Fertility is a collective action problem. Can it be tackled with taxation?

South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world (0.78 in 2022). ‘Education fever’ has also gripped society: most children attend after-school private tuition (hagwons). Are these two facts connected?

Yes!

Seongeun Kim, Michele Tertilt, and Minchul Yum have a new paper in the American Economic Review showing that parents care about their child’s relative education, compared to their peers. They call this a “status externality”. Competition drives up investment, increasing costs, lowering fertility. But it’s not all doom and gloom. Kim and colleagues think this collective action problem could be fixed - with taxation!

The Basic Facts

The poorest families typically have 1.80 children, while the richest have 2.03. Poorer families are also more likely to be entirely childless.

75% of children are enrolled in after-school programs and with private tutors.

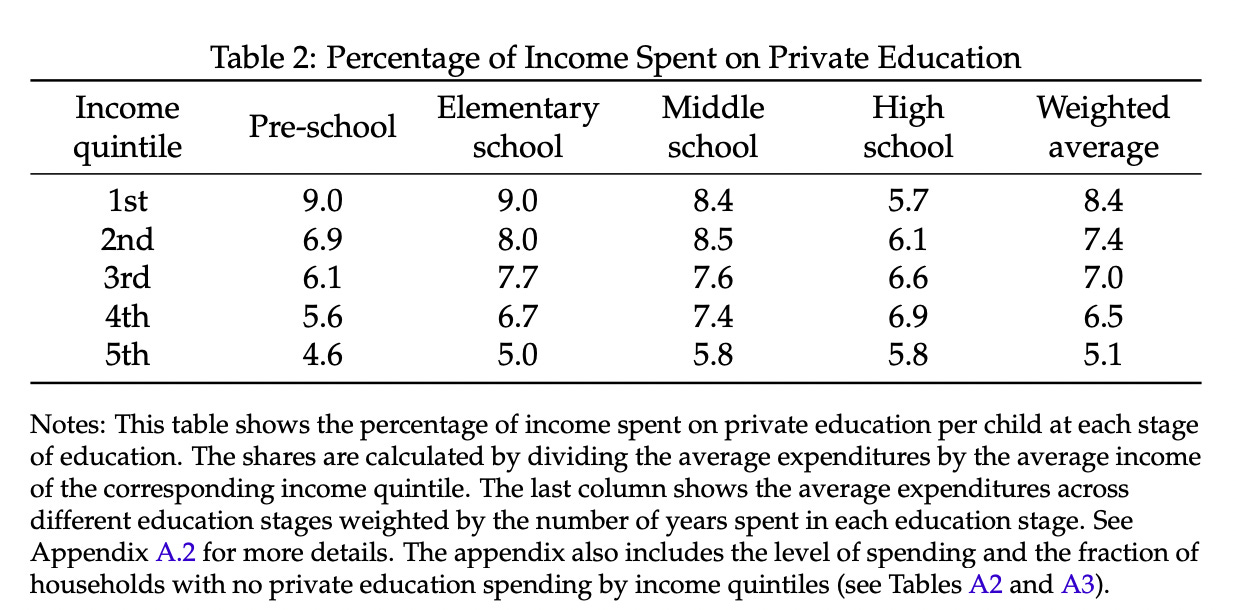

Poorer families typically spend a larger share of household income on private education.

Curfews capped education spending

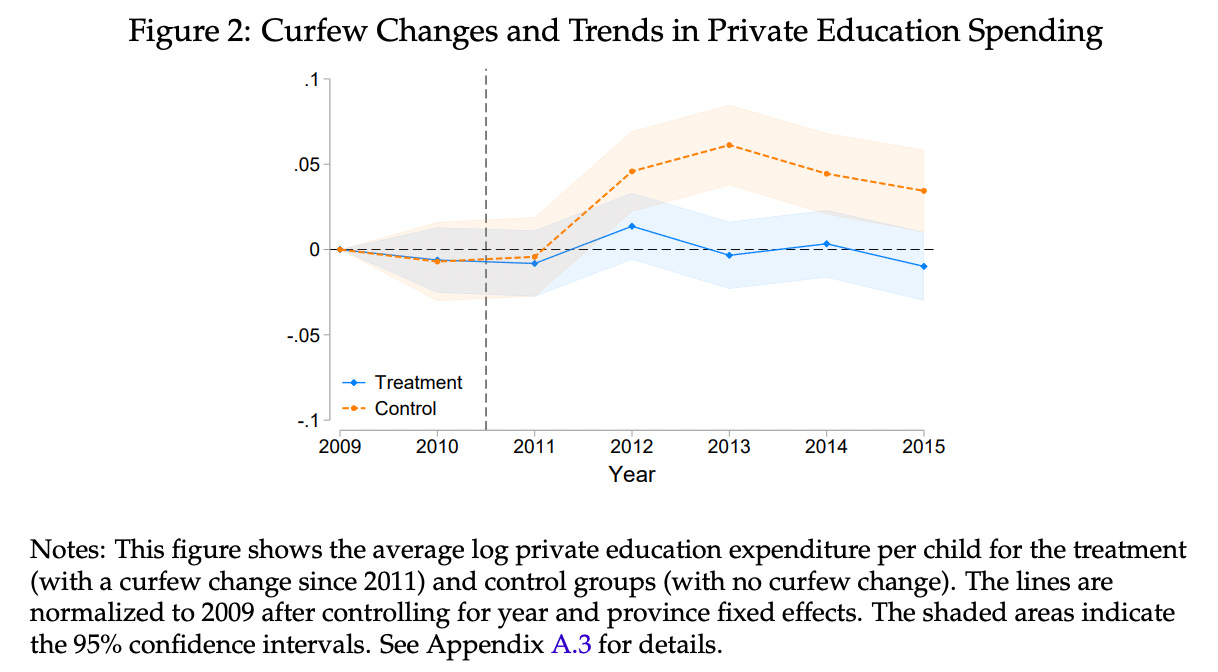

Curfews recently banned private education after a certain time of day (10 or 11pm). This was implemented across regions in different years. Curfews lowered spending on private education among rich families, which then reduced education spending by low-income families.

As you can see from this graph, the curfew was exogenous shock, lowering spending.

Poorer families can’t afford to spend as much on education, so they have fewer children

Kim and colleagues reason that poorer families spend a larger share of their income on education in order to catch up with the rich. This lowers fertility.

Can status competition be reduced with taxation?

Kim and colleagues argue that taxing spending on education will lower investment and enable the poorest to catch up with the rich and have two children. In their model, a 22% tax on education spending would reduce spending by 39%.

This model assumes that the main driver of change is ‘status externalities’. When this externality is removed, poorer people are more likely to have children. This is because it is now less costly to keep up with richer parents.

But looking at the underlying calculations (the reduced form estimates of spillovers), I’m not sure the effects are so large? According Kim et al, low-incomes families typically spend 6% on private education. Even if the richest 15% reduce their education spending by 10%, this only reduces education spending among the bottom 50% by 0.5 percentage points. That seems relatively small?

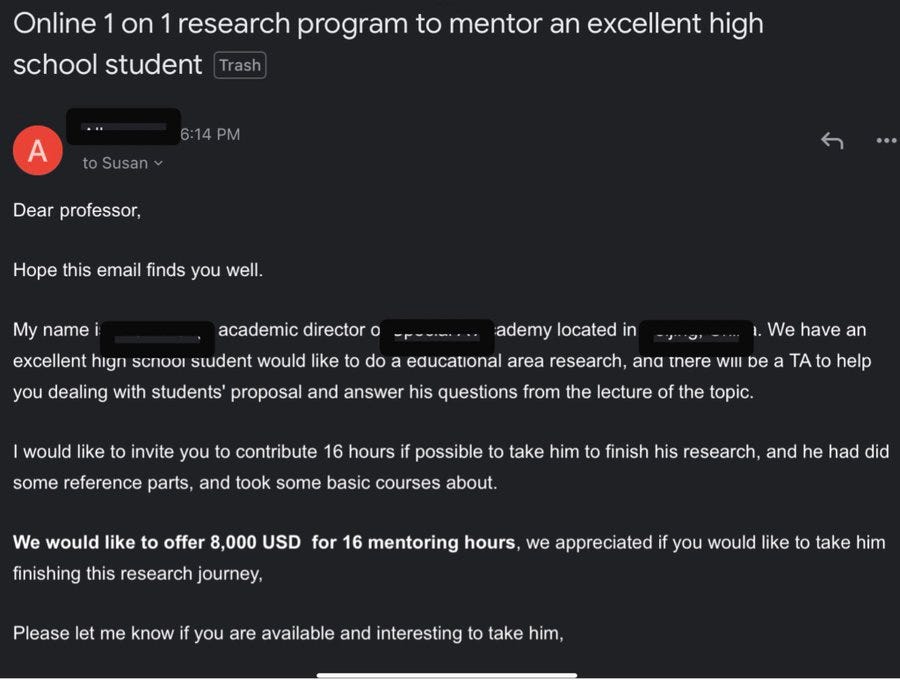

Moreover, is it really possible to significantly suppress rich parents’ investment?

Wealthy families - wanting the very best - may simply spend even more. Susan Dynarski (Professor of Economics at Harvard) recently shared an email, offering USD $8000 for 16 hours of mentoring a high school student. 😲😲😲😲

Parental love is limitless!

This trend is global. As inequality rises, competition drives up ‘intensive parenting’.

East Asian societies are ultra competitive. As Ms Park explained to the Straits Times,

“Some families even move to Daechi-dong [home to thousands of educational academies] only for educational purposes – that’s how obsessed mums are”.

Ms Park actually quit her executive job due to ‘working-mum guilt’, wanting to properly support her daughter’s education. Ms Kim Eun-hye expressed similar concerns:

“I think the education craze stems from wanting my kids to be successful. Letting go of that desire isn’t easy because I’m afraid my kids will be left out in Daechi-dong’s competitive society” .

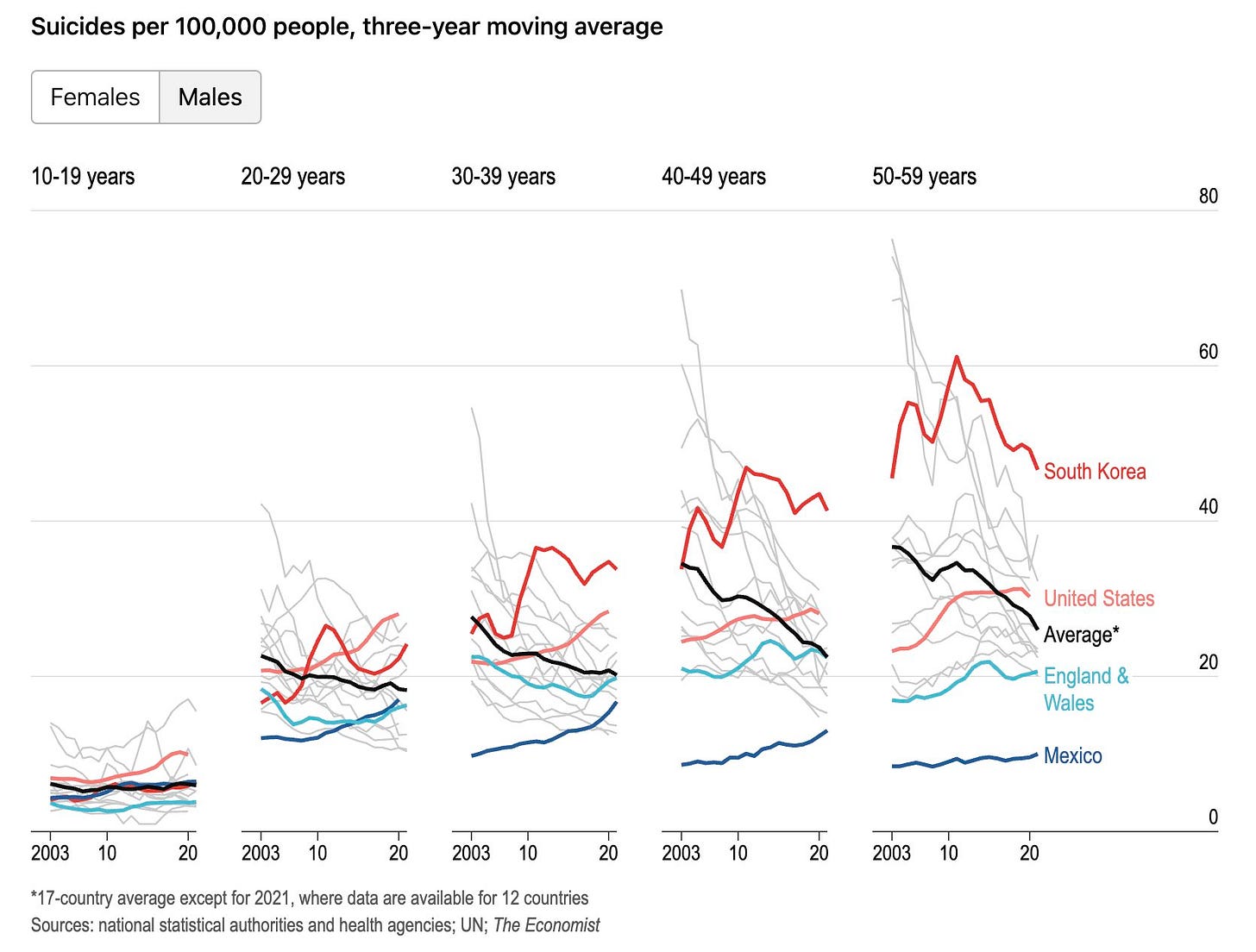

Korean men who lag behind are more likely to contemplate suicide. Status competition may help explain South Korea’s extremely high rate of suicide.

For the past fortnight, I’ve been staying in at a university campus in Hong Kong. Everyone is aiming for the top. Sons are under massive pressure to succeed. Given this culture, I doubt a 22% tax is enough.

In China, private education has been entirely banned, but there’s nevertheless been a rise in underground private tuition and online learning. Illicit tutoring classes are disguised as ‘housekeeping’. The Straits Times quotes Ms Cathy Zhu (in Shanghai) who said her son’s mathematics tutoring classes have become doubly expensive.

“As long as the high school and college entrance system still exists, there is absolutely no way to achieve such ‘reductions” .

The educational arms race is real. The unresolved question is how to address it.

Special request:

I am heading to South Korea to give a talk at Yonsei University.

South Korea is extremely important for my book, as it presents an unresolved puzzle. It has the largest gender pay gap in the OECD, young men recently voted for an ‘anti-feminist president’, and there’s an emergent feminist movement.

If you are Korean or have contacts in Korea, I would very much appreciate any introductions for interviews. Language is no issue, as I have excellent translation technology. Thank you so much!

Fascinating insight that I hadn't seen up until now, despite reading countless essays on this topic. I live (as a parent of a young child) in Sweden, where private tutoring of this type is almost unheard of. Preschool/daycare here is essentially free. University is famously tuition free (with even living costs subsidized by no-interest loans). And other costs of parenting are subsidized to the level that they're much less salient.

In my own experience, my toddler-age son basically costs me less than owning a Golden Retriever! When my son was born, the birthrate here had for the first time averaged higher than in my native United States, and I could certainly understand why: given how we didn't face thousands in out-of-pocket hospital delivery costs, weren't staring down the barrel at five-figures-worth of annual childcare, and basically didn't even really have to factor finances into this reproductive decision at all. What a relief!

However, *even so,* Swedes are still sensitive enough to economic conditions that the birthrate has fluctuated according to how the economy's going (most recently dipping noticeably this year along with Sweden's poor immediate economic prospects to 1.6/woman). Which suggests to me that either there's some factor that overshadows this "status externality" or else parents are *extremely sensitive* to the modest costs that even highly-subsidized Swedish parents face living in a much more egalitarian society than South Korea's (or the United States').

This result confounds my priors and also, it must be said, undercuts my own policy preferences for fixing this issue in the United States. Because Sweden's family-support is basically as good as it gets. The stuff of the wildest dreams of Progressives in the United States (and even many heterodox Conservatives emulating the example of a Poland or a Hungary with far-right "welfare chauvinism" to support fertility). But if the ho-hum result of all that spending is... 1.6 children per woman, on average, that's a bit underwhelming. This is still one of the highest rates in the EU, but that's more a measure of how arguably catastrophic the demographic collapse on the continent is.

If Korean parents are too obsessed about their children's future social status, one way to discourage that would be to compress the country's income distribution, so it matters less which decile the kids end up in.

And one way to do that would be to pay very generous flat-rate child benefits funded by progressive or even proportional taxation... which is also the most straightforward way to incentivize fertility directly.

Wouldn't that likely be more effective than taxing or outlawing private tutoring?