‘peer codes are sensitive to prevalence signals: information about what groupmates do, or think or say’. Now, let me highlight a contemporary parallel.

Earlier this year, President Biden often acted rather oddly, showing signs of old age, but party elites remained silent. This fostered a culture of self-censorship. Barely anyone spoke out, save Ezra Klein who was subsequently hammered.

Only after the debate with Trump, when the issues became overwhelmingly visible and prestigious commentators highlighted concerns, did others start to come out.

Similarly, after the Democrats’ recent defeat, you may have noticed a remarkable swing in discourse. Progressive commentators and media outlets like the New York Times are suddenly expressing internal critiques. Once this critique became legitimised, it appears to have spread rapidly in an extremely fast cascade.

Television!

The power of social influence extends beyond politics into mass media, as demonstrated by a fascinating discovery in Mexican television. When producer Miguel Sabido noticed viewers physically attacking an actor playing a villainous character in a grocery store, he realised something profound. Viewers become so deeply immersed in television dramas that it becomes an emotionally salient reality. He developed what became known as the Sabido Method, using carefully crafted characters - positive role models and negative examples - to promote social change.

The results were remarkable. His literacy-focused show ‘Ven Conmigo’ drove a million adults to enrol in school. ‘Acompáñame’ increased contraceptive sales by 23% and family planning appointments by 33%. These techniques were later adapted globally. In Tanzania, the radio drama ‘Twende na Wakati’ (‘Let's Go with the Times’) addressed the AIDS crisis. 82% of listeners reported adopting safe-sex practices as a result.

Right now, these exact same dynamics are playing out in Saudi Arabia.

All this plays on our deeply-rooted peer and hero instincts.

Parallels in the Muslim World

Simply broadcasting alternative lifestyles isn’t enough. Through my globally comparative research, I realise that effective cultural change requires clear signals that these alternatives are being adopted by each community’s peers and prestigious heroes. This is why 20th century innovations in communications led not to Americanisation, but also to Arabisation, with young men in Luton and the wider Muslim world donning Arab thobes. They emulate the Islamic heartland, which now has additional sources of prestige: the glitter and glamour of oil wealth.

Today in Saudi Arabia, Mohammed Bin Salman is on a new tack. He seeks to culturally liberalise and is marshalling state-owned media streaming platform Shahid to normalise women in the public sphere.

Crucially, it’s about convincingly signalling that these changes are embraced by respected peers and cultural heroes. The Saudi state appears to understand this tribal psychology, carefully cultivating images of Saudi royalty embracing liberalism. By showcasing local heroes adopting these changes while maintaining their Saudi identity, they help make cultural evolution feel both authentic and prestigious.

Tribalism Goes Online

This insight about prestige and peer influence takes on new dimensions in our digital age through what Morris calls ‘epistemic tribalism’, where tribal conformity takes precedence over truth-seeking. While the splintering of our media landscape has accelerated these divisions, Morris doesn’t blame the algorithms. Rather, as a tribal species, we instinctively surround ourselves with like-minded others. A more rational species might use increased media choice to challenge and refine their understanding. Instead, we gravitate toward news with a congenial slant, creating ‘partisan bubbles’.

Cocooned in ideological ecosystems of like-minded others, we become immersed in networks of conformism. As individuals seek status and inclusion within their networks, they pay close attention to what is widely esteemed and learn to quietly conform. Morris does not say this, but vocal activists can of course guide group think by vehemently expressing their beliefs, ostracising dissidents and thereby encouraging wider conformism.

The Cultural Connotations of Language

While media can shape behaviour through storytelling, sometimes changing deeply rooted cultural patterns requires an even more fundamental shift. Morris gives the striking example of Korean Air. After recognising that hierarchal norms inhibited open communication in the cockpit, they shifted to talking in English. Once pilots were speaking and thinking differently, their safety record dramatically improved!

Inventing Tradition

As I have previously argued, each society has a unique cultural inheritance that provides a spectrum of permissibility. Within every society worldwide, progressives and conservatives mobilise at opposite ends of this spectrum, each seeking to gain institutional dominance and broader ideological influence. When either side pushes too far beyond what the median citizen can accept, their efforts can appear threatening and trigger backlash.

How can such backlash be prevented?

My earlier work identified several paths to successful reform: building broad-based coalitions, using charismatic television to normalise change, and delivering economic success that generates performance legitimacy.

Morris offers an alternative perspective. He demonstrates how leaders have legitimised their authority amid transition by strategically invoking - and sometimes inventing - tradition.

The British monarchy

After the disruption of World War I forced the royal family to abandon their German name for ‘Windsor’, and following Edward VIII's destabilising abdication in 1936, the monarchy doubled down on ceremonial displays of historical continuity. For the first time in 500 years, they began holding royal weddings in Westminster Abbeys, creating new rituals that signalled ancient authority!

The changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, which attracts tourists as a quintessential display of old England, similarly emerged as a response to industrialisation. As rapid social change created nostalgia, the monarchy heightened its ceremonial displays to provide stability and reassurance.

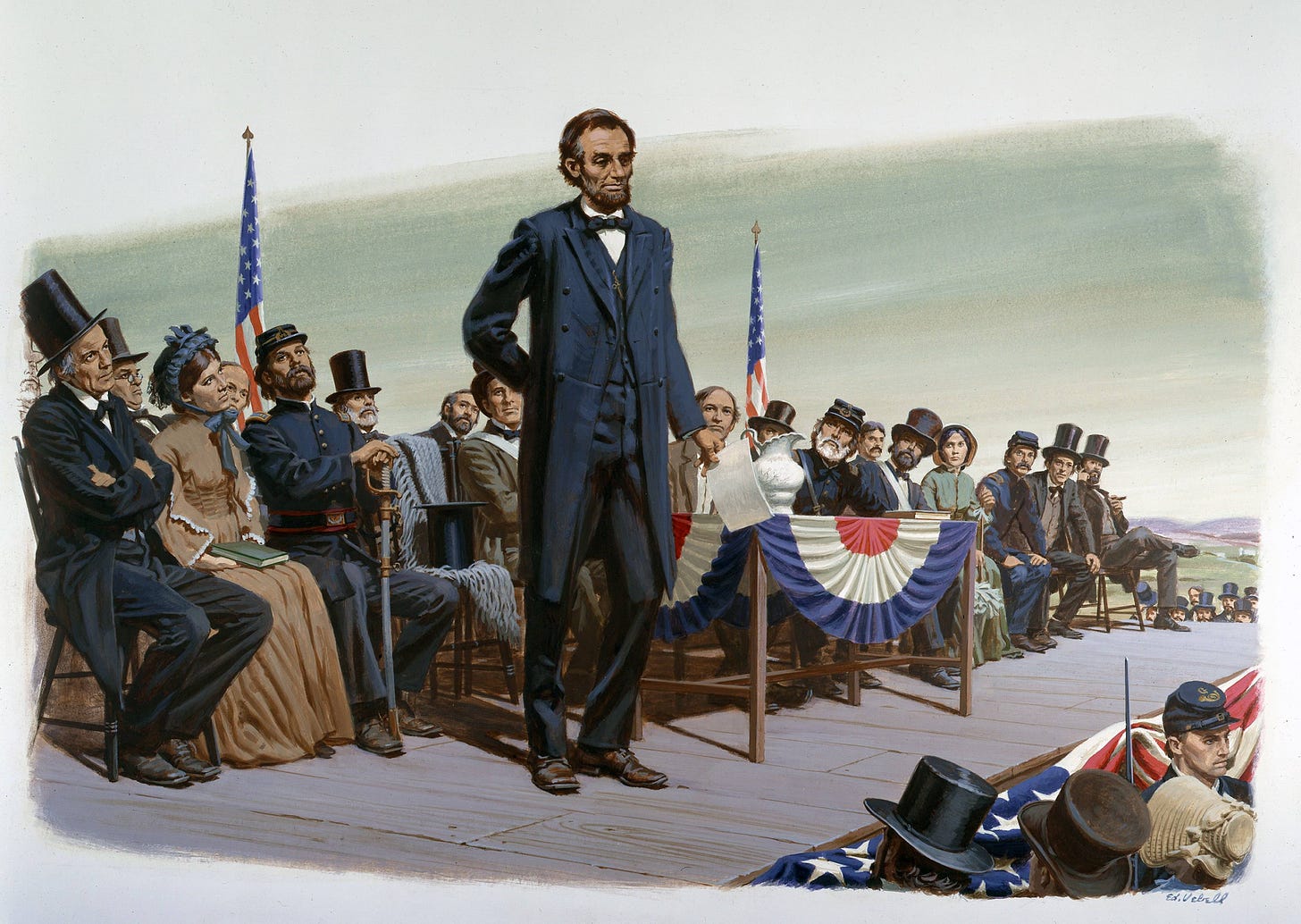

President Lincoln

When Lincoln took office with less than 40% of the popular vote, he faced a similar crisis of legitimacy. Just like the British monarchy, he deliberately positioned himself within a grand historical narrative, connecting his presidency to the traditions of America’s earliest settlers. By invoking a shared heritage that predated current divisions, Lincoln created space for his unifying agenda.

Morris argues this pattern - using real or invented traditions to manage change - appears across cultures and institutions. Corporate leaders invoke company heritage when introducing new initiatives. Religious reformers ground innovations in ancient texts. Political movements wrap new ideas in the language of traditional values. The counterintuitive lesson is that successful change often requires not just a compelling vision for the future but a rousing connection with the past! Morris suggests that when people see their leader as connected to revered historical traditions, they’re more likely to accept novelty as perfectly consistent with their group's enduring values rather than as threatening departures.

“Make America Great Again”

Let me offer some more examples, omitted by Morris, and starting with the most obvious. By repeatedly wearing his cap and repeating the slogan, “Make America Great Again”, Trump explicitly appealed to American pride.

‘Scandinavian values’

When Swedish Enlightenment thinkers, Social Democrats and Feminists sought reform, they continually portrayed their ideals are in-keeping with medieval ideals of freedom and equality! Proud histories of the 13th century were thus called upon to champion a particular vision of Swedish modernity! Only state intervention could secure their cherished values of independence.

Mughals claimed cultural continuity with Mongols

I can give more examples of how art was used to invent tradition - claiming that ancestors and goddesses always practised veiling.

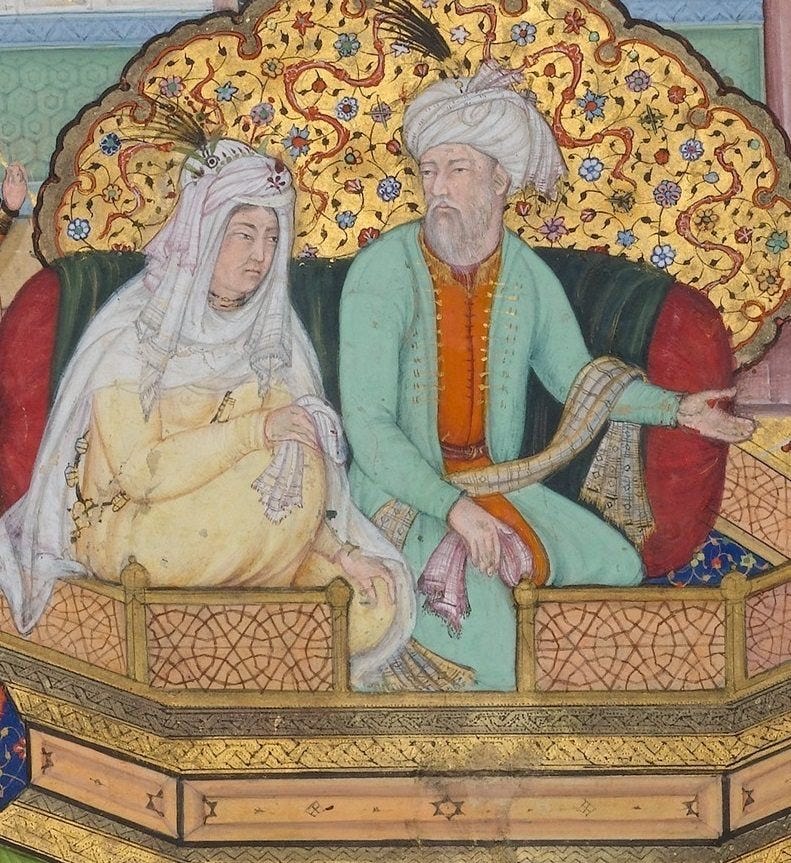

Akbar, the third Mughal Emperor of India (1542-1605), claimed descent from Genghis Khan and commissioned an illustrated copy of the Chingiz-nama (written in Persian by a Jewish convert to Islam). This illustration below shows the ruler Tumanba Khan, an ancestor of Genghis Khan, with his wife and nine sons.

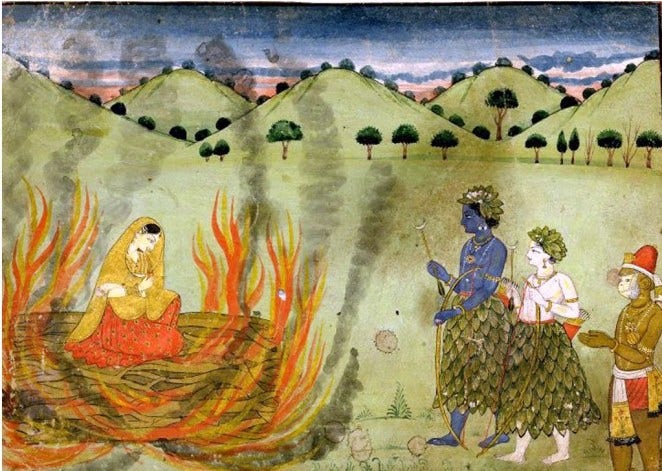

But this painting is totally inaccurate! It invents tradition. They impose Mughal ideals of veiling onto Mongols (who had a totally different morality). The exact same trend is shown in Mughal paintings of Hindu mythology. Both were claiming that their practices were shared by their founding fathers.

Building Bridges

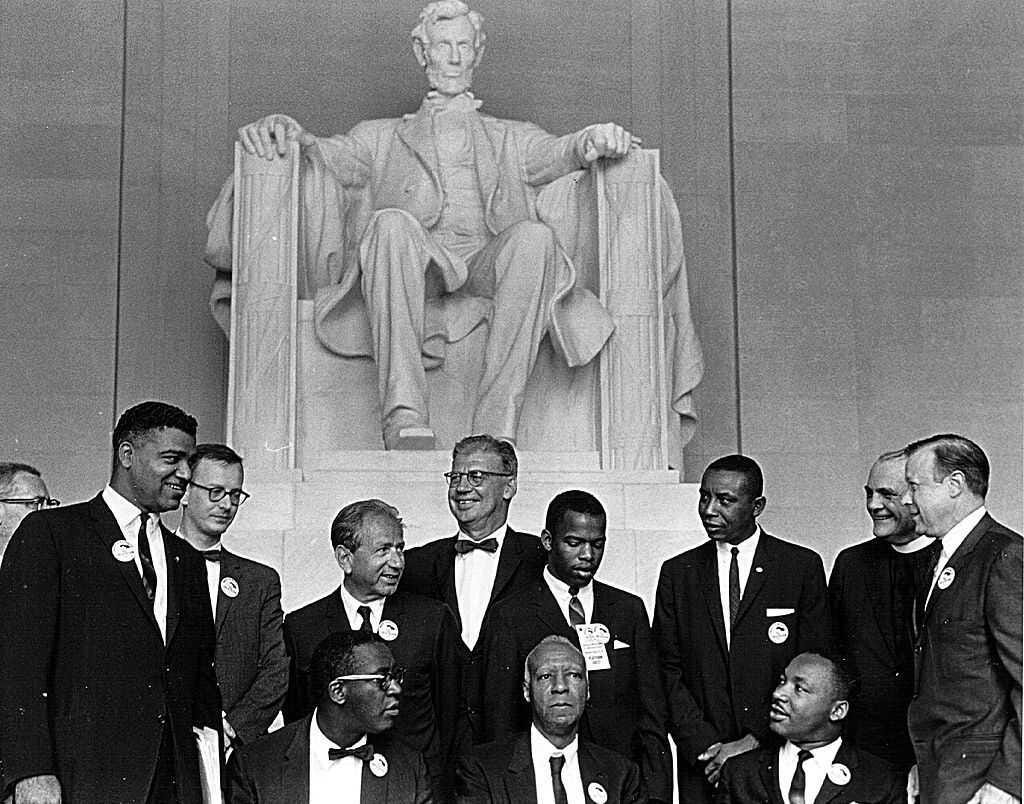

Martin Luther King Jr. famously demonstrated this principle with “I have a dream”. Rather than speaking only to his core supporters, King deliberately wove together shared symbols and ideals that could unite diverse audiences. He referenced the country's founding principles, invoking the ‘American dream’ and the creed that ‘all men are created equal’. He layered in allusions to patriotic songs about ‘sweet land of liberty’ alongside biblical psalms and parables about equality before God. The speech culminated in a powerful fusion of religious and secular imagery, calling for all of ‘God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics’ to join together in freedom.

This was was tribal psychology at its most effective. he American flag and references to Lincoln activated his audience's attachment to political ideals of equal opportunity. Religious imagery called forth moral ideals about human dignity. By weaving these different symbolic threads together, King helped diverse audiences see civil rights as an expression of their own deeply held values rather than a threat to them.

Just today, Ezra Klein appealed to Democrats to rebuild connections with voters who currently perceive them as hostile:

Effective Movements: Cultural Resonance Plus Results

Tribal psychology is neither inherently divisive nor unifying - it's a fundamental aspect of human nature that can be channeled in either direction. Successful political movements skillfully harness our peer and hero instincts.

From the British monarchy's reinvention to Trump's “Make America Great Again”, leaders gain popularity by championing widely-shared values. Alternative movements - appearing out of touch and threatening - may trigger backlash.

Morris's insights point to three critical elements for successful reform:

Shared cultural narratives and traditions

Visible support from respected, successful individuals

Inclusive coalitions

But Morris misses one crucial factor: Economics. Leaders who fail to deliver prosperity lose legitimacy - just look at the downfall of Arab modernisers, widely blamed on military defeat and secular stagnation. The most effective movements combine cultural resonance with tangible results.

When I wrote about this 19 years ago in my book Us and Them (U Chicago Press, still in print!), the first edition subtitle was "Understanding Your Tribal Mind."

However, I now try to avoid using the word "tribal." I think it invites people to think of themselves as sophisticated victims of some supposedly atavistic and primordial trait. As if our political parties and nations were higher ideals that fall back into this less desirable state under pressure.

After more experience with people who are members of actual tribes -- that is, people who think and feel tribal identities the way I sense national, religious and ethnic identities -- I see that "tribal" experience is no more or less primitive than other forms of categorization.

As a filmmaker, I would urge caution around the use of mass media as a tool for social transformation. While it can be highly effective, as the Mexican and Tanzanian examples show, it can also lead to audience fragmentation if the message is poorly crafted or too far outside the current values of a society.

For example, in the Anglosphere lots of people have stopped watching Hollywood productions (especially 'preachy' TV shows) over the last decade. Based on the comments I see online and amongst my peers in New Zealand, those who aren't watching explicitly mention poor writing/acting, 'the message', or 'the woke agenda' as their reason for tuning out and turning to independent productions instead. In this case, it would seem that the message embedded in these mass media productions is poorly crafted and fundamentally not resonating with the consumers who are expected to pay for it.

This can cause a ripple effect where audiences that are supposed to be swayed towards a message will rebel against it. We can see this in the current trans debate in America, where hostility towards trans issues is increasing despite the messaging in establishment media products. One example of this is the analysis suggesting that the "Kamala is for they/them, Trump is for you" campaign helped to swing the recent election.

That being said, I thought your recent article about using Bollywood to promote the education and employment of young women from rural India would likely be an effective use of mass media messaging. This is partly because Bollywood movies are an event that the whole family goes to see, even if they might leave the cinema during segments that don't interest them, but also because there is a big societal shift happening amongst the burgeoning middle class of India that a well crafted message could take advantage of.