Who Killed the Patriarchy? CCP Radio vs Prestige Bias

In 1970, a young woman in rural China listens to the village loudspeaker. Through the crackle of the airwaves, she hears: ‘Women hold up half the sky!’ This slogan, part of Mao’s campaign for gender equality, was broadcast across the nation. But did these words actually change minds and lives?

At the same time, in her village, she encounters a group of educated urban youth, sent down from the cities as part of the Cultural Revolution. These young women, with their progressive ideas and ambitions, present a living example of greater gender equality.

Which of these forces - the radio broadcasts or the real-life role models - had a greater impact on reshaping entrenched gender norms?

Two awesome studies by Ruoyu Qian and Yi Chen, Ziying Fan, Xiaomin Gu and Li-An Zhou delve into this question, offering a compelling examination of what drives cultural change? Communist China provides a unique testing ground for these inquiries, as it implemented both widespread ideological propaganda and large-scale forced migrations. This combination allows us to compare the relative power of abstract persuasion versus concrete example in transforming cultural attitudes.

Qian’s research reveals the surprising power - and limitations - of communist radio propaganda in reshaping gender norms. Meanwhile, Chen and colleagues uncover the profound impact of the “Sent-Down Youth” movement, which relocated millions of urban educated youth to rural areas.

In this essay, I assess their comparative impact: CCP propaganda versus prestige bias.

Methodology: Riding the Radio Waves

I imagine that when Ruoyu Qian first presented this paper, before even reaching Slide 2, some economist shot up his hand and exclaimed,

“But what about endogeneity? Isn’t radio strength just a function of Communist control or urban density, which might already be more gender equal?”

This is where Qian is very cool. Instead of relying on simple measures of radio ownership, she leverages county-level variation in radio signal strength! But here's the crucial part: she doesn’t use the actual signal strength. Instead, she calculates two measures:

A predicted signal strength based on the actual terrain.

A hypothetical ‘free-space’ signal strength, assuming no geographic obstacles.

By controlling for the free-space signal strength, Qian isolates the variation in signal strength that comes solely from topographical factors – mountains, valleys, and other terrain features that affect radio wave propagation.

Qian uses the Irregular Terrain Model (ITM), a sophisticated tool that accounts for how terrain affects radio propagation. The ITM considers factors like distance from the transmitter, elevation changes, surface reflectivity, and climate conditions. By focusing on this terrain-induced variation, Qian creates a natural experiment. Some areas received stronger signals not because they were more urban or developed, but simply because of random geographic features that happened to be conducive to radio wave propagation!

She combines exposure to radio signals with the intensity of gender propaganda in order to isolate the effects of ideological persuasion through radio, separate from other factors that might influence gender norms. Further, Qian only examines the exogenous variation between places that were otherwise very similar.

Tracking the Tide of Gender Propaganda

Another innovative aspect of Qian’s study is how she quantifies the longitudinal intensity of gender-related propaganda! This is crucial because the strength of radio signals alone doesn’t tell us about the content of the broadcasts. To address this, Qian turns to newspapers.

During the Cultural Revolution, radio content was heavily centralised and closely mirrored the content of official newspapers, particularly the People’s Daily, the mouthpiece of the Communist Party. Qian leverages this relationship to create a proxy for radio content!

Here’s how she does it:

Digitised Corpus: First, she uses a digitised corpus of the People's Daily.

Keyword Search: She then performs a computerised search for specific keywords and phrases: ‘the liberation of women’, ‘gender equality’, ‘women hold up half the sky’, and ‘men and women are the same’.

Density Calculation: For each year, she calculates the ratio of articles containing these keywords to the total number of articles published. This gives her a measure of the intensity of gender-equality messaging for each year.

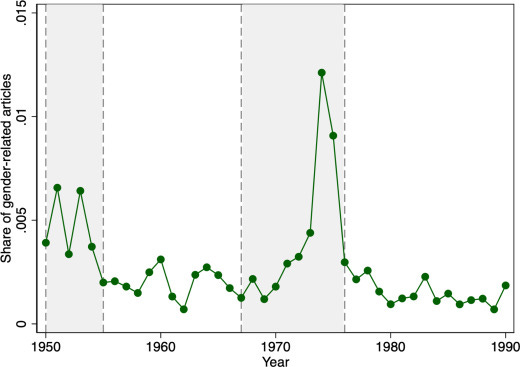

Time-Varying Propaganda Intensity: By plotting this ratio over time, Qian creates a graph showing how the focus on gender equality in official messaging fluctuated throughout the period!

This detailed analysis of propaganda content helps us understand the nature and intensity of the ideological messaging that rural Chinese were exposed to, setting the stage for comparison with the effects of direct exposure to urban youth…

When was propaganda most intense?

There are two clear peaks in gender-equality messaging:

The early 1950s, coinciding with the implementation of the New Marriage Law

The Cultural Revolution, particularly during the ‘Campaign to Criticise Lin Biao and Confucius’ in the mid-1970s

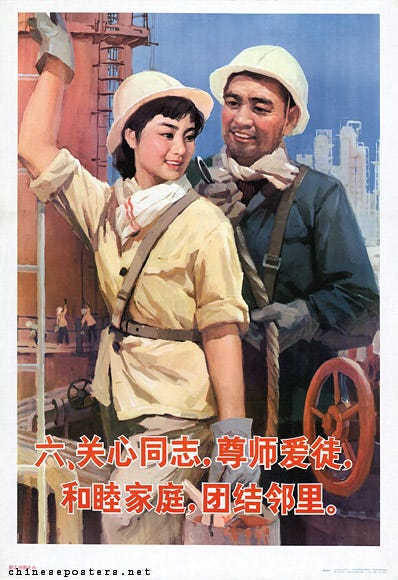

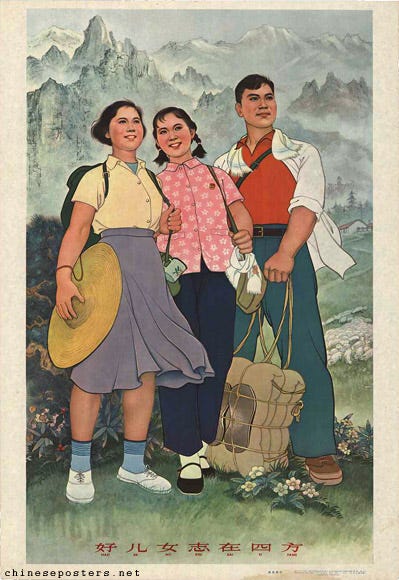

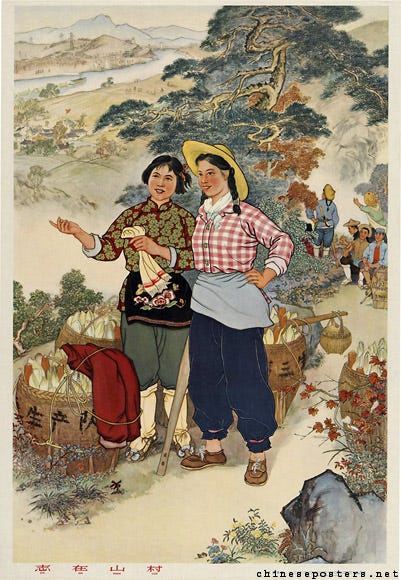

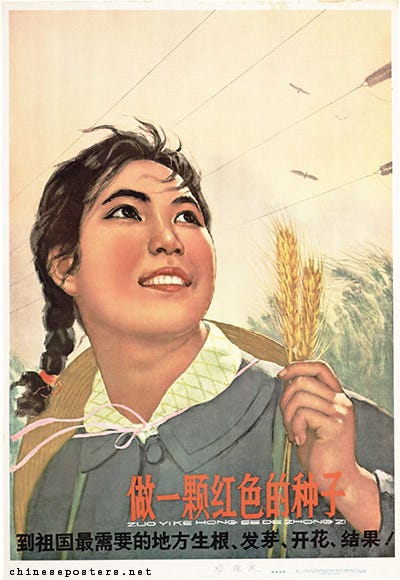

During the Cultural Revolution, the propaganda about women’s roles was particularly intense. Women were portrayed not just as equal participants in economic production, but as militant fighters and political activists. The state media was filled with images and stories of women in traditionally male occupations, challenging long-held gender stereotypes.

Qian then combines this yearly propaganda intensity measure with the geographic variation in signal strength. This allows her to create a weighted average of radio exposure for each county, taking into account both how strong the signal was and how much gender-equality content was likely being broadcast in any given year.

This innovative approach allows Qian to capture not just the quantity of propaganda exposure (signal strength), but also its quality (content related to gender equality)!

The Power of Radio Propaganda!

Areas with stronger radio signals – and thus greater exposure to gender-equality messaging – showed significant improvements in women’s status decades later.

This shows up in terms of

Gender equality in school enrolment and college graduation

Women’s later age of first marriage

Lower fertility

More female employment in high skilled industries.

Gender progressive attitudes.

These effects were even larger in rural areas, with lower literacy.

Caveat: the effects are not huge

A one-standard-deviation increase in exposure only lead to 0.02 increase in the female-to-male ratio of enrolment rates (which is 10% of the SD of this outcome, which has a mean of 72.5%), only raised female age at first marriage by 0.242, and only increased rural women’s high skilled work by 4.1 percentage points.

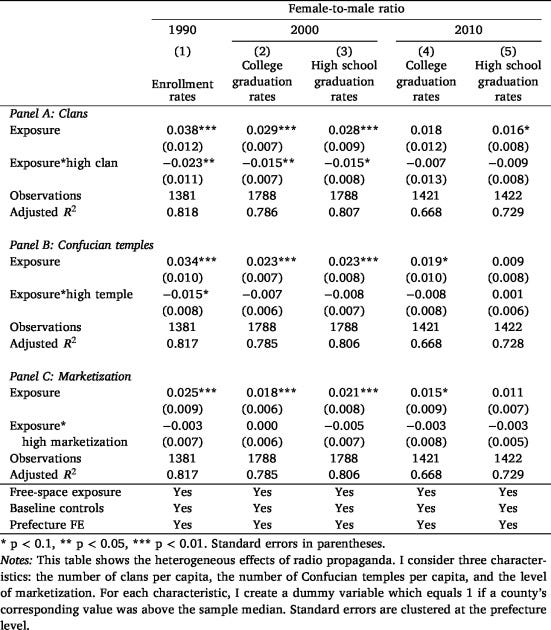

This is partly because Qian deploys incredibly gruelling controls and there is great heterogeneity:

Geographic factors (like elevation and terrain irregularity),

Socio-economic variables (such as population, ethnicity, and economic indicators),

Historical measures (like past gender equality in education)

Prefecture fixed effects in most specifications, effectively comparing counties within the same prefecture, and includes

Controls for potential confounding factors like the presence of sent-down youths and school construction rates during the Cultural Revolution.

Her estimates of radio propaganda’s impact are thus extremely conservative.

While these results demonstrate the power of ideological persuasion, they set up a great comparison with the even stronger effects of the Sent-Down Youth movement, which I will return to.

Please hold your horses/ CCP tractors.

The Confucian Connection

One of the most intriguing aspects of Qian’s findings is that the propaganda was much more effective in areas where Confucian norms were weaker. Evidently, cultural change is much harder where norms are deeply entrenched.

Confucianism, with its emphasis on hierarchy and patriarchy, had been a dominant force in Chinese society for over two millennia. In areas where these norms were strongly entrenched, even intense propaganda struggled to make significant headway.

Qian measures the strength of Confucian norms using two proxies: the number of clans in the area during the Ming-Qing dynasties and the number of Confucian temples. In areas with fewer clans and temples – indicating weaker Confucian influence – the gender-equality propaganda had a much stronger effect. This suggests that new narratives find more fertile ground where competing stories are less deeply rooted.

Non-Persistent Effects!

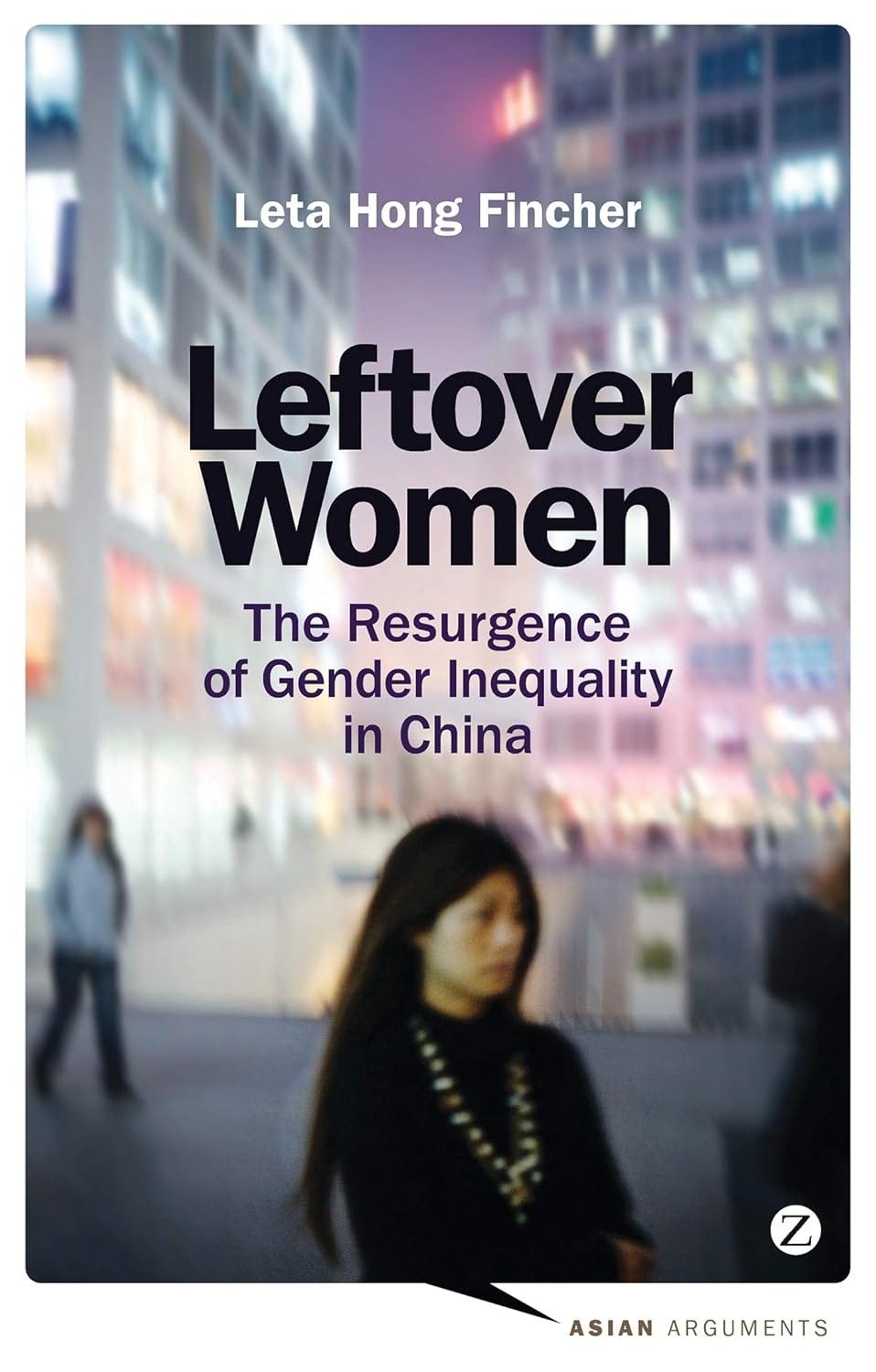

Many of these effects had faded by 2010. This underscores a crucial point:

Cultural narratives are always contested!

Without continued intense promotion of gender equality, patriarchy bit back. The CCP now stigmatises ‘leftover women’, urging them to return home and reproduce - as highlighted by the brilliant Leta Hong Fincher.

Censorship limits women’s capacity to rebut these narratives with feminist films and activism.

The Paradox of Totalitarian Communism

Qian does not say this, but here we see the paradox of totalitarian communism.

While the CCP championed women’s labour force participation, it simultaneously suppressed civic activism. Feminist activism continues to be suffocated. This makes it much harder for women to organise resistance.

In non-communist democracies like Taiwan, Singapore Hong Kong, where feminists and queer activists could mobilise, there has been far greater progress towards gender equality, far higher female political representation, and more tolerance of homosexuality.

The Sent-Down Youth Movement

As part of her controls, Qian examines one of the most significant social experiments of the 20th century: the “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside” movement, commonly known as Sent-Down Youths (SDY).

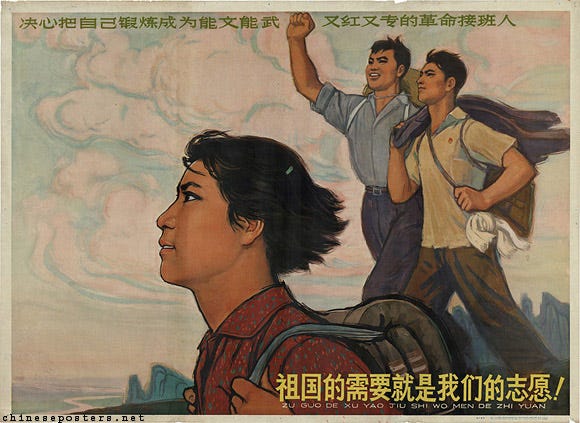

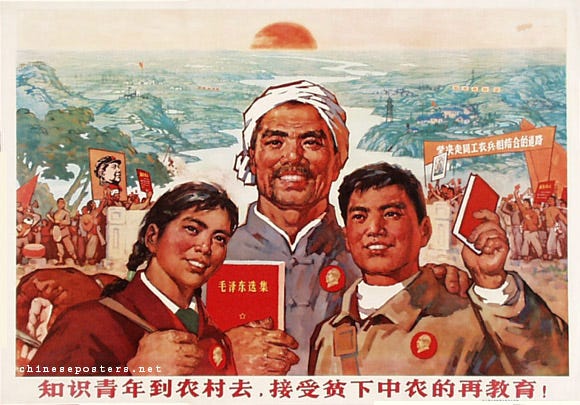

Launched by Mao Zedong in the late 1960s during the Cultural Revolution, this program saw 16 million of urban youth, including high school graduates and young professionals, relocated to rural areas. The official aim was to reduce urban unemployment and to have educated youth ‘learn from the peasants’. It also served as a means of ideological re-education and a way to diffuse revolutionary fervour.

Inadvertently, this programme also increased rural exposure to educated urban women and catalysed an enormous shift in rural gender norms.

Table 5 of Qian’s paper offers a fascinating comparison between these two channels of influence. Sent-down youths had a much stronger effect on gender equality outcomes than radio exposure. For instance, when looking at the female-to-male ratio of enrollment rates in 1990, the coefficient for SDY density (0.747) dwarfs that of radio exposure (0.022). This pattern holds across multiple measures of educational gender equality.

Yi Chen and colleagues, in the American Economic Review, similarly find that China’s SDY movement significantly increased rural girls’ education:

For every 100 SDYs a county received, it would have 36.2 more junior high graduates. The effect on girls was about twice that on boys.

Marriages were delayed among cohorts that received SDYs

Effects persisted 40 years later, on the second generation.

The stark difference in impact between radio propaganda and the presence of sent-down youth underscores the power of direct exposure and personal interactions in shaping cultural norms. The living examples provided by urban youth seem to have left a more profound and lasting impression.

Even when surveyed in 2010, rural residents that received more Sent-Down Youths say that they have more internal control over their circumstances. They believe they can control their fates. This difference in attitudes suggests SDYs’ effects were at least partly cultural.

Why did first-hand exposure have a larger impact?

The outsized impact of the Sent-Down Youth may also be explained by prestige bias. These urban women were more educated, independent, and higher in status. Young rural girls may have seen them with excitement and awe!

In my own research in the Zambian Copperbelt, I assessed the comparative importance of gender sensitisation versus first-hand exposure to women in stereotypically masculine domains. Abstract messages may just be dismissed, “kukanda fye” (it’s just talk). Really seeing a woman providing for her family, driving a large truck to the copper mines, or thriving in business is much more impactful.

Population Movements

The large effects of population movement have also been demonstrated through prior work on Stalin’s forced deportations:

Toews and Vézina show that Soviet places which received educated intellectuals, exiled to prison labour camps, now have higher human capital and greater prosperity.

Miho et al show that places which received more Protestant deportees now have higher female labour force participation and lower fertility. This effect is strongest where deportees make up a larger share of the population.

CCP Radio vs. Prestige Bias

Qian and Chen’s studies on Communist China’s cultural interventions offer profound insights into the mechanics of social change. Their findings reveal a clear hierarchy of influence:

First-hand exposure to women with higher status (most powerful)

Consistent ideological messaging via mass media

The Sent-Down Youth movement, bringing educated urbanites to rural areas, proved more impactful. While ideological propaganda is powerful, it seems secondary to first-hand exposure and prestige bias.

Yet, the Communist context exposes two paradoxes.

The CCP championed female education and employment to maximise labour output. Having reached this goal, there is no further state support for equality. Female autonomy was never part of the Plan.

China also reveals a critical paradox. While the state could suppress Confucianism, via totalitarian social engineering, it also suffocated independent activism, inhibiting feminist resistance. The CCP maintains ideological dominance, while Baidu Tieba (a masculinised message board) teams with misogyny.

Culture is NOT persistent, it is continually contested.

Totalitarian regimes may create dramatic social experiments, but without the freedom to debate and shape societal norms collectively, progress remains fragile. Lasting cultural change requires not just exposure to new ideas or even people, but liberty.

Bravo to Ruoyu Qian, Yi Chen, Ziying Fan, Xiaomin Gu and Li-An Zhou for two phenomenal papers about the drivers of ideological change in Communist China.

I recommend a paper titled by The Quiet Revolution: Send-Down Movement and Female Empowerment in China