Breaking Barriers, Building Nations: The Power of Neighbourhood Diversity!!

Imagine two neighbourhoods: one comprising ethnic enclaves, the other a vibrant blend of diverse cultures. Which has stronger social trust and shared identity?

Two fascinating studies have cracked open this question, examining the long-run effects of dramatic shifts in neighbourhood composition:

Bazzi, Gaduh, Rothenberg, and Wong dive into Indonesia’s ambitious Transmigration program - a massive social experiment that created new settlements with a kaleidoscope of ethnic diversity.

Abramitzky, Boustan, and Connor take us to New York’s bustling Lower East Side, where the Industrial Removal Office played urban alchemist, dispersing Jewish immigrants across America’s melting pot.

Ten thousand miles apart, they arrive at a common conclusion: neighbourhood diversity fosters integration.

So, saddle up and let’s dive in (or am I mixing metaphors?).

Afterwards, I’ll share broader reflections on what this suggests for government action and integration.

The Indonesian Transmigration Study

With over 700 ethnolinguistic groups spread across thousands of islands, Indonesia faced significant challenges in forging a unified national identity.

The Transmigration program, while primarily aimed at population redistribution and development, was also seen as a tool for nation-building. By mixing people from different ethnic backgrounds in new settlements, policy-makers hoped to strengthen Indonesian identity.

From 1979 to 1988, the Government relocated two million ethnically diverse migrants from the Inner Islands of Java and Bali to hundreds of newly created agricultural villages in the Outer Islands. This was one of the biggest resettlement programmes in human history. It was of course hugely controversial, often usurping indigenous communities.

Samuel Bazzi, Arya Gaduh, Alexander D. Rothenberg and Maisy Wong have an absolutely fantastic paper, studying its long-run effects.

Now here’s the twist,

Rushed program implementation meant that village assignments were quasi-random. Migrants couldn’t choose their destinations and were just assigned based on arbitrary arrivals at transit camps.

Mixing It Up: The Housing Lottery

When settlers arrived in their new villages, they didn’t get to pick where they lived! Instead, the government used a lottery system to assign housing and farm plots.

This lottery limited residential segregation and inequality in land quality across ethnic groups. It’s like the government was playing a giant game of social Tetris, trying to create a perfectly mixed community from the get-go.

Social engineering was not 100%, however. “The haphazard resettlement process generated significant variation in diversity even across nearby settlements with similar natural advantages”, explains Bazzi and colleagues. Inadvertently, some neighbourhoods became highly ‘polarised’ (comprising two big ethnic groups), whereas others were more ‘fractionalised’ (featuring multiple small ethnic groups).

This initial random assignment had long-lasting effects. Even decades later, this initial mixing significantly reduced the level of ethnic segregation within villages.

Cue an Economist’s delight: a natural experiment on the impact of ethnic diversity!

🥳🎉🎊

Bazzi and colleagues theorise that when multiple ethnicities all in inhabit the same village, they may have more incentive to adopt a shared language and national identity. Whereas in ‘polarised’ villages (inhabited by two large groups), people tend to stick with their own.

Big, powerful groups can develop their own institutions and club goods, which reward members, thereby encouraging in-group loyalty. If people trade and collaborate with co-ethnics, they may view outsiders with suspicion, and resist national integration.

To test this, Bazzi and co. regress various nation-building outcomes on diversity (measured in terms of both fractionalisation and polarisation) in Transmigration villages. They have a host of controls; nerds can check the paper for details..

To assuage concerns about endogeneity, Bazzi and co. use a range of descriptive statistics and a cunning instrumental variable (see page 3998, the IV and OLS results are very similar).

They then examine long-run effects on culture, namely:

Intermarriage rates

Ethnically distinctiveness of children’s names

Social capital and trust measures from survey data

Public goods provision and conflict at the village level

Here’s what they find…

Neighbourhood diversity fosters national assimilation

Fractionalised villages, with many small ethnic groups, show greater adoption of the national language, more inter-marriage, and less ethnically distinctive names.

A one standard deviation increase in neighbourhood diversity leads to a 12.9 percentage point increase in Indonesian use at home.

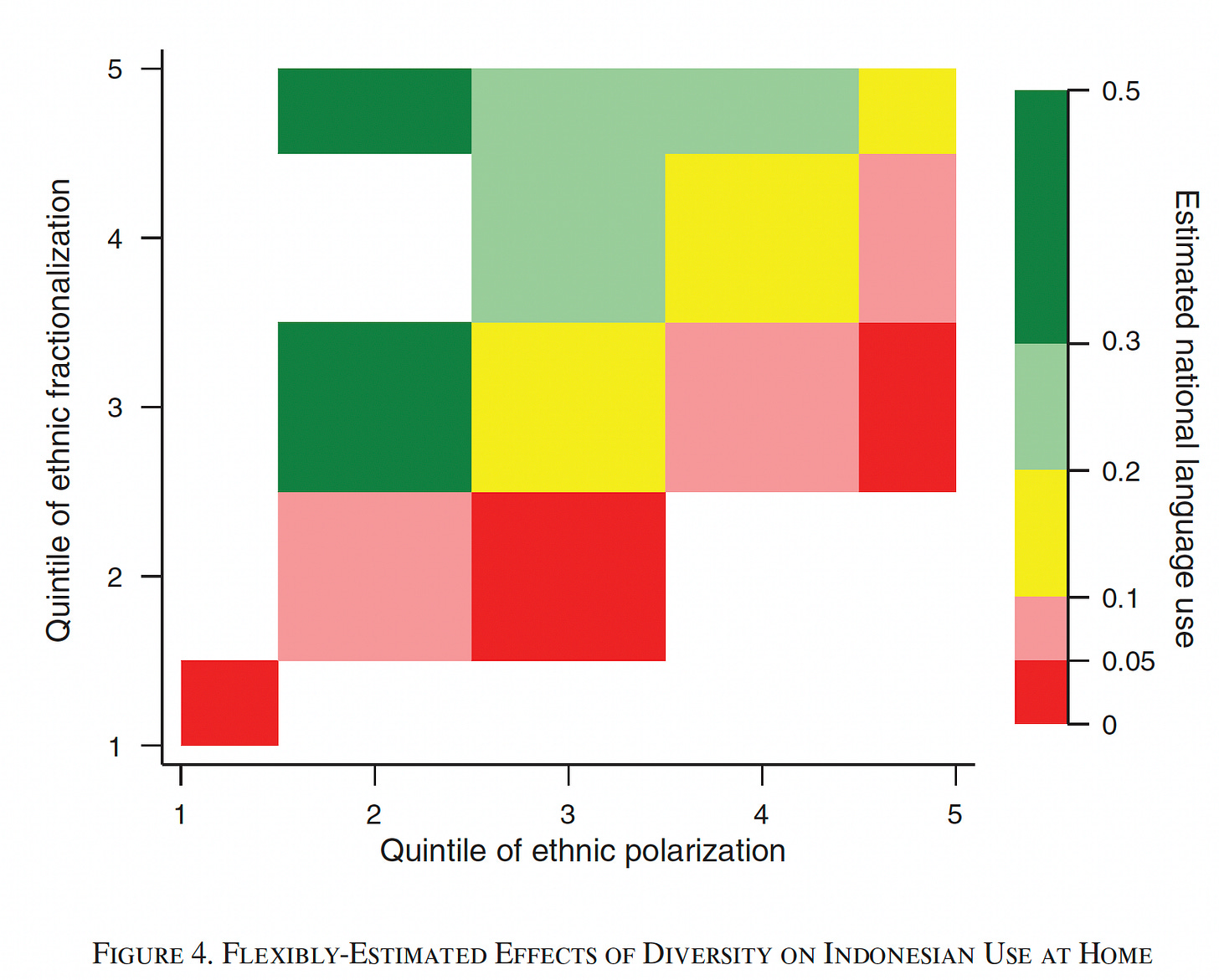

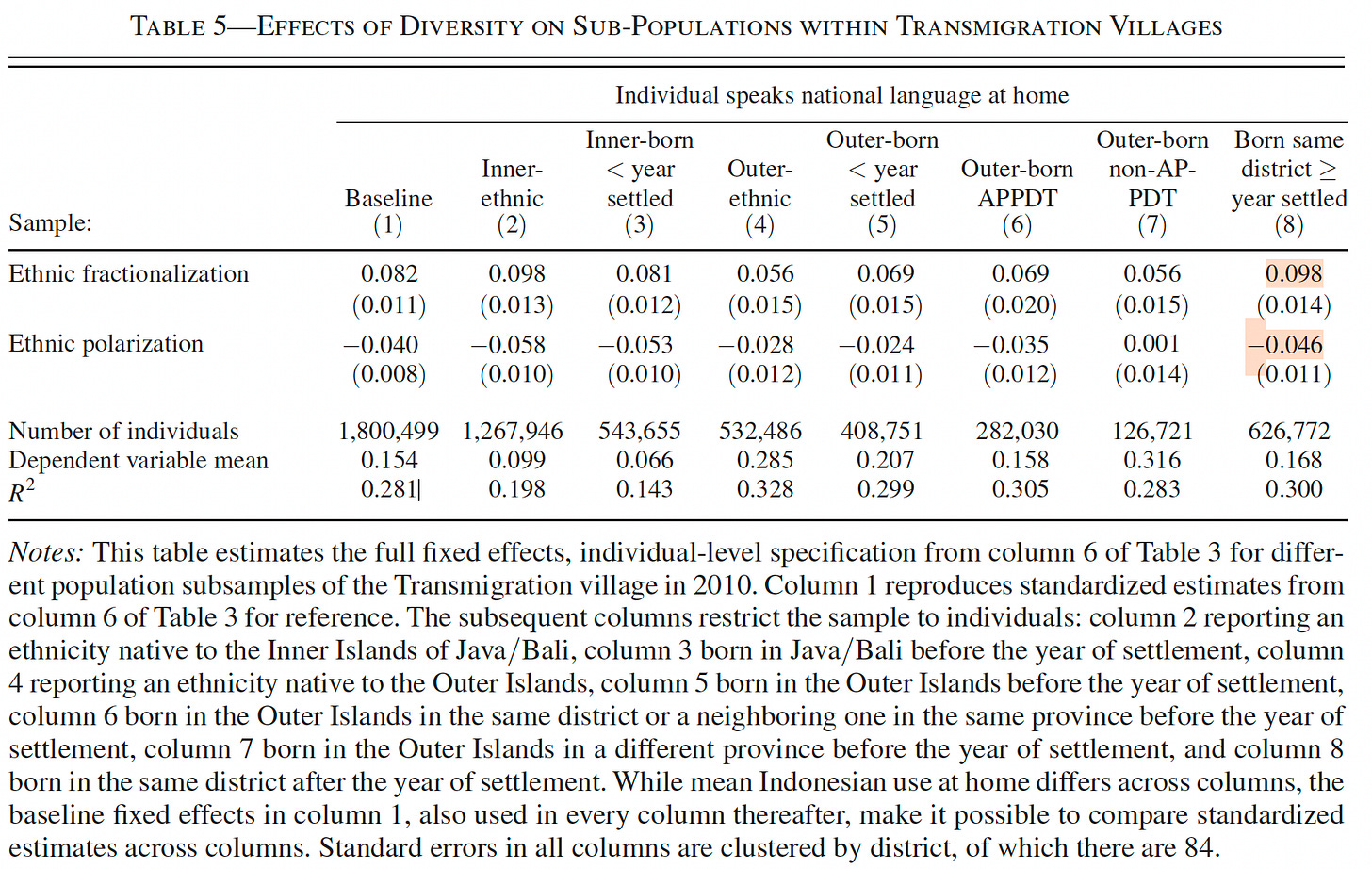

Table 4 and Figure 4 show that residents of fractionalised villages are more inclined to use the national language at home.

Indonesians who were born in the year of resettlement and grew up in ethnically fractionalised villages are more likely to speak the national language at home.

Children who grew up in households speaking Indonesian at home showed weaker ethnic attachment and greater openness to integration as adults. Intergenerational persistence!

Conversely, polarised villages (with a couple of large ethnic groups) exhibit less use of the national language, lower intermarriage, and more ethnically distinctive names.

A one standard deviation increase in neighbourhood dominance leads to an 8 percentage point decrease in Indonesian use at home.

Speaking Indonesian at home isn’t about Economics, but Identity!

One might think that the adoption of the national language at home is Econ 101 - improving fluency for future labour market returns.

However, when Bazzi and colleagues looked at the effects of village diversity on Indonesian language use across different education levels, they found a remarkably consistent pattern. Whether people had no schooling or post-secondary education, the effects of fractionalisation (many small groups) and polarisation (a few large groups) on language use were strikingly similar.

These findings indicate that the choice to speak Indonesian at home isn’t just about economics.

It’s about IDENTITY.

In diverse communities, people are choosing to adopt the national language as a way of connecting with their neighbours and expressing a shared national identity.

Local Contact Matters!

Bazzi and colleagues examine diversity effects at different levels - from the broader village down to the neighbourhood and even next-door neighbours. This allows them to disentangle the effects of overall village diversity from more localised contact.

The effects of diversity are strongest at the neighbourhood level and even between immediate neighbours, highlighting the importance of everyday interactions. Having both immediate neighbours from different ethnic groups increases the likelihood of speaking Indonesian at home by 19.1 percentage points. 🇮🇩

This really drives home the importance of day-to-day contact. It’s not just about living in a diverse village; it's about who you interact with on a daily basis that shapes your language choices and, by extension, your national identity.

Segregation Hurts National Integration!

Bazzi and colleagues don’t just look at overall village diversity – they also examine how ethnic groups are distributed within villages. They use a sophisticated measure of segregation that captures how unevenly ethnic groups are spread across neighborhoods within a village.

What do they find?

Segregation is a really big deal.

In more segregated villages, both the positive effects of fractionalisation and the negative effects of polarisation on national language use are muted. For real integration to happen, different ethnic groups need to actually live side by side and interact in their daily lives.

Even if the village as a whole is diverse, if ethnic groups live in separate enclaves, they’re less likely to integrate. As the authors explain,

These findings have really important implications for policies on integration. Simply creating diverse communities isn’t enough – the spatial distribution of different groups within those communities also matters.

For villages to become integrated, different ethnic groups need to actually live side by side and interact in their daily lives.

Ethnic diversity encourages inter-marriage

Fractionalised villages show higher rates of inter-marriage, even after adjusting for supply. This is consistent with the hypothesis that diverse intermixing encourages integration.

Ethnic diversity encourages out-group naming!

Parents living in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods are less likely to give their kids names from their own ethnicity.

Yet in polarised villages (with two rival ethnicities), out-group assimilation is rare.

Diversity promotes social capital!

Drawing on the 2012 National Socioeconomic Survey, Bazzi and colleagues find that in polarised villages, individuals are:

less tolerant of non-co-ethnic activities in the village

feel less safe, and

If communities are polarised and do not integrate, they tend to be characterised by distrust. This is often associated with ethnic animosity and conflict.

Diversity encourages votes for ‘Pancasila’ parties!

Fractionalised villages are more likely to vote for parties that embrace the Indonesian state ideology of ‘Pancasila’ (‘Unity in Diversity’).

This paper is hugely important. It persuasively demonstrates a plausible hypothesis: when a village has two big rival groups, each sticks with their own. But when there are many different groups, they assimilate, intermarry, and embrace shared identities.

BRAVO Bazzi, Gaduh, Rothenberg, and Wong!

Do you know about Indonesia’s ‘Rainbow Village’?

SEGUE, NOT IN THE PAPER..

Residents of Kampung Pelangi, a village in South Semarang, used community money to paint their houses a spectrum of colours! 232 buildings were transformed by residents, builders, and even the town mayor.

It certainly embodies the national motto of ‘Unity in Diversity’!!

A complementary study by Abramitzky, Boustan, and Connor examines the opposite scenario: what happens when individuals leave ethnically concentrated enclaves?

The Industrial Removal Office Study

In the early 20th century, New York’s Lower East Side was one of the world’s largest Jewish communities. Immigrants from Eastern Europe crowded into tenements, creating a vibrant but often challenging living environment.

The Industrial Removal Office (IRO) program aimed to alleviate overcrowding and encourage assimilation by helping families move to other parts of the country. 39,000 Jewish households were funded to leave the densely populated, predominantly Jewish neighbourhoods of New York City and settle in more integrated environments across the United States.

Ran Abramitzky, Leah Boustan, and Dylan Shane Connor Abramitzky and colleagues employed several innovative methods to analyse the effects of leaving ethnic enclaves.

Quick pause for visuals:

Here’s what they do:

Novel historical data: They digitised and transcribed original IRO records from the American Jewish Historical Society, including information on participants’ names, ages, occupations, and addresses prior to relocation.

Geolocation of historical addresses: They mapped IRO participants’ original addresses to 1910 census enumeration districts, allowing for precise neighbourhood-level analysis.

The ‘Jewish Names Index’. To overcome the challenge of identifying Jewish people in historical records (the census didn’t record religion), they created an index based on the relative probability of a name being associated with Yiddish or Hebrew speakers in the 1920 and 1930 censuses.

Comparison group construction: The authors identified a comparison group of non-participating Jewish households living in the same initial neighbourhoods and holding the same occupations as IRO participants.

Longitudinal data linkage: They linked IRO non/ participants in the 1920 census with linked their sons in the 1940 census, to study intergenerational effects.

Duration of exposure: To account for potential unobservable differences between participants and non-participants, the authors compare outcomes within the IRO program based on years of exposure to life outside enclaves.

Analysis of return migration: The study examines who chooses to return to New York City after participating in the IRO program, providing insights into the pull factors of ethnic enclaves.

The Benefits of Integration!

The study revealed several key findings about the effects of leaving ethnic enclaves:

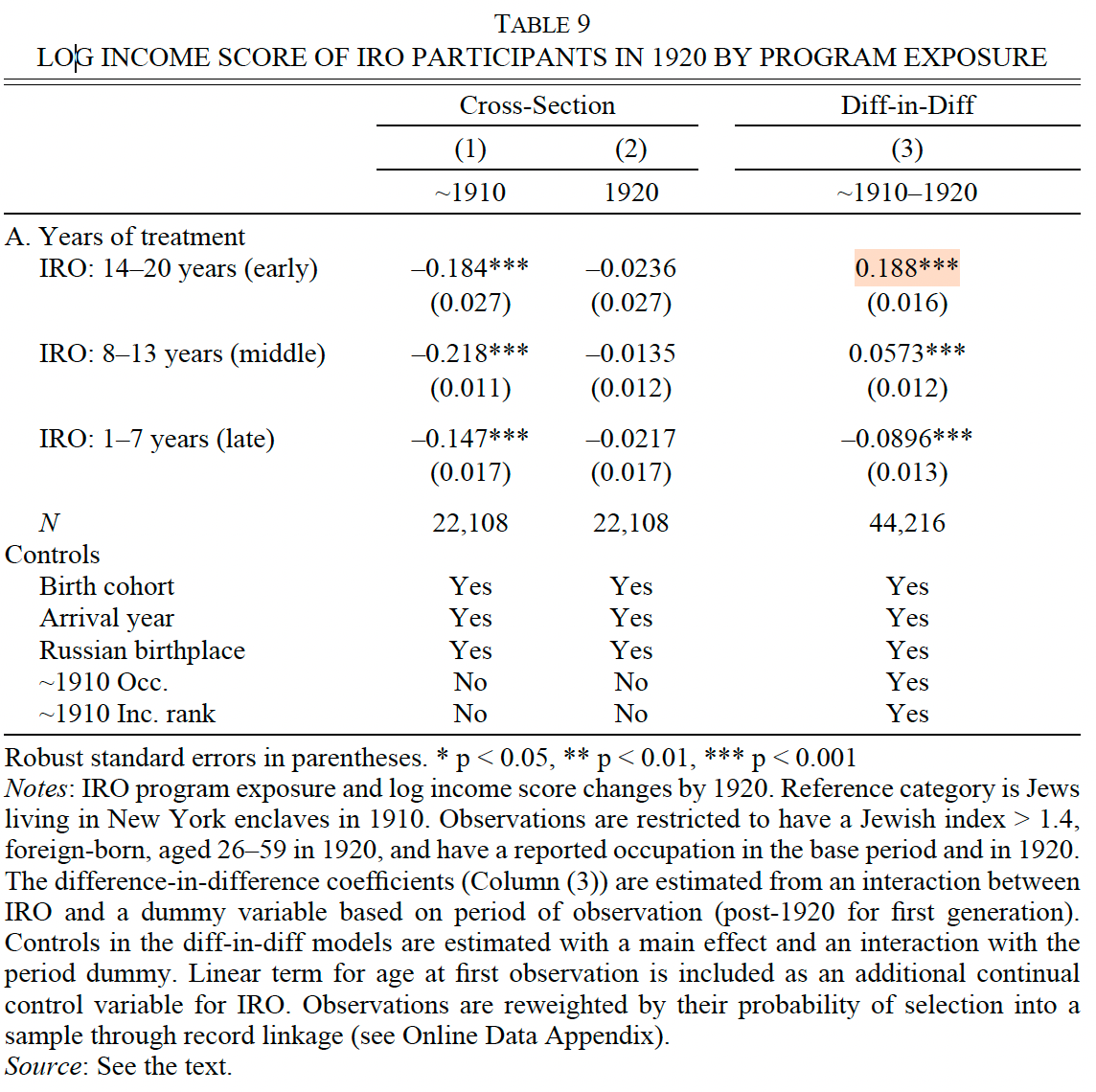

IRO participants started off earning about 18% less than their neighbours with the same occupation. This suggests the program was indeed helping those who were struggling economically.

By 1920, about 10 years after relocation, IRO participants had nearly caught up with the comparison group. The initial earnings gap had been almost entirely erased.

After controlling for initial occupation and placement in the initial income score distribution, IRO participants were actually earning 4.4% more than their counterparts who stayed in the enclave.

Economic gains increased with more years spent outside of an enclave.

Intergenerational mobility

Sons of IRO participants earnt 6% more than sons of non-participants in 1940. The IRO program weakened the relationship between a father’s initial economic status and his son’s later outcomes. This suggests that leaving the enclave allowed families to ‘reset’ their economic trajectories, providing new opportunities for the next generation.

Occupational shifts

IRO participants were less likely to work in manufacturing, more likely to be self-employed and to work in professional or managerial roles.

Language Acquisition and Citizenship!

Participants were also more likely to speak English, indicating greater linguistic integration into broader American society.

They were more likely to become homeowners and to have received citizenship by 1920. 🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸

Inter-marriage

IRO participants were more likely to marry spouses with less Jewish-sounding names, indicating increased social integration!

That said, IRO participants did not give their children less Jewish-sounding names, suggesting they maintained aspects of their cultural identity.

Selective return migration

Men with more Jewish-sounding names were more likely to return to New York City, potentially to access cultural amenities and social capital in Jewish enclaves.

This is unsurprising: people with strong religious identities may prefer to live with like-minded others.

The message is clear: by leaving ethnically concentrated enclaves, Jewish immigrants achieved greater economic mobility and social integration.

Bravo Ran Abramitzky, Leah Boustan and Dylan Shane Connor!

Diverse neighbourhoods can encourage integration!

These fantastic studies highlight the crucial role of neighbourhood composition in shaping cultural integration and economic outcomes. When diverse groups live side by side, they are more likely to assimilate and adopt a shared language. In the U.S. context, this integration also led to positive economic effects that persisted across generations.

This pattern is not unique to Indonesia and America. A growing body of evidence suggests that population mixing fosters cultural change. China’s Sent Down Youths programme and Stalin’s forced resettlements both resulted in intermingling and cultural change.

Conversely, my own research in Zambia and Cambodia revealed that social change occurs much more slowly in physically isolated, homogeneous communities. If practices are widespread, they may be taken for granted and widely accepted. Even if individuals are privately critical, they seldom see dissent or deviation, so quietly conform in order to maintain respectability.

Now here’s a serious ethical quagmire:

People may genuinely prefer to live alongside co-ethnics, who provide valuable club goods: men with very Jewish names returned to New York City. However, as we have seen, this can suppress their own earnings, intermarriage and national integration.

So perhaps it is not surprising that all this social engineering - in New York, Indonesia, China and the USSR - were facilitated by strong, bold government action. Singapore also stands out for mandating neighbourhood ethnic diversity.

Another complication is that in the 21st century, where everyone is glued to their phones, online networks may be just as important as spatial segregation? That’s an open question.

But my takeaway is that neighbourhood diversity builds national trust and cohesion.

Further Reading:

Alice Evans, “Cities as Catalysts of Gendered Social Change? Reflections from Zambia”

Alice Evans, “How Cities Erode Gender Inequality: A New Theory and Evidence from Cambodia”

Every time I read one of your essays, I walk away a little bit smarter. So thank you for that, Alice!

As everything does, this once again reminds me of the Caribbean, where also people of many different ethnicities were thrown together, usually not because they chose to live on a particular island, but because that's where they were shipped (as political prisoners, indentured servants, or enslaved people). Similarly here, smaller islands that house more ethnicities seem (at least by my observation) to be more trusting and welcoming of outsiders, and less corrupt.

Very interesting. As I was reading it, I was thinking of the forced relocation programs they're implementing in Denmark, where they basically force immigrants to live in less immigrant-concentrated neighborhoods, in many cases tearing down and rebuilding whole areas.