CENSORED: 20TH CENTURY STRUGGLES OVER CINEMA

Culture is a gladiatorial arena, rife with the possibility of disruption. Diverse coalitions have always sought to harness the latest media technology in order to propagate their narrative and mobilise widespread support. It's precisely this potential for ideological persuasion that drives struggles for state power in order to champion preferred narratives.

Human history, as I see it, is fundamentally about political competition

to control story-telling and secure ideological legitimacy.

Mythology, literature, songs, and films aren’t just fun entertainment. By praising heroes and demonising villains, they also shape expectations of what is widely revered and respected.

Governments may also seek to buttress their rule by repressing dissent and encouraging uncritical acceptance. Seldom seeing resistance, compatriots may underestimate wider support for change, choosing to conform outwardly rather than risk isolation or persecution. Importantly, these quests for censorship aren’t just authoritarian power-grabs, they can also be motivated by ideology.

Now, in celebration of this year’s Nobel for inclusive institutions, I’ve crafted an essay on the global history of film censorship!

Movies frequently depict stories about our communities in a manner that feels credible and realistic. Viewers absorb these narratives, learning what is held in high esteem and aspiring to emulate the glamorous heroes they see on screen. Political coalitions, across the ideological spectrum, have long recognised this power of cinema to shape hearts and minds. As a result, they have often mobilised to censor and control, repressing rebellious ideas.

We begin in the early 1900s, when nations worldwide grappled with cinema’s power to showcase alternatives and excite subversive aspirations! Cinema posed a unique challenge - viewed by all, unfettered by the usual guardians of morality. All countries shared a deep concern to regulate public morality. The British Empire imposed censorship in its colonies to prevent unrest, while the United States and European nations fretted over the corruption of youth.

Over the 20th century, different regimes harnessed cinema for their own ends. Totalitarian rulers in Italy, Germany, and the Soviet Union weaponised film for propaganda. But even in democracies, there was a constant struggle between freedom of expression and perceived moral threats.

Film censorship also played a crucial role in nation-building. Mexico, for instance, sought to prevent humiliating portrayals of its people and culture in foreign films. Turkey used cinema to promote secularism and build confidence in state capacity.

After World War II, the West increasingly liberalised - transitioning from strict censorship to age ratings. Meanwhile, communist and totalitarian nations maintained tight control. Religious organisations, like the US Legion for Decency and Nigeria’s Islamists, have also pushed their politicians to take action.

I share this essay in celebration of Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson’s Nobel. They’ve never actually written on film censorship, this is just an Alice Evans tribute! :-)

Here’s what coming up:

1900-1930s: Moral Panic & Control (Italy, North America, Germany, Mexico)

1930s-1940s: Empires & Propaganda (British Colonies, Italy, USSR, USA)

1950s-1960s: Cold War Cinema (Italy, USA, Germany, China)

1960s-1970s: Celluloid Nation-Building (Turkey, Italy, Chile)

1980s-2000s: Loosening Reels (USA, Ireland, Italy)

2000s-Present: Religious Mobilisation in the Digital Age (Nigeria, Malaysia, Global Netflix)

2010s-Present: State-Sponsored Liberalisation (Saudi Arabia)

Conclusion: The Cinematic Tussle

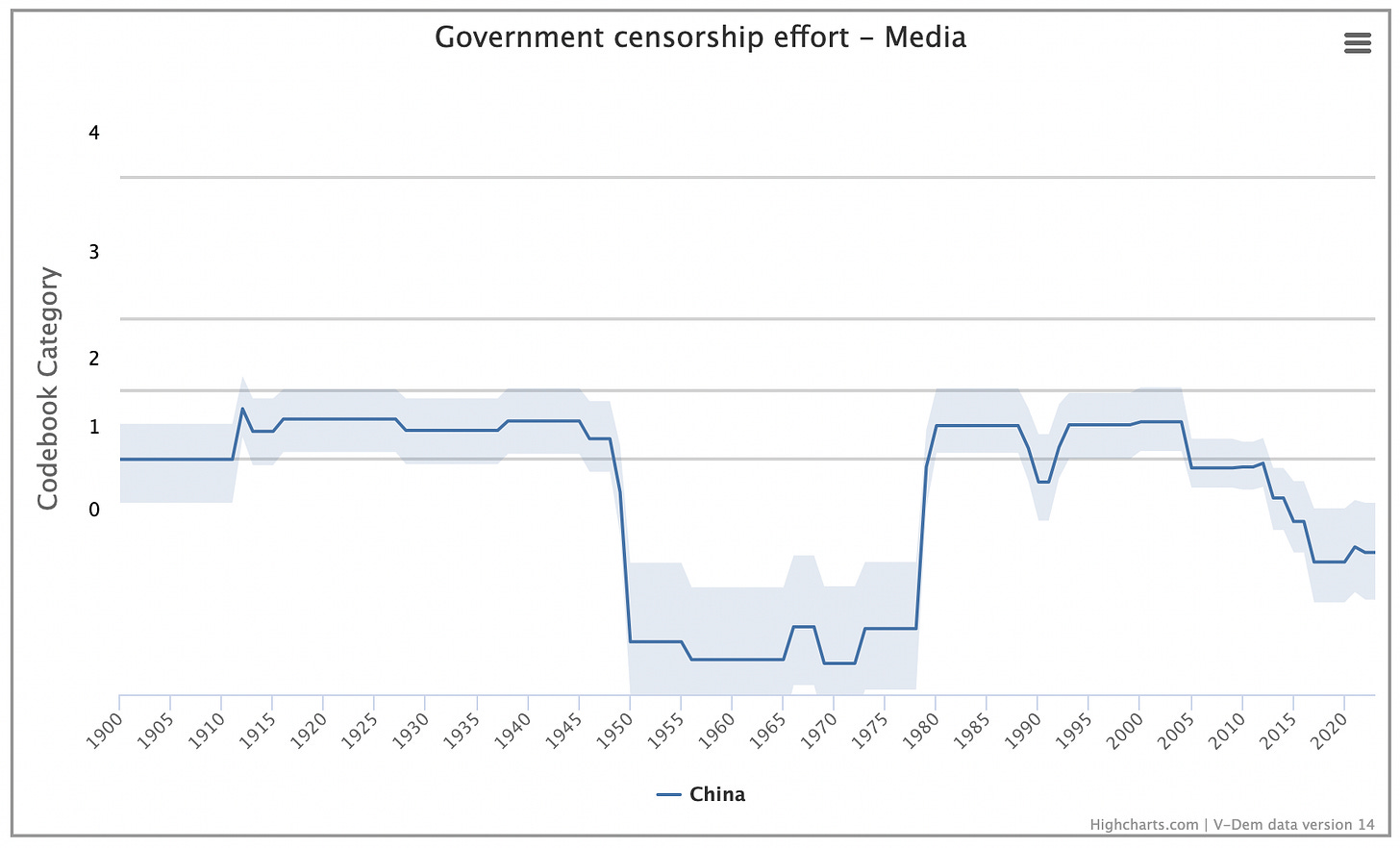

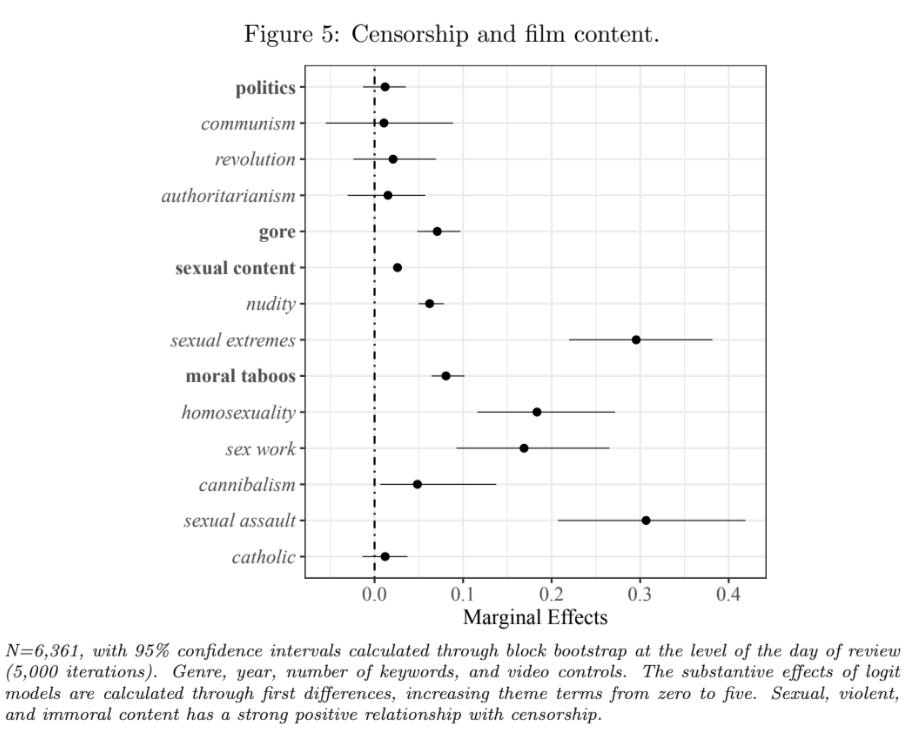

V-Dem’s graph below draws on experts’ subjective assessments of government censorship of media. A score of ‘0’ means censorship is direct and routine, while ‘4’ means its rare, and if discovered censors are punished. This is not a total compendium of censorship as it excludes non-political subjects, like religion.

1900-1930s: Moral Panic & Control

Italy

Italian film censorship formally began in 1913, born from a cocktail of moral panic and political anxiety. Conservative groups, alarmed by cinema's perceived threat to public morality, pressured the government to act. They feared losing control:

“There is something in this new form of popular spectacle that eludes institutional power and escapes the control of intellectual élites, and which must be fought arms at the ready: visual messages have an extraordinary diffusion rate and seem to work when they avoid any pedagogical intention and take on fearsome antagonistic functions”.

The Catholic lawyer Giovanni Battista Avellone exemplified this mindset in a 1912 open letter, decrying cinema as ‘an enormous, crowded, and very attractive school of immorality and perversion’. He argued that,

The political authorities must fully carry out their duty to oversee public spectacles and to come to the defense of public morality, rigorously and without fail, preventing the depiction of immoral acts, and seizing films to prevent their circulation”

The result was a system of pre-screening and approval, with films scrutinised for content deemed offensive to morals, national dignity, or public order. These early censors wielded their scissors with zeal. Sexuality was a primary target, with even the mildest suggestion of impropriety often excised. Political content also faced intense scrutiny, as anything perceived as challenging the established order risked rejection.

The impact was immediate, explains Roberto Curti. In the eleven months following the 1913 law, 3,979 films were examined, with 46 rejected outright and 128 passed only after cuts. Even innocuous scenes fell victim to the censor's paranoia. In one notable case, a scene from "Mrs. Tutti Frutti" (1921) featuring a girl in a swimsuit on a swing was deemed too provocative and removed.

North America

Across the Atlantic, conservatives were equally panicked. Profit-driven movie makers were corrupting the masses, leapfrogging the traditional controls of clergy, teachers and family. Wittern-Keller (2013) explains that in the Progressive Era, movies were not necessarily seen as legitimate vehicles of free speech. Progressives often welcomed censorship to maintain moral order.

Right across Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New York, state legislatures and city councils established local censorship boards. Statutes strictly proscribed anything ‘indecent’, ‘immoral’, ‘obscene’ and ‘sacrilegious’. So much for the First Amendment!

Catholic leaders formed a mass-membership organisation - ‘the Legion of Decency’ - and threatened Hollywood with a nationwide boycott unless they produced films that were family-friendly. Fearing federal censorship, movie moguls cowed.

Even when distributors fought government censorship, none invoked their right to free speech or claimed constitutional violations. The meaning and interpretations of a historic document was actually subjective, varying considerably over the past century. Only in 1925 did the Supreme Court declare that free speech is a protected ‘liberty’.

Canada

In 1911, Ontario introduced a censorship law for moving pictures.

Though, as Pierre Véronneau details, this wasn’t accepted uncritically. As shown below, a local newspaper bit back.

Germany

Conservative groups in Germany were similarly alarmed by cinema's perceived threat to public morality. Martin Loiperdinger explains that they viewed film as a dangerous medium that could corrupt the masses, especially youth, by depicting violence, crime, and sexuality. Moral panic was a primary driver of early censorship efforts, with authorities and self-appointed guardians of public virtue seeking to dictate what could be shown on screen.

Political concerns were equally significant. As cinema's power to shape public opinion became apparent, authorities grew increasingly wary of its potential to challenge the established order.

During the Weimar Republic, censorship often targeted films that were perceived as threatening to "public safety and order" or undermining "Germany's reputation and standing." This broad mandate allowed censors to suppress content that questioned political leadership, criticised institutions, or portrayed social conflicts.

The case of Sergei Eisenstein's "Battleship Potemkin" (1925) exemplifies this political censorship. Despite initial approval, the film was ultimately heavily cut and temporarily banned due to fears that it might incite revolutionary sentiments. Scenes of violence against authority figures were systematically removed.

Mexico

Battling Foreign Stereotypes and Moral Corruption

As a relatively poor country with a nascent film industry, Mexico faced an influx of foreign productions. In 1919, a mere 2.2% of releases were Mexican, 26% were Italian and 58% were American. Many were pejorative.

So, I pose this question to my readers:

If you were a Mexican official in the 1910s and 1920s, would you censor films that promoted negative stereotypes about your country and its people?

Protecting National Image

Hollywood's depiction of Mexican history was particularly contentious. For instance, Cecil B. DeMille's "The Woman God Forgot" (1917) faced heavy criticism for its inaccurate portrayal of historical figures like Montezuma and Cuauhtémoc. As detailed by Francisco Peredo-Castro, the Mexican government viewed censorship as a "necessary evil".

The situation reached a boiling point in 1922 when the Mexican government temporarily banned all Paramount, Goldwyn, and Metro movies. Hollywood then got scared, fearing a potential ban across all Latin American markets.

In response, the newly-created Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) promised not to produce films that presented Mexican characters in a "derogatory or objectionable manner." This agreement extended across Latin America.

Religious Concerns

Mexico also grappled with concerns over public morality. Catholic organisations, such as the Mexican Legion of Decency and the Knights of Columbus, exerted significant influence over film censorship. Cuts and bans were imposed on films deemed sacreligious:

Fernando de Fuentes's "Creo en Dios" (I Believe in God, 1940) had its ending changed due to religious pressure.

José Díaz Morales's "Jesús de Nazareth" (1942) and Julio Bracho's "San Felipe de Jesus" (1949) faced cuts in scenes depicting temptation.

Gabriel Retes's "Nuevo Mundo" (The New World, 1976) was censored for demystifying the "apparitions" and "miracles" of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Films addressing the sexual lives or crimes of Catholic clergy were particularly problematic. Notable examples include Arturo Ripstein's "La Viuda negra" (The Black Widow, 1977) and Carlos Carrera's "El crimen del padre Amaro" (Father Amaro's Crime, 2002).

Late into the 1980s, censorship persisted. Jean-Luc Godard's "Je vous salue, Marie" (Hail Mary, 1985) and Martin Scorsese's "The Last Temptation of Christ" (1988) were both banned for over a decade before finally being released in limited circulation.

The lesson from Mexico’s cinematic history is that pressures for censorship are not necessarily aligned with top-down repression or religion. Controls may also emanate from desire to protect progressive values: namely the dignity of a poorer post-colonial society.

1930s-1940s: Empires & Propaganda

Singapore and Hong Kong

The British colonial authorities saw cinema as a powerful medium that could potentially stir unrest. As a result, they implemented censorship in their colonies.

In Singapore, censorship was particularly stringent. By 1938, censors were increasingly banning films for political reasons, propaganda, or war-related content. Over time, bans on American films decreased, those on Chinese films increased, reflecting growing political tensions. The censors banned numerous Chinese and Hong Kong films, including "Midnight Vampire" (1936), "The Lady Pirate" (1937), and "War at Eastern Front" (1938).

Hong Kong's censorship became stricter by the mid-1930s, particularly regarding politically sensitive subjects. This shift coincided with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1934, leading to bans on scenes depicting warfare in China.

India

In colonial India, films were censored to block access to communist or social ideals, limit exposure to notions of freedom (from the US), and prevent the emergence of nationalism. By restricting access to revolutionary ideologies and nationalist sentiments, the British aimed to maintain their grip on power.

V-Dem rightly depicts strong government censorship in early 1900s Hong Kong and India.

Interwar Period: Totalitarian Propaganda and Democratic Dilemmas

Italy’s Fascist Era (1922-1943)

‘Cinema is the strongest weapon’ - declared Mussolini, as he established state-run film schools and production companies. Films glorifying the regime were encouraged, while those exploring social issues or critiquing authority faced severe restrictions. The 1923 regulations explicitly targeted content that could ‘disturb public order’ or offend ‘national prestige’.

V-Dem suggests that while the US and Italy had previously seen similar levels of censorship, controls now tightened on par with contemporary Egypt.

Public officials and institutions could only be portrayed positively. Hints of state corruption or incompetence was ruthlessly crushed.

Censors also targeted content that might incite ‘class hatred’ or challenge the established social order. Films addressing social inequality or labour struggles often faced significant cuts or outright bans.

Curti offers several examples:

King Vidor's "Peg o' My Heart" (1922) had all references to the Irish revolution removed;

Cecil B. DeMille's "Triumph" (1924) saw scenes of workers striking against an unfair factory owner excised.

Social critique was silenced, as cinema reinforced reinforced fascist supremacy.

The USSR

Right after the 1917 revolution, Lenin declared cinema was “the most important of the arts”. Ever since, it has continued to play a major role in totalitarian propaganda.

Soviet authorities oversaw the entire production process, explains Richard Taylor. ‘Thematic plans’ (templany) were introduced for each studio, outlining pre-approved subjects; then all scripts were scrutinised for conformity. After production, Stalin would provide direct feedback on films, in late-night Kremlin screenings.

What was prohibited?

Films addressing social inequality or labour struggles often faced significant cuts or outright bans. Mental illness and suicide, caused by unemployment or starvation, were absolutely prohibited. Any hint of "class hatred" that didn't conform to the official narrative was censored. Sergei Eisenstein's "Bezhin Meadow" (about a farm boy whose father wants to betray the government, 1935-1937) was remade 14 times before being ultimately banned.

Wartime US

During World War II, the US Bureau of Motion Pictures encouraged Hollywood to support the war effort and boost morale! So this wasn’t censorship, but rather a national endeavour. Movie makers generally cooperated, such as by showing allies positively (Wittern-Keller 2013).

As a Brit, let me say, thank you Hollywood! ;-)

1950s-1960s: Cold War Cinema

Italy

The fall of fascism did not immediately herald a new era of cinematic freedom, details Curti. Censorship structures remained in place, now wielded by Christian Democrat politicians deeply influenced by Catholic morality. Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, who would later become President of Italy, was particularly zealous in his efforts to ‘protect’ Italian audiences from perceived immorality.

Scalfaro laid out a strict ‘moral code’ for films, insisting that it was ‘not admissible that the ideal of homeland is debased and humiliated in films’ and that ‘it is also necessary to respect the moral of the family, a human principle even more than a Catholic one’. This led to significant editing, explains Curti. Italian characters in foreign films portrayed negatively were given different nationalities!

Hollywood classics were not immune. John Ford's ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ (1940) languished for years before its Italian release in 1952. When it finally reached screens, it was heavily edited and dubbed to remove political content. Ma Joad's stirring final monologue about the resilience of the common people was cut entirely. Tom's iconic line, ‘Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there’, was sanitised to:

‘Wherever there's a man fighting for his kids I'll be there.

Wherever humanity tries to elevate itself, I’ll be there.’

In the 1950s, the board demanded cuts to scenes considered ‘offensive to the decorum and prestige of police officers’, effectively crushing social critique. Any portrayal of authority figures in a negative light was systematically removed.

Satire and Resistance

Still battling with censors, Curti details how Italian filmmakers turned their wits and creativity towards satire. This resistance through art is perfectly exemplified by Giorgio Bianchi's satirical comedy "Il moralista" (The Moralist, 1959).

The film starred Alberto Sordi as Agostino, the seemingly upright but obtuse secretary of a self-styled Morality Union, fighting against all manner of perceived vices. This character was a thinly veiled caricature of real-life Christian Democrat politician Agostino Greggi, known for his zealous moral crusades. Bianchi's film mocked the censors, portraying them as hypocritical, corrupt, and ultimately more despicable than the 'immoral' elements they sought to suppress.

The irony was not lost on the censorship board, explains Curti. "Il moralista" received a V.M.16 rating (forbidden to those under 16), ostensibly because

‘the unhealthy environment in which all the action takes place can affect negatively the soul of young people’.

Despite numerous cuts and changes, the rating was upheld on appeal and even increased to V.M.18.

Federico Fellini, another giant of Italian cinema, joined the fray with his episode "Le tentazioni del dottor Antonio" (1962). This segment centred on another morality-obsessed citizen, even recreating a famous real-life incident where politician Oscar Luigi Scalfaro slapped a woman for wearing a low-cut dress in public.

McCarthyist US

The United States, often celebrated as a beacon of free speech, has not been immune to periods of intense censorship. One of the most notorious examples is the era of McCarthyism in the 1950s, named after Senator Joseph McCarthy. This period saw widespread accusations, blacklists, congressional hearings, and loyalty oaths aimed at rooting out supposed communist sympathisers.

Hollywood, with its immense cultural influence, became a prime target. In 1947, ‘The House Un-American Activities Committee’ (HUAC) launched a major investigation into the motion picture industry. They summoned 41 writers, directors, and producers to testify about alleged communist infiltration. Ten of these individuals, who became known as the 'Hollywood Ten', refused to cooperate, invoking their First Amendment rights. As a result, they were legally convicted, jailed, and blacklisted by the studios.

This witch hunt had a chilling effect on the entire industry. Many progressive filmmakers found themselves suddenly unemployable. Others, fearing similar repercussions, began to self-censor. The result was a dramatic shift in the content of American films. Producers and writers steered clear of controversial themes, opting instead for safer, more conservative narratives.

Hui Ren Tan and Tianyi Wang find that McCarthyism’s impact went well beyond those directly accused. Hollywood became much more conservative.

Moreover, this change in film content appears to have had tangible effects on public opinion. Counties with higher exposure to these more conservative films showed increased support for Republican candidates in subsequent elections. This demonstrates the power of cinema not just as a reflection of society, but as a force capable of shaping political attitudes.

Moral Policing

McCarthyism was just one element in a broader landscape of moral policing in 1950s American cinema. The Production Code Administration justified many forms of censorship.

After WWII, US distributors tried to import daring, controversial Italian movies (such as Roma città aperta, Ladri di biciclette, and Riso amaro), yet faced restrictions.

The US public was ideologically divided. American Catholics were deeply aggrieved by the 40-minute Italian film titled Il miracolo (The Miracle, 1948), and New York’s Archbishop successfully lobbied state authorities to recant its license.

Unable to stomach lost revenue, these small businesses sued. Media companies wanted to make money by capitalising on public demand. As a result, they lobbied for freedoms! Frustrated by cuts and bans, Howard Hughes challenged New York censors, invoking his right to free speech!

Legal scholars were divided. In an antitrust case, Justice William O. Douglas declared:

“We have no doubt that moving pictures, like newspapers and radio, are included in the press whose freedom is guaranteed by the First Amendment (1948).

By contrast, Charles Desmond (Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals) maintained that democratically-elected governments were right to censor and prevent evil:

“Facile writers follow current fashion, but detour around logic and history when they deny to censorship any place in democratic governmental processes, and describe all censorship as repressive and tyrannical interference with freedom to express ideas.

Freedom ultimately prevailed. Shaking off its censor board, an Ohio court declared it “repugnant to the sacred Bill of Rights”.

Post-War East and West Germany

Under Nazi rule, cinema was eyed as a powerful tool of propaganda, with Goebbels declaring it "the strongest weapon."

In the post-war period, both East and West Germany continued to use censorship as a means of cultural control, albeit in different ways. In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the state monopoly on film production allowed for direct control over content. Films were expected to conform to socialist principles and promote the state's ideology.

In 1965, 12 films were banned. Notable among these were "I Am the Rabbit" (1965), which questioned the principle of "Party loyalty," and "Trace of Stones" (1966), which critiqued bureaucratic incompetence. These films weren't shown in East Germany until after reunification in 1990.

West Germany, despite constitutional guarantees against censorship, found other ways to control film content: state subsidies! The Film Funding Act of 1967 allowed for the withdrawal of funding if a completed film offended moral or religious sensibilities or contravened the constitution.

Producers, distributors, and cinema owners were effectively prohibited from dealing with films not approved by the FSK (Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft), facing potential financial ruin if they tried to circumvent this system. This economic pressure effectively discouraged filmmakers from producing anything too critical.

The FSK's decisions were shrouded in secrecy: neither the number of objectionable titles nor the grounds for objection were made public. Drawing on the cases that have since come to light, Martin Loiperdinger reveals that Cold War politics heavily influenced censorship. Films from Eastern bloc nations faced particular scrutiny. The introduction of the Impoundage Act in 1961 gave legal basis to these import controls, explicitly outlawing films that might function as "propaganda against the free democratic order." The Czechoslovak production "A Higher Principle" (1960) was impounded because its depiction of Nazi violence in occupied Prague was perceived as "a threat to Germany's reputation and standing."

The FSK also sought to instil trust and national pride and trust - even to the point of interfering with narratives about Germany's Nazi past. In 1963, the FSK's ruling on Vittorio de Sica's "The Condemned of Altona" (1962) caused significant controversy. The censors demanded the removal of dialogue referencing German companies like Flick, Krupp, and Mercedes-Benz in connection with Nazi crimes. They also objected to lines criticising the current existence of the Federal Army.

West German filmmakers, aware of the potential financial risks, often self-censored, avoiding topics or treatments that might run afoul of the FSK or jeopardise state funding.

Communist China

Initially, the new Communist government briefly abandoned film censorship, believing that the new China should be more democratic and liberal. But this period of openness was short-lived, explains Zhiwei Xiao. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 triggered fears, leading to a tightening of media restrictions.

The state’s growing capacity and monopoly on film production allowed for greater oversight and enforcement. Filmmakers, aware of the risks, often self-censored. Unlike in the Nationalist period, where filmmakers might play "cat and mouse" games with censors, few under the Communist regime dared to take such risks.

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) marked an extreme period of censorship. Not only were all pre-1949 films banned, but so too were the majority of films produced during the communist rule after 1949. These were condemned for being insufficiently revolutionary, undermining class struggle, glorifying bourgeois individualism, or opposing Mao's thought.

Film production nearly halted during this period. Between 1966 and 1973, no feature films were produced. From 1973 to 1976, only about three dozen films were made, with only a third actually released for public screening. The few films produced were tightly controlled.

Filmmakers themselves became targets, details Zhiwei Xiao. Many directors, actors, and technicians were subjected to purges or detention. The authorities also introduced a new form of censorship: nationwide campaigns to criticise and condemn specific films, manufacturing public opinion against works deemed politically incorrect.

After Mao's death, the criteria for censorship shifted. In 1981, the Ministry of Radio, Film and Television (MRFT) issued guidelines prohibiting content deemed "injurious to national unity, sovereignty, and territorial integrity; undermining national security, honor and interests; promoting separatism and causing damage to ethnic unity; leaking or revealing state secrets; racy images, superstitious messages, and violent acts." The regulation explicitly stated that “unscientific” and “superstitious” contents in films will not be tolerated. Authoritarian rulers thus harnessed cinema to forge national unity, pride and loyalty.

1960s-1970s: Celluloid Nation-Building

Turkey

If citizens doubt the state’s efficacy, they may turn to alternatives - such as family or religion. Tackling this challenge, the Turkish government of the 1960s and early ‘70s used cinema to champion secularism and strengthen confidence in state institutions.

Strengthening confidence in the state

Censors insisted that criminals must always be apprehended by the police and face legal consequences through the justice system, explains Dilek Kaya Mutlu. “Fantoma, Let’s Meet in Istanbul” (1968) was permitted on the strict condition that criminals were caught by the police. Criminals were not even allowed to die before facing legal punishment.

Depictions of honour killings and vigilante justice were strictly prohibited. Cinema was thus a crucial component of nation-building, reinforcing the message that the state held a monopoly on justice.

Police and soldiers were always shown as upstanding - with regulation haircuts and uniforms, adhering strictly to official standards. These figures of authority could never be shown engaging in behaviour deemed immoral or unprofessional. Smoking, drinking, flirting, or any hint of romantic entanglement was strictly forbidden for characters in uniform. The commissions demanded that law enforcement treat individuals with utmost respect, prohibiting any depiction of insults, brute force, or corporal punishment.

In traffic accidents or fire scenes, police had to be shown investigating the cause, further reinforcing the image of an efficient and orderly society where the state was always in control. Dilek Kaya Mutlu explains that this sanitised portrayal was a deliberate attempt to cultivate public trust in these institutions.

Secularism

Historical religious films were allowed, but these were only allowed to align with beliefs of the Sunni majority (not Alevis).

Movies on contemporary life were strictly secular. Censors rejected visuals of namaz (ritual prayer), the sound of ezan (call to prayer), and any references to the Quran in contemporary settings. Scenes showing imams or hocas (mosque clerics or preachers) were routinely cut, as were depictions of religious marriage ceremonies (imam nikâhı).

Folk or unofficial Islamic practices were consistently censored in both historical and contemporary settings. Depictions of saint veneration, pilgrimages to shrines, rain prayers, amulets, spells, and miracles were rejected as exploitative of religious feelings or harmful superstitions. References to religious orders and brotherhoods (tarikats), which had been outlawed since 1925, were strictly prohibited. This stance reflected the state’s determination to eliminate alternative sources of religious authority that could challenge the national regime.

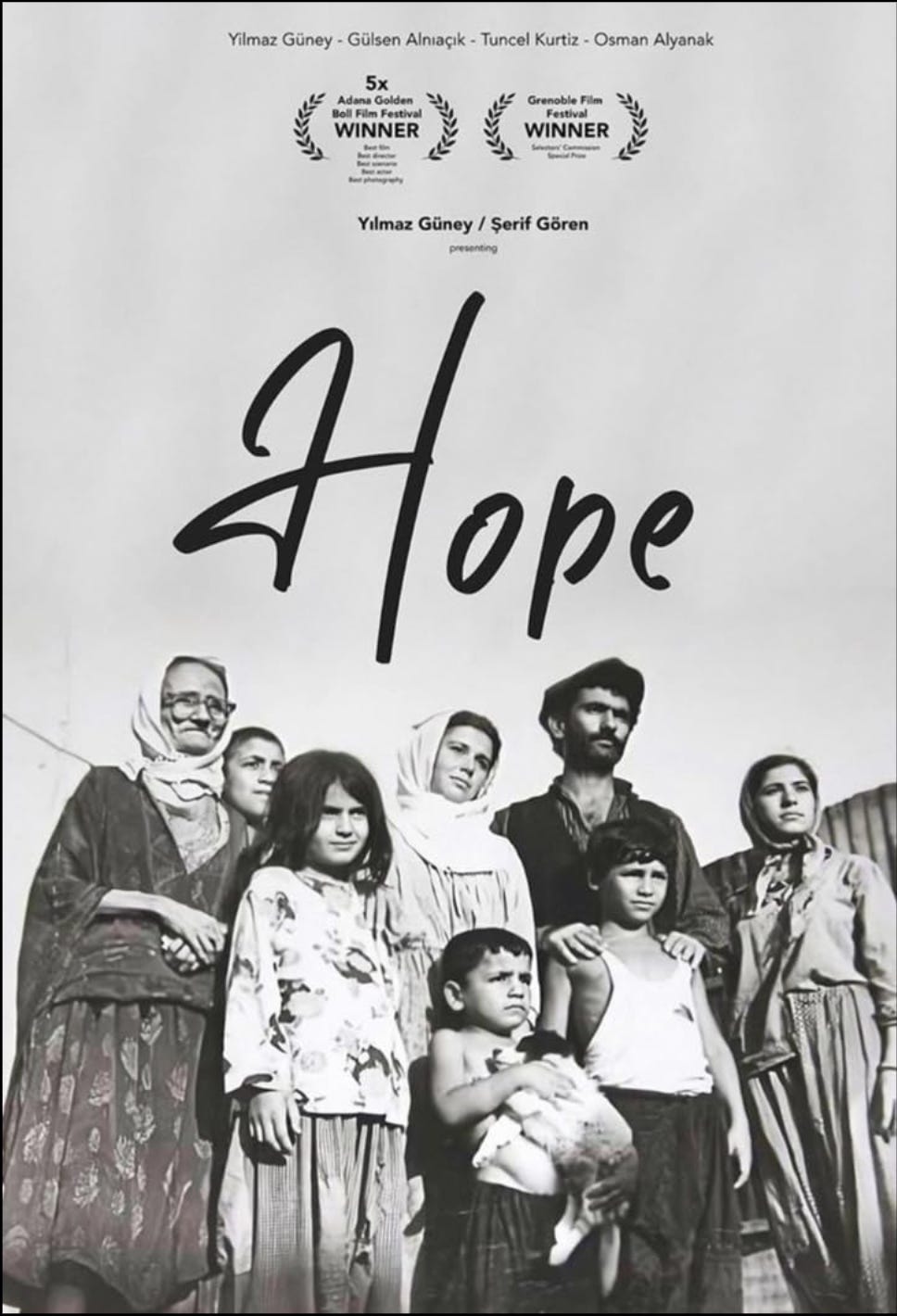

The censors’ approach shifted slightly in 1970, as evidenced by two contrasting cases. Yılmaz Güney's "Hope" (1970) was banned for allegedly ridiculing religious worship and functionaries, despite its critical portrayal of superstition. In the same year, "Uniting Roads" (1970), which promoted an Islamic way of life in modern Turkey, was accepted despite concerns about religious propaganda. This shift indicated the state's growing concern about the rise of leftist movements and a tentative consideration of Islam as a potential counterbalance.

Turkish film censorship thus served as a means of constructing a national identity and reinforcing state authority. By controlling cinematic narratives, the government sought to shape public perception, promote secularism and centralise power.

Italy: 1960s

Under Italy’s centre-left governments (1963-68), there was a perceived loosening. Seizing this opportunity, Italian movie makers lobbied to overturn censorship.

Yet, their calls were frustrated.

Twice a week, censors continued to gather at the Ministry headquarters, each meeting lasting two hours as they meticulously combed through films for any hint of immorality. While outright bans became less frequent, Curti details that many films were still heavily cut before being approved.

"La donna nel mondo" (Women of the World), a documentary which explored the condition of women around the globe, was rejected twice by censors who objected to “the vulgar aspects of sex”. In truth, the film’s content was rather diverse, featuring a female minister conducting mass in Sweden to women working dangerous diving jobs in Japan, and even powerful women in American finance. The film also touched on taboos like homosexuality and prostitution.

Some Italian filmmakers were nevertheless defiant! Throughout his life, Pier Paolo Pasolini (left-wing intellectual and openly homosexual) underwent trial thirty-three times for his literary and film work, continually pushing for artistic freedom.

Bernardo Bertolucci's “Last Tango in Paris” (1972) epitomises the tensions of this era. Initially approved for release, the film was quickly banned after just five days in cinemas. Its copies were ordered destroyed, and its creators, including stars Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider, faced criminal charges for obscenity.

The ensuing legal battles and public debate highlighted political contestation. The court’s ruling deplored the film's ‘confused provocatory ideas which tend to the destruction of traditional social values’. Bertolucci shot back, calling it ‘a reactionary, fascist verdict’. Film critic Giovanni Grazzini lamented,

Chile: Censorship as Religious Reward

In 1973, General Pinochet seized power in Chile, ushering in an era of authoritarian rule marked by severe human rights violations. Facing criticism from the mainstream Catholic Church, Pinochet sought to maintain legitimacy by courting conservative Catholic organisations such as Opus Dei and Tradition, Family and Property (TFP).

These religious conservatives had long advocated for moral censorship. Pinochet obliged by reforming the Council for Cinematic Classification (CCC) with a mandate to censor films that "run contrary to public order, morality".

Jane Esberg's research, analysing thousands of film reviews and censorship decisions, reveals that after the coup, censorship dramatically increased. Films containing sexual content were 11% more likely to be censored. Censors' notes often highlighted "scenes with lesbianism" or "grotesque humour" as reasons for censorship.

This strategy of "censorship as reward" proved effective in securing religious support for the regime. In 1987, Pope John Paul II visited Chile and gave Communion to Pinochet, a significant show of legitimacy for the dictator.

The fall of the dictatorship and subsequent democratisation saw censorship rates drop by 50%, underscoring how tightly moral censorship had been tied to the authoritarian regime's need for religious legitimacy.

The Chilean case demonstrates how authoritarian regimes can use moral censorship not just as a tool of repression, but as a means to cultivate support from conservative religious factions. It provides a stark contrast to examples like Turkey, where censorship was used to promote secularism, highlighting the diverse motivations behind cinematic control.

1980s-2000s: Loosening Reels

US

US regulation evolved to a system of ratings. Upon signing their picture deals, directors agree to deliver a film as a G, PG, PG-13 or R, then do whatever it takes to satisfy CARA. West Germany also moved to a system of age ratings.

Testing the limits of permissibility, South Park creators pursued a strategy of shock and awe - as revealed by a leaked set of memos. In 1999, the CARA board asked them to change the dialogue from “God fucking me up the ass” to “He’s the biggest bitch of them all.”

Curiously, even though censorship has relaxed, sex on screen has actually plummeted. What’s going on? Are actors demanding steeper prices for nudity, is the US public increasingly prudish, or are audiences getting their highs elsewhere (PornHub)?

Ireland

Over the late 20th century, Ireland has undergone massive cultural liberalisation.

Back in 1923, the Censorship of Films Act 1923 empowered censors to ban or cut films deemed "indecent, obscene or blasphemous" or "contrary to public morality." Between 1923 and 1965, 2,500 films were banned, while 10,000-12,000 saw cuts.

Early censorship was driven by a conservative Catholic-nationalist alliance, aiming to protect traditional family values and shield Ireland from foreign influences. Kevin Rockett notes that the first censor, James Montgomery based his decisions on the Ten Commandments

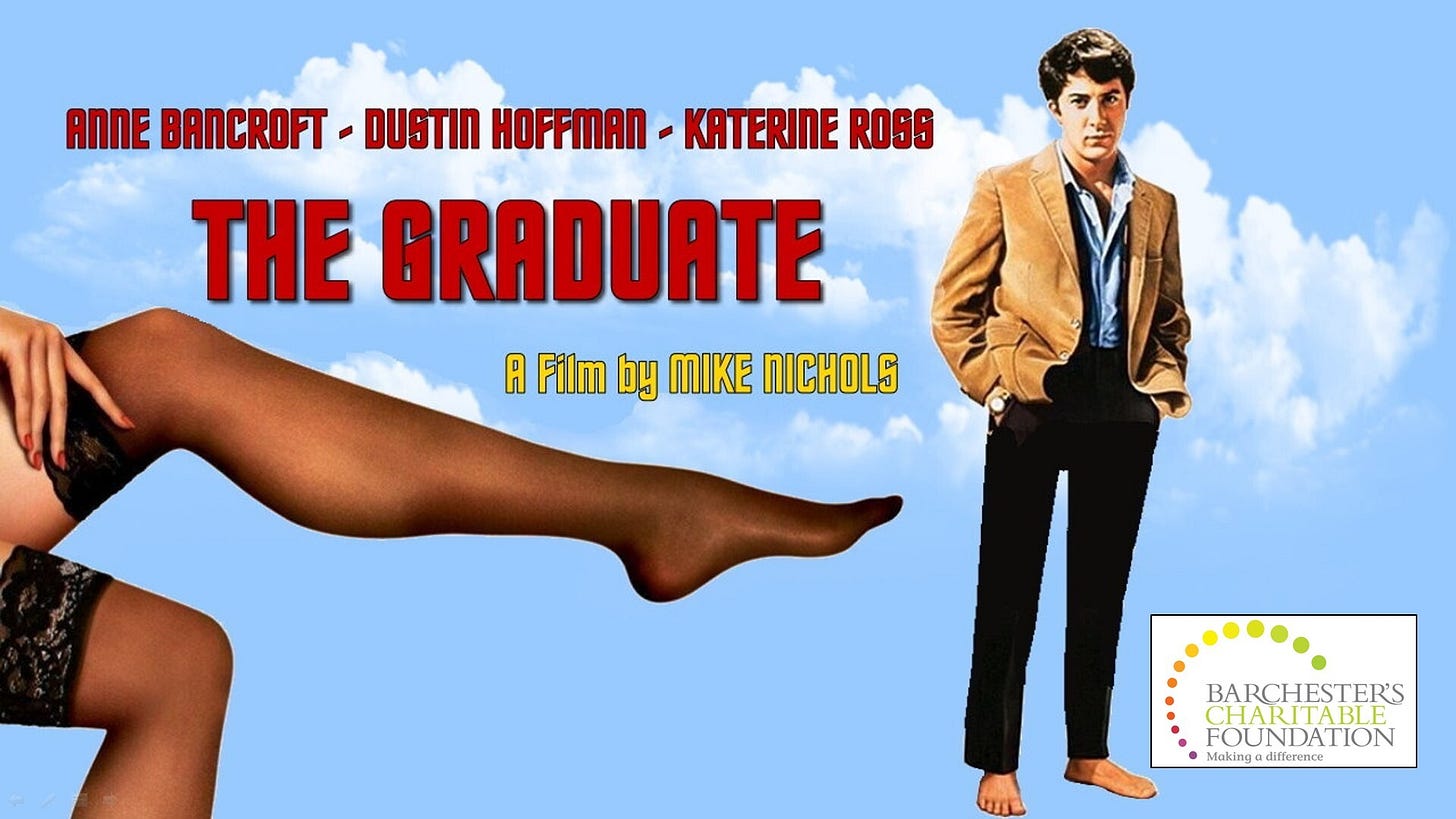

Active censorship persisted in the 1960s. "The Graduate" (1967) was passed with an over-18 certificate but only after 11 cuts that significantly altered the film's narrative.

By the 1990s, Irish film censorship was largely in line with other Western countries, except for its stricter stance on pornography. The state shifted to classification, reflecting a shift from moral policing to providing consumer information.

Italy

Fast-forward to 2021: Italy officially abolished its film censorship law. Thanks to ongoing cultural liberalisation, state intervention in the arts was finally over.

Cinecensura (an online exhibition promoted by the culture ministry) states that since 1944, 274 Italian films, 130 American movies and 321 from other countries have been censored. 10,000 have been modified.

2000s-Present: Religious Mobilization in the Digital Age

Nigeria

For Northern Nigeria, cinema has became a battleground for competing visions of Islamic identity and morality. The Hausa film industry, centred in Kano (hence Kannywood), grew rapidly in the 1990s. But it faced criticism from religious leaders who saw the films as un-Islamic.

Upon the release of "Saliha?" (1999), a film about a girl who wore the hijab as a sign of virtue but was revealed to have had premarital sex, a religious group in Kaduna issued a fatwa (religious ruling) calling for a death sentence on the director and producer. The group demanded the film be removed from the market and that the filmmakers apologise to the Muslim community.

Another film, "Malam Karkata" (Twisted Teacher, 1999), which depicted a corrupt religious leader demanding sexual favors in exchange for spiritual guidance, faced such strong opposition that marketers refused to stock or distribute it. These incidents highlight the tension between filmmakers seeking to expose societal hypocrisy and a public that views such portrayals as disrespectful to Islam.

Censorship intensified following the implementation of Shari'a law in 2000, and the introduction of the Kano State Censorship Board (KSCB). The appointment of Abubakar Rabo Abdulkarim as head of the KSCB in 2007 marked a particularly strict period. Rabo imposed new regulations, including banning married women from acting and requiring all women in the industry to have a male guardian, who had to sign a document accepting liability for her rule-breaking. Rabo also banned singing and dancing.

Filmmaker Adam A. Zango was imprisoned for three months in 2007 for releasing an uncensored music video. Popular comedian Rabilu Musa (Ibro) was also jailed for allegedly releasing an uncensored film compilation. These harsh measures led many filmmakers to flee Kano, relocating to more liberal cities like Kaduna and Jos.

Every society has a diverse mix of progressives and conservatives, pushing for ideological dominance. Northern Nigeria fits this trend. Subversive musicians have composed satirical songs mocking the censors, shared on mobile phones. Films also exposed the hypocrisy of outwardly pious elites, such as Saeed Selbar's "Kyalli" (2010), which depicted a moralistic politician having an affair with an actress. In 2010, Rabo himself was caught in a compromising situation with a young woman. This scandal, along with political changes, led to a relaxation of censorship by 2011.

Northern Nigeria is thus a great example of how religious organisations may lobby for stricter controls, while politicians seek to gain legitimacy by harnessing the power of the state to entrench religosity, even if some portion of the public is unconvinced.

Malaysia: The Rise of Participatory Censorship

Between 2010 and 2022, Malaysia recorded the highest number of censorship violations in Southeast Asia, with 245 documented cases.

Malaysia's censorship practices are heavily influenced by its ethno-religious dynamics. Given the rising popularity of jurisprudential Islam, politicians have increasingly cloaked themselves in religion to gain legitimacy.

Demands for censorship may come from citizen mobilisation, organising for bans and boycotts.

A prime example of this phenomenon is the controversy surrounding the 2019 telefilm "Demi Tuhan Aku Bersaksi" (I Swear to God). Produced by the national broadcaster Radio Televisyen Malaysia (RTM), the film tells the story of a transgender person who enrolls in an Islamic boarding school to become a better Muslim. Despite passing the official Censorship Board, the film sparked outrage when its trailer was released online. The image of the main character appearing to "offer his bottom to another man" led to protests from Islamic organisations. Screening was delayed by a year, after securing support from the Federal Territories Mufti.

“Tiger Stripes” (following a rebellious girl who gets her period) was submitted to the 2024 Academy Awards, but on the condition that ‘inappropriate’ scenes were cut for local audiences. Khoo Gaik Cheng, an expert on Malaysian cinema, attributed this to politicians using ethno-religious identity, “and it’s always Muslim because they’re the loudest bloc”.

In a sense, censorship is increasingly ‘democratised’, in so far as religious groups can freely mobilise and then secure government restrictions.

Netflix and Censorship

With the rise of instant personal entertainment, battles for cultural control are now shifting to streaming platforms. As Netflix seeks to capitalise on emerging markets, it faces repeated pressures for censorship.

Defiant, the streaming giant has sometimes leveraged local institutions to champion cultural liberalisation. Challenging a Brazilian judge’s request to remove a satirical film showing Jesus as a gay man, Netflix filed a complaint at the Supreme Court.

Censorship demands have been especially strong in the South-East Asia - accounting for over the half the films that Netflix recently agreed to block. Censorship requests vary, and include portrayals of drug use, LGBT and sovereignty over the South China Sea.

Hollywood and China’s Partnership

By the 2000s, Chinese films had to pass through multiple checkpoints: initial script filing during development, content review during post-production, technical censorship of the final cut, and a final ‘dragon seal’ approval. This multi-stage system allowed the state to shape films throughout their creation.

Censors often avoided written documents in favour of verbal feedback, making their requirements harder to track or challenge. Success in this environment depended heavily on what industry insiders called ‘back channels’ - informal relationships between filmmakers and censors built through years of social interaction (‘guanxi’).

U.S. studios - eager to break into the Chinese domestic market - learned to self-censor proactively. “We didn't break any of those rules because we knew what the rules were” one producer noted. “You don’t talk about the government; you stay away from any sensitive topics”.

By the late 2010s, China had developed a new genre dubbed ‘New Mainstream’ - big-budget commercial films that blended high production values with patriotic messaging. The 2017 action film Wolf Warrior 2 exemplified this trend, becoming China’s highest-grossing film by appealing to nationalist sentiment while matching Hollywood production quality.

MBS’s Netflix and Change

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has embarked on an unprecedented experiment in top-down secularisation, leveraging media and entertainment to drive cultural change. This strategy appears to be addressing a complex trilemma:

Boosting economic legitimacy,

Mitigating potential attacks from religious conservatives, and

Limiting dissent to maintain control.

A key player in this cultural shift is Shahid, a Saudi state-owned streaming platform. Shahid offers valuable insights into the kind of society the House of Saud is eager to promote, in state-sanctioned narratives - such as female professional chiefs and musicians.

The Saudi strategy appears to harness the power of storytelling to drive social transformation. By funding and promoting alternative narratives through platforms like Shahid, the state is attempting to make cultural liberalisation appear widely accepted. These stories, presented as glamorous and modern, seek to normalise what was previously unthinkable.

Moreover, for Saudis who were already progressive, these changes may signal permission to openly embrace ideas and lifestyles they had previously kept hidden.

While many countries have used censorship to suppress liberal ideas, Saudi Arabia is using state-controlled media to actively promote more secular and liberal narratives. This approach demonstrates how authoritarian regimes can leverage media not just for repression, but also for driving significant cultural change (echoing 1960s Turkey).

Indeed, MBS’s strategy seems to be working: female labour force participation has doubled.

The Cinematic Tussle

The history of film censorship reveals a constant struggle between different factions of society, each seeking ideological and institutional dominance. We've seen how both progressive and conservative forces have attempted to harness state institutions to shape narratives and entrench their visions.

Cinema has always been seen as a powerful tool for shaping culture;

Diverse groups have wrestled to wield state censorship and propagate their ideology - whether that is religion, nation-building, or authoritarianism.

Resistance not only comes from creatives and liberals, but also profiteering businesses, keen to capitalise on market demand.

Technological innovations may change the stage, but fundamentally humans are always vying for dominance over markets, institutions and culture.

Related Essays

Reel Politics: How the Hollywood Blacklist Changed American Minds

Spain's feminist secret: the backlash against religious authoritarianism & the Almodóvar effect

![The Last Temptation of Christ (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray] The Last Temptation of Christ (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!LXuD!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa44d9524-66be-4796-bb00-e2ed001e1c14_805x1000.jpeg)

Okay but fr, 20th century fighting over books, 21st century fighting our attention spans 😂. For real though, melbet app https://melbet-in.net/en/mobile is kinda that safe space now — it’s got so many game options, it’s impossible to get bored. My friends are obsessed and yeah, I get the hype. It's fun, stress-free, and gives main character energy when you win big. Also, not sure if it’s true, but I keep hearing buzz that Monami Ghosh might be linked with Melbet somehow? Haven’t seen anything official yet, but if true, that’d be kinda big. If you haven’t checked melbet, you’re missing out tbh.