Can We Track the Great Gender Divergence on TV?

Is the secret to women’s liberation in your living room?

While each culture has a unique cultural inheritance, creating a spectrum of acceptability, conservatives and progressives are constantly battling to control state power and media platforms.

Cultural entertainment gets us hooked! Through exciting plot-twists and comic wit, viewers become engrossed in alternative realities. Imagination enables us to transcend our local communities and contemplate something different - whether that is moving to the city and forging a career or leaving abusive husbands and finding true love. Media can also resolve social coordination problems: whereas each individual may self-censor for fear of ostracism, television can make deviance appear prestigious, thereby encouraging wider emulation. The ‘Quiet Revolution’ unfolds on screen.

Did Brazilian telenovelas about transgressive women - rejecting past shackles, forging economic independence and ultimately embracing their true love - encourage wider emulation? Could this help explain Latin Americans’ surging support for female employment? Meanwhile, does strict censorship across the Middle East and North Africa reinforce public conservatism, tying men’s honour to female seclusion?

The Great Gender Divergence

Jobs data is pretty spicy. Brazilian women born in the 1930s rarely worked outside the home - just 20% held jobs. Fast-forward to those born in the 1980s, and that figure jumps to 65! By contrast, the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia remain deeply patriarchal - with low female employment and representation.

Economists often link rising female employment to economic development. Claudia Goldin theorised a U-shape relationship, with female employment falling during early industrialisation but rises with the growth of white collar jobs. Iversen and Rosenbluth’s cross-country research confirms that service sector expansion boosts female employment. In China too, structural transformation narrowed gender pay gaps.

Yet economics cannot explain why MENA lags behind Latin America despite comparable wealth. The missing piece may be culture and media persuasion!

Culture is a Fist-Fight!

In 1900, the world was largely patriarchal, but some societies strongly idealised female seclusion, making women’s labor supply less responsive to economic opportunities.

Culture, however, is contested! In Central Asia, the Soviets crushed religion and mandated jobs for all. The Chinese Communist Party mobilised radio and Sent Down Youths to engineer cultural revolution. Over in the US, McCarthyists persecuted Hollywood progressives, which actually raised votes for Republicans. Chilean dictator Pinochet rewarded religious supporters by imposing media gags. In India, the televised epic ‘Ramayan’ shifted religious identity and voting patterns.

Across Muslim states, the 1970s heralded religious revivalism. While the Quran was already valorised as the literal word of God, religious authorities leveraged new communication technologies, mass education and Saudi funding to promote strict adherence. Politicians in Egypt, Pakistan, Malaysia and Nigeria sought to gain legitimacy by appeasing religious sentiments and enforcing censorship. Egypt’s 1976 law proscribed cinematic portrayals of heresy, magic, immorality, sexuality, and alcohol, while mandating respect for ‘the sanctity of marriage, family values and one’s parents’. Progressive Persian dramas - like “About Elly”, “Offside”, “Circumstance”, and “Women without Men” - continue to be restricted and banned.

Scriptural literalism slams the door shut. When sacred texts privilege a cultural straitjacket, dissent becomes heretical. Take the male breadwinner ideal. While economists may write papers on how reliance on a single income increases vulnerability and inhibits upward mobility, God says this is the pathway to eternal paradise. (No offence to #econtwitter, but you can’t trump salvation). Here’s where autocrats and I are fully aligned: they too recognise the disruptive power of cinema!

Over-riding religious resistance, powerful states can champion alternative models of prestige. In the Islamic heartland, MBS marshals state media to promote cultural liberalisation. Saudi teenagers Aljohara and Ghada enjoyed “Barbie: The Movie”, finding the lack of censorship surprising! Over in UAE, the government donated land to build a Hindu temple, celebrating inclusivity.

Latin America has seen similar struggles. From 1850, reformist leaders challenged Church power with secularising reforms, and European migration brought new ideologies of socialism and anarchism. But in ‘64, organising ground to a halt. Only with democratisation and greater freedoms can feminists protest for legislative reforms. Outcomes aren’t pre-determined, but up for grabs! Media platforms function as cultural marketplaces, where competing coalitions vie to define prestige.

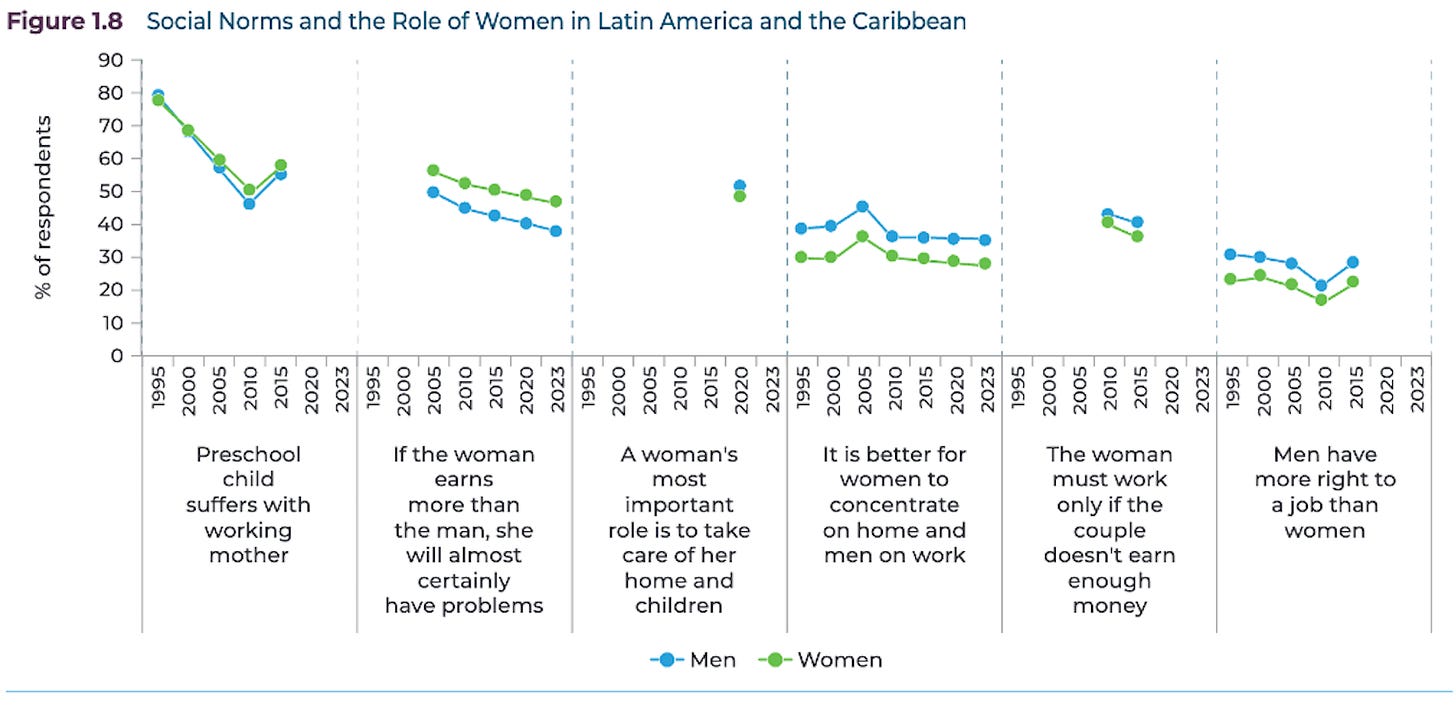

Between 2008 and 2015, Latin Americans became more supportive of female employment, a shift strongly correlated with higher labour force participation. So, what’s catalysed this change?

What about Secularisation?

Most Latin Americans remain religious, as visualised below. While statistics show national averages, let me add excepts from my own qualitative research in Costa Rica - where professional couples invited me to their church, and a female doctor’s home featured multiple life-sized posters of Jesus.

Telenovelas

In Brazil, Costa Rica and Mexico, I’ve conducted life history interviews to identify the the drivers of cultural change. Older participants tended to normalise male intimidation, hierarchy, infidelity and abuse. Their granddaughters expect much better! When reflecting on likely catalysts, many pointed to telenovelas.

Far from reflecting Brazil’s social realities, telenovela storylines spun aspirational visions of progress, strategically backed by the 1964-85 dictatorship. Military leadership invested in television for nation-building, consumer growth, and political control. Partnering with TV Globo, which commanded up to 100% of prime-time viewership, they subsidised TV sets and built satellite distribution systems. Television ownership in Brazil surged from just 8% to 81% of households between 1970 and 1990. It was essentially Import Substitution Industrialisation for culture!!

Telenovelas became the dominant form of entertainment, with families (or entire communities) nestling together, emotionally invested in melodramatic rollercoasters about romance and rivalry!

“It was something the entire nation did for an hour each evening and then talked about incessantly the following day… Telenovelas are the routine of public life, uniting citizens … a pervasive part of everyday conversations” (Erlick 2017: 144)

Visions of Progress!

Telenovelas were crafted as narratives of development: protagonists left rural backwaters for urban modernity. In Selva de Pedra (1972), Cristiano Vilhena rises from a poor background to a successful businessman in Rio. In O Rei do Gado (1996), Bruno Mezenga becomes a powerful cattle rancher. Beyond upward mobility, telenovelas also celebrated personal freedom and embracing true love.

Studying screenplays, I suggest that these aspirations shaped gender narratives. Heroines from humble origins faced infidelity, betrayal or hardship. Refusing to suffer in silence, they gained financial independence and pursued the man they loved. While many feminists often dislike this end-goal, it’s actually rather popular. The truth is that many women like romance and want a man who makes her feel GREAT!

In this way, women became stars: shows centred on their subjectivity and happiness, while they gained a place in the public sphere. Erlick comments,

“When telenovelas… stress women’s power in decision-making, it is through her success in work and her wiles in getting her Prince Charming… María Inés [in Mexico] goes from being the passive housewife to the woman who takes control of her own life and desires… Her lover.. defends his own emotions and validates hers.. Telenovelas are the voiced dreams of the outsiders becoming insiders… Women became the protagonist..

“There was a depoliticised expansion of the female universe and the perverse valorization of the “strong woman”, who, in addition to being responsible for the family, must work and can aim for romantic satisfaction” (Erlick, 2017: 67-68; 70; 142).

Writers and directors (usually educated at secular universities) took great pride in these creative productions, even probing social tensions, pushing difficult issues into the limelight, initiating debate, stretching the boundaries of permissibility (Erlick 2017:69; Svartman 2021: 17). By avoiding feminist labels, progressive narratives may have garnered wider public support.

I suggest that creatives tried to excite and engage, shedding light on social tensions and celebrating personal triumph. Here, they must walk a tightrope of stretching the boundaries of permissibility, without aggravating state censors or religious conservatives. Pinochet’s Chile was the exception that proves the rule - appeasing conservatives by imposing media restrictions. As long as writers stayed within Latin America’s spectrum of acceptability, it was fine to push.

Icons:

Tieta (1989-1990) was a hugely popular story of female defiance. The protagonist returns to her hometown in Bahia, 26 years after being beaten and expelled by her father for alleged promiscuity. Now wealthy and successful, Tieta not only exposes local hypocrisy but also fights industrial polluters!

“Senhora do Destino” (2004-2005) was seriously successful and celebrated female determination. It begins with Maria do Carmo moving to Rio de Janeiro with her five children in search of better opportunities. The story then jumps several decades, showing Maria as owning a building supply store. Female characters become seriously prominent - Daiane wins the Nobel Peace Prize while Bianca is elected mayor.

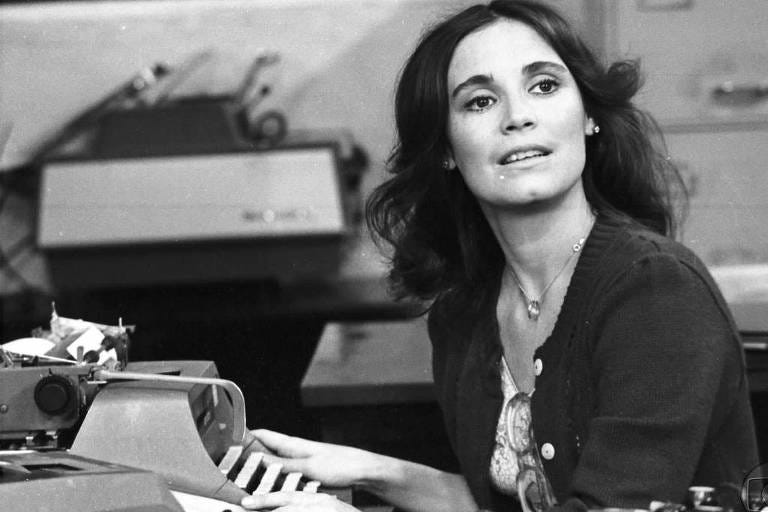

The list continues… “Malu Mulher” (1979-80) portrays a newly divorced woman, who independently raises her teenage daughter, re-builds her career and carves her own way. “Em Delegacia de Mulheres” (1990) centred on a women’s police station, where female police officers and detectives investigate crimes against women - such as domestic violence and sexual assault. And in ‘Anos Rebeldes’ (1992), Heloísa challenged the Brazilian dictatorship.

Daniel Filho is best known for producing the Oscar-nominated City of God (2002), but also produced and directed numerous dramas centred on women. Teenage Confessions (1994–1996) followed four sisters navigating identity and sexuality; Justiceira (1997) starred a female ex-cop fighting crime; while Mulher (1998–1999) showed women doctors tackling domestic violence and cancer.

Evidence: Life Imitates Art!

Two brilliant studies demonstrate telenovelas’ tangible impact on fertility and divorce.

Eliana La Ferrara, Alberto Chong, and Suzanne Duryea’s (2012) found that women living in municipalities that received the Globo signal subsequently had fewer children. This effect was strongest among less educated and less wealthy women in their mid-to-late childbearing years. Fertility declines were especially strong when scripts also featured social mobility - that is when fewer births were associated with prestige.

Content analysis revealed a likely mechanism: 72% of main female characters under 50 had no children whatsoever, which significantly diverged from Brazilian reality.

The most compelling evidence of cultural influence is that in areas receiving the Globo signal, 33% of new parents named their children after novela characters, compared to just 8.5% elsewhere!!

In a separate paper, Chong and La Ferrara (2009) demonstrate that Globo availability significantly increased separations and divorces.

This is plausibly due to telenovela content - rife with infidelity! Coding all the 7pm and 8pm novelas from 1965 to 2004, they find that 28% of novela’s main female characters were married and 25% were unfaithful. Between 1975 and 1984, 20% of main characters were divorced or separated, and this significantly diverged from Brazilian reality. Divorce was only legalised in 1977. Moreover, census data from 1970 to 1991 suggests that only 2.8% of women were actually divorced or separated. But when municipalities got the signal, separations went up!

Can We Track the Great Gender Divergence on TV?

Building on these brilliant papers, someone clever could explore whether cross-national differences in television content contributes to divergent rates of female employment. Now, if you’re reading in May 2025, this plan may sound impossible, but… technology is rapidly evolving and it may soon be perfectly manageable!

Build a Comprehensive Corpus.

Compile a dataset of scripts or detailed synopses for the 100 most-watched shows per country (1970–2020), prioritising major networks (e.g., Globo’s Memória Globo, BBC archives).

Scrape subtitles from streaming platforms (Netflix, YouTube) or access network archives.

Content Analysis with Natural Language Processing

Use transformer-based natural language processing models, fine-tuned to classify female characters’ narrative arc (e.g., transitions from housewife to running a company).

Develop sentiment analysis to quantify portrayals of female careerism, assessing whether professional success is depicted as aspirational (e.g. does she wear nicer clothes, receive admiration, and achieve romantic bliss?)

Computer Vision

Leverage vision-language models (like CLIP, DALL-E3, GPT-4V or successors) to track visual cues of prestige (such as power suits). Complementing textual analysis, this would track female protagonist’s social status changes over the course of the story.

Cross-Cultural Comparison

Construct a ‘Progressive Index’, scoring shows based on representation and positive sentiment towards careerism.

Track Progressive scores across regions and decades.

Regress these scores against lagged rates of female labor force participation. Don’t add controls.

Wouldn’t this be awesome? It might shed light on whether media portrayals influenced female employment across world regions. Below is my hypothetical estimate of final output. Let me know what you find! Happy viewing!

Related Essays

What do Hollywood and Bollywood regard as Shameful? (US and India)

Reel Politics: How the Hollywood Blacklist Changed American Minds (US)

The Power of TV (US)

How do Radical Ideas Go Mainstream? (US Women’s Magazines)

How do Dictators Stay in Power? "Censorship as Reward!" (Chile)

Netflix and Change: Tracking Cultural Flux in Autocracies (Saudi Arabia)

Structural Transformation Enables Women to Rewrite the Script! (East Asia)

Who Killed the Patriarchy? CCP Radio vs Prestige Bias (China)

Did the Communications Revolution amplify Feminism? (Global)

Post-script: the best film I’ve seen in the past year is “The Seed of the Sacred Fig”, on patriarchy under the Islamic Republic. Tremendous!

Very neat brainstorm of “Does life imitate art?”

Since decisions about what sort of content to air or allow on TV are made by elites, is this actually a theory of how elite mindsets influence broader opinion and culture?

In India, the Ramayana aired on state-run TV. There were choices made to produce and air it. I've heard the then-prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi, encouraged it. Similarly in Pakistan, the push towards a greater role of religion in society (and mandatory headscarves for women on TV) was Zia ul Haq's doing.

Even if TV isn't state-run, the decision-makers are high level executives at TV networks. They are the ones who choose whether to air culturally liberal or transgressive or conservative content. Of course, they do it with the goal of profit maximization, but artistic products have enormous room for curation and discretion.

State authorities can then decide whether to allow/encourage this content or restrict it. Artists receive explicit or implicit state subsidies/tax breaks in many countries.

To continue with your metaphor of culture as a fistfight, are there any instances of powerful elites losing the fistfight? I'm referring now to cultural conflicts between elites and the broader population, rather than between elites. Or does backlash only win out when there are other powerful elites behind it?