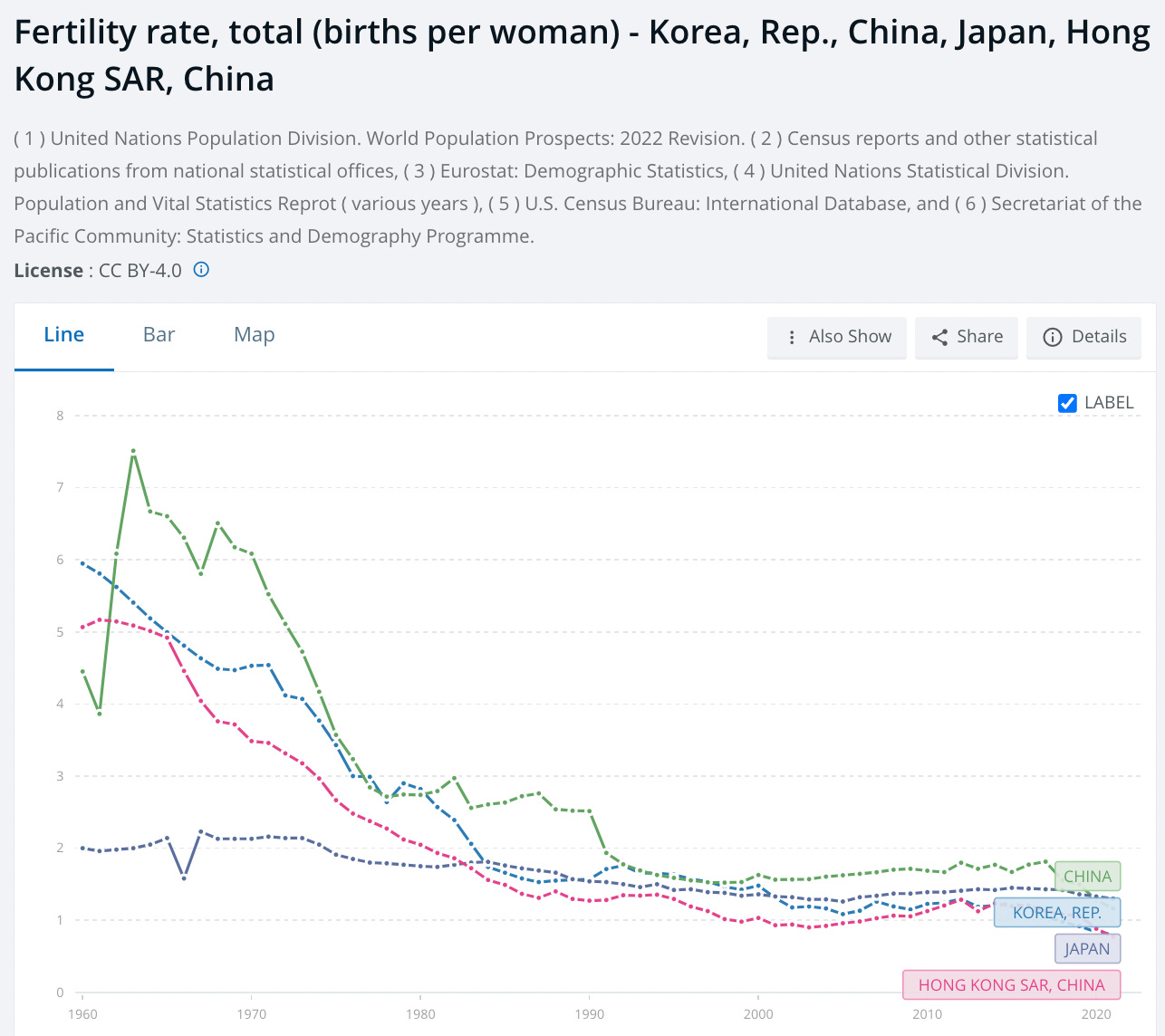

Why has fertility plummeted across East Asia?

Let me suggest 5 major drivers:

Meritocratic civil service exams encouraged heavy investment in education. China institutionalised this first, but the system then spread across East Asia. Education became seen as the pathway for social mobility.

Education fever has spawned an arms race of intensive parenting.

Within China, fertility fell earliest in the more individualist northeast, where there is less onus on lineage.

Economic development has spawned cultural liberalisation, weakening pressure to bear multiple sons.

Given heavy expectations of parenting and cultural liberalisation, one child is increasingly seen as enough.

To understand all these interactions, we need to trace cultural evolution over the past 1500 years. Buckle up.

Imperial examinations

East Asians strongly value education and believe it to be the pathway to social mobility. This may go back to China’s 6th century keju civil service exams. This meritocratic institution has been enormously important - argues Yasheng Huang in “The Rise and Fall of the East”.

The keju provided a meritocratic pathway to respectability. Candidates wrote their answers in a private booth, their answers then were transcribed. Double-blind exams. It was the premium channel to upwards mobility - far more efficient than commerce, religion, intelligentsia and political opposition. This was common knowledge. Stories about commoners being propelled to the elite functioned as an ‘opium of the masses’. The Chinese dream, so to speak.

If you memorised Confucianism, you could achieve great riches.

During the Ming, two to three million men regularly took the qualifying tests. The most intelligent and ambitious men spend years (if not decades) memorising ancient texts. Answers were already established; there was no room for questioning or creativity. The keju system was also adopted in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.

In Korea, the Joseon Dynasty institutionalised and glorified the gwageo imperial examinations (958 to 1894). A family could only be considered noble if one member (from the last four generations) had passed the gwageo and served in government. The crimson certificate was treasured and handed down from generations. Aristocratic status depended on Confucian memorisation.

I suggest that imperial examinations and widespread beliefs in meritocracy spawned ‘education fever’- right across East Asia.

Yes, this was costly, but under Collectivist families socialised children to honour their parents and make their ancestors proud.

High skills at low wages enabled growth

Given East Asian’s belief that education was the pathway for social mobility, they heavily invested in their children’s education. Daughters were sent to factories to fund their brothers’ education.

East Asian economies developed rapidly, partly because their labour force was highly-skilled, but relatively cheap. Education fever thus aided economic growth.

Education fever has spawned an arms race of intensive parenting

Education fever comes with costs; it has generated an intense arms race. ‘Chicken parents’ micro-manage their children’s time-tables to optimise intellectual performance. Competitive investment means that parenthood is seen as extremely costly and labour-intensive.

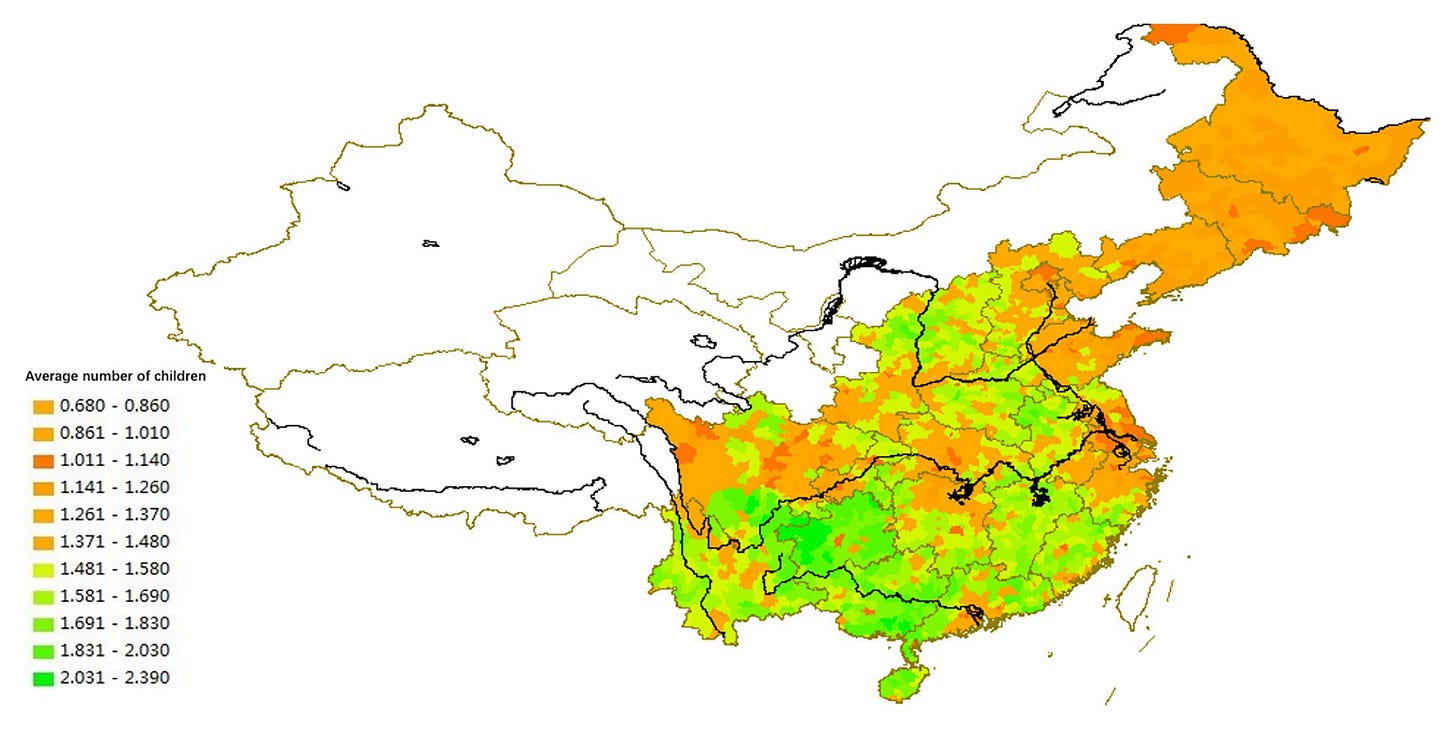

Fertility fell earliest in more individualist regions of China, where lineage was less important.

East Asian families strongly believed in the importance of bearing sons to continue the patrilineal line. This belief was especially strong in China’s south east.

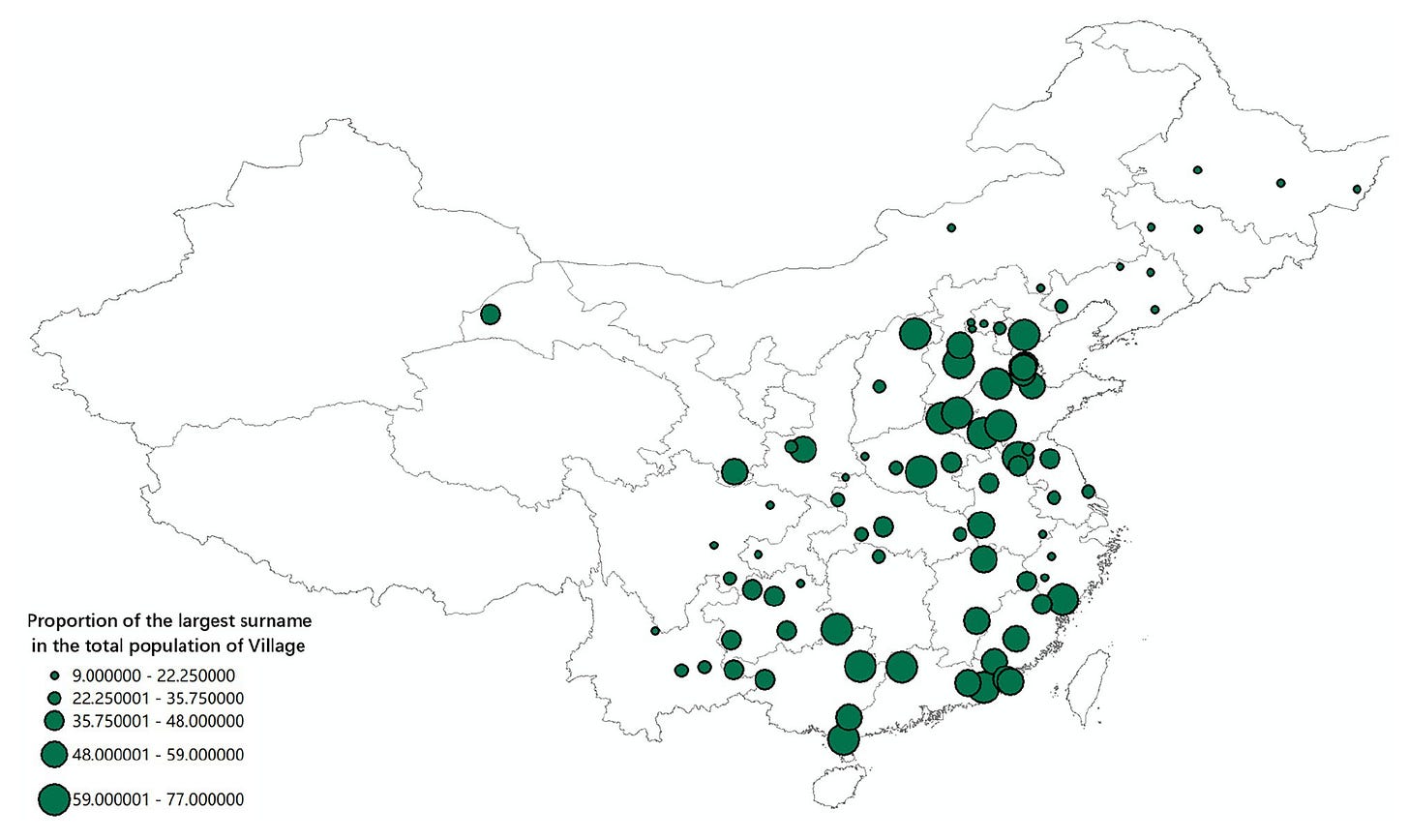

A new paper by Weigang Gong, Meng Zhu, Burak Gürel, Tian Xie reveals a hitherto unrecognised aspect of China’s cultural heterogeneity. They calculate the concentration of surnames in 3000 Chinese counties, as well as the proportion of the top three surnames in administrative villages.

In Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Jiangxi provinces, a single lineage may encompass the entire village. Lineage is extremely important.

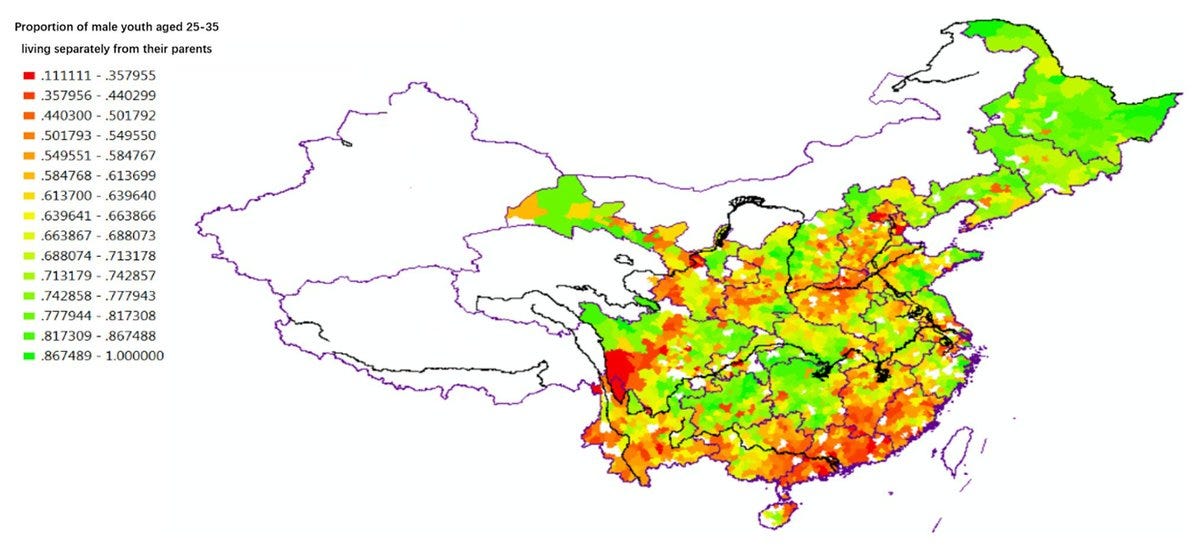

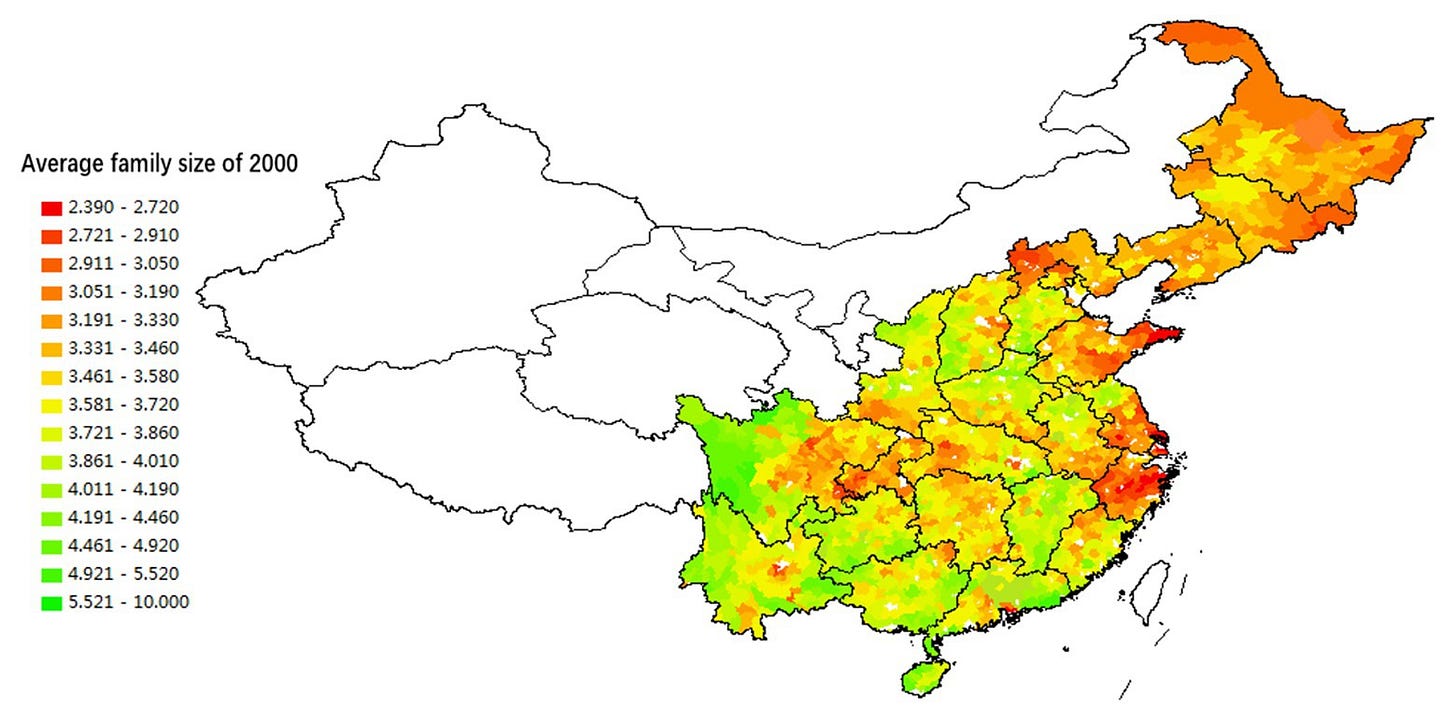

Yangzi River Basin and the Northeast appear to have been more individualist, even in the 1980s, before marketisation and urbanisation. Married men were much more likely to form their own independent nuclear families. In Southern China by contrast, married men tended to remain with their parents.

These patterns persisted in the 1990s.

Households are also much smaller in Northeast China, the Yangzi River Basin, the Jianghan Plain, the Dongting Lake Plain, and the Chengdu Plain. Families tend to break apart.

Lineage development is also associated with higher fertility. In the South, reproduction may be motivated by the moral obligation to bear heirs. Where lineages are less central, there may be far weaker compunction to continue the family line.

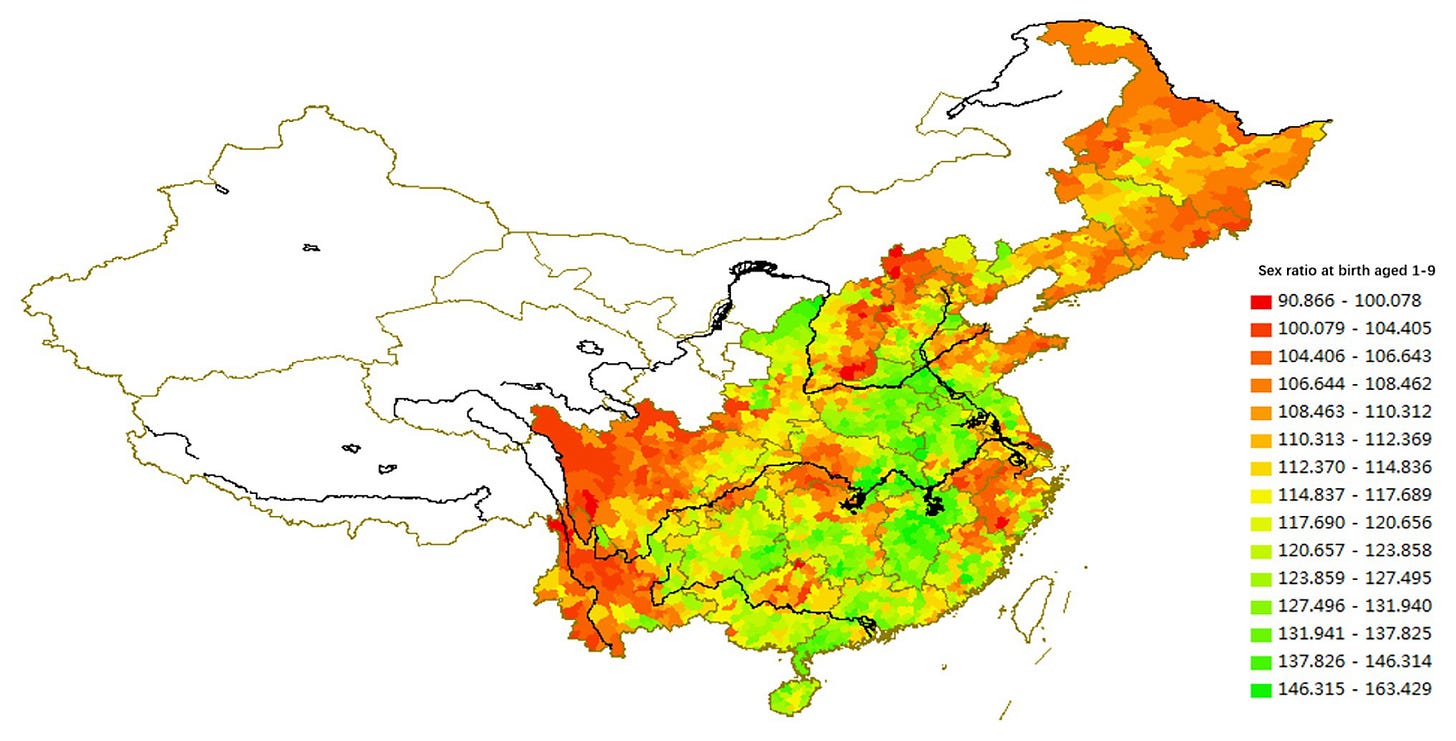

Lineage development is also associated with sex ratio at birth.

This makes sense. If patrilineal lineage is paramount, there should be a strong preference for sons to continue the lineage and worship ancestors.

As you see, the southeast has highest son preference, more collectivism, more multi-generational families, and higher fertility. Yangzi River Basin and the Northeast appear to have been more individualist, even in the 1980s, before marketisation and urbanisation. Married men were much more likely to form their own independent nuclear families.

Economic development has spawned cultural liberalisation and gender equality, weakening the pressure to reproduce more male heirs

East Asia’s economic development has fostered cultural liberalisation and gender equality - as I have previously theorised. As the whole of China becomes more individualistic, there is less social pressure to bear male heirs and continue the lineage. Given high female employment, daughters are increasingly seen as sons because they demonstrate filial piety and provide for their ageing parents.

Moreover, East Asian women can no longer be bullied or shamed into becoming workhorse wombs. As former factory worker turned journalist, Lijia Zhang writes:

"Women have changed. They don't care to be only the reproductive tool of the family or the state".

All this reduces the onus and desire for multiple children.

East Asian fertility has plummeted due to cultural liberalisation occuring alongside education fever

Ironically, the education fever that aided East Asia’s economic development in the 20th century now presents a challenge for development in the 21st century.

Parenting comes with heavy expectations to micro-manage and optimise children’s educational success. Meanwhile, East Asians have also culturally liberalised and become far more gender equal. The pressure to bear multiple sons is now far weaker. As a result, many couples would rather stop at one child.

My theory thus explains why fertility was initially lower in China’s more individualistic northeast, has since fallen in the economically developed and culturally liberalising south east.

Let me add one more suggestion - men. For fertility rates to rise, women need to know that having kids isn't going to kill their careers. That depends on having all-in fathers and partners at home. And workplaces and bosses that encourage men to balance their care responsibilities.

This is far truer in some cultures than others.

Here's a related piece I wrote on this a few years back in FORBES, titled

The Cost of Underestimating the Rise of Women: No Babies

https://www.forbes.com/sites/avivahwittenbergcox/2019/11/24/the-cost-of-under-estimating-the-rise-of-women-no-babies/?sh=3e636648189c