"The Making of the Modern Muslim State" by Malika Zeghal (REVIEW)

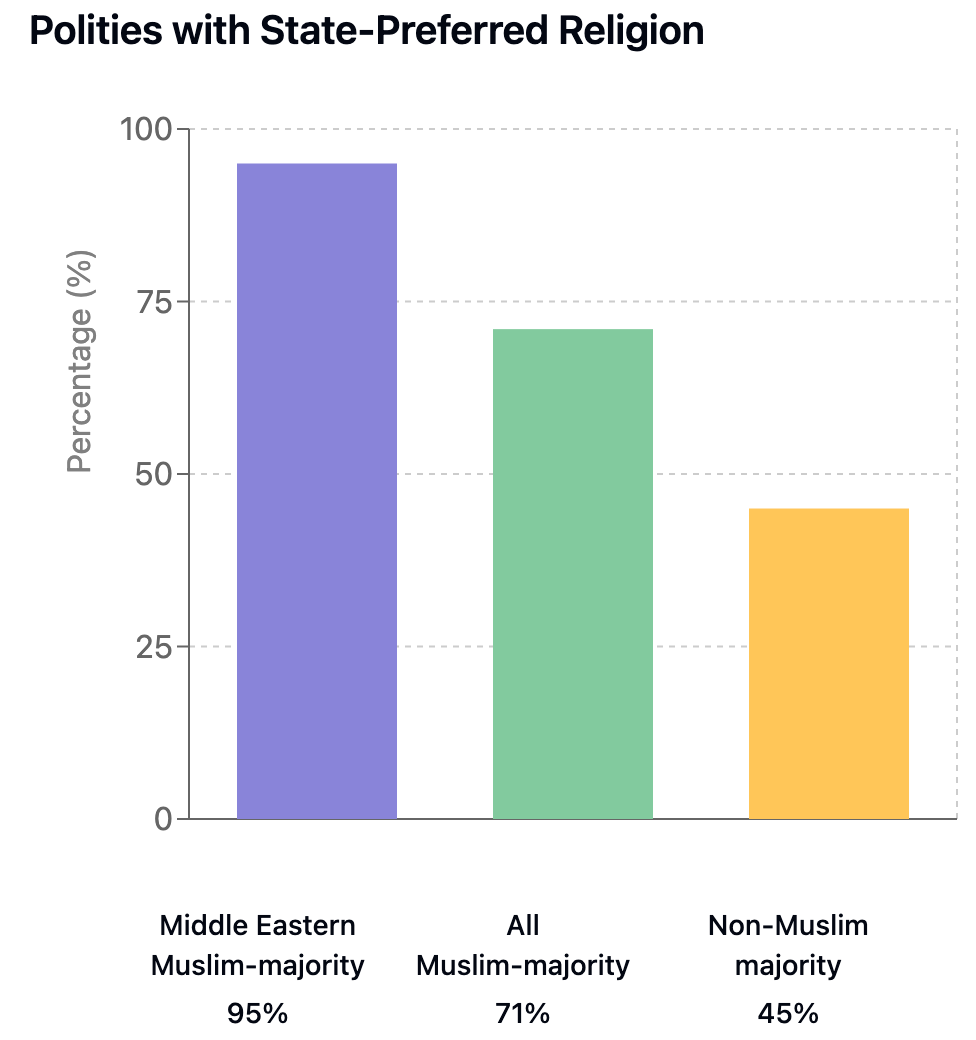

95% of Middle Eastern Muslim-majority polities enshrine a state-preferred religion. Among Muslim-majority polities worldwide, that figure is also pretty high - 71%. But for non-Muslim majority polities? Just 45%. What explains this great religious divergence? Why are Muslim, especially MENA, countries more likely enshrine religious laws?

Is this an inevitable feature of Islamic states, or was it enabled by a particular set of circumstances? If so, which? Hypotheses vary! Existing scholarship on the Global Islamic Revival tends to focus on country-specific factors – Egypt’s economic stagnation, Turkey’s religious associations, Iran’s religious authoritarianism, Sahelian state weakness, Pakistani return migration from the Gulf, repression in Uzbekistan, Indonesian’s resistance to secular schooling. But could there be a common thread?

Let me strongly recommend Malika Zeghal’s new book, “The Making of the Modern Muslim State: Islam and Governance in the Middle East and North Africa”.

Seriously, it will rock your priors!

Did Educational Expansion encourage Religiosity?

Zeghal’s argument is four-fold:

In 1900, MENA’s Muslim leaders concurred that the state should be the custodian of Islam.

Education thus included instruction in the Quran and Hadith.

As states expanded and grew wealthier over the 20th century, they increased educational access. Even though religious teachings declined as a proportion of the total curriculum, because more children spent more years in school, this increased religious instruction across the entire population.

This religiously educated public then championed Sharia.

Curious? Let’s unpack…

What about Waqfs and Voluntary Associations?

Before digging into Zeghal’s hypothesis, let’s first assess competing drivers of religiosity. Is state provision really so central? Other scholars have emphasised waqfs and voluntary associations.

Timur Kuran famously argued that waqfs (Islamic legal institutions) impeded market capitalism and reinforced authoritarianism. Prescriptions were laid down by the founder, which subsequent caretakers were obliged to follow. These strict stipulations prevented managerial autonomy, creating no room for manoeuvre. Lacking the capacity to influence the services they consumed, Kuran argues that Middle Easterners had little opportunity for political expression.

Cooperating with other waqfs was actually forbidden - claims Kuran. Middle Easterners were denied opportunities to jointly tackle social problems, organise collective campaigns, choose group leaders, and hold them accountable. Waqf rules thwarted liberal ideologies and capacities. Each caretaker looked after their own and there was no scope to coalesce. For Kuran, waqf rules led to to a self-sustaining political culture of inertia.

Fast-forward to the 20th century, the Islamic revival has been often been attributed to voluntary associations. In both Egypt and Turkey, Islamist organisations provided valuable goods and services. Carvalho, Rubin and Sacks suggest that members may have signalled strict piety to secure valuable ‘club goods’.

Zeghal: waqfs were marginal

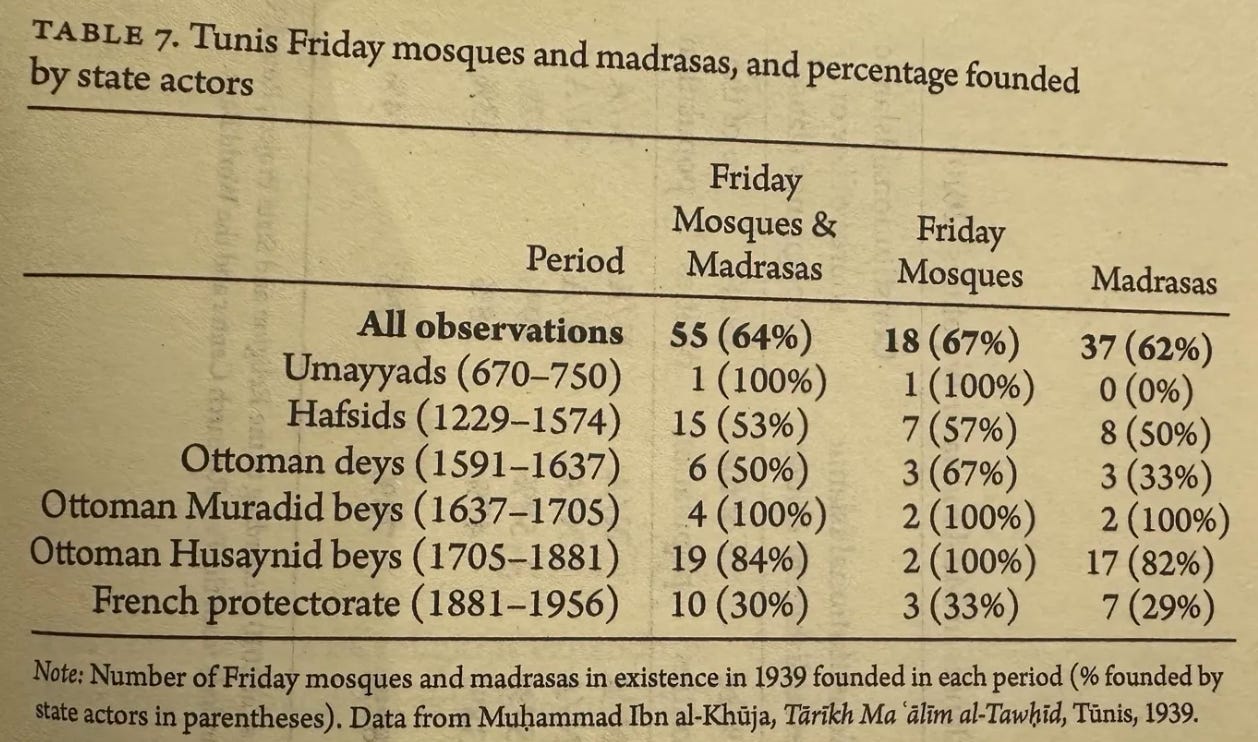

Historical data is patchy, but cobbling together the available evidence, she suggests that the lion’s share of public religious provisions was funded by the state and ruling officials. They managed and regulated religious institutions, including religious endowments, with varying degrees of centralisation.

Moreover, the state treasury regularly intervened to rescue religious institutions facing financial difficulties to ensure the continuity of public religious provision and maintain the state’s role as custodian of Islam.

In Ottoman Syria, large public waqfs (designed to benefit everyone) were financed through the transfer of tax rights by the state. Rulers and local governors used waqfs as instruments for urban development. In Damascus, numerous madrassas were founded by ruling families. Beyond founding waqfs, the sultan was typically involved in verifying their legitimacy, overseeing their registration and supervision.

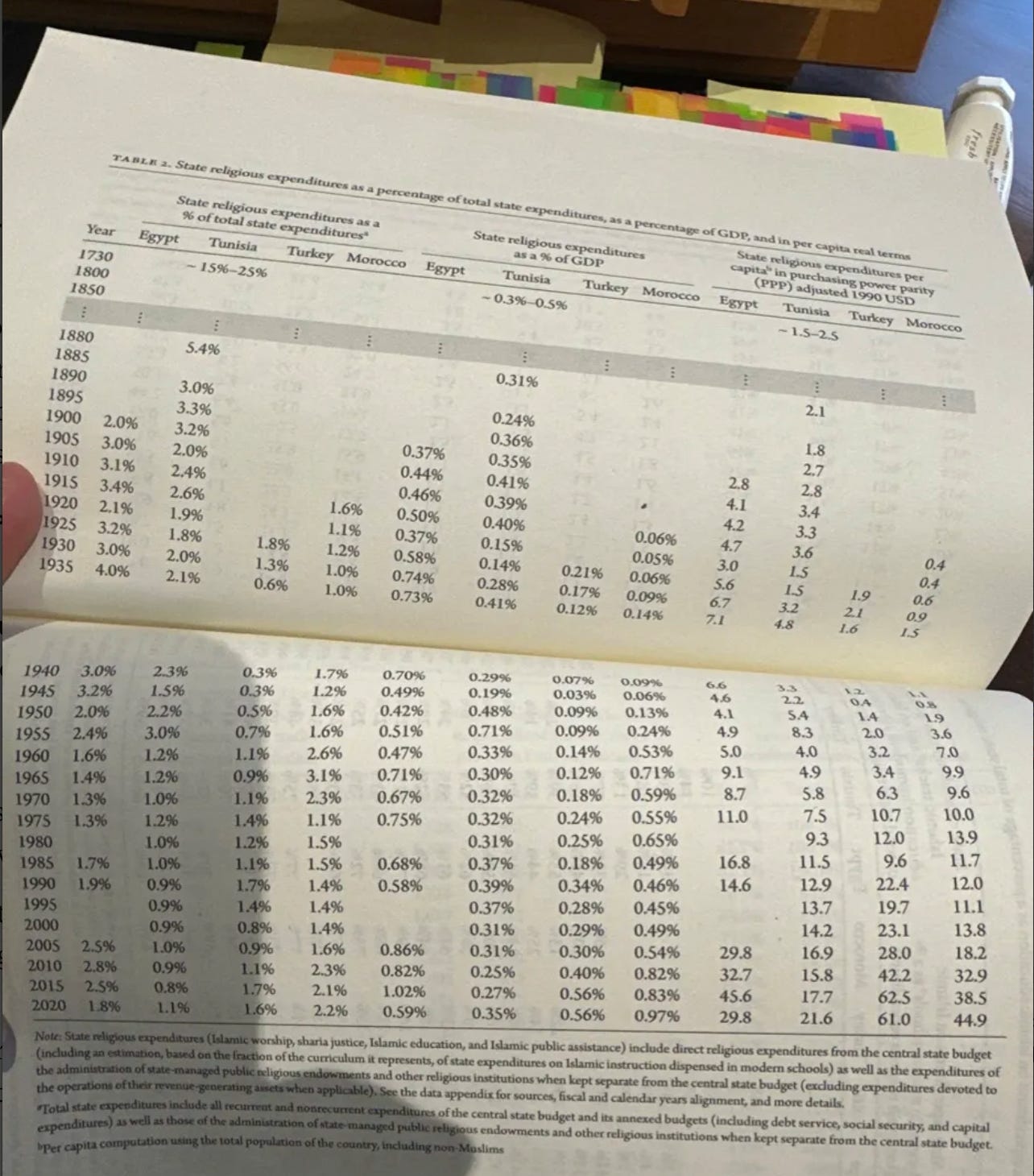

In Tunisia during the late colonial period, virtually all public religious expenditure came directly from the state budget - a pattern mirrored in Egypt, Morocco, and Turkey. When the Djamaia (public administration of religious endowments) was established in Tunisia in the 1870s, public waqf revenue funded more than 80% of aggregate public religious provisions. In Morocco, this fraction was approximately 80% in 1915, while in Egypt it stood at about 50% at the turn of the century.

In Egypt, the official Waqf Administration’s budget regularly included aid from the central state budget. This aid represented more than 20% of the Waqf Administration's budget in 1897, a third by 1944, and more than half by 1951. The state consistently sustained the Islamic missions of Egypt’s Waqf Ministry.

In 1920, Al-Azhar’s ulama actually stated it was part of Islamic tradition that the state treasury should provide salaries to religious scholars. Over in Tunisia, the Zaytuna’s ulama similarly pressured the government to increase financial support.

When Tunisia’s Zaytuna expanded enrolment, they did so with support from the state. By the mid-1930s, three-quarters of the Zaytuna’s expenditure came directly from the central state budget, and by the mid-1940s, it was almost entirely state supported.

Together, this suggests the relative importance of the state.

Waqfs weren’t necessarily that rigid!

Intriguingly, a 1916 detailed budget of the Djamaia suggests that more than 40% of its net revenue was diverted from their original foundations. In Egypt, yearly budgets of the Waqf Administration published in the Official Gazette after 1897 were structured in a way that obscured individual foundations’ revenue and their original aims! Contrary to Kuran’s portrayal of financial rigidities, waqf money could be redirected.

Were MENA states actually Strong?

No, Zeghal does not say this. She is not implying historic state capacity, but rather asserting its relative importance for religious instruction. Thus, when revenues were low and state capacity was limited, very few children studied the Quran.

The State as Custodian of Islam: Historical Debates

Zeghal meticulously examines early constitutional debates across the Middle East and North Africa. While liberals and conservatives tussled for dominance, all sought to strengthen the Islamic state. Debates centred on how - not whether - the state should uphold Islam.

Subversives were knocked down! Uproar erupted in 1955, when some leaders of Tunisia’s New Dustur Party’s French Federation proposed that ‘the Constitution must include a secular regime’, with the preservation of each religion’s personal status and the creation of a secular Tunisian personal status, which each Tunisian would be free to adopt’. This triggered massive condemnation from Zaytuna ulama (religious leaders), the old Destur party, and even factions within the Neo-Destur party itself. Adamantly, they firmly rejected a secular regime that would give Tunisian Muslims ‘freedom from religion’ or allow people to ‘fall into apostasy’.

Even when Bourguiba introduced the Personal Status Code in 1956 - often characterised as a progressive reform - official state narratives described it as conforming to Sharia. As Article 1 of Tunisia’s 1957 constitution plainly states: “Tunisia is a free, independent, and sovereign state. Islam is its religion”.

This same pattern repeated across MENA. The 1920 Greater Syria draft constitution and Egypt’s 1923 constitution are often portrayed as liberalising reforms, but Zeghal highlights that Islam remained paramount. Both liberals and conservatives firmly rejected the separation of religion and state.

Islamic Education

Muslim rulers have long supported Islamic education, argues Zeghal: before, during and after colonialism

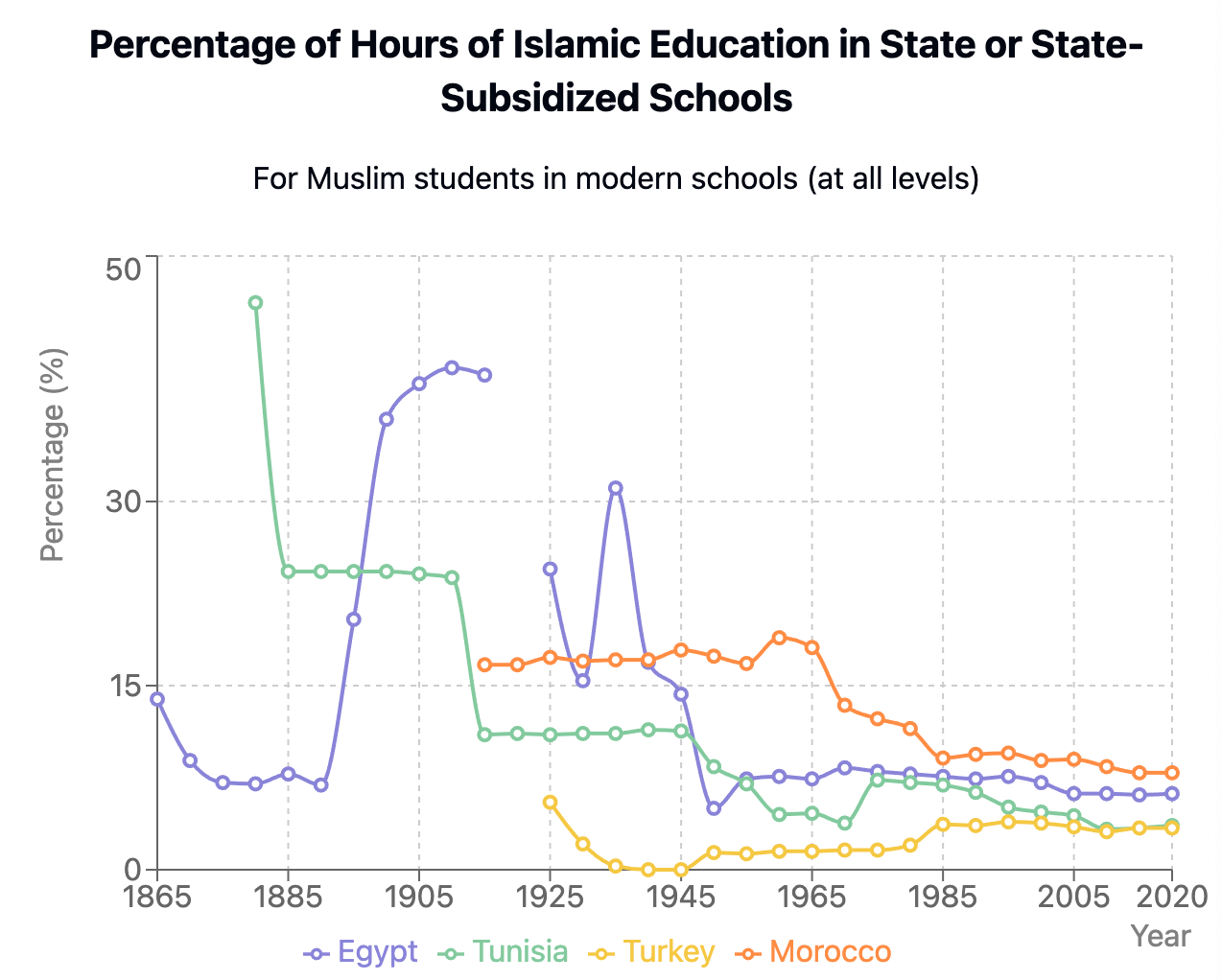

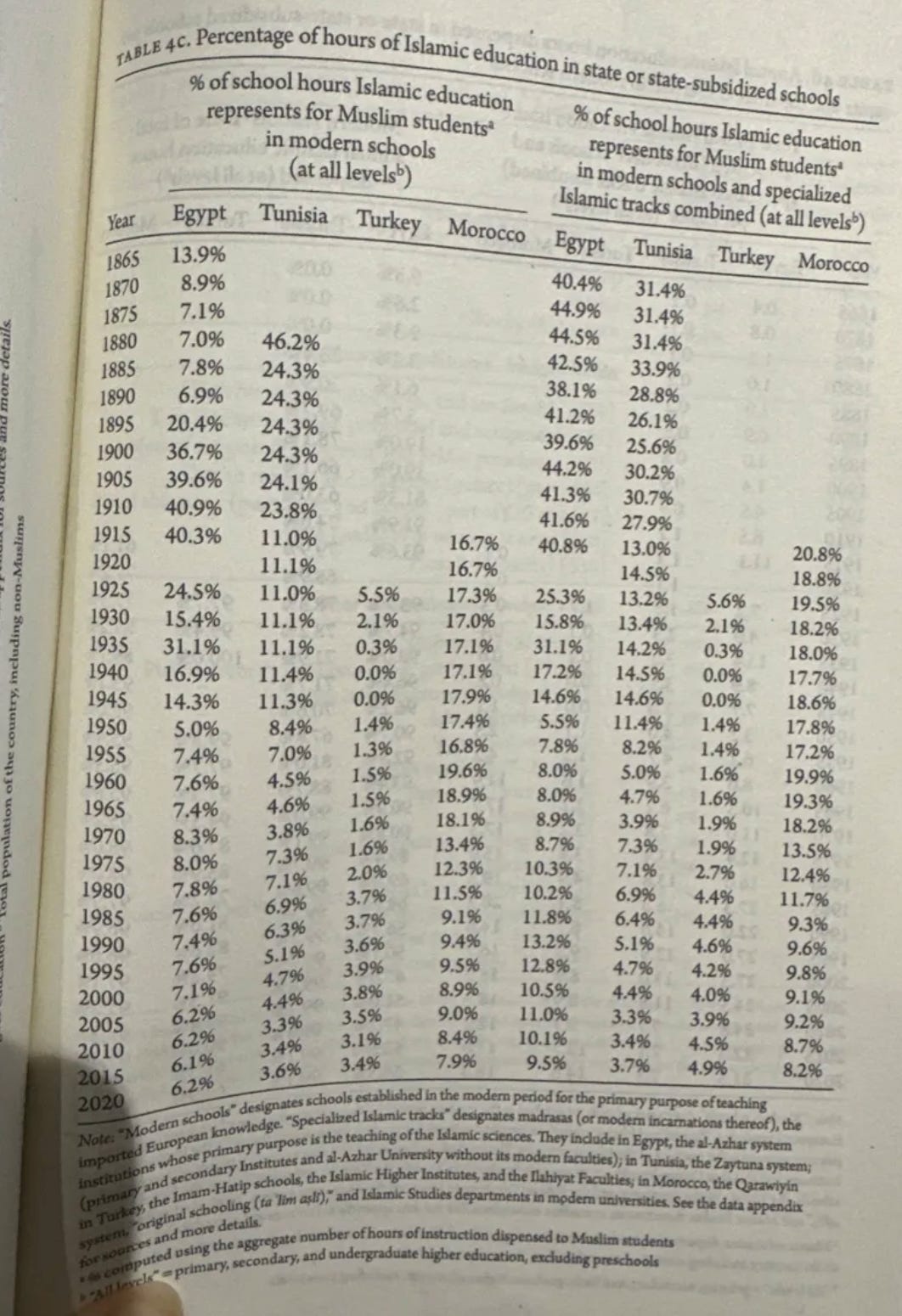

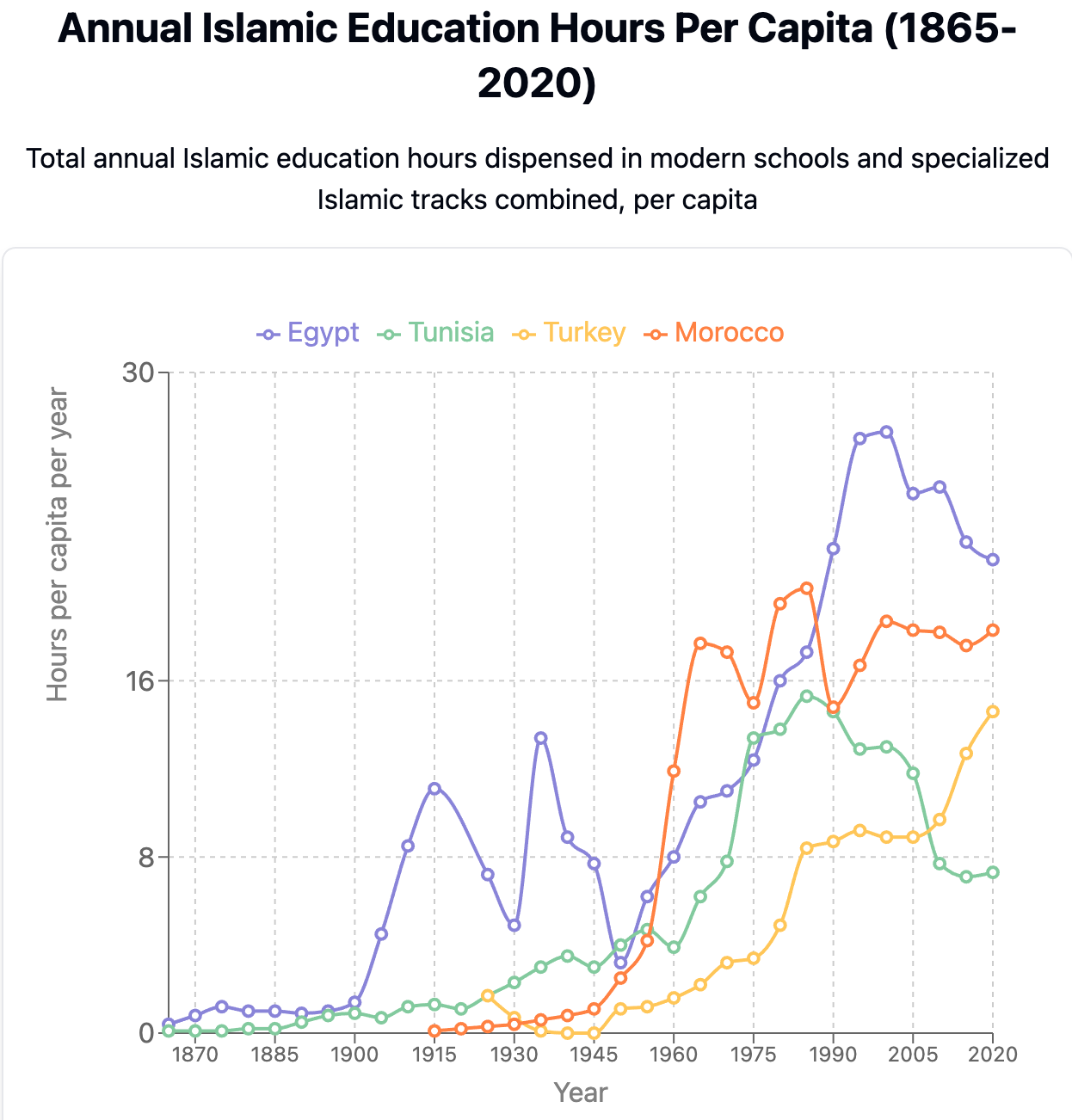

In 1816, Egypt Egypt’s Muhammad Ali’s schools included Quranic studies alongside reading, writing, Turkish, and military disciplines. By 1910, Egypt’s modern schools devoted 41% of their curriculum to Islam - as shown in the graph below.

Tunisia’s leading colleges always provided Islamic education - going right back to the Bardo military school (established in 1840), the Sadiqi school (established in 1875), as well as in schools developed during the French protectorate period.

In Ottoman Turkey under Abdul Hamid II (1867-1909), modern schools taught both religious and secular subjects. While religious education was eliminated in Turkish public schools during the 1930s and 1940s, it was reintroduced as an optional subject in primary schools in 1949 and in secondary schools in 1956, before being made compulsory in 1982.

Over the 20th century, schools increasingly taught a more diversified range of subjects - like maths and science. But, as we will see, Islam was NOT displaced!

Wealthier, Stronger & More Religious Education

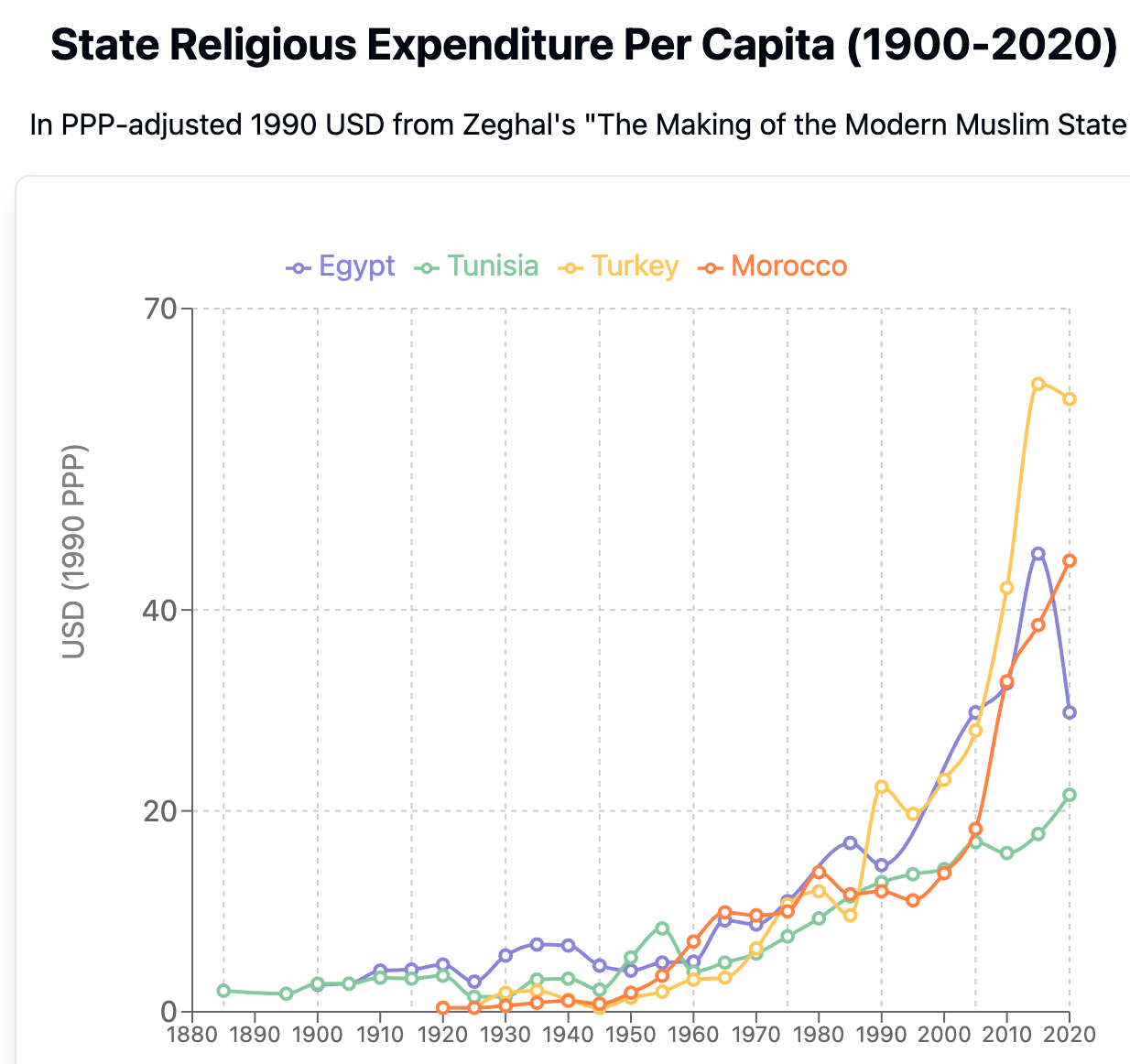

The 20th century heralded a growth in GDP per capita and state expenditure as a percentage of GDP. Greater prosperity enabled states to expand education, including religious instruction.

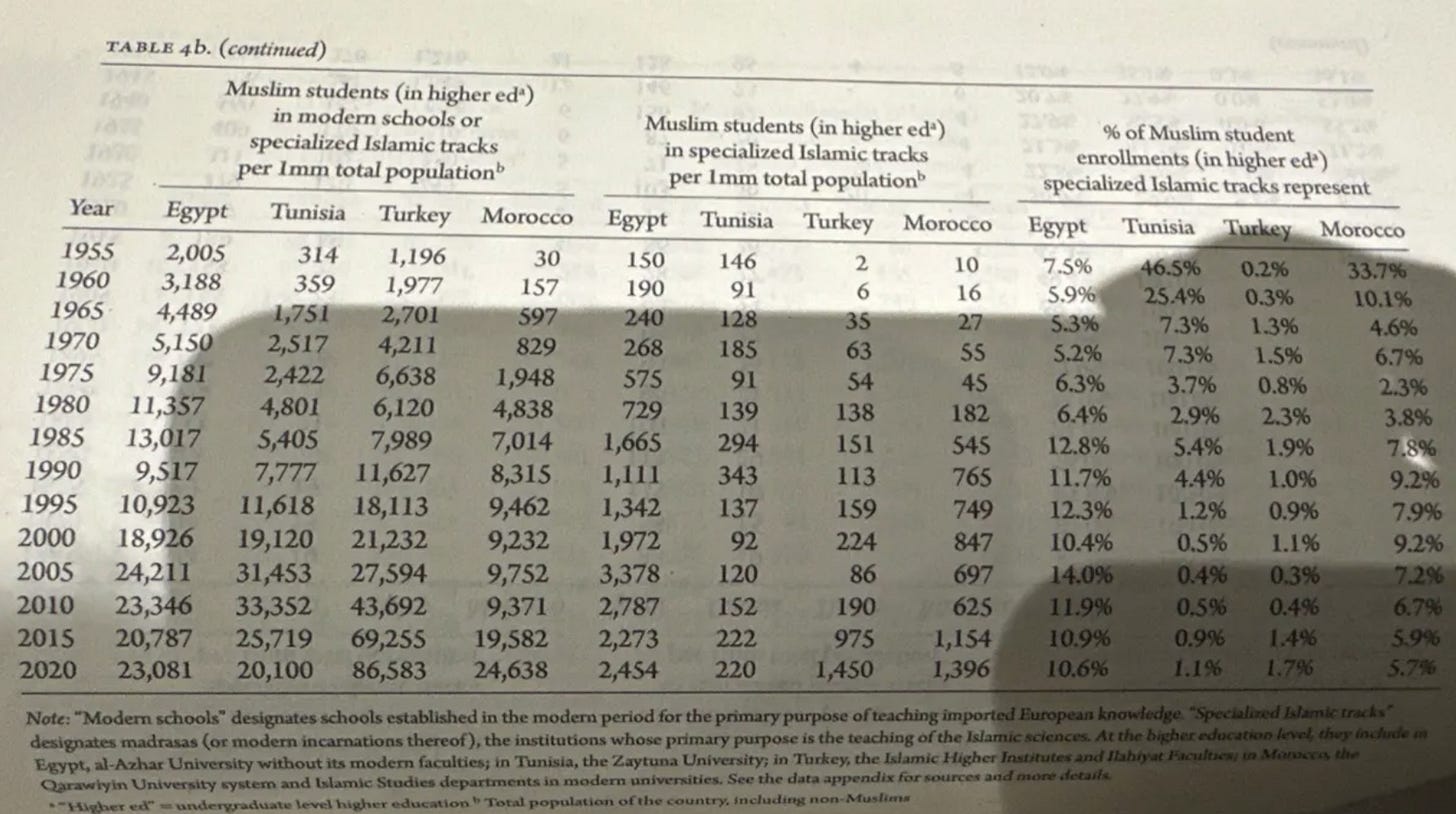

Zeghal presents fascinating tables, which I have turned into charts. Check out the phenomenal growth in per capita state religious expenditure. In Turkey, this rose from less than USD $1 in 1950 to over $60 by 2020. This is partly because Turkey has got richer, and also because the state has increased religious expenditure as a percentage of GDP from 0.09% to 0.56%!

Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco follow similar, if less dramatic, trajectories. Further, this expenditure was increasingly concentrated on religious schooling.

A more powerful state could thus champion Islam at scale. Quranic studies would no longer be confined to the ulama, but all Egyptians.

More Schooling: More Islam

Even if religion only comprises 6% of Egypt’s school curriculum, such instruction now reaches a much larger population. Village kids learn to recite the Quran.

Zeghal further estimates that Muslim children born in 2020 will be exposed to an average of about 500 hours of Islamic instruction in Tunisia and about 1,000 hours in Egypt, and Turkey. This represents 7, 6, and 15 times more Islamic education than the average lifetime exposure for Muslim children born a century earlier.

Culture is a Fist-Fight

Ofc, there was always a ‘tug of war’:

In Egypt, Hassan al-Banna, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, petitioned the government in 1928 to increase Quranic education.

In Turkey, the Imam-Hatip schools and the Faculty of Theology were closed by the secularising government in the early 1930s, only to reopen two decades later.

Bourguiba’s 1958 reform of the Zaytuna in Tunisia was particularly radical, shrinking enrollments twentyfold -a change he explicitly compared to the 1924 Turkish reforms. But this was contested! Tunisian parliamentarians subsequently pushed for greater onus on Islamic studies, lamenting that ‘the youth had become ignorant of the most basic rules of Islam’. Islamist activist Rachid Ghannouchi spoke of a ‘lost generation’, arguing that Tunisia should ‘use the Western sciences but cleanse them of Western values, their philosophy, and their way of life’.

Clearly, religious schooling is not an exogenous shock. Governments increasingly prioritised religion partly in response to demands from an increasingly religiously educated public. But this longitudinal and comparative evidence is certainly consistent with the hypothesis that religious education increased religosity.

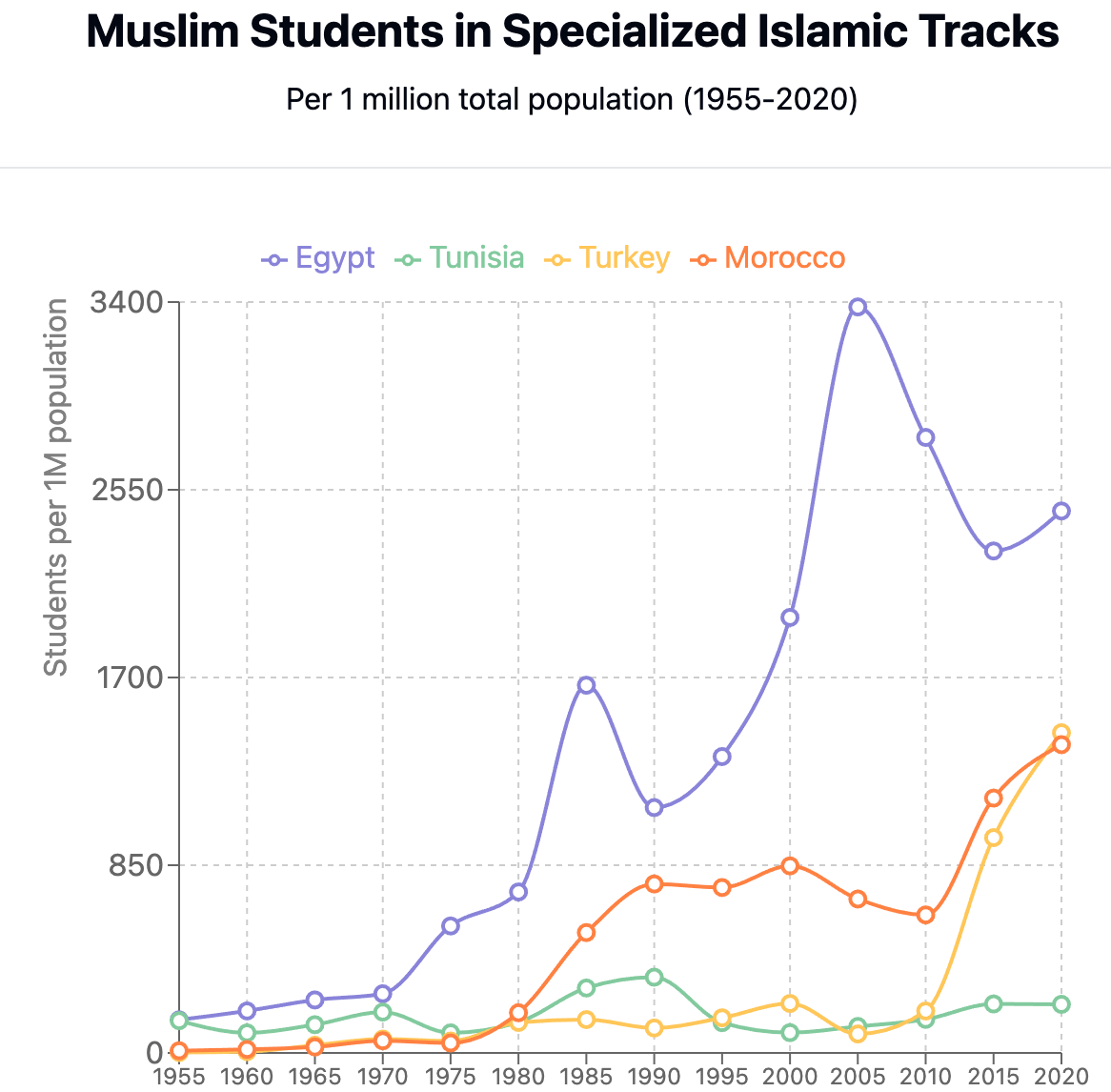

Islamic Graduates have Soared!

A rising tide of prosperity enables more young people to go to university. In MENA, many choose to study Islam. They attend specialised institutions like the Moroccan Qarawiyyin, Tunisian Zaytuna, and Egyptian Al-Azhar.

Over the 2000s, Turkey saw a massive rise in Islamic graduates, deeply versed in the Quran and Hadith. But this still pales in comparison to Egypt, where 10% of all university enrolment is Islamic.

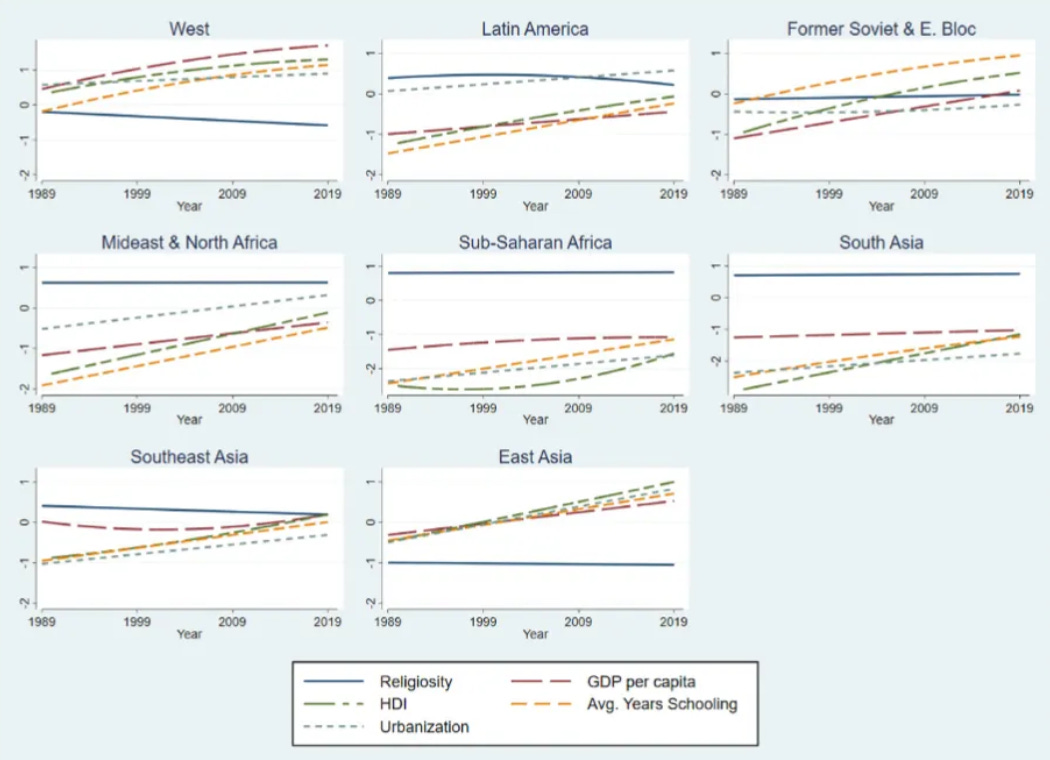

Did Modernisation Increase Religiosity?

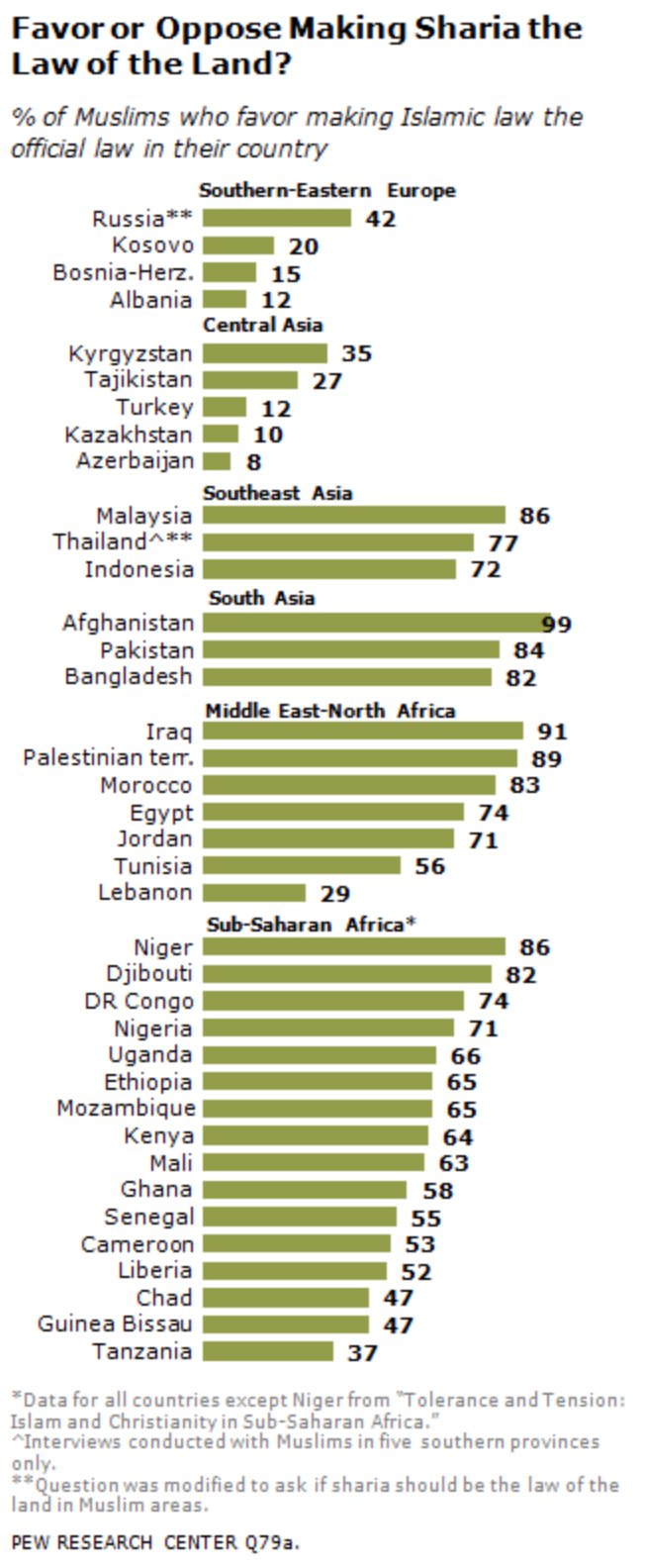

Muslim-majority polities see the state as the custodian of Islam, and as public education increased so did religious instruction. Turks, Egyptians, Moroccans were increasingly schooled in the Quran and Hadith.

Zeghal’s theory is certainly controversial! Her book is written so calmly and empirically, but takes a litany of captives. I count at least 3 major victims:

Education, wealth and modernisation will increase support for scientific, secularism and self-expression.

Waqfs and voluntary associations.

Economic stagnation drove the Islamic revival.

Actually, Zeghal insists, wealth made religious states stronger. This is perfectly consistent with Louisa Roberts’s new finding that MENA’s vast improvements in education and wealth have not weakened religosity.

While some claim that education encourages secular liberalism, I suggest this is an unfounded generalisation. Liberalism was prestigious in Europe, so as more people became educated they became schooled in these ideas. Clearly, that does not hold universally!

Bravo Zeghal! This book is seriously epic.

But you may have some lingering questions..?

Why were 20th Century MENA leaders all so committed to Islam? Why did liberal reforms fail? Was this entailed by Islamic conquests and authoritarian institutions? Or was there more contingency? Why did people keep pushing for more religious education? Was it all endogenous?

Well, here’s the great news. Next up on my podcast (“Rocking Our Priors”), the brilliant Economic Historian Jared Rubin is coming to discuss his awesome research on religion, technology and backlash!

P.s. faith schools are still legal in the UK.

It would be interesting to look at the motivations and actions of American Christian Nationalists, (see project 2025) because they appear to be taking a leaf from the Islamists as far as trashing the secular public education system and replacing it with Christian madrassas.