Why is Fertility Collapsing, Globally?

Something dramatic is happening everywhere all at once: fertility is plummeting, with major implications for economic growth and social stability. Yet public discourse is seriously weird, crudely:

Speculations, which are sometimes ideological/ with tenuous evidence

Silence from many progressives, due to (1).

Personally, I would like to avoid both (1) and (2).

So, to contribute to public conversations, let me outline the descriptive data on collapsing fertility, why this matters for economic growth, share ideas for future research, and propose a test for any new theory.

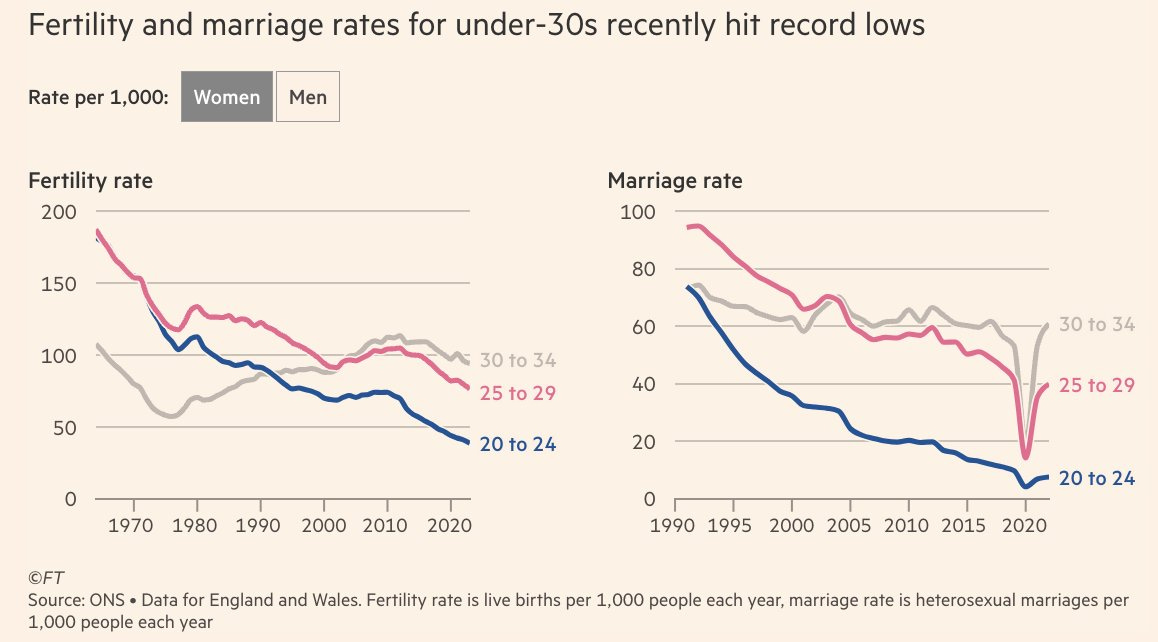

Fertility is Nose-Diving

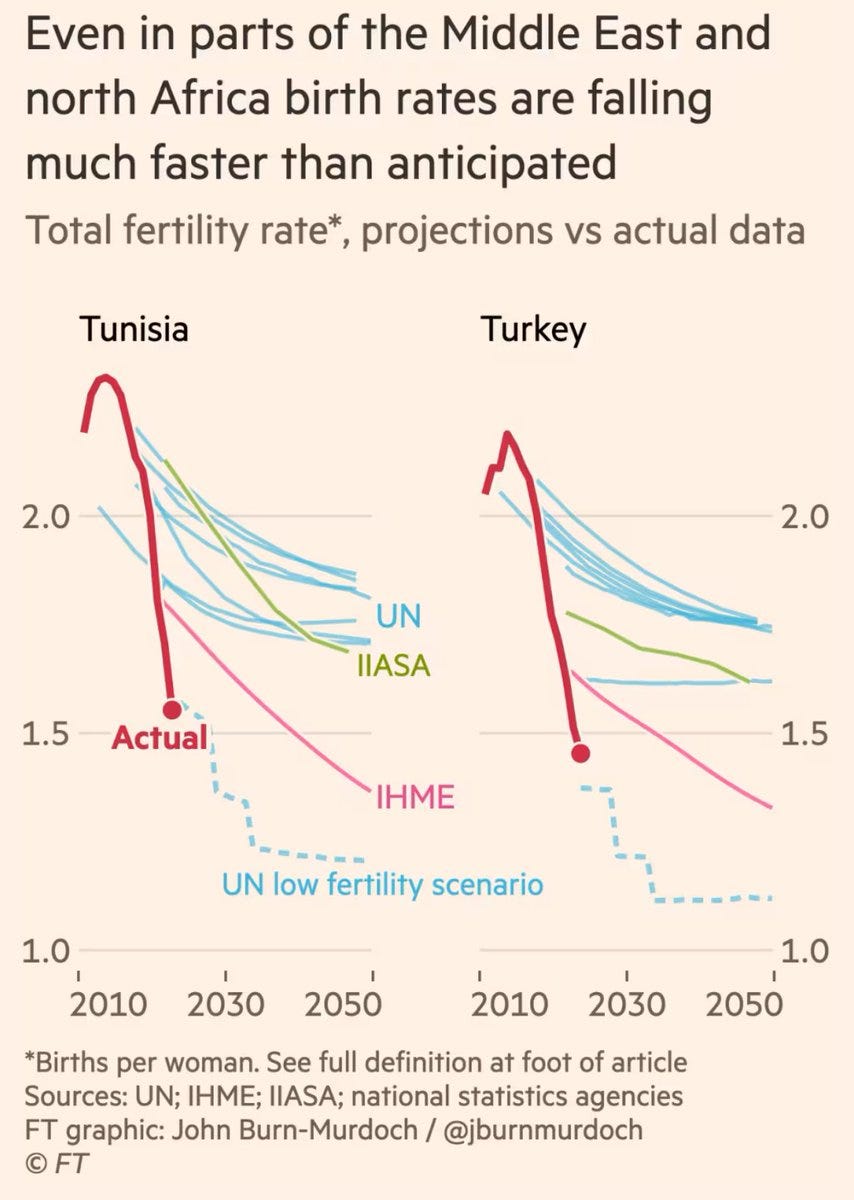

Fertility is nose-diving faster than anyone expected. In 2000, US total fertility rate was over 2 children per woman. But now it’s 1.6. In China and Costa Rica, it’s 1.1, in Puerto Rico and Chile it’s 0.9, in Turkey it’s 1.5, in India it’s 2.1 - barely at replacement. Even among foreign-born Mexican immigrants to the US, fertility has crashed.

How Does Fertility Affect Growth?

Aging populations create multiple challenges for economic dynamism.

Shrinking Workforce

Older people have far lower rates of employment. Fewer young people also means fewer startups. As shown by Hopenhayn and colleagues (2022), this shifts the entire economy toward older, larger, but less dynamic firms. Firm aging may help explain increased market concentration, declining business dynamism, and changes in labor's share of income - all key factors in economic vitality. Already in the United States, population aging has begun to suppress economic growth.

Fiscal Squeeze

Across the European Union, tax revenue is increasingly spent on elderly healthcare and pensions. Between 2003 and 2019, Spain’s pension expenditure-to-GDP ratio rose sharply - by 3.8 p.p. This makes it even harder to invest in green industrial policy and climate mitigation after terrible floods.

One alternative is to ramp up taxes on young people.

Low and Middle-Income Country Struggles

Where female employment is low, like in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, one man may be supporting FOUR elderly parents. This fiscal pressure threatens sovereign debt ratings, making it more expensive for these countries to borrow.

Domestic consumption gets hit

As people save more for retirement (as in China), they spend less on local goods and services. This creates a downward spiral - lower demand means less economic activity.

Social tensions

If there is an abundance of young men (due to skewed sex ratios) and the population is ageing, then there will be a shortage of young brides. As South Korea’s young men face an adverse dating market, frustrated singles become collectively hostile. India may soon see similar patterns, with rising male resentment.

What’s the Cause of Japan’s Malaise?

Japan’s experience offers a wake-up call. Between 1991 and 2019, Japan’s economy grew by just 0.83% annually, while the US achieved 2.53%. Many economists blamed Japanese monetary policy.

But when macroeconomists Fernández-Villaverde, Ventura, and Yao dug deeper, they revealed a crucial plot-twist. Innovatively, they examined GDP growth per working-age adult. By this metric, Japan's performance (1.39% annually) comes much closer to that of the United States (1.65%). The key difference wasn't policy - it was demographics. Japan's working-age population is shrinking.

Immigration to the rescue?

For rich countries to maintain their working-age population ratios in 2050 through permanent migration (where each worker brings one dependent), Lant Pritchett estimates they would need to become 40-50% foreign-born. I visualise this below:

Diversity can power innovation. Max Posch and colleagues find that in the US, from 1850 to 1940, interactions between individuals with different skills, expertise and perspectives were a key driver of technological breakthroughs.

However, productive collaborations are not inevitable. Just look at ethnic violence in South-East Asia or Hindu Nationalism in India. Nation-building is really valuable, learning from multi-ethnic, democratic Indonesia. Right from the early 1900s, the Indonesian National Awakening championed national unity. ‘Pancasila’ nationalism was then ritualised in schools, civil service training, ideological propaganda, and even resettlement. This has helped forge social cohesion, trust, and camaraderie and commitment to democracy.

One more word of caution: the world is a closed and shrinking box. As all populations age, competition for talent will only intensify. Countries with sluggish productivity and/ or unaffordable housing may struggle to attract the brightest minds. Geniuses in India may well shun Europe and head West. That’s certainly true for graduates of the renowned Indian Institutes of Technology. Europe’s real problem is that we are not a competitive destination.

What’s Happening Everywhere All at Once?

The usual suspects - economic development, cultural liberalisation and feminism - are ultimately inadequate. Here’s my strict analytical test for any theory:

It must explain both the global collapse and local variation.

Country-specific studies, while valuable, often miss the bigger picture. The Economist recently blamed England's falling fertility on housing prices and delayed motherhood. But how does that explain similar nose-dives in rural Guatemala?

Unsubstantiated, sweeping assertions prove equally inadequate. Nicolas Eberstadt speculates that it’s all about rising autonomy. But that can’t explain why fertility has also plummeted in Saudi Arabia, Egypt and India, where women are often heavily restricted. Moreover, it overlooks a crucial puzzle: why do some autonomous women actively choose to have kids? In the US, graduates have more children. What drives this positive choice?

‘The motherhood penalty’ also gets blamed. This may be an important economic consideration in certain societies, but it won’t explain the decline in Turkey and Tunisia where female employment is quite low (respectively 35% and 26%).

Should governments just offer larger pronatal incentives?

South Korea’s President has declared a ‘national emergency’ and offered more support for parents. Beijing too has just announced raft of policies to encourage babies. Across the OECD, governments are upping their spending. But a wealth of research suggests these fail to mitigate the downward trend.

What Might Explain the Global Collapse and Regional Variation?

Let me highlight three key factors, which may hold to differing degrees:

Rise of singles

Personal entertainment

Costs: educational arms race and childcare

The Rise of Singles

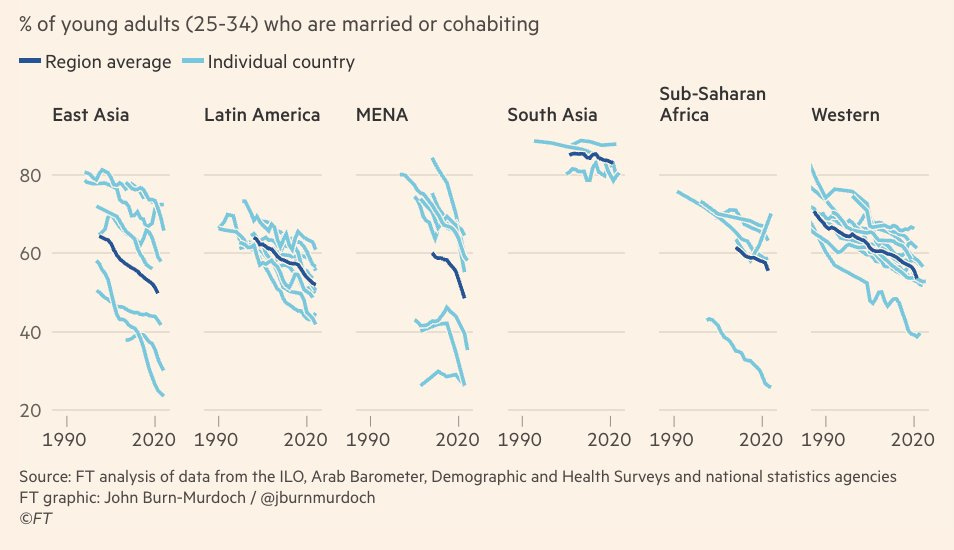

Coupling and fertility are falling. In Finland, Mexico, Peru, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey and the US, both metrics point downwards.

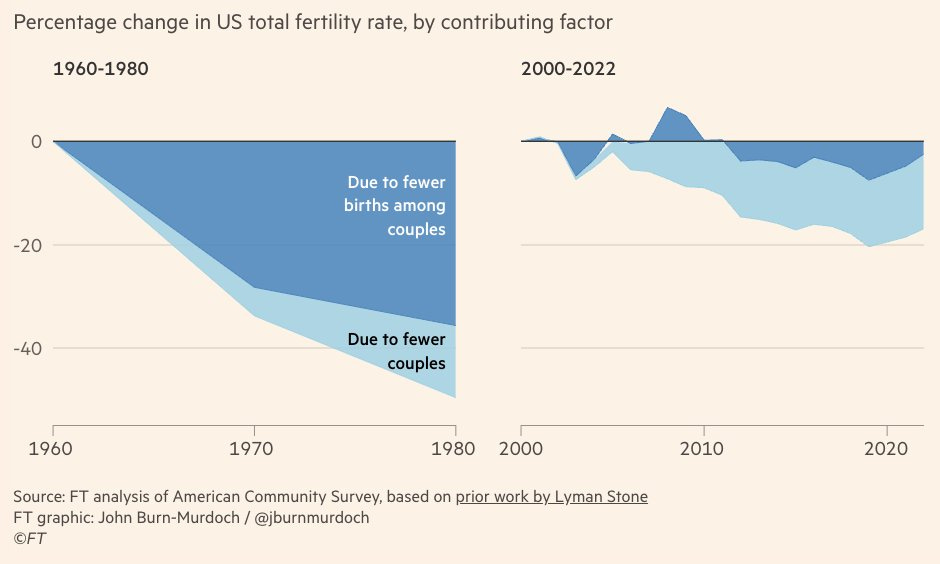

Historical declines looked different. From the 1960s, US fertility fell primarily due to fewer births among couples. In that context, baby bonuses might raise fertility. But today, the major contributing factor is the decline of coupling.

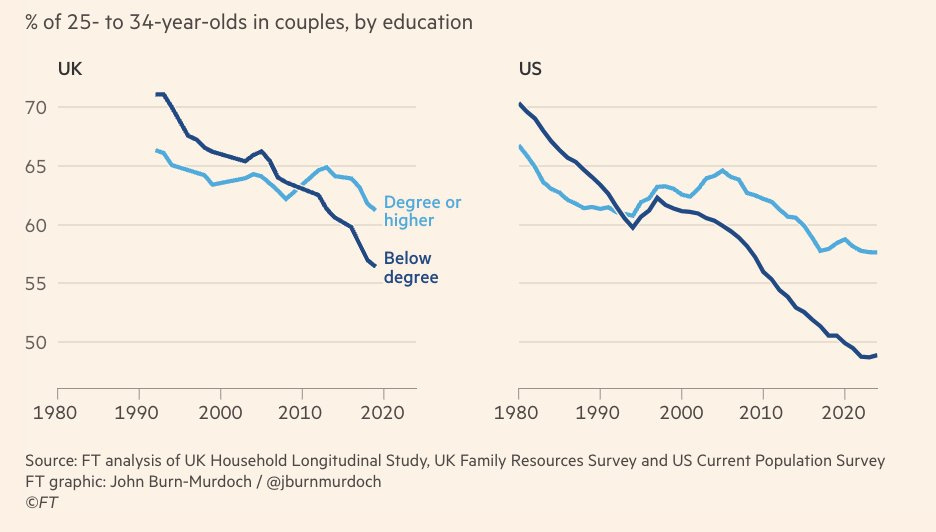

Slurs of ‘childless cat ladies’ usually target female graduates, but in the US, Sweden and Finland the real decline is happening among people with less education.

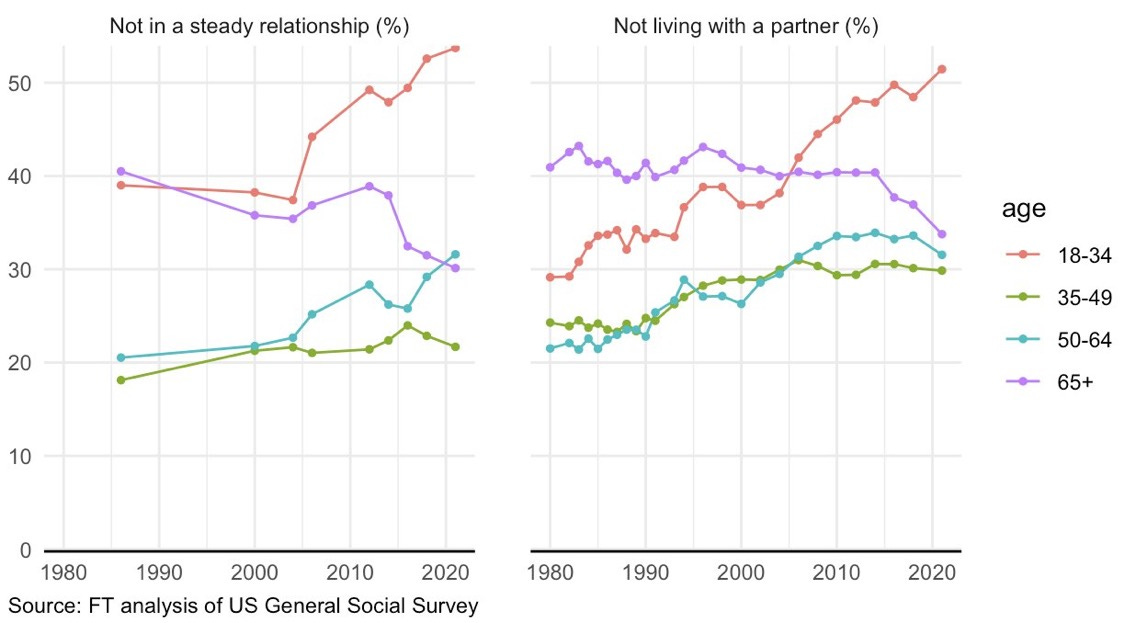

In the U.S., over half of 18 to 34 year olds are neither in a steady relationships nor living with a partner. Most single people don’t even feel much pressure to find a partner. Half say they are not even looking.

In societies where men and women’s earnings are converging and cultural obligations are fading, relationship formation increasingly depends on LOVE! As singledom rises, it becomes broadly accepted. Free from stigma and economic dependency, people can be more selective about their partners.

Yet compatibility can prove elusive. Men and women who are shy, introverted, boring, aggressive, violent, manipulative, deceitful, unfaithful, or ideologically polarised may ultimately call it quits. The sources of friction are wide-ranging - from personality mismatches to ideological divides. And after perennial disappointments, some may opt out. Without a loving partner, they may hesitate to procreate alone.

The big shift is not childless couples, but the rise of singles:

“Single adult households without children experienced the fastest growth rate of 21.0% [from 2013-2023]. Households made up of couples (according to the legal marital status or de facto relationship) without children increased by 5.9 %”.

Back in 2016, 50% of all Swedish households were single persons. If people are not in stable relationships, they may be reluctant to procreate. In Sweden, male fertility is much lower among those who performed poorly in cognitive tests, earnt less, or were obese. These men’s biggest challenge is not so much the cost of childcare, but the dating market.

In South Korea, the share of never married precisely tracks the rise in childlessness. In China and the United Kingdom, both marriage and fertility are falling. If people are not forming loving, committed relationships, they may be reluctant to take on major financial and emotional responsibilities. Instead they get cute puppies!

Personalised Online Entertainment

The rise in singles coincides with another major trend: the explosion in personalised online entertainment. Smart phone ownership has skyrocketed globally.

Let's rewind to the early 2000s - those neanderthal years when peak mobile entertainment was chasing pixels around a screen. With such dismal alternatives, the most fun you could have was hanging out with friends. Before we were old enough for pubs, my classmates came over to play Nintendo 64 or hang out in my garage. I’d sweep the concrete floor and arrange plastic chairs, we'd banter and make little jokes. Classy? No. Teasing, toying and general tomfoolery? Absolutely.

Today, my invitations would face stiff competition! Binge on Netflix, the Premier League, Black Pink’s livestream, sports gambling, or the delights of PornHub.

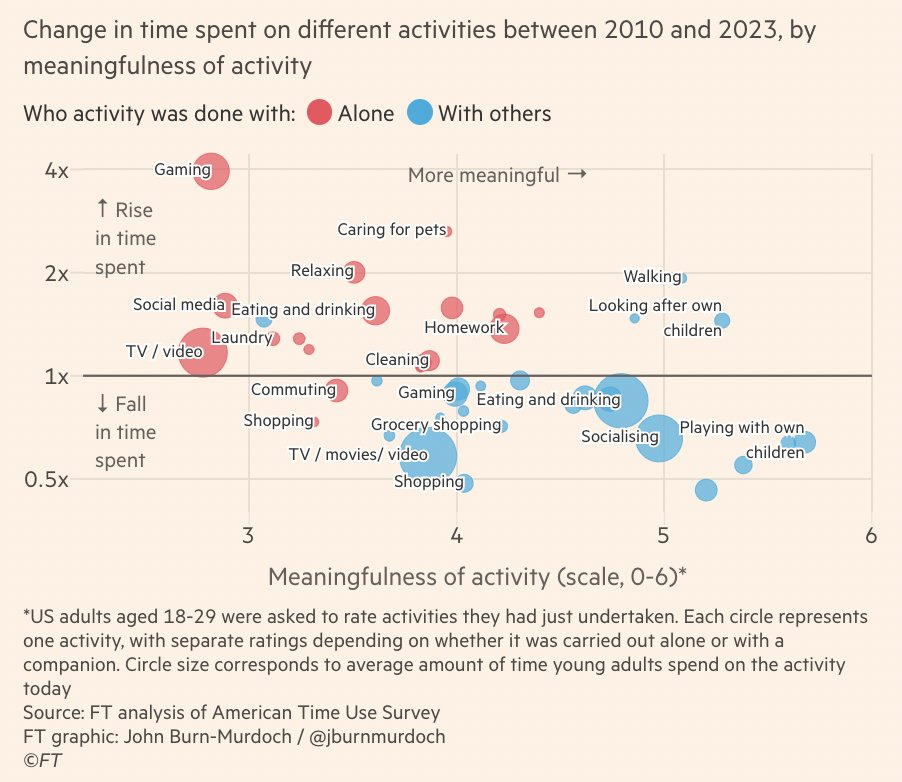

Why venture out when everything – from Deliveroo to Netflix to Zoom meetings – arrives at our doorstep? Smartphones deliver endless streams of hyper-engaging media sometimes eclipsing the appeal of face-to-face connection. Between 2010 and 2023, US young adults spent 4 times more hours gaming.

Coordination failures come into play: staying home alone loses its stigma; and even if one wants to socialise, no one else is going out. This risks generating a self-reinforcing cycle whereby people do not necessarily develop social skills or confidence.

All the available evidence points to growing isolation. Young people are spending much more time alone. 65% of young American men say “no one knows me well”. 28% of Gen Z men didn’t socialise with anyone (who they didn’t live with), in the past week, and 65% say “no one knows me well”.

According to GWI (a global consumer research company, surveying internet users aged 16+), East Asians and Europeans report using social media for 1.5-2 hours daily, while Brazilians, Mexicans, Filipinos, Saudis and South Africans report at least 3 hours every day. In the US, 66% of men say that they wish they spent less time on their phone.

A meta-analysis of 33,831 participants across 24 countries found concerning levels of 'problematic smartphone use' - defined by withdrawal symptoms, loss of control, and neglect of other activities. In China, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia, 30% of young adults score above clinical thresholds. Even in France and Germany, 20% report struggling to control their use.

My suspicion is that massive improvement in quality of online entertainment crowd out socialising and development of social skills, possibly hurting relationship formation as well as desire for children within marriage. This is merely a hypothesis, which fits with the global timing and pattern. Personal online entertainment (sports bets, video games, podcasts, TikTok) are so engaging, they may be outcompeting real-world interactions.

Going forward, we need rigorous research exploring how intensive parenting pressures, relationship frictions, and digital entertainment might be reshaping family formation - ideally exploiting natural experiments or exogenous shocks.

Beyond the global trend, there may also be some regionally specific frictions.

China: Digital Retreat and Cultural Liberalisation

China's marriages have hit rock bottom - with only 6.1 million weddings in 2024. By 2020, only 67% of Chinese women were married, down from 80% in 1990. My interviews with young Chinese people suggest three key drivers.

First, cultural liberalisation has made singledom more permissible, while status remains firmly tied to economic success. Given inadequate pensions, parents now raise their daughters for economic autonomy.

Second, online connectivity enables young women to celebrate independence. On platforms like "Xiaohongshu," young women take the term 'wanghong' (online celebrity) to raise the prestige of singledom, crafting sophisticated "living alone" vlogs showcasing pretty apartments, fitness routines, and evening rituals. Brands are taking note - increasingly adopting the slogan ‘Live for yourself’.

Third, both genders seem to be retreating into digital worlds. China’s domestic video game sales reached $45 billion in 2024, with mobile games making up 73% of the total. One interviewee was explicit,

‘The unprecedented development of social networks and entertainment has made young people less interested in finding a spouse’.

MENA: Gender Segregation and Divorce Permissibility

The Middle East, North Africa and Anatolia are witnessing a rapid decline in coupling and fertility, which seems surprising given persistent religious conservatism. Attitudinal surveys indicate strong religiosity, frequent religious attendance, daily prayer, and strong support for gender segregation. Female employment is around half the global average, just 16% in Egypt. Hardly a hotbed for liberalism.

MENA societies historically consolidated trusted networks through cousin marriage. But over the past 50 years, there has been a massive decline in fertility, resulting in fewer cousins of suitable age. With fewer eligible cousins, MENA marriages are increasingly based on personal choice.

Given religious ideals of gender segregation, dating is tough. This creates a unique tension: gender segregation makes it difficult to find deep emotional compatibility.

Divorce is also permissible in Islam. In 2000, Egypt introduced no-fault divorce for women. Unlike Muslim Pakistanis, educated and urban Arabs increasingly marry non-relatives. Divorcing non-kin doesn't necessarily threaten family loyalty, clan strength, or economic networks.

In MENA, it's tough to find someone you like, yet relatively easy to exit. Together with online distractions, this may be driving marital delays and reducing the reproductive window.

The Educational Arms Race and Childcare Costs

Economic factors may also help explain why some couples stop at one or two children. In South Korea and Hong Kong, interviewees repeatedly stressed the costs of intensive parenting and the gruelling educational arms race. As Sophie explained:

“In Hong Kong, raising up a kid really takes a lot of money. I think two kids are ideally the best because they can learn from each other, but in Hong Kong, it’s so stressful… The application processes are so stressful. I could only go through that stress once. I just want to give him or her the best that I have. I have limited resources, and I want to give everything I have to my kid.

Everyone wants to get into the best school… You want kids to get into the best school, because your peers are doing the same. And there are interviews, not just for the kids, but for the parents. They want to know what background the parents are from, and what they do..

Even for kindergarten application, they have to make a video of the kid... Making that video takes a lot of time. And it’s very stressful.

At local primary school, you have to pay for lessons: piano lessons, violin lessons. Even if you know how to play piano, that’s not sufficient, you have to be special and standout. They have to play the violin, the harp. And these kinds of lessons are not cheap. And the kid would be stressed as well.

At middle school, it starts to get very intense. The grades start to get very intense. In Hong Kong, there are not a lot of universities that are recognised. People just want to get into the four big universities that are recognised. It’s quite competitive”.

Thinking BIG and Building Bridges

To crack this puzzle of plummeting fertility, social scientists might rethink how we build and test theories:

Better data. A central database of fertility - which is accurate, global and updated frequently - would be wonderful.

Qualitative research provides useful insights into what young people want, pathways to prestige, why relationships fracture, and expressed reasons for fertility choices.

Rigorous quantitative studies might leverage natural experiments and exogenous shocks, to ascertain the causal impact of plausibly global drivers.

The most compelling theories of collapsing fertility will be able to explain and provide evidence of how global and country-specific factors interact to shape fertility dynamics.

Invest in relationship capabilities. Austerity in the UK has heralded widespread closures of youth centres. Potentially, this may have cut spaces to build community and friendships. Going forwards, I’m curious to see more research on how schools might help students strengthen their emotional intelligence and social skills, ultimately becoming more charming, fun, empathetic and supportive. Down the line, this might strengthen happy relationships - which are increasingly a precursor to fertility.

None of this can be solved in disciplinary silos. Diverse collaborations are essential to address the fastest demographic shift in human history.

In this vein, check out my two podcasts with Jesús Fernández-Villaverde and also with John Burn Murdoch.

My Essays on Fertility

Macroeconomics

Relationship frictions

What Prevents & What Drives Gendered Ideological Polarisation?

Ghosting the Patriarchy: Female Empowerment and the Crisis of Masculinity

Intensive parenting and the educational arms race

What caused East Asia's rapid fall in fertility? (over the 1960s and 70s)

Fertility is a collective action problem. Can it be tackled with taxation?

I don't see how huge drops over the course of a decade can be anything but smartphones. Gender attitudes, levels of environmental toxins, etc. couldn't change fast enough (and simultaneously across countries, no less) to produce that outcome.

Wouldn't it be useful to have more disaggregated data, like a time series for "annual birth rates in among 24-year-old women" in each Nigerian state? That would allow you to identify natural experiments (different timing of introduction to smartphones, based on where the networks rolled out and when) which could test the hypothesis more rigorously.

If you believe that we have far more people on this planet than is ecologically sustainable, then falling fertility rates is an unmitigated good, regardless of slower growth in per capita GDP. We have plenty of wealth, the problem is distribution. How you frame this development is as important as doing careful research. I’m totally in agreement that there’s a lot of unfounded speculation.