Why is Management So Male?

Senior management remains heavily male, and honestly I’m not entirely sure why. Before diving into a new Econ paper, please share your priors:

"The Broken Rung: Gender and the Leadership Gap" by Ingrid Haegele

Ingrid Haegele finds that junior men are more likely to apply for promotions, primarily due to a greater desire for team leadership.

Sceptical? Suspicious?

Well, let’s first look at the dataset:

One of the largest manufacturers in Europe, employing over 200,000 workers.

Personnel records of over 30,000 white-collar and management employees in Germany from 2015 to 2019

The universe of job application and vacancy data within the firm’s German operations. (In this firm, employees must actively apply for internal job switches, including promotions).

A large-scale attitudinal survey of employees.

Haegele then examines drivers of gender gaps in promotion applications.

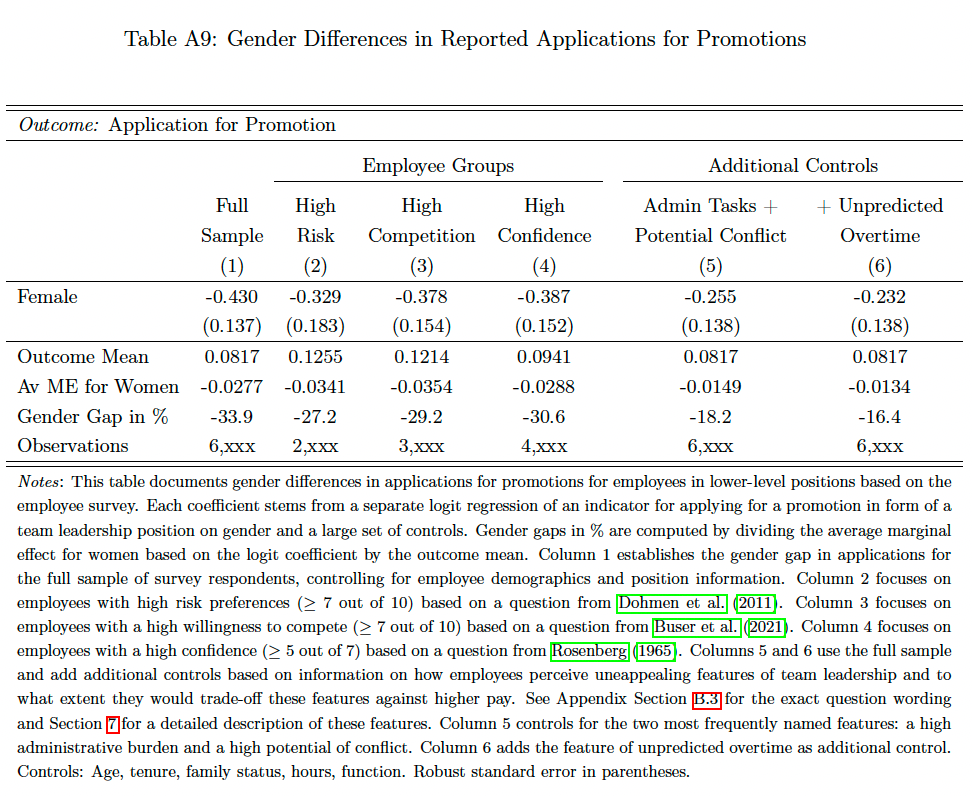

Women (compared to men) are 27.4% less likely to apply for early-career promotions

This gender gap persists even when controlling for factors like education, performance, job location, hours constraints, and family status.

Women already in leadership are not less likely to apply for subsequent promotions.

Once women do hold leadership positions, the gender gap in application disappears. This could reflect selection, or perhaps they’ve realised it’s entirely manageable?

The gender gap drops significantly among employees who have applied at least once.

Discrimination?

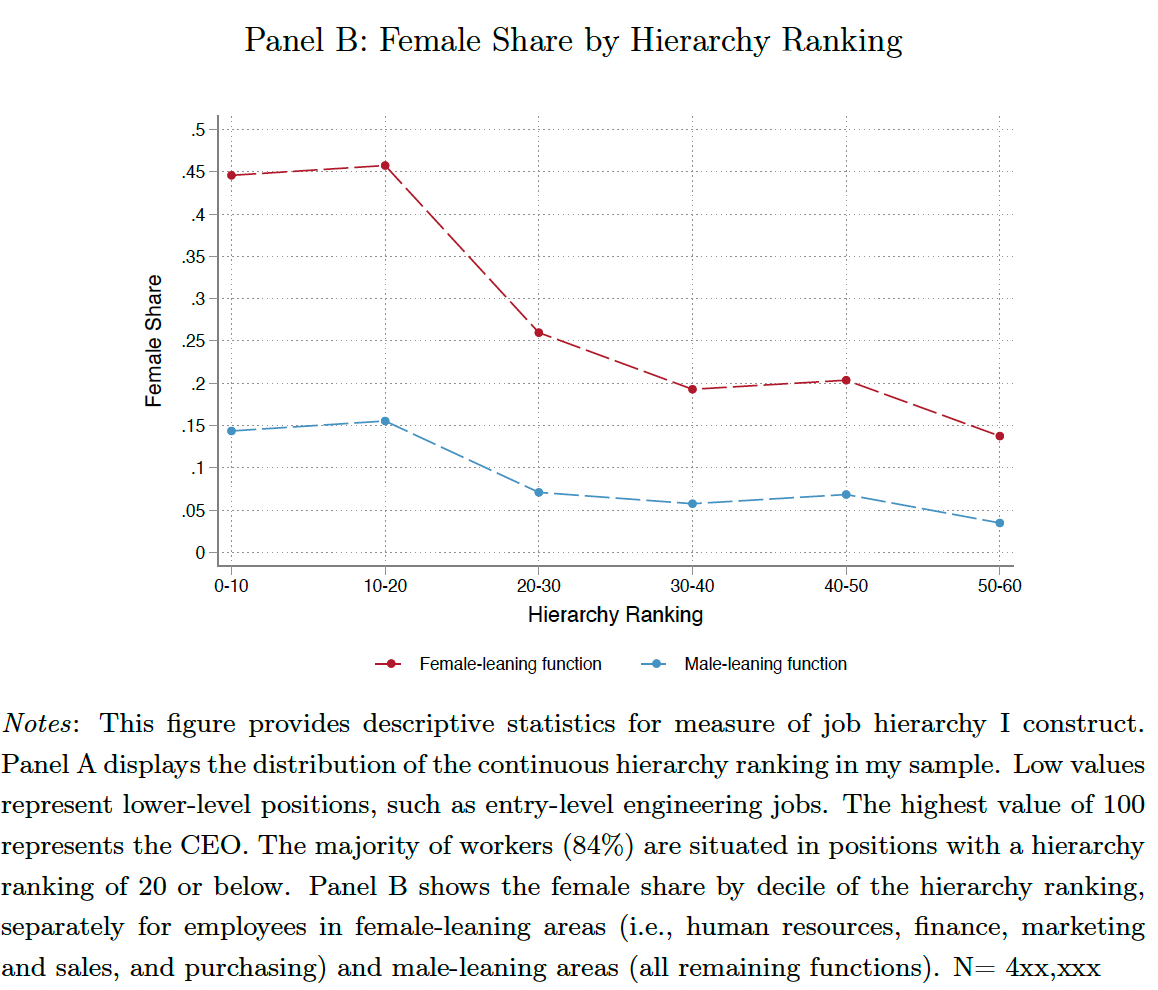

Reluctance to apply could be a reaction to perceived discrimination and the dearth of female leaders. Indeed, German management is distinctly masculine. Women comprise only 14% of senior roles in German businesses. 73% of management positions are held by men, and 59% of German firms have no female leaders.

This firm is no exception, team leadership is very male.

Given the paucity of female managers, do women anticipate rejection?

Well, women who do apply are highly successful!

Haegele finds that ‘conditional on applying for a promotion, women in lower-level positions are 23.4% MORE likely to be INTERVIEWED and 45.1% more likely to be HIRED relative to the outcome mean’.

Male dominance?

Do male networks privilege their own - building trust and camaraderie, sharing insights and information? That’s certainly my prior. Accordingly, we might anticipate that women are less likely to apply if their supervisor or network is male.

Surprisingly, women are still less likely to apply even

in female-leaning sectors (Column 4)

with female supervisors (Column 5)

in a team with an above-median female share (Column 6).

That said, women only comprise 20% of employees in this manufacturing firm. The environment is still extremely masculine; and management generally means managing men.

Expected rejection?

Do women underestimate their chances?

Surveyed employees were asked to estimate a hypothetical employee’s prospects of promotion, where the name is varied by gender. Neither men nor women expected sexism (Figure 4A).

Clearly, this is not proof that sexism is over, but it certainly encourages us to look for other potential causes of the gender gap in applications in promotions.

Confidence?

Numerous studies find that men tend to be more self-confident and self-aggrandising. Might this explain the gender gap in applications for promotions?

Men in this sample are certainly more confident, more willing to compete, and less averse to risk. But even controlling for those characteristics, men are still more likely to apply for promotions!

Work environment

Perhaps management requires locational flexibility, hurting women with care responsibilities? Actually, ‘large gender differences in applications exist even for promotions to positions that are located in employees’ current city’.

Childcare?

The motherhood penalty is real. Mothers may be time-constrained?

Even women who do not have children and are not married (which the author uses as a proxy for fertility planning) are still less likely to apply for promotions, and are less willing to take on team leadership.

Across all groups of employees at the firm, women are consistently less willing to lead teams. That is, regardless of whether they work full time, are in female-leaning areas etc.

OK. Now I’m really stumped. What on earth is going on?

Team leadership

Haegele asks senior employees to reflect back on their first promotion and identify salient features of that initial job change. Team leadership was repeatedly stressed, as especially important.

To apply for a promotion, you must want to lead a team. Might that vary by gender?

Junior staff were asked about career aspirations. What did they want in the next five years?

Men typically stressed higher pay or more team leadership.

Women differed, being 36% less likely to say they wanted to lead a team.

What do employees really want?

Surveys can be misleading, they’re prone to all kinds of bias. So Haegele cleverly asks another question: what workshop would employees value?

Women often say how to create a career without having responsibility for a team!

Some people just don’t want to lead teams

‘When asked why they did not apply for a team leadership position, 42% of respondents named the inherent position features of team leadership as the key reason (Panel A of Figure 5). This reason was named twice as often as any other, such as not feeling qualified (23%)’.

Men are more than twice as likely to apply for a promotion if it requires taking on responsibility over a team

Not all promotions require taking on responsibility over a team. Exploiting this heterogeneity, Ingrid Haegele finds a large gender gap. Men are doubly likely to apply for early career promotions that mean team leadership. This is not true for women.

This is an excellent test, which could be examined more broadly, across diverse sectors and occupations.

Lower-level female employees tend to over-estimate the challenges of team leadership

Male and female team leaders were asked about their roles, e.g. team size and frequency of conflict. Their answers are similar.

When lower-level female employees were these exact same questions, they tended to envisage larger teams and more frequent conflicts. In fact, these are misperceptions.

Lower-level women’s perceptions of team leadership are more negative and inaccurate.

‘The Broken Rung’

BRAVO to Ingrid Haegele. She’s certainly identified a plausible, under-examined driver of the gender gap in promotions, culminating in male-dominated management. It would be great to see this tested more broadly.

I think there are several possible explanations:

Biologically, men might be innately inclined to team leadership.

Men may anticipate respect as team leaders - due to everyday sexism, subtle praise by colleagues, no ‘mansplaining’, and the predominance of male managers.

Fraternal networks - men hang out together, want the best for each other, share ideas and advice, and have more accurate perceptions of management.

However, I’m not sure whether exclusionary networks are a full explanation, since many immigrants have thrived to become CEOs, despite initially being outsiders.

All the above could be true. Men might have a hard-wired preference for leadership, encouraged by daily observations of male-management and fraternal networks. Playing football with the guys after work or relaxing over beers, men share stories about their work days, bond as a group, identify with each other, and happily envision themselves in bigger shoes.

How could this be tested more broadly?

Experimental research could test the effects of:

Gender quotas for early career management - to close information asymmetries, and potential fix the ‘broken rung’.

Social bonding activities and rituals within firms help colleagues might build ties and learn more about managerial responsibilities? (Collective rituals are hugely important for building shared identity and work contributions).

Sectoral variation:

Across occupations and sectors, do senior roles with less responsibility for team management have smaller gender gaps? In law, medicine and academia, it’s possible to excel by virtue of technical competence.

Sexism :

Is women’s reluctance to lead teams endogenous to men’s expected insubordination? If colleagues are continually interrupting, mansplaining or doubting women’s ideas, then this may discourage applications for leadership.

What about less managerial encouragement or lower ratings for ‘potential’?

Cross-country variation

In egalitarian Sweden, are women more eager to apply for management because the organisational structure is very flat? If bosses are just one of the team, listening and engaging with colleagues, perhaps this removes unattractive aspects of team management.

In more hierarchical societies - like Korea, Nigeria, and Malaysia - are women even more unwilling to apply for team leadership?

See my previous essay, ‘Does Egalitarianism Enable More Gender Equality?’

If you research these topics, please let me know!

Addendum: one loyal reader shared some useful comments:

References

"The Broken Rung" by Ingrid Haegele

We need to run the numbers up against the Big 5 Psychological trait tests. I think we will find that people who test high in 'agreeableness' really do not wish to lead, because they really do not want the responsibility and competition that goes with leadership. When hard decisions need to be made, they want somebody else to do the making of them. They never want to be the bringer of bad news, or to tell somebody that they are behaving badly. Managers are the focus of resentment at times -- and they want to be loved at all times. There are plenty of men who test high in agreeableness who also don't want leadership positions. Instead of looking at 'why the men who want to lead want to lead' I think it will be more fruitful to look at 'why the people of both sexes who don't, don't'. But then, I live in Sweden.

I've spent the past 20 years on gender balancing big businesses around the world...

and my short answer to your question is leadership.

As soon as a CEO is serious about gender balancing their business (and I've had the pleasure of working with many, all men btw), they do it. It's not even that hard, contentious or slow. But 'serious' is the key word. It takes will, then skill and focus. From the whole leadership team.

Key requirements:

. leadership commitment, accountability and skill

. framing: business issue, not women's issue or HR or 'diversity'

. focus more on the dominant group, and balance as a management skill

this is a long way away from the way most companies approach gender balance. Usually, it's introduced as a diversity dimension, led by women and all about 'empowering' women. A perfect set-up-to-fail framing. We've got to stop 'fixing' women and stop blaming men, and turn gender balance into a 21st century leadership skill like any other.

It's amazing we've made as much progress as we have!