Glorifying Sacrifice

Female sacrifice has been glorified in India and China for two thousand years. Why does it persist and how has it changed?

Ruling elites marshalled large armies by lavishing praise upon militias as ‘brave, noble and heroic’. English men fought for ‘King and Country’; 3000 kamikaze pilots intentionally crashed into enemy warships; jihadists are likewise celebrated as martyrs. Military bravado was so highly revered that men signed up for the forlorn hope.

Patriarchal cultures, meanwhile, have extolled female sacrifice for male honour. At the extreme, this Rajput widows were praised for committing sati - burning in the flames of their husband’s funeral pyre marked true devotion. Chinese literature exalted women who preserved their chastity through self-mutilation. While oppression is sometimes coerced, it may also be willingly embraced: women step into the flames.

Collectivist cultures teach children to put family first and respect their elders. “The arrow runs from the bottom to the top, not the other way around. If you go the wrong way, you are a rebel!” - complained my Chinese Malaysian friend about Confucianism.

‘Good girls’ comply, while disobedience brings guilt and shame. If people truly believe that elders should be obeyed, then selfish pursuits make them feel psychologically terrible. If ‘loving mothers’ cook and care for their children, then an absentee careerist feels her stomach knot with painful anguish. Culturally tight societies also enforce collective punishment: if a young woman is disreputable, her entire family may be outcaste and ostracised. Everyone else quickly learns to conform.

In patrilocal societies, both men and women are taught to obey elders and prioritise the collective. Male sacrifice is real, but the focus is on production. Men work hard - but simultaneously amass resources, skills, networks and status. Girls, by contrast, are more closely confined, move to live with their in-laws, and thereafter remain junior outsiders. Their sacrifices are to be abstemious and protect their marriages at all costs, even violence. Why? Because marriage is the lynchpin of intensive kinship.

So let’s explore praise for female sacrifice, as true love.

India

It is impossible to specify what gender relations were like thousands of years ago. Genetics, iconography, inscriptions and religious proscriptions provide useful clues, but there was likely much heterogeneity - by religion, wealth, region, tribe and jati.

Genetic sequencing reveals that India’s caste system has existed for several millennia. Endogamy could have only been maintained by socialising girls to obey their in-laws, marry young and stay there til death - enduring any violence. Impropriety was punished by assemblies of older men (caste panchayats), who expelled entire families because of one daughter’s misdeeds. The caste system depended on female purity. Girls improved their marriage prospects by signalling virginity. Strict surveillance enhanced family status. Everyone else learnt to conform and teach their daughters to stay quiet: ‘chup’.

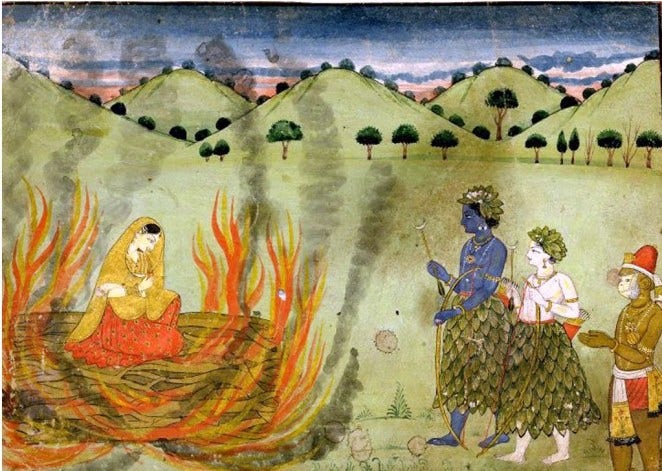

The Hindu Goddess Sita epitomises sacrifice. In the Ramayana (written in the first millennium BC), Sita was taken captive to Lanka. Despite Ravana’s multiple offers of marriage, she remained loyal to her husband. Rama mobilises an army to secure her return, but actually treats her coldly and publicly doubts her purity. To prove her fidelity, Sita enters a burning fire. Years later, her chastity is questioned once again, and Rama succumbs to public pressure. Sita was distraught; Mother Earth opens up. She remains the ultimate model of female devotion - revered in Hindu mythology for over two thousand years.

Female subordination was prescribed by the Laws of Manu (100 CE). The Bhagavad Gita 9.32 describes girls and sudras (lowest caste) as lower births, born of sinful parentage, barred from Hindu moksa (spiritual liberation).

Widow chastity became normative by 1000 CE. Even child widows were supposed to remain eternally chaste. She was also supposed to be abstemious, give up good food, and fast - so as to ensure her dead husband’s peace of mind. Considering that girls usually married at or even before puberty, to older men, most women would have endured extreme hardships. To me, this indicates women’s low status and inability to challenge patriarchal smṛtikāras (law makers) who prioritised chastity.

Sati was highly revered in Early Medieval India. Family performances were sometimes hyped up by the state to motivate wider practices of female devotion. The term ‘sati’ even became synonymous with ‘virtuous woman’. Inscriptions in Mysore, Central Provinces, Banaras, West Bengal, Western Gangas, Bharatpur and Jaipur all praise ‘living satis’. Dedicated to their lords, ‘living satis’ epitomised purity and perfection.

Hundreds of sati peethas (shrines) and devli (memorial stones), dating back to the 8th century have been found across Rajasthan. Also in the South, inscriptions exalt sati:

All (her relatives) united said: ‘Do not (die)!; desist!;‘ (but) Dekabbe said: ‘Speak not. But go!; I will not desist;’ and respectively giving land, gold, clothes, cows and money as a present, she piously put the palms of (her) hands together (in obeisance) to the god of gods, entered the blazing flames, and went with glory to the world of gods, so that the whole earth will be pleased (with her) and continually praise her (Mysore, 1057 CE).

North India seems to have been more patriarchal, in general. Hindu smrti commentators (idealising wifely devotion) exercised great authority, but were resisted in the south. Jainism (patronised by dynasties in the south) permitted women’s spiritual growth. The Bhakti movement also encouraged women of all classes to preach. Southern territories were sometimes ruled in collaboration with female kin. This geographical diversity may partly reflect inheritance: Ancestral North Indians have more Indo-European ancestry.

Female sacrifice is still idealised

In 21st Century India, girls are taught that female sacrifice is morally good. Rarely invited to reflect upon their own desires, daughters learn to put others first. Compliance secures both family love and wider social approval.

As Deepa Narayan explains in her brilliant book “Chup”:

“When suffering is made morally superior and is no longer a source of societal concern, it makes no sense to seek escape… To be good is to suffer. To suffer is to be good. This lie keeps women confused, trapped, powerless.. despite education, jobs and wealth”.

Qualitative research across India points to these internalised ideologies:

“A woman is required to be everything for her husband – be a sister, mom, an apsara or whatever, a good housewife; be there for him for everything, be everything for him. The only focus is his happiness” (Sunetra (27) - who came close to killing herself after prolonged abuse, quoted in Narayan 2018)

“Women are brought up to think that they should serve others - be it her husband, her elders, her children or her household members. Not herself. Women are trained not to care for themselves” (Medha, quoted in Lamb 2022)

Hundreds still gather outside the home of Rup Kanwar, who committed sati in 1987. They come to worship:

“Their mannat (prayer) gets fulfilled, why else would busloads of people come all the way?” - Prem Kanwar (65 years old, who said she felt proud of ‘sati mata’.

Female deference manifests in acceptance of arranged marriage, widespread endorsement of male violence, high reports of male violence, yet ultra low divorce. Grooms in Karnataka are so confident in their wives’ loyalty that they violently beat their new brides, expecting them to beg their parents for a larger dowry.

In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Orissa, most women say that men eat first. Meanwhile, 57% of Indian women are anaemic - double that of men.

Male sacrifice is real; Indian men work hard for their families. But such productive activities enable men to amass resources, skills, social networks and ultimately status. Whereas for Indian women, sacrifice is a low-status trap.

China

China is a perfect comparison because it was also patrilineal and patrilocal. Sons were celebrated as scions of the family line, while women were ideally chaste and submissive. Sacrifice continues to be extolled but, due to rapid economic economic growth, it is far less gendered.

Widow chastity was exalted in Liu Xiang’s (79-8 BCE) book “Biographies of Exemplary Women”. Wives should be eternal faithful. This galvanised a literary genre in which male authors took it upon themselves to define female virtues.

“To transgress a rule of righteousness in order to save one’s life is not as good as to keep the rule of righteousness and to die in doing so” - the widow Bo Ji told bystanders why she preferred to be incinerated alive than leave a burning building unescorted, exposed to non-related men.

Beautiful Gaoxing of Liang was widowed in her youth and then attracted many suitors (including the ruler of Liang). To preserve her chastity and repel all suitors, Gaoxing cut off her nose. She was praised as righteous.

Chinese literature (overwhelmingly authored by men) increasingly emphasised female sacrifice for male honour.

78% of stories about chaste women in “Ming History” (the major account of this dynasty) ended with the heroine’s death. Female suicide was heralded as virtuous.

Tang histories likewise eulogise female devotion. Ms Wang drank poison rather than betray her family. The Dou sisters jumped off a cliff to avoid rape. 12 of the 53 biographies of ‘exemplary women’ in the two Tang official histories involved self-mutilation. Others end in death.

Before the Song dynasty, these ideals may have been confined to a tiny minority - since literature was prohibitively expensive. In the 3rd century CE, Ge Hong grumbled that men and women associated freely. Records from the time attest to women and men inter- mingling: visiting temples, participating in religious ceremonies. Patriarchal Confucianism was not the only game in town. There was a rich diversity of thought. Daoism permitted women to achieved spiritual authority and perfection.

The advent of printing and meritocratic civil service exams (based on Confucianism) encouraged cultural homogenisation. North Chinese mothers began to break their daughters’ feet, to signal chastity, beauty and secure good marriages.

All the available evidence suggests these norms of female subordination and sacrifice continued well into the 20th century.

What changed?

Rapid economic growth

East Asia industrialised rapidly and families were willing to exploit female labour in response to new economic opportunities. East Asia witnessed the classic case of balanced growth: rapid productivity growth in agriculture, which released labour into other sectors; combined with rapid growth in manufacturing and services, which absorbed the rural labour.

The demand for labour in industry and services was so strong that the opportunity cost of keeping your daughter at home increased for entire villages. When all families sent their daughters to factories, fears of disapproval dissipated. Female employment became widely accepted.

Industrialisation creates the social context in which women can pursue their own emancipation. Chinese daughters gained ‘face’ (respect and social standing) by remitting earnings, supporting their families, and showing filial piety just like sons.

Sacrificial ideals persist, but Chinese women are increasingly showing this with money. They are buying status. With more female out-migration and remittances, Chinese villagers increasingly value their daughters. Urban women express their newfound pride, status, exemptions from care work, and voice in family decision-making.

When my parents have some problems, they all turn to me and ask for my opinion

- Nan, shop assistant in Beijing since 1998 ( Zhang 2014).

By migrating to cities, women made friends, bemoaned unfair practices, and discovered more egalitarian alternatives. Emboldened by peer support, women came to expect and demand better - in dating, domesticity, and industrial relations alike. Mingling freely in cities, young adults increasingly dated before marriage, chose their own partners, then established their own households. They liberated themselves from parental control. Middle class women want their husbands to treat them as equals.

Together with other boys and girls from my school, I was taught.. [that] we must study hard and enter a good university, so that we can become successful in our work, therefore ‘giving back’ to our parents and zu guo (motherland,祖 国 ).

Fierce competitions that must be won through individual efforts and deliberate self-cultivation were instilled as the norm from our earliest school years, as this was the only way for one to deserve a bright future.

Gender was not significant in my imagination of the future at that time. It seemed that everything would just happen ‘naturally’ as we grew up.. I never doubted that I would have a career.. None of us had a clue about how our lives might differ from those of our male peers’ (quoted in Xie 2021).

China is no feminist utopia, however. Patriarchal authoritarianism sustains impunity for male violence. The CCP shames singles who do not sacrifice their careers for marriage and family - tarring them as ‘leftover women’. Economic slowdown also threatens earlier gains. Employment discrimination is absolutely brazen.

My point here is not to praise China, but to highlight the power of economic growth.

Job-creating economic growth dismantles gendered sacrifice

Collectivist cultures preach sacrifice. Dissent brings emotional anguish, social disapproval and even ostracism. In patrilocal China and India, filial devotion was distinctly gendered. Men’s labours actually advanced their resources, networks and status. Whereas women were expected to endure everything - even psychological and physical abuse. Preserving marriage was absolutely imperative - since it was the foundation of intensive kinship.

Today, many Indian and Chinese men and women care deeply about their families and consider collective interests. However, China’s rapid economic growth has eroded gender differences. By seizing economic opportunities, Chinese women can show filial piety, while simultaneously gaining wider solidarity and status.

That is perhaps the most important lesson from my global history of gender.

Another fascinating post Alice, thank you. My paternal grandparents were married when my grandmother was just 11 years old, ten years younger than my grandfather. She remained in her parent's home till she was 14, which is Juliet's age in Act 1 of Shakespeare's play. She learned to read in her mid forties, when a tutor was hired for her youngest daughter. We did not share a language in common, but we could communicate a bit when she spoke Punjabi and I replied in Hindi. The only books I ever remember her reading were scripture. Her first child was stillborn, after which she had five live births. The youngest (mentioned above) went on to win India's third highest civilian honor, the Padma Bhushan, for her work on behalf of the developmentally disabled. Her own daughter, my first cousin, was born with cerebral palsy and my aunt has spent the better part of the last forty years building and running schools and research centers for people with severe intellectual disabilities. This is her:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shayama_Chona

Sorry for oversharing, but your post made vivid for me the kind of life she must have led.

My grandmother was in her early teens when she was married. Granddad was just few months older than her. She went on to have 10 kids. She taught herself to read and write while her kids got educated.

I am the elder of 2 siblings. When my sister was born, she insisted that her son, my dad, have a vasectomy. She didnt want her daughter-in-law to go through what she went through. This enabled my mother to have a career as a teacher.