How do Radical Ideas Go Mainstream?

Secrets from 1970s Women's Magazines!!

Over the 1970s, Americans rapidly became much more supportive of gender equality. Departing from the cult of domesticity, families increasingly came to support equal rights at work and in politics, as well as the transformation of intimate relationships.

What enabled this remarkable shift?

Most Americans encountered feminism indirectly, yet media coverage was overwhelmingly hostile. Mainstream news, like the New York Times, focused on outrageous protests and vilified feminists as rebellious extremists.

Some scholars point to ‘counter-publics’ - ‘feminist consciousness-raising’ in small groups, which problematised sexism and envisioned more egalitarian alternatives. Feminist newsletters and bookstores also gained popularity - at least in San Francisco. But how did radicalism spread beyond small activist circles to influence millions of Americans?

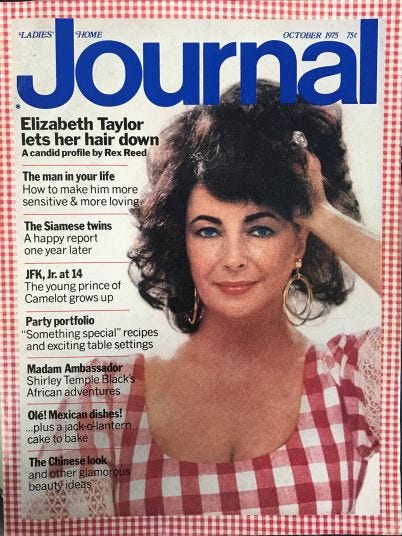

A tremendous new paper by Francesca Polletta, Debra Boka, Caroline Martínez and Mutsumi Ogaki offers an answer which I had previously overlooked, but immediately found compelling. Women’s magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and McCall’s made feminism relatable. And they reached a massive audience - 50 million plus. A single issue of McCall’s reached one in four American women! Bam.

I LOVE LOVE LOVE THIS PAPER!

It perfectly aligns with my theory that culture is a struggle for ideological persuasion through mass media, whereby ideas tend to be adopted if they can be marketed as consistent with existing values and supported by like-minded peers. This paper is seriously important for everyone interested in social change.

So let’s talk about “WOMEN’S LIBERATION AND YOU!”

Methods

Polletta and colleagues employed both qualitative and quantitative strategies to examine how 1970s US women’s magazines covered feminism:

How did editors of women’s magazine conceive of their audience? Here, they draw on industry reports, trade publications, editor memoirs, oral histories, and interviews with former writers and editors.

Comparative content analysis of five leading women’s magazines, alongside the New York Times in 1970-71. Using digital archives, they identified articles containing terms like ‘feminism’, ‘women’s liberation’, ‘ERA’, and key feminist figures:

Tracking discussions of both formal workplace and political equality, as well as gender roles in public life;

Attending to expressions of support from ordinary women.

How did articles position their readers in relation to feminist ideas of equality in the workplace and at home?

The New York Times Dismissed Feminism as Irrelevant

As little as 50 years ago, feminism was bitterly opposed by mainstream media. The New York Times depicted feminists as wild radicals, out of touch with ordinary American women, who were either uninterested or vehemently hostile. Coverage centred on legislative battles, intellectual trends, and feminists’ disruptive protests. One Times article detailed how shoppers were disrupted,

Feminists were sometimes derided as killjoys, fixated by oppression, unable to understand humour, art and emotions. Classic put-downs included “Wait till Women’s Liberation hears about …”. Readers were encouraged to roll their eyes in despair.

When the Times quoted opinion leaders, like politicians and celebrities, they tended to deride and diminish. The Attorney General was asked if the US would invade Jordan, “Mr. Mitchell grinned and said, ‘No, we’re invading women’s lib’”.

The paper portrayed successful women as having no interest in or need for feminism. When the Times covered women breaking into male-dominated domains, it cast them as succeeding without feminism, and unsupportive. Of the female football commentator, the Times noted, "women's lib doesn't interest her"; the female commercial pilot did not "consider herself a feminist", and philharmonic musicians "had not experienced one instance of discrimination against us".

So what about women’s magazines?

Women's Magazines: From Opposition to Advocacy

Initial Resistance

Initially, magazines portrayed feminists as angry, “extreme”, “militant”, and “wildly bizarre”. Betty Friedan famously tarred them as the enemy - glorifying domesticity.

In 1970, the activist group Women in Media occupied the editor’s office of the Ladies’ Home Journal, insisted on a female editor, more Black women staff, daycare for employees, and more feminist stories. Compromising, they settled for an eight page insert on consciousness-raising, contact information on feminist organisations, and rephrasing “Can this Marriage be Saved?” to “Should this Marriage be Saved?”.

So what happened next? Polletta and colleagues do not claim this protest had any causal effects, but over time women’s magazines showed curiosity and support.

Making Feminism Appealing to the Masses!

Women’s magazines created a space for writers and readers to share their intimate journeys of feminist self-discovery. How should we raise our daughters? Could women be feminine and have careers? To what extent should marriage be about dependency?

Perusing vintage magazines on eBay, I found more examples:

Articles typically began with scepticism, explored with curiosity, found common ground, and ultimately expressed support. In Good Housekeeping’s first major piece about feminism, the author describes herself as happily married with children, but is nonetheless “grateful to the karate-choppers”. She wanted men to share housework, abortion on demand, and for girls to believe they are equally good at maths.

“the struggle for women’s rights begins at home. It begins in our private lives, with our fathers, husbands, and sons. It begins with our own decision no longer to accept outmoded roles that men have been assigning us for centuries”.

Swapping Radicalism for Relatability

Amazingly, Polletta and colleagues investigate how articles were redrafted!

Take writer Sophie Burnham. Her early drafts expressed feminist rage, radicalism and revolutionism, but this was all edited out. The magazine’s final published version described feminists happily married, searching for self-discovery, while being ‘gentle, articulate and polite’. Feminist consciousness-raising was not portrayed as subversive, but instead likened to “two women sit[ting] at the kitchen table, drinking coffee and discussing their husbands and children”.

While purists may resent censorship, I strongly suspect that these editors made the feminist movement much more relatable to the masses.

Writing for the Median Woman

When writer Pogrebin profiled consciousness-raising, she wrote for the woman under the dryer at the salon. Rather than focus on hippies smoking pot, or privileged elites at Berkeley or Barnard, she made feminists appear like the woman next door. She described them as “people I know from PTA”, referre]k, student experiences at Iowa State University, and featured quotes from women from Detroit and Dallas.

By profiling married couples sharing household responsibilities, women’s magazines normalised ‘undoing gender’. They showed ordinary families embracing equality in the home. Personal stories included a man caring for his son while his wife worked, Polletta and colleagues suggest that these relatable, personal journeys echoed television dramas with sympathetic fictional characters.

Indeed! Let me add, US TV shows normalised gay characters in this same way. Sitting comfortably in their living rooms, watching their favourite shows, viewers watched nice, relatable protagonists embrace gay friends. In the US TV show “Soap”, characters reflected, learnt and embraced more liberal values. In “All in the Family”, Archie Bunker, a working-class patriarch, initially reacted with disbelief when his friend Steve came out as gay. Over time, Archie became supportive.

This gels with a key point made in Michael Morris’s book, “Tribal”. Humans are much more likely to accept new ideas if they perceive them as supported by their peers and heroes, as well as if they are seen to resonate with core values.

Note below: “Women’s Lib and Me: Our Readers speak Out”.

A Community of Readers!

What might explain this slant? Why did magazines emphasise the similarities between feminists, themselves, and readers? Polletta and colleagues suggest that magazines are intentionally orientated around a community of readers, also featuring readers’ letters and survey responses. Together, they celebrated a common project of self-discovery. One reader shared:

“that there are thousands like myself. While I have no desire to abandon my husband and children or unfurl my bra in public protest, I do have an intense need to survive as an individual”

Practical Advice

Women’s magazines provided practical advice - how to talk to your husband about sharing housework, whether to keep your maiden name, how to raise daughters with greater aspirations. Carol Tarvis, former magazine writer, shared that there was a sense of “exhilaration”

“The exhilaration was: we have a whole lot of new stories to tell that we have been telling. The world is changing. Women are changing. There’s information women need to have and we’re going to get it in, along with the recipes and the home decorating tips”.

Here’s an example I found online:

“The man in your life. How to make him more sensitive and more loving”.

Ladies Home Journal masked radicalism with romance!

Collective Endeavour

Beyond individual journeys of self-discovery, women’s magazines also championed collective wins for women as a group - launching childcare centres, women’s studies programmes, and maternity benefits. Feminism was sold as a shared endeavour.

Progressive Editorial Choices

Perhaps we should give women’s magazine editors more feminist kudos. When Polletta and colleagues tracked readers’ letters, they also checked those which unpublished. Surprisingly, editors selectively cherry-picked letters that were more progressive, open-minded and modern! Surveys were also manipulated. Even when the majority of respondents said they were opposed to role-change goals, published articles tend to emphasise support!

Quantitative Analysis

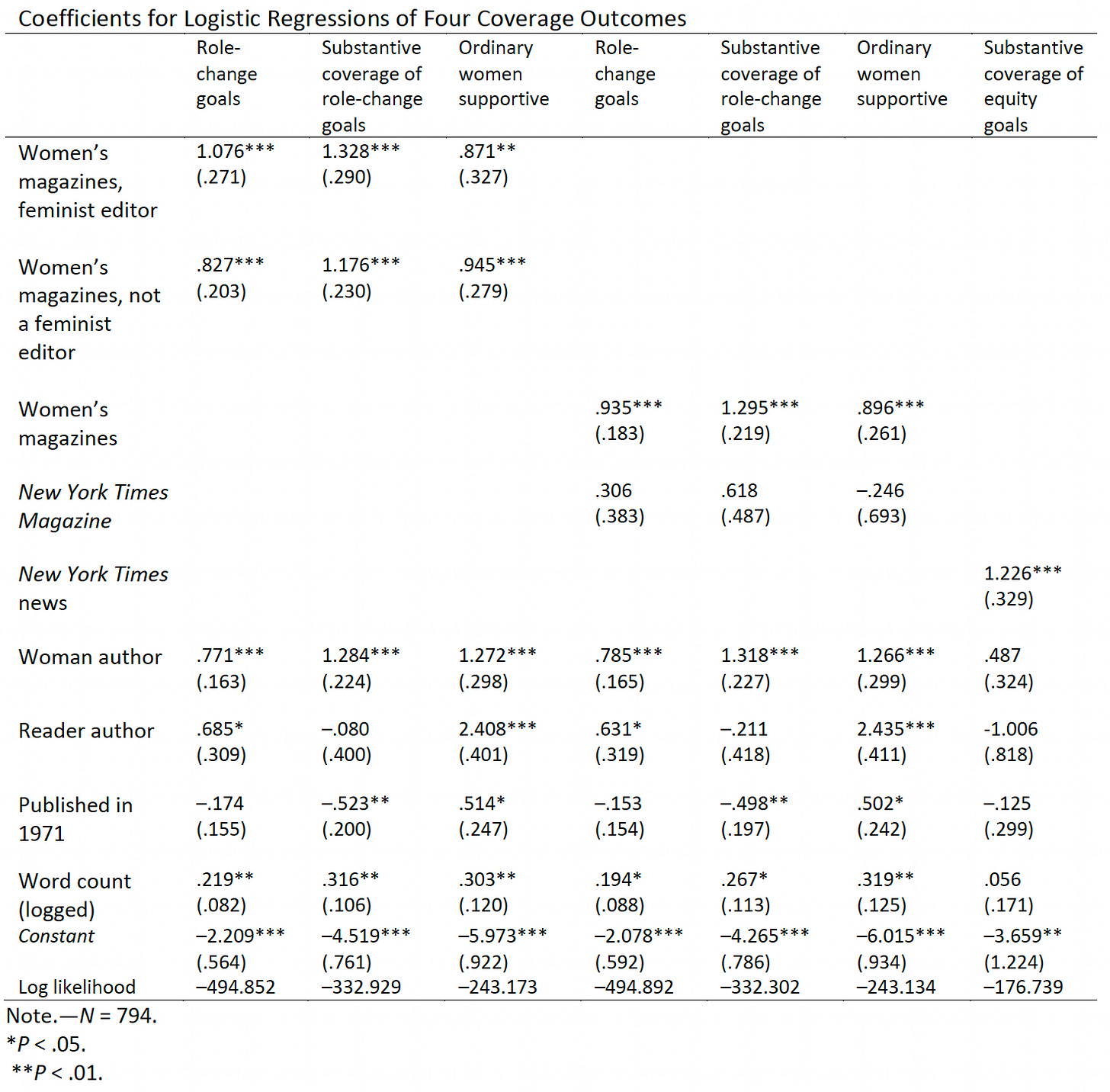

Magazines were:

2.6 times more likely than the Times to refer to the feminist movement as demanding changes in domestic gender roles

3.4 times more likely to cover role-change goals substantively

2.5 times more likely to quote ordinary women supporting the movement

Having a woman author increased likelihood of covering role-change goals by 77%

Even though most writers of the NYT’s women’s page were women, they were no more likely to cover the movement’s role-change goals or to cover them substantively.

Interestingly, these patterns held regardless of whether magazines had feminist editors. Polletta and colleagues suggest that commercial imperatives may have encouraged pro-feminist content, as magazines sought to convince advertisers that their readers were open-minded, sophisticated, and with major purchasing power.

How do Radical Ideas Become Normal?

BRAVO to Francesca Polletta, Debra Boka, Caroline Martínez and Mutsumi Ogaki. They persuasively highlight the importance of mainstream magazines in making radical new ideas more relatable and appealing. Also check out Polletta’s and Amenta’s latest book with “Changing Minds: Social Movements’ Cultural Impacts”.

Going beyond the article, let me suggest two broader lessons.

Each society has a unique cultural inheritance, a spectrum of permissibility, with conservatives and progressives constantly tussling for ideological persuasion and institutional dominance.

Over the 1970s, the US and Western Europe became radically more gender equal, because cultural entrepreneurs marshalled the latest communication technology to persuade the masses. Strategically, women’s magazines appealed to the woman under the dryer, chimed with existing values, while showcasing support from peers.

Not all activism is effective, just as not all cancer treatments work! As we see from women’s magazines, it’s critical to keep a finger on the popular pulse and strike a chord. Push too far and the elastic band will snap, triggering backlash.

But strategic framing is not the whole story. Western feminists were also surfing on unique structural trends, which were expanding the spectrum of permissibility. Democratisation and secularisation enabled anti-establishment critics to speak out, while skill-biased technological change generated demand for women in respectable professions. Back in the 1970s, communications technology had high barriers to entry, creating a degree of homogeneity. As entire communities consumed similar magazines and television shows, they tended to stay on the same page. This encouraged more broad-based cultural change.

Personal note: browsing on Ebay, hunting down women’s magazines, I confess I felt a little sad. My grandmother (born in 1926, and graduated in Economics) always bought women’s magazines. She was the kindest, warmest person in the world. If only I had asked what she read and thought during the counter-cultural revolution!

Talking of 1970s media, I LOVED “Good Girls Revolt”. Check it out!

Related Essays

P.s. thank you to Christopher Pepper for alerting me to teenage girl’s magazine, “Sassy”. Contrary to Freud’s assertions of penis envy, the writer says, no, we envy that men are given so much praise and respect!

I confess reading this article made me more cynical about the impact of feminism on society. It sounds like there wasn't necessarily any period where society had a rational, wise debate about whether gender roles are useful or not. Instead, the change was driven by

* fashion ("our own decision no longer to accept *outmoded* roles", emphasis mine)

* deception and lies ("editors selectively cherry-picked letters that were more progressive, open-minded and modern! Surveys were also manipulated. Even when the majority of respondents said they were opposed to role-change goals, published articles tend to emphasise support!")

* crass commercialism ("Polletta and colleagues suggest that commercial imperatives may have encouraged pro-feminist content, as magazines sought to convince advertisers that their readers were open-minded, sophisticated, and with major purchasing power.")

Is it any surprise that women's happiness has decreased in the decades following "women's liberation"? Seems like this change was more of an accident of history than some sort of enlightened wisdom.

Has it actually gone well? Why is it that so few are willing to defend it directly on its own merits, as opposed to accusing critics of being "outmoded" and similar (there's that fashion dynamic again)?

I'm definitely open to the possibility that it's been positive, but that doesn't seem obvious...

Fantastic article - is it just me, or do most of the contrary comments seem to come from men? Just sayin'.

I found this a particularly salient observation:

". . .entire communities consumed similar magazines and television shows, they tended to stay on the same page. This encouraged more broad-based cultural change."

Our country has changed since this was true, and not for the better imo.