Power, Prestige & Ottoman Culture Wars

From the Tanzimat Reforms to Modern Turkey!

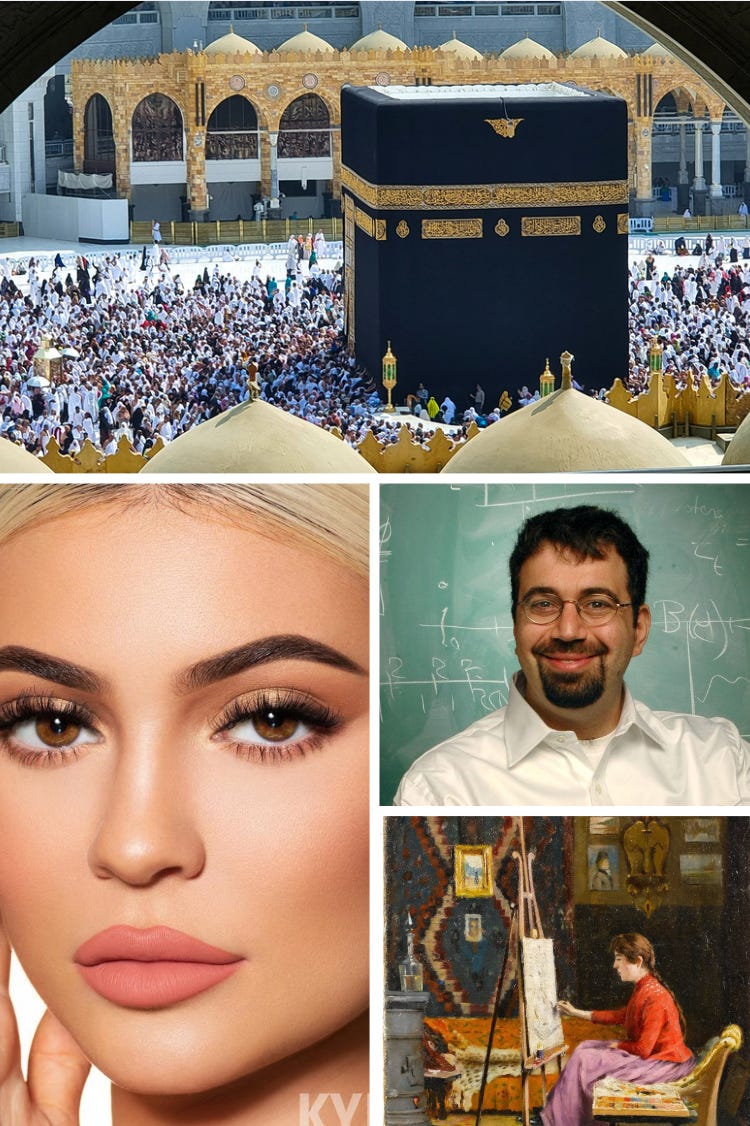

Whether you’re delving into Acemoglu’s textbook or injecting lip-fillers like Kylie Jenner, we’re all influenced by prestige, emulating icons of success. This bias emanates through prestigious networks and communications technology - think Econometrica and TikTok - where savvy influencers reshape wider aspirations.

States and law courts hold significant influence, wielding legislation to choke organisations’ private revenue, channeling taxpayer funds to favoured institutions, ripping up government contracts when relationships sour, and reshaping school curricula to mould the next generation.

So if you want to change the world, you need to understand this interplay between persuasion, power, and prestige. To see these dynamics, it helps to study culture wars over the very long-run. So saddle up, we’re off to the Ottoman Empire!

The Tanzimat Reforms

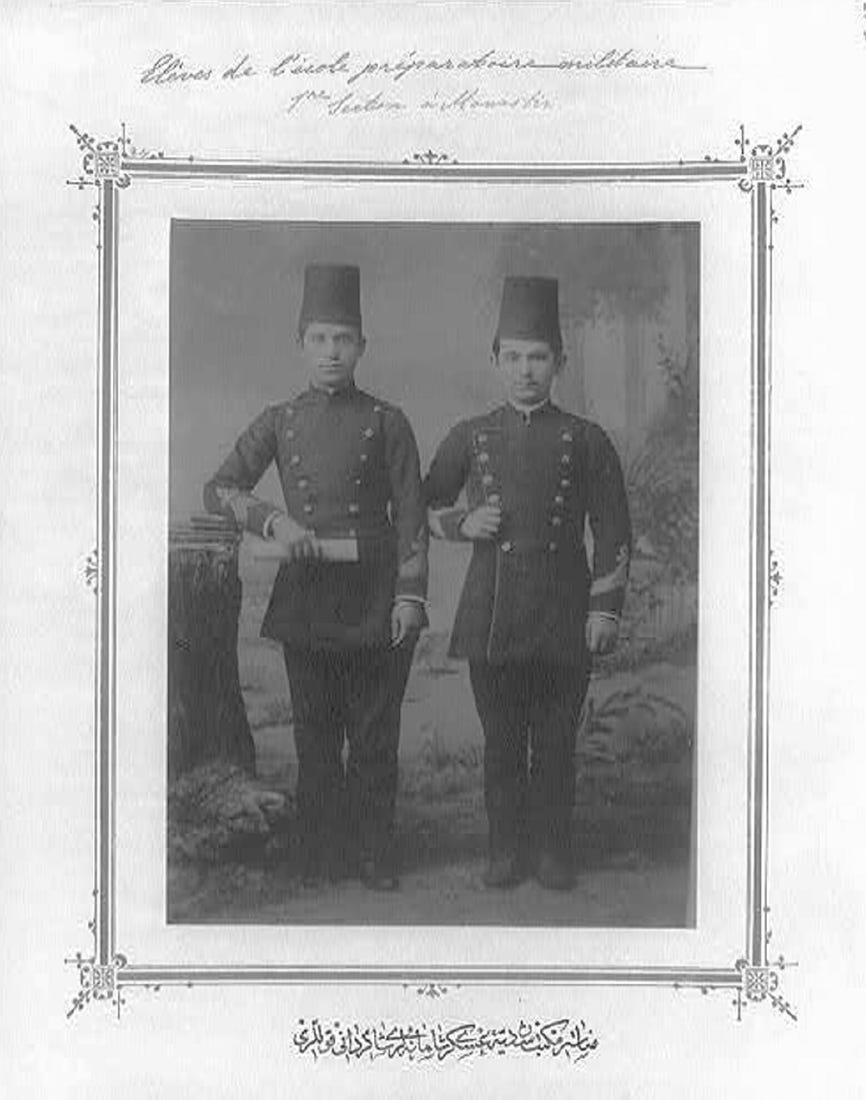

Building on Selim III and Mahmud II’s foundational reforms, the Tanzimat began under Sultan Abdülmecid I (r. 1839–1861) and continued under Abdülaziz (r. 1861–1876), aiming to modernise the Ottoman state to counter economic decline, military revolt, and territorial losses. The army, bureaucracy, legal codes, and state academies adopted Western models, with edicts like the 1839 Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane and 1856 Hatt-i Hümayun promoting equality and progress.

Sultans were never woke, but strategically borrowed from the West so as to strengthen their empire:

Addressing new medical students in 1838, the Sultan declared: “My purpose in having you taught French is not to educate you in the French language; it is to teach you scientific medicine and little by little to take it into our language” (Goodwin, 2011: 301).

“A Turk will concede without hesitation that the Europeans are superior to his nation in science, skill, wealth, daring and strength, without its ever occurring to him that a Frank might therefore put himself on a par with a Muslim” - observed Count Helmuth von Moltke, brought from Prussia to train the army (Goodwin, 2011: 302-303).

Threats came from the janissaries, Kurds, Balkan Christians, Muslim ulema, as well as Russian and European powers fuelling nationalist movements, battering the borders. Financial crises exacerbated the need for defensive modernisation.

Abdulhamid II’s (r. 1876–1909) approach was rather pick ‘n’ mix. He embraced Western technologies and administrative reforms, such as railways and modern schools, while attempting to revive the Islamic faith to unify Muslims against aggressors. Under his violent despotism, minorities were persecuted while Armenians were massacred.

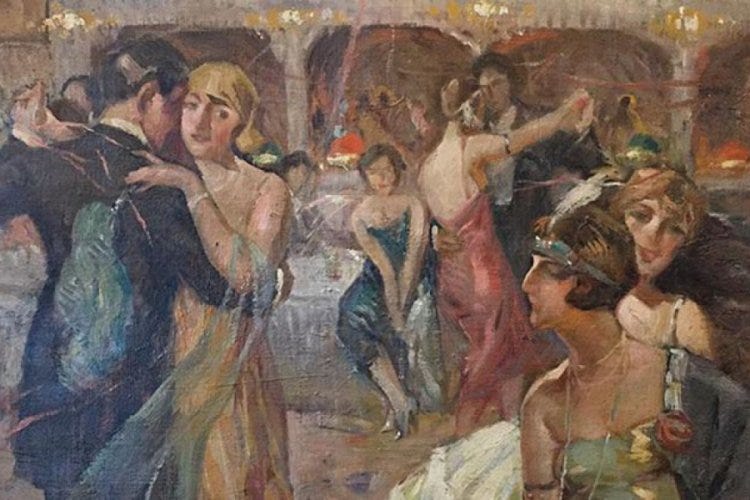

Defying Islamic proscriptions on image-making, Sultan Abdülaziz commissioned Western-style portraits, while Ottoman buildings channelled European baroque, rococo, and neo-Gothic. Western curricula were adopted at the Royal School of Engineering, Military Medical College, Military Academy, and the College of Public Administration, and European novels gained a wider readership among Istanbul elites, broadening horizons. At home, families ceased sharing a central tray of food on the floor; instead sitting upright on chairs and tables, each with their own plate and cutlery.

While the Ottoman Empire was authoritarian, cultural evolution wasn’t just top-down. As schools taught a Westernising curricular, this triggered local adaption, emulation, as well as resistance.

Elevating Western Prestige

The Education Act of 1869 introduced school inspections, required all schools to submit their textbooks, while reforming Muslim mektebs and medreses - seeing them as backward, unable to deliver economic development. Instead, state initiatives often positioned Western culture as a beacon of progress.

Mustafa Reşid Pasha (Ottoman diplomat and chief architect behind the Tanzimat) spent eight years in Paris and London, where he cultivated stronger geopolitical alliances and learnt new ideas for reform. Ambitious elites, funded by wealthy families or state scholarships, likewise flocked to these glittering European cities.

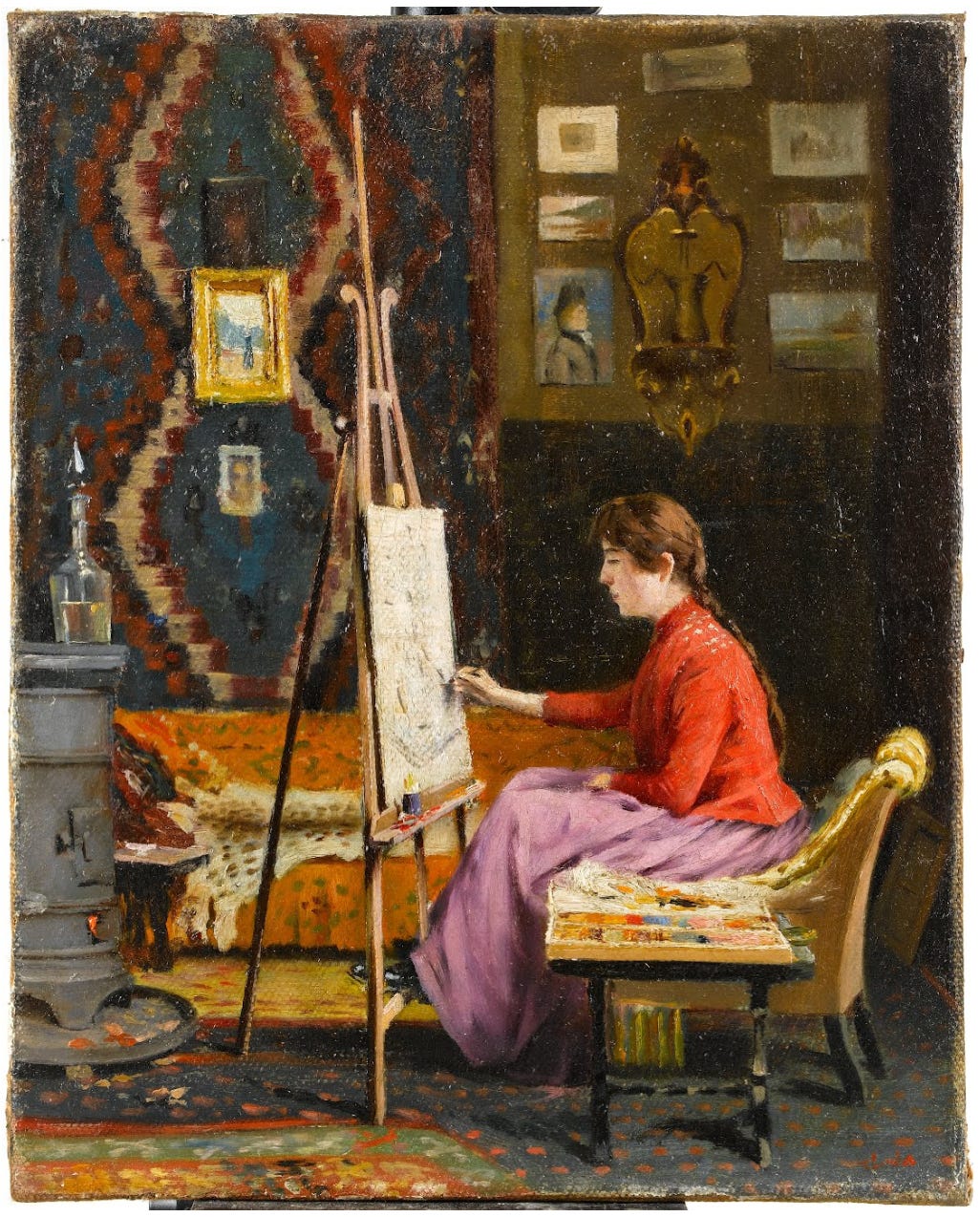

Artists like Şeker Ahmet Paşa, Süleyman Seyyid, Osman Hamdi Bey, Halil Paşa, Ruhi Arel, İbrahim Çallı, and Hikmet Onat trained abroad, returning to establish organisations and publish periodicals that embraced new pathways to status. While Istanbul did then undergo flux, we must recall that in 1900 its population was seriously cosmopolitan - approximately a third to half Armenian, Greek and Jewish.

By studying art history, I do not claim that paintings were a major vector of cultural change - 85% of the Ottoman Empire was rural hinterland!! Rather, these artworks provide a useful visual illustration of prestige bias, transnational learning, and contestation in Istanbul. Readers will recall my past essays on pre-Soviet Hungary and Ukraine, where artists travelled for studies in Paris, then championed these styles in their national capitals.

Cultural Trailblazers

Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910) was sent to Paris in 1860 by his father, Grand Vizier İbrahim Edhem Paşa, to study law. But the young man had other ideas, and instead trained as a painter under Gustave Boulanger and Jean-Léon Gérôme, creating naturalistic paintings of family and friends, which were exhibited at salons in Paris and London. Osman married twice - both to French women.

Breaking from a conservative past when men’s honour depended on female seclusion, Osman painted his wife’s portrait, bringing her identities into the public sphere.

Back in Istanbul, he wielded institutional influence, transforming the Imperial Museum into an archeological museum, also founding the School of Fine Arts

Halil Paşa (1857–1939), a Military Academy graduate and son of the Imperial Artillery Arsenal’s director, emerged as a remarkable talent. He spent eight years in Paris, training under Jean-Léon Gérôme and Courtois , earning accolades at the Paris Universal Expositions, with his portrait “Madam X” winning a medal (much like Larry Summers praising your paper at the NBER Summer Institute).

While Ottoman military schools taught western painting styles, Islamic proscriptions limited them to landscapes and still life. Halil’s return brought the avant-garde, amplified by his own status as assistant director of the Imperial Museum, leader of the School of Fine Arts, and frequent exhibitor at Istanbul Salons in the early 1900s. In 1908, Khedive Abbas Halim Paşa invited him to Egypt, where his work was greatly admired.

Ottoman Westernisation wasn’t just driven by the state, it thrived on the allure of Western prestige, drawing talent to Europe and sparking Ottoman innovations.

Stretching Boundaries of Permissibility

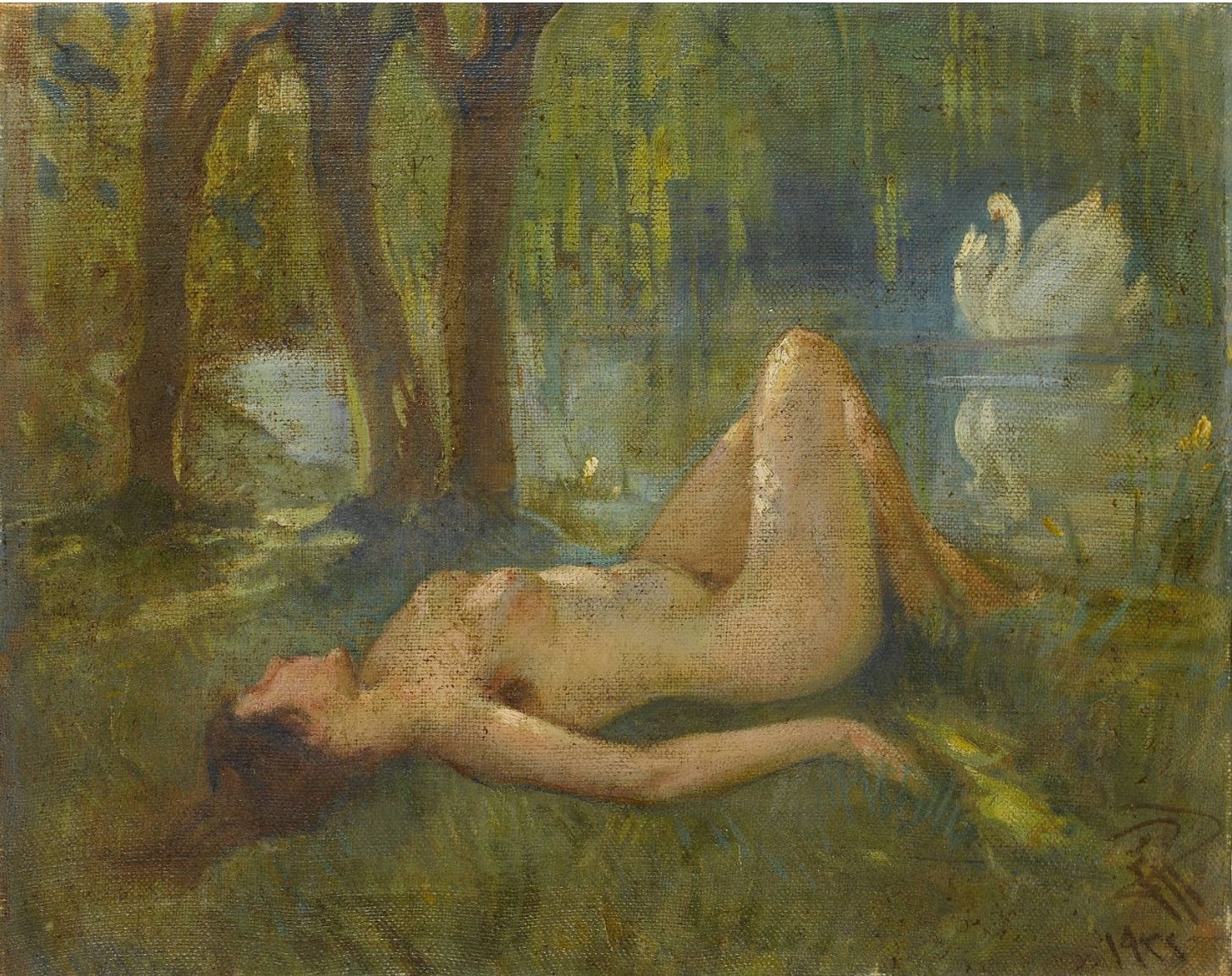

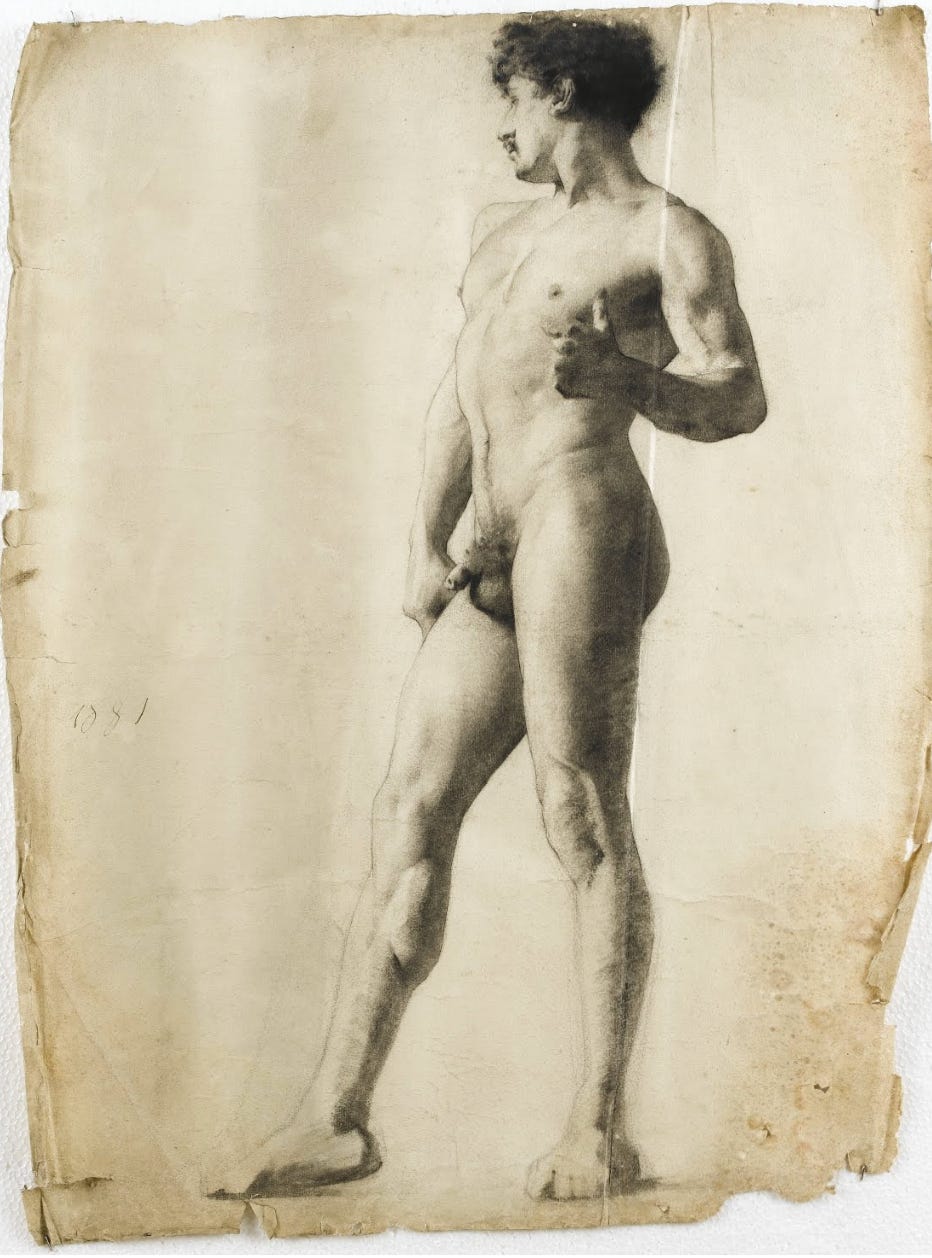

Western art education has long deemed live nude models as fundamental - Econ 101. But for Ottoman societies that privileged modesty, this was absolutely unthinkable - downright heretical. When Istanbul’s Academy of Fine Arts opened its doors in 1883, nudes were strictly off limits. Even clothed women were forbidden.

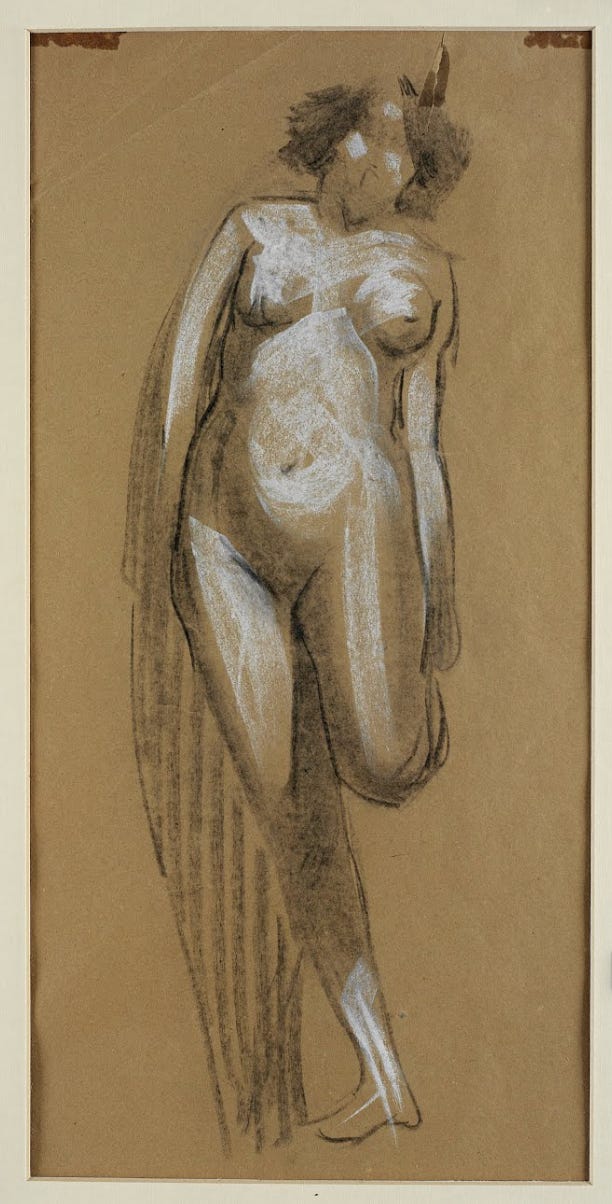

Halil Paşa and İbrahim Çallı’s nudes were thus extremely subversive. Regrettably, I don’t know whether these were publicly exhibited in Turkey.

Networks of Influence

Hasan Vecihi Bereketoğlu (from Cairo) studied under Halil Paşa and at Paris’s Julian Academy. Returning East, he became Director of Fine Arts at the Community Centres, and administrator of the Association of Fine Arts. Ottoman institutions were now under new leadership, with radically different ideas of propriety.

Subversives had to tread carefully. Step out of line, face the Sultan’s wrath.

Leaping towards Liberalism?

Culture is always a battle for power, prestige and persuasion. The 1908 Constitution, restoring parliamentary authority and championing individual rights and press freedom, marked a liberal triumph.

Privileged young men continued to further their studies in Europe. İbrahim Çallı for example worked in the studio of Fernand Cormon and finessed his skills in impressionism. With the outbreak of World War I, he returned to Paris alongside Nazmi Ziya Güran, Avni Lifij, Feyhaman Duran, Namık İsmail, and Hikmet Onat. In Istanbul, they taught new methods to students, curated exhibitions and published art periodicals.

Modern Struggles for Power & Prestige

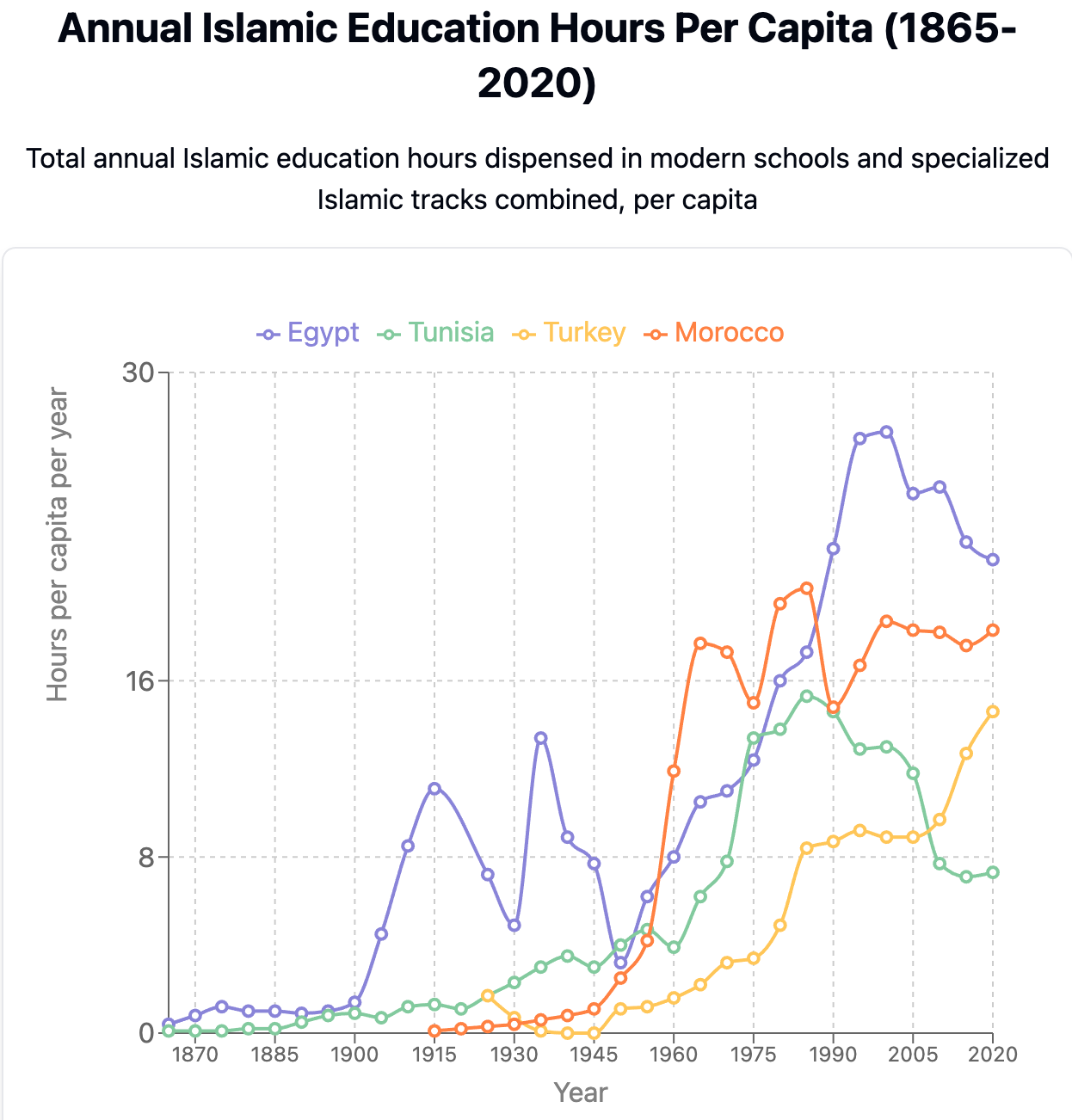

Atatürk and post-Ottoman leaders sought to curb religious authorities, elevating secular nationalism. During the 1930s and ‘40s, religious education was eliminated in Turkish public schools. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Turkey’s film censors rejected depictions of namaz (ritual prayer), the ezan (call to prayer), and any references to the Quran in contemporary settings. Scenes showing imams or hocas (preachers) were cut, as were depictions of religious marriage ceremonies (imam nikâhı). Religion was intentionally marginalised.

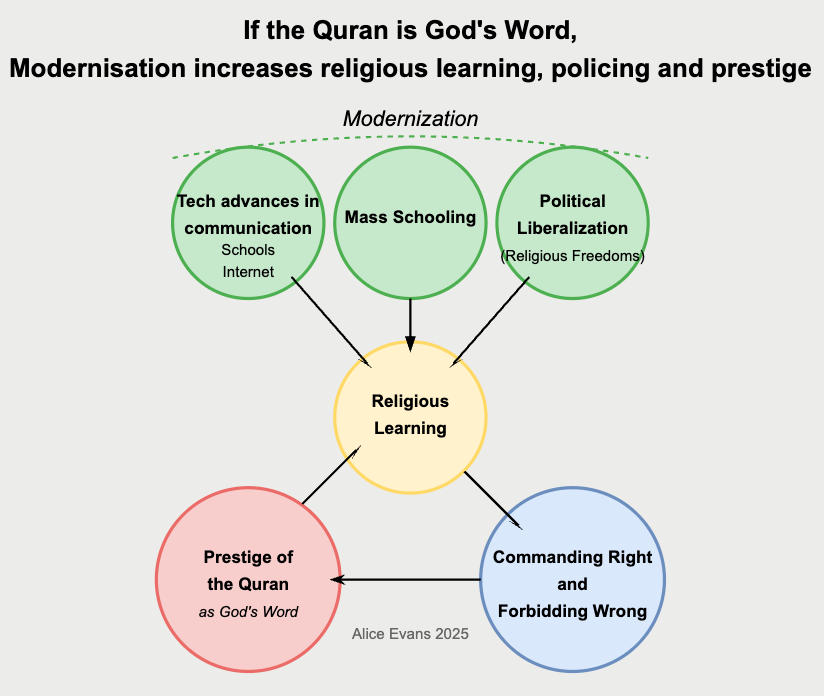

As Middle Eastern and North African states grew wealthier, they steadily increased school enrolment. Yet, with the majority still Muslim and viewing the state as the custodian of Islam, activists pushed for greater religious instruction. In Turkey, this was reintroduced as an optional subject in primary schools in 1949 and in secondary schools in 1956, before becoming compulsory in 1982. Thus, although religious instruction diminished as a proportion of the curriculum, the extended years of schooling for a growing number of children ultimately led to greater overall exposure to religious teachings.

This resurgence clashed with secular deviations, sparking tensions. Alarmed by illegitimate deviations and shirk, religious authorities mobilised communities, urging piety. This ignited a powerful feedback loop - as young men commanded right and forbid wrong, organised at universities, women reveiled, and growing numbers voted for religious parties.

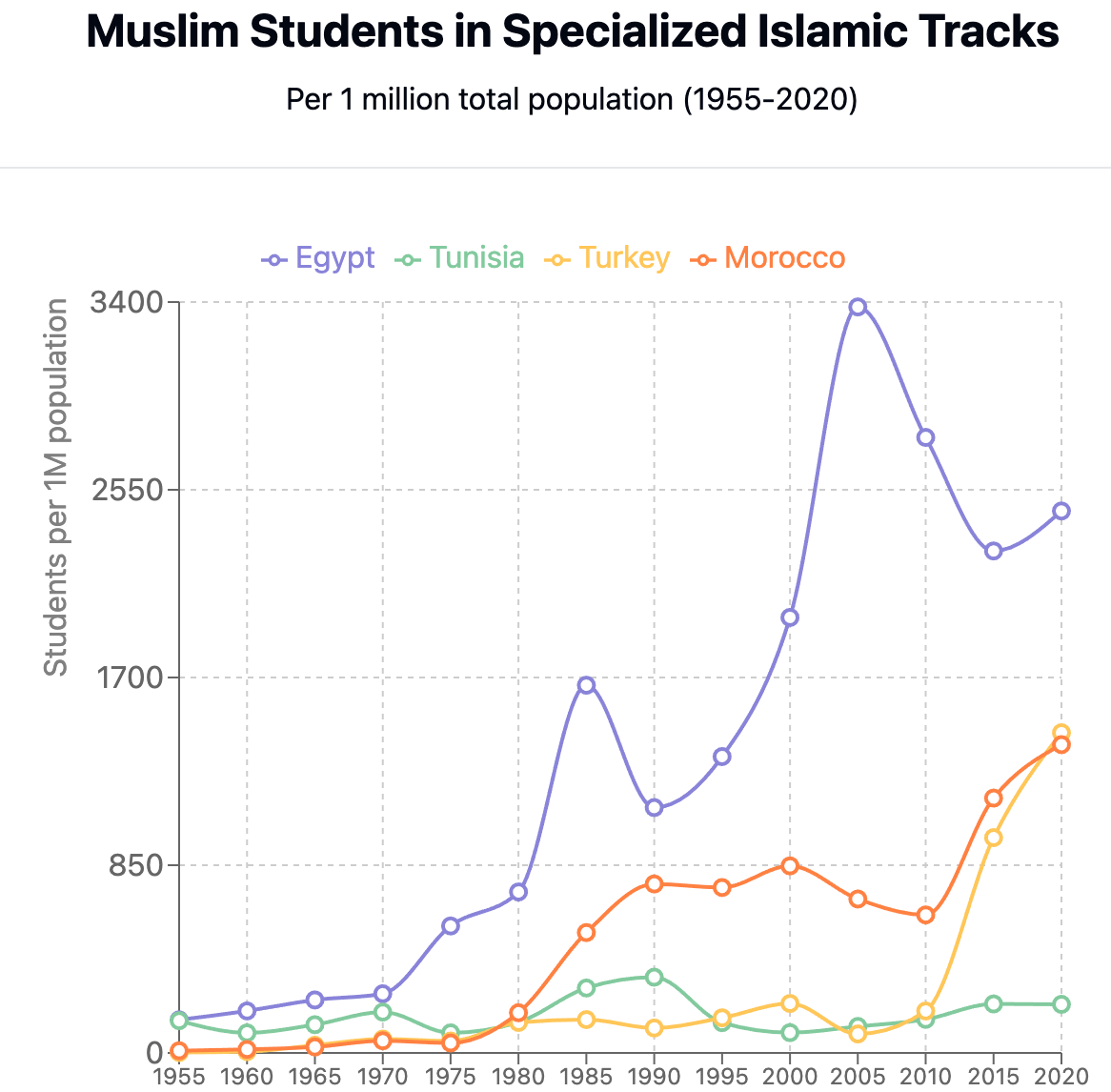

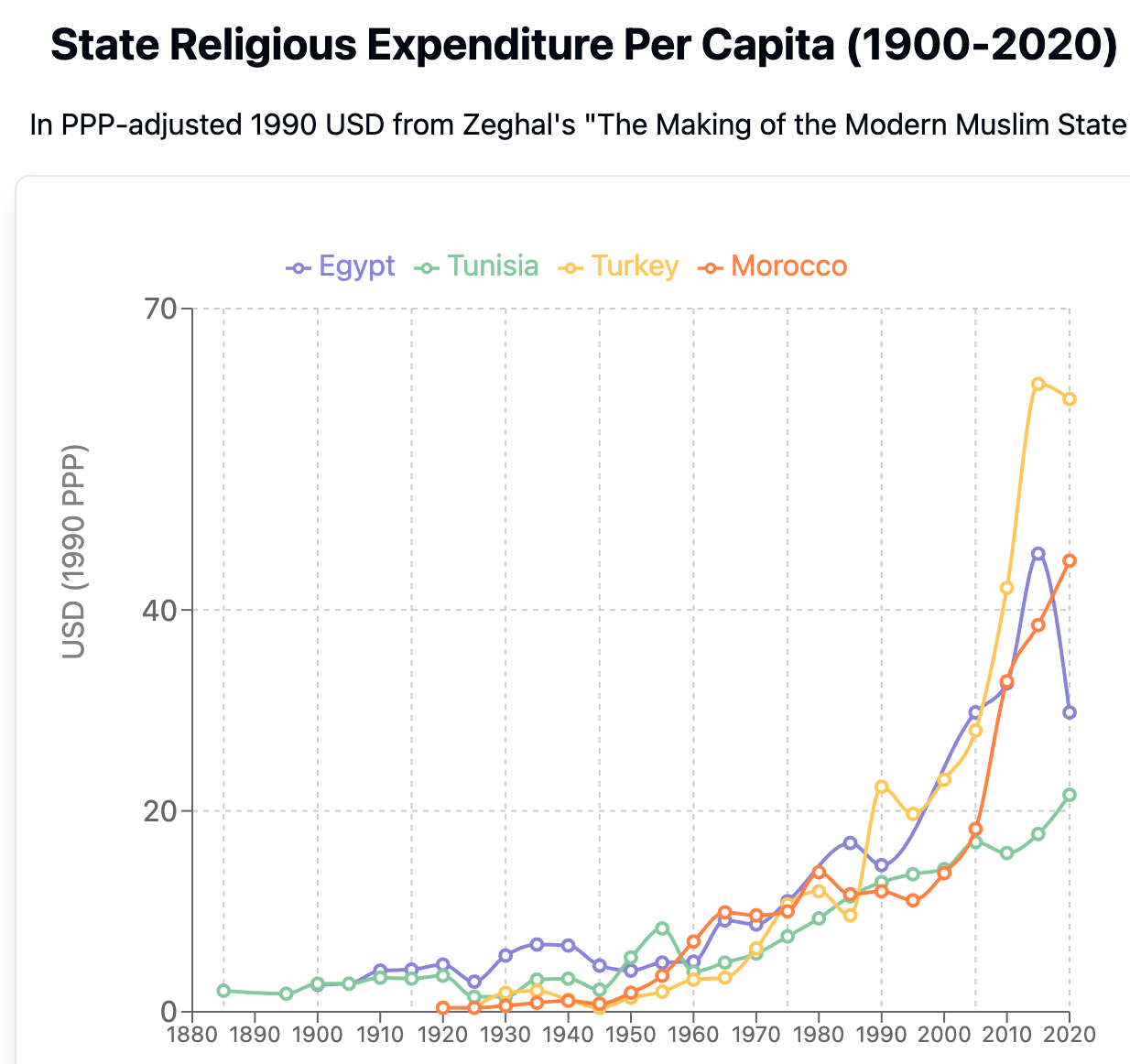

After the Justice and Development Party (AKP) was elected into power in 2002, it increased state religious expenditure per capita to over 70 USD PPP-adjusted - outpacing Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco. Turkey then witnessed a massive rise in Islamic graduates, deeply versed in the Quran and Hadith. Malika Zeghal estimates that Turkish children born in 2020 will be exposed to an average of about 1,000 hours of Islamic instruction. This represents 15 times more Islamic education than the average lifetime exposure for children born a century earlier.

State educational funding not only raised the supply of religiosity but also increased labour market demand for qualified graduates, reshaping pathways to prestige.

Who has Power & Prestige?

If you want to promote particular values, there’s actually much to learn from Ottoman and Turkish history, where states have strategically channeled taxpayer funding to patronise preferred institutions and reshaped school curricular to guide the next generation. When pathways to prestige shift, this encourages wider emulation, some young people choose to embrace these ideas but also organise stronger networks and harness the latest technology to propagate these new ideals.

BEWARE! This approach is fraught with risks. Every society is shaped by a unique cultural inheritance, setting boundaries of permissibility. If one group pushes too far beyond these limits, and the elastic band of social tolerance snaps, this triggers resistance from opponents. Likewise, if economic progress only benefits a narrow elite, leaving disadvantaged groups behind, they may seek alternative alliances that offer them status and significance. This pattern is evident in the Global Islamic Revival and contemporary US.

In Istanbul today, cultural struggles remains fraught, as the AKP leverages state power to punish and intimidate its political rivals. Surveys nevertheless suggest that those self-identifying as religious have declined to 46%. In the conservative district of Fatih, sects impose strict rules, forbidding women’s public visibility. Yet, a two-minute walk to Kadir Has University reveals a liberal scene. Queuing alongside students at Starbucks, you may be the only one without a crop-top!

This autumn, I’m returning to the Bosphorus, looking forward to see my Turkish and Iranian pals! 🙂

Related Essays

"The Making of the Modern Muslim State" by Malika Zeghal (REVIEW)

What Explains the Global Islamic Revival? (my paper)

"Practicing Islam in Egypt" and "Salafism": Podcast with Aaron Rock-Singer

Art and prestige bias:

Great first sentence: Wether you re delving...did not expect that!

The first owner of the painting L'Origine du Monde (The Origin of the World), was the Turkish-Egyptian diplomat Khalil-Bey (1831-1879). He himself probably commissioned it, in 1866, from the French painter Gustave Courbet. Khalil-Bey was a flamboyant figure in Paris Society in the 1860s. He put together an ephemeral but dazzling collection devoted to the celebration of the female body. Eventually he was ruined by his gambling debts. (Google the painting!)