Did Boomers Shrink the Gender Pay Gap?

Older workers are staying in the labour force, keeping top jobs. Young men's progression is then blocked, keeping them on par with women.

The gender pay gap has significantly narrowed, yet still persists.

What explains these changes?

Jaime Arellano-Bover, Nicola Bianchi, Salvatore Lattanzio, and Matteo Paradisi reveal the importance of demographic aging. As older workers remain in the workforce longer, they retain top positions, inadvertently stalling younger men’s upward mobility. The gender pay gap has narrowed because young men struggle to get ahead.

The Structural Model

Their model envisions an economy with a representative firm that employs both older and younger workers in two types of jobs: higher-paying ‘top’ jobs and lower-paying ‘bottom’ jobs.

Key assumptions:

Creating new top jobs is costly.

The firm inherits a fixed supply of older workers, whose wages and job assignments are already set.

Hiring women (rather than men) in top jobs is more costly. (This is not an empirical finding, rather an assumption about the firm’s gender bias).

Wages in top jobs pay an exogenous premium over bottom job wages.

Younger and older workers are complements in the production function.

Under these conditions, an increase in older workers (due to demographic aging) has several effects:

Younger workers are crowded out from top jobs - since they are occupied by older workers.

Younger men are disproportionately affected, since they were more likely to get those top jobs.

Complementarity between young and old workers raises wages for young workers, but this effect is smaller for those in top jobs (who face more competition from older workers).

Entry level wages of young men and women are thus compressed.

Workforce ageing thus means that top jobs are already taken, so young men are stuck at the bottom. The gender pay gaps narrows!

Could that really be true…?

Empirical findings

Analysing four decades of wage data for US, UK, Canada, and Italy, Arellano-Bover and colleagues find that:

The gender pay gap has primarily declined because younger men and women are paid more similarly

The entire reduction in the gender pay gap stems from differences between worker cohorts, not changes within cohorts over their careers. Newer cohorts enter the labor market with smaller gender pay gaps, while older cohorts with larger gaps exit. This pattern holds across all four countries studied.

So it’s not that older male and female workers were increasingly paid more similar wages. They were paid differently, then left. Their departure meant that the overall gender gap then fell.

Younger men have less chance of promotion

Older workers are keeping their top jobs, and as a result young men’s career progression is blocked. Their odds have promotion have fallen. Younger men’s representation in top jobs has actually declined more sharply than women’s.

Between 1976 and 1995, the average rank of younger men at age 25 fell from the 50th to the 39th percentile of the U.S. wage distribution. Women’s position remained stable around the 30th percentile.

Arellano-Bover and colleagues state,

“Between 1976 and 1995, the probability of 25-year-old men working in the top decile of firm groups decreased on average by 6 percentage points (a 62 percent decline from the 1976 level), while the same probability for 25-year-old women fell by only 2 percentage points (a 28 percent decline from the 1976 level)”.

This is not in the paper, but let me give a little illustration. In Mad Men Season 1 (a fictional TV series about an advertising company in the 1960s), Don Draper is the Creative Director, with a corner office and his own secretary.

He is 34!!

Entry-level convergence stalled in the mid-1990s

Convergence in pay between male and female labour market entrants stalled in the mid-1990s. This is also when convergence in the overall gender pay gap stalled.

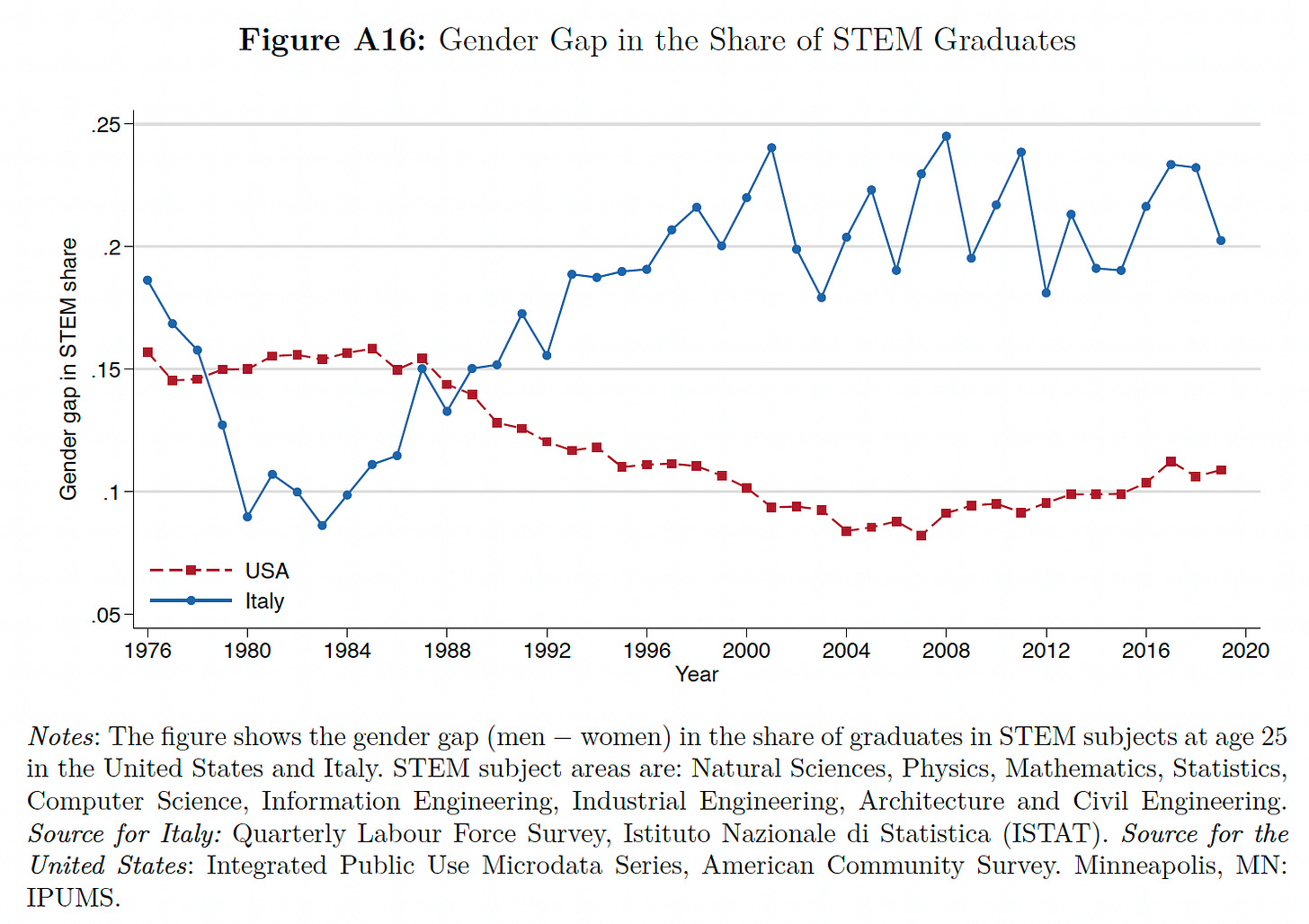

College major choices explain the remaining entry gap

Arellano-Bover and colleagues compare the weekly earnings of native-born men with different college majors. This analysis reveals that - irrespective of gender - choice in college major is strongly linked to subsequent earnings.

Young men are consistently choosing to major in subjects (like STEM) that yield high earnings. 63% of the entry gap for college graduates in the US is due to college majors. In Italy it is 51%. Women choose lower-paying fields of study.

What about the child penalty?

The child penalty does contribute to gender pay gaps, but it does not explain why the gap has declined. Even after adjusting for the child penalty, the decline in the gender pay gap stems entirely from differences across worker cohorts.

Over the life cycle of each cohort, the gap between men and women’s earnings always tends to increase. This may be due to the child penalty, women’s stronger preferences for flexibility, men’s desire for status, or just sexist bias.

TLDR

The gender pay gap has thus partly reduced because older workers are less likely to leave top jobs. Young men’s upward mobility has declined, keeping them on par with women.

But before anyone starts poisoning their older colleagues, the authors state that even if there is continued demographic ageing, this is unlikely to reduce the gender pay gap. This is because younger men have already fallen so much, and by 1995 there was very little difference between young men and women’s mean pay rank.

The child penalty clearly matters, but a major issue is that young women are still specialising in subjects that ultimately pay less. This decision may be entirely rational: money isn’t the only source of fulfilment! But for those who seek financial parity, progress is clearly conditional on women’s educational choices.

Nicely done, Alice.

What a clever idea (and stellar summary). Now I see why Biden's so adamant about sticking around for another 4 years, the man's just trying to close the gap.