Automation, Ageing & Men's Loss of Status

Young men are faltering in the grand game of status. It’s always hard to identify causal mechanisms, but let me share the latest empirical literature…

The least educated men have struggled to move out of jobs vulnerable to automation. Relative to women, they’re also less likely to finish university.

Even if men graduate, they’re not becoming Don Draper (complete with corner office and doting secretary). Demographic ageing means that older workers are keeping their jobs, potentially blocking young men’s promotion to manager.

Compared to previous generations, young men are now less likely to enjoy hierarchical status and seniority over women. This levelling holds for both the least and the most educated men.

These two sets of empirical literature are usually considered separately: social scientists either focus on the least educated men falling behind, or gender disparities among graduates. However, if we put it all together, we see that Gen Z is experiencing an overarching trend of status convergence.

Men are Less likely to Go to College

Boys are disproportionately struggling.

In the UK, boys are almost twice as likely to be suspended, and they’re less likely to achieve the expected standard in English reading and writing (56% compared with 63% of girls).

While boys historically performed better in maths, these gaps are closing – 72% of girls and 73% of boys met the expected standard for maths.

As of 2020, British boys now have a higher NEET rate: 12.8% of boys and 11.8% of girls are Not in Education, Employment or Training.

If university admissions are determined by meritocratic performance, then women will disproportionately achieve higher qualifications.

N.B. Not all universities are meritocratic. Recall that Toyko Medical University has been altering women’s test scores to keep them out.

Across many economies, men are less likely to complete college.

Men’s educational struggles interact with shifts in the labour market.

The Decline of Manufacturing

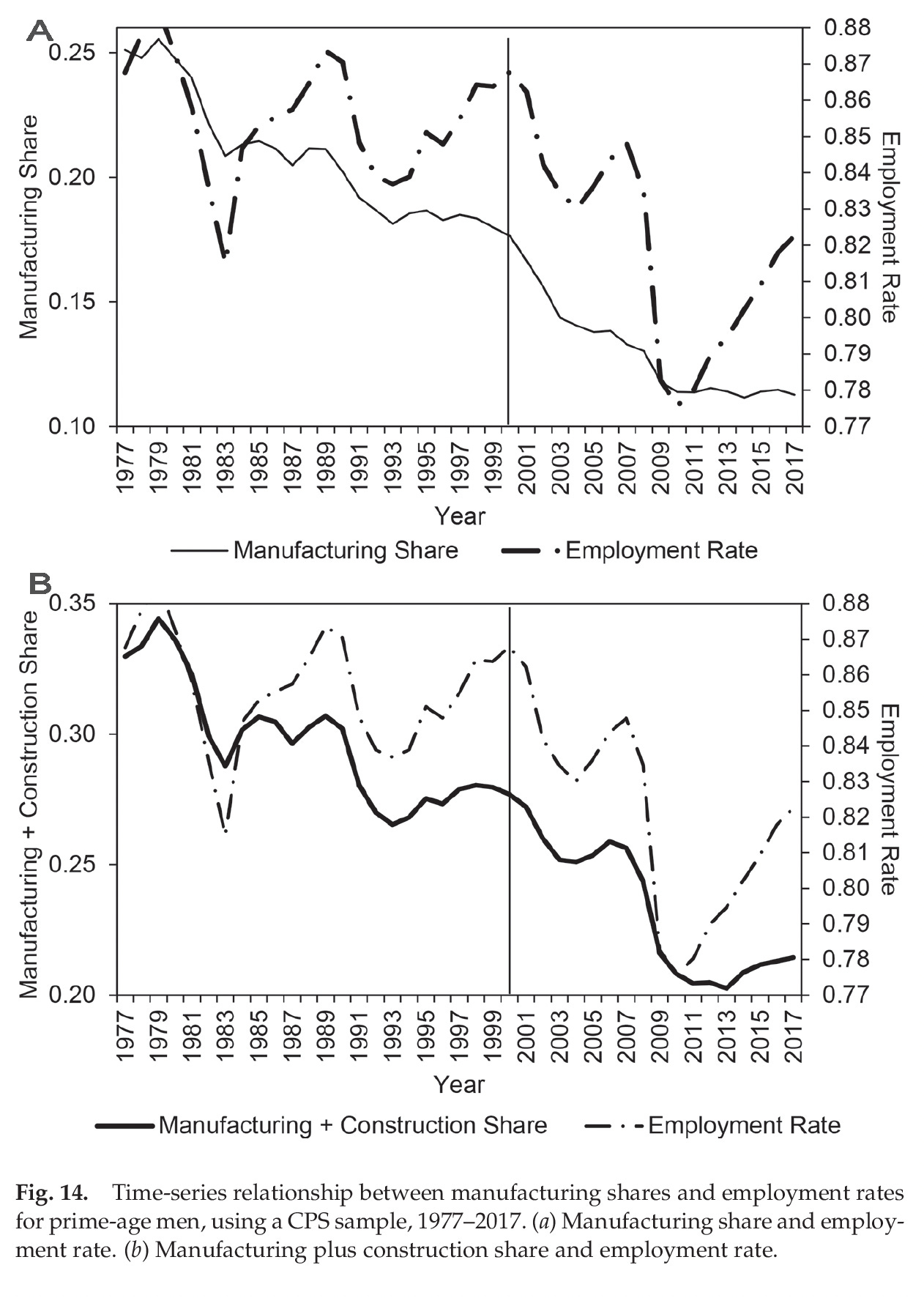

Kerwin Kofi Charles, Erik Hurst, and Mariel Schwartz examine how the decline of the U.S. manufacturing sector has impacted employment rates, particularly for less-educated workers. They find that local areas more exposed to manufacturing declines experienced larger drops in employment rates and annual hours worked.

This relationship has also changed over time. While manufacturing has been declining for decades, its impact on overall employment became much more pronounced after 2000.

What changed?

Charles and colleagues suggest that in response to import shocks and automation, plants with routine tasks closed, and the remaining manufacturing jobs increasingly required higher skills. Male workers then struggled to move to new opportunities. Meanwhile, hard-hit areas saw increased use of opioids.

Automation

So is this all down to automation, being uniformly bad news?

Well, a new paper may rock your priors. Patricia Cortés, Ying Feng, Nicolás Guida-Johnson, and Jessica Pan examines how automation has differentially affected labour market outcomes for men and women in the United States from 1980 to 2017.

Though initially more vulnerable, women have shown remarkable adaptability in the face of technological change, reshaping their education and career trajectories towards higher-skilled occupations (follow the red line in Panel B).

Women have also disproportionately moved into professional and technical occupations, levelling the playing field.

To unpack these changes, Patricia Cortés exploit variation in local labour market exposure to automation across commuting zones. ‘Automation risk’ is measured as the share of workers in routine task-intensive occupations.

In areas more exposed to automation, they find that both men and women were more likely to complete college. The effect was much stronger for women, especially younger women.

In areas initially more reliant on routine jobs, women (orange) outpaced men (blue) in transitioning away from high-risk automation occupations (Panel A) and into professional and technical roles (Panel B). The steeper slopes of the fitted lines for women in both panels underscore their greater occupational mobility.

Why might this be?

Well, women’s comparative advantage in social skills, complementing non-routine tasks, may provide advantages in automated workplaces. Furthermore, women have demonstrated greater occupational flexibility and a greater tendency to pursue higher education in response to automation risks.

Demographic Ageing

Jaime Arellano-Bover, Nicola Bianchi, Salvatore Lattanzio, and Matteo Paradisi reveal another unexpected factor in the narrowing gender pay gap: demographic aging.

As older workers stay longer in the workforce and retain top positions, they inadvertently stall younger men’s upward mobility. Since the 1970s, young men’s representation in top jobs has declined more sharply than women's, compressing entry-level wages between genders.

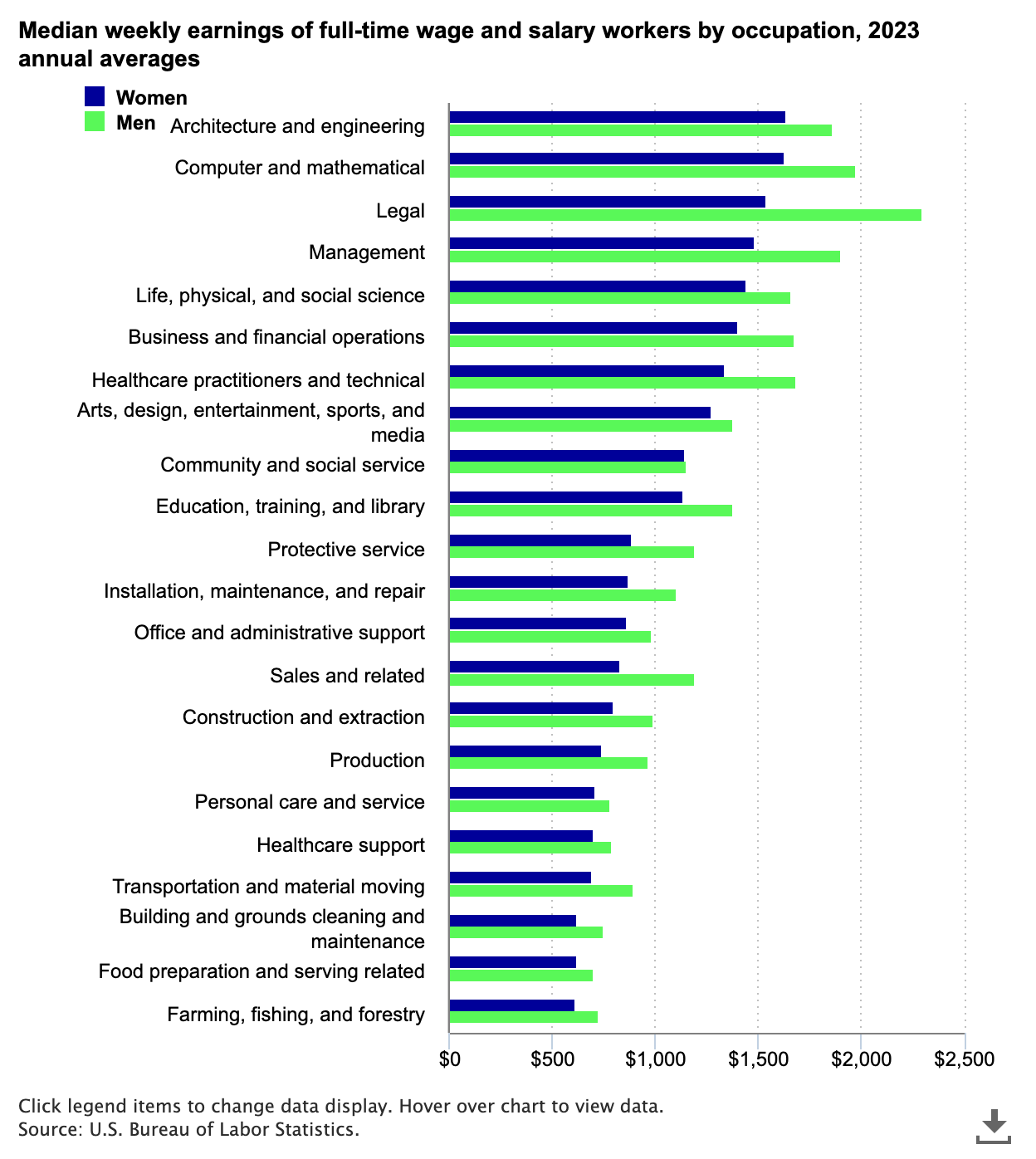

Gender pay gaps persist

Please do not misinterpret me as saying that inequalities are over! In the US last year, women’s earnings were 84% of men’s (across all cohorts, working full-time).

However, if you slice by birth cohorts, you’ll see growing parity.

Pay gaps persist due to occupational segregation, managerial promotions, and motherhood:

In the US, young men still earn more than female peers, primarily because they are consistently choosing to major in subjects (like STEM) that yield high earnings.

In Germany, female graduates are less inclined to seek managerial promotions, possibly due to aversion to team leadership.

Upon childbirth, women generally reduce their hours, and take more flexible jobs with lower pay. But this is obviously contingent on women having children….

Young men and women are converging - in the West

In terms of status and seniority, young men and women are converging. This holds at both ends of the educational distribution - though for different reasons. Without denying disparities, we do see a marked generational shift. The causes are up for debate, it’s possibly accelerated by automation and demographic ageing.

What does this mean for culture? How are men reacting?

Stay tuned for my essay next week!!

Has there really been a decrease in the male/female wage gap, though?

It seems as if the smaller gap among younger age cohorts might reflect higher levels of childlessness, rather than a secular trend.