Televising Male Disapproval

Let me present an argument. Do you agree?

Sexual harassment can persist in a positive feedback loop. Where men harass with impunity, this sustains fears and paternalistic restrictions;

If criminal justice systems are over-burdened or systematically sexist, they fail to provide decent protection or deterrence;

Close-knit communities do, however, have strong systems of social policing.

Social policing can be hugely effective - in achieving their desired outcomes (whatever these may be). In places where reputations secure inclusion in vital networks, people care about “what will people say”.

Men moderate their public behaviour to secure wider approval. Middle-class men in Delhi, for example, are acutely conscious of how they are judged and perceived, so constantly try to appear cool and smart.

Expectations of peer condemnation are thus key causal mechanisms - even if inaccurate. When expectations change, so does behaviour (as shown in Saudia Arabia, Uganda, and rural Zambia).

Do you agree?

If so, then let me propose a research idea:

If we want to tackle sexual harassment, we should build on what actually works. In places where state policing is weak and social policing is extremely effective, it may make sense to leverage those systems that work.

Now, suppose there was a massive media campaign that amplified expectations of peer disapproval. Popular television shows might portray ordinary men chiding their peers for sexual harassment. Could a popular, long-running television series generate expectations male disapproval?

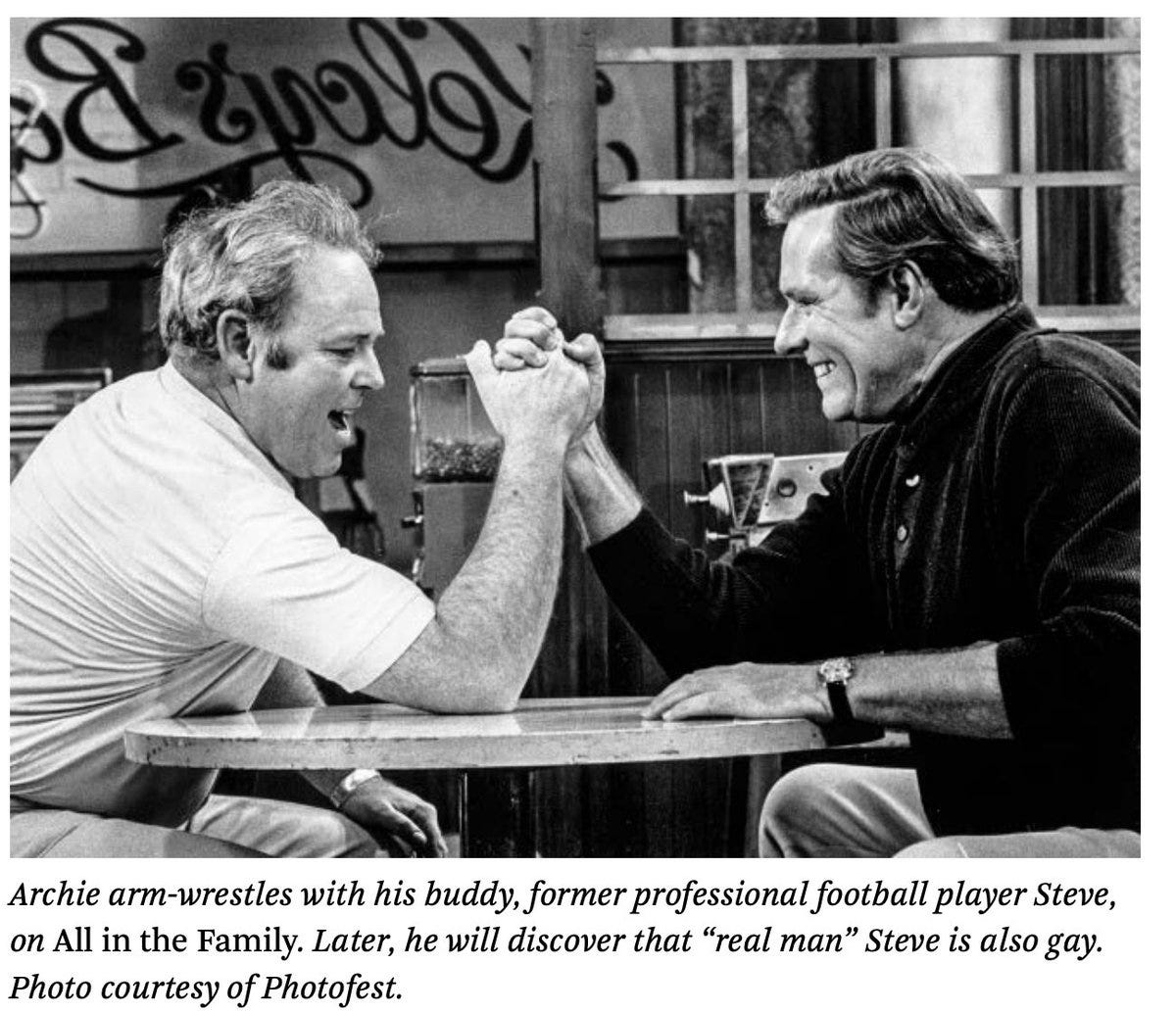

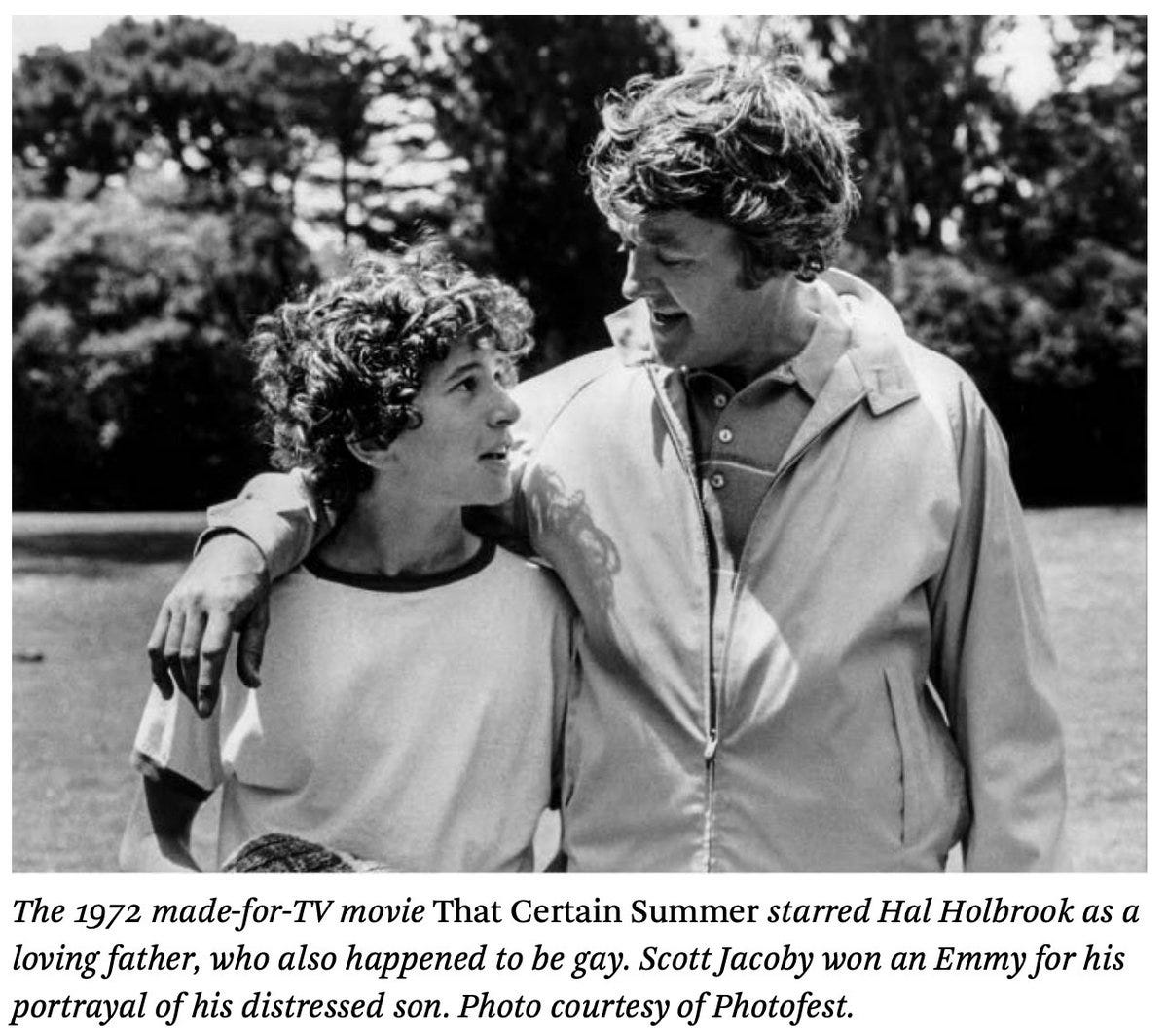

Sitcoms can take viewers on a journey of reflection, as empathetic and well-loved characters iteratively reflect and reform their behaviour. In the US TV show “Soap”, characters reflected, learnt and embraced more liberal values. In “All in the Family”, Steve came out to Archie (a working class patriarch), but Archie initially thought it was a joke. Over time, Archie comes to question his priors. Other television shows similarly depicted nice, relatable, family-orientated people being friends with gay men.

Films and television shows also appear to have a stronger influence on people’s expectations of their community if characters are relatable, on modest incomes.

TV shows may have a stronger causal impact on sexual harassment if characters are neither rampant sexists (who totally ignore harassment) nor woke progressives (who seem unrelatable). Just like the Aristotelian mean or Goldilock’s ideal porridge, we’d want something in the middle.

Shorter adverts would doubtless be cheaper, but it takes telenovela-style duration for audiences to increasingly identify, empathise and become invested.

Charismatic, empathetic, and inspirational characters could start with a middling degree of sexism (so as to appear relatable), and then increasingly call out their peers, expressing disapproval, perhaps even showing ostracism.

(Note, this is totally distinct from films in which a heroic brother battles the criminal underworld to avenge his sister’s rape).

TV sitcoms, showcasing male disapproval, seem like promising way of shifting expectations and tackling sexual harassment.

When I lived in Mexico I walked every morning with a group of professional women in a socially conservative area. They regularly discussed the previous night's soap opera in which gays were taken as a given. I concluded it gave them a safe way to explore the issue without referring to family, neighbors, or friends. Not your case but indicative of the power of this kind of television.