Male Violence and the Myth of Female Freedom

In the wake of the sexual revolution, Western feminist scholars sought to show that patriarchy was not inevitable. They scoured archives and ethnographies for evidence that women had not always been confined, silenced or powerless. Across continents, they highlighted powerful queen mothers, spirit mediums, long-distance traders, cunning concubines and covert resistance.

Rejecting assumptions of universal male dominance, academics began asking when, where and why women became oppressed. Explanations ranged from plough-cultivation and patrilineal clans to private property, state-development and colonialism. Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia’s small-scale matrilineal and bilateral societies were often presented as counter-examples - where women inherited land, lived near kin, ran markets, and exercised spiritual authority. ‘Warrior women’ of the Eurasian steppe are likewise esteemed for their military prowess.

But have these celebrations of female freedoms omitted a major constraint: extreme violence? By reading a wealth of historical ethnographies and analysing the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (a comparative dataset of pre-industrial societies), I have discovered that many cultures renowned for female prominence also experienced pervasive homicide, assault and warfare. Organised male coalitions amassed power through slave-raiding and labour coercion, sustaining ecologies of fear.

Inter-disciplinary Consensus

Across economics, anthropology and evolutionary theory, I notice a common assumption: where women inherit land, choose partners and move freely, the society is seen as more gender equal.

In A Natural History of Patriarchy, David-Barrett suggests that our ancestors once lived ‘gender harmony’, and draws on contemporary hunter-gatherers as exemplars of equality. Female dependence on male providers, he speculates, only arose with the transition to agriculture, which raised fertility while exacerbating food insecurity.

Graeber and Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything similarly emphasise autonomy in pre-state societies. Drawing on Jesuit accounts of Wendat and Montagnais–Naskapi, they describe women as having “full control over their own bodies, and that therefore unmarried women had sexual liberty and married women could divorce at will”. Nuer women in the Horn of Africa are likewise portrayed as exercising freedom over their sexuality and reproduction.

Economists Sarah Carmichael and Auke Rijpma construct a composite index of “Family Constraints on Women’s Agency”, drawing on ethnographies recorded between 1860 and 1950 from nearly two hundred societies. They combine patriliny, patrilocality, polygamy, cousin marriage, marriage payments, inheritance, extended households and clan structures. Their framework implies that when women are free from patrilineal control, they exercise greater autonomy.

These accounts all assume that where women inherit property, choose partners and move freely, the society was relatively gender equal. Perhaps the past was not so bad?

Violence

Even if a woman is not subordinated to lineage elders, she may still be vulnerable to violent predation. Sexual permissiveness does not mean genuine choice if she can be abducted, enslaved and raped. When men can get what they want via coercion, they need not charm women with displays of devotion or companionship. Brute force wins.

Even if women can choose their husbands, in dangerous places they may strategically partner with aggressive men who can provide protection. Conflict societies also tend to glorify male aggression, raising boys to be tough, show readiness to retaliate, and intimidate potential foes. Male coalitions gain power through organised violence, then consolidate dominance through spectacular punishment.

Once we recognise how violence shapes culture, we may wish to revisit rosy narratives. Take pre-colonial Southeast Asia. “Men of prowess” gained power by militarism and labour coercion, while men could sell wives and children into debt-bondage. “Virtually every large trader was, simultaneously, a slave-raider. Every military campaign, every punitive expedition was a campaign for captives who could be bought, sold, or held”, writes James Scott.

In peripheral small-scale societies of Southeast Asia, Barbara Andaya details how young men went on head-hunting expeditions to mark their passage to adulthood, while young women celebrated men’s violence. In 1679, Governor Padtbrugge observed that men’s tattoos tracked the number of men they had killed, which their wife copied in pride. An 18th century Malay manuscript records young Abung women rejoicing at raiders’ return.

Northern Thai villagers recall that girls could be captured as “play wives” by passing militia, and folklore tells of village parents hiding daughters by smearing their faces with fish paste. In Palembang and Jambi, east Sumatra, rulers raided local stores of pepper and carried off their “prettiest daughters”.

Reflecting on this evidence, I began to suspect that cross-cultural research has radically understated historical patriarchy by ignoring pervasive violence.

Does ‘Female Agency’ track Safety?

Curious, I turned to the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (SCCS) - a widely used anthropological dataset of 186 small-scale societies. Each society is coded on variables such as descent, marriage, gender norms, political organisation, homicide and warfare. This sample was designed to minimise regional clustering and shared historical ancestry, thereby strengthening cross-cultural comparisons.

Like all such datasets, this coding relies on observations recorded at particular time periods and reduces social complexity to discrete categories. It cannot capture internal variation (for example, elites versus marginalised sub-groups) nor long-term change. Nevertheless, it provides the most systematically comparative evidence currently available. Separate research teams coded different measures of violence, thereby reducing the risk that any single interpretive bias might drive the results.

Below, I explore whether conventional indicators of female freedom correlate with violence.

1) Violence was pervasive

In 80% of coded societies, male toughness was explicitly glorified.

In 80% of coded societies, wife beating was reported as common.

Institutional rape was present in 53% of the societies coded on that variable. Rape, or gang rape, was a socially legitimate tool of punishment, discipline, or warfare.

The Montagnais–Naskapi - caribou-hunting people of northeastern Canada described by Graeber and Wengrow as respecting female liberty - are coded as practising institutional rape.

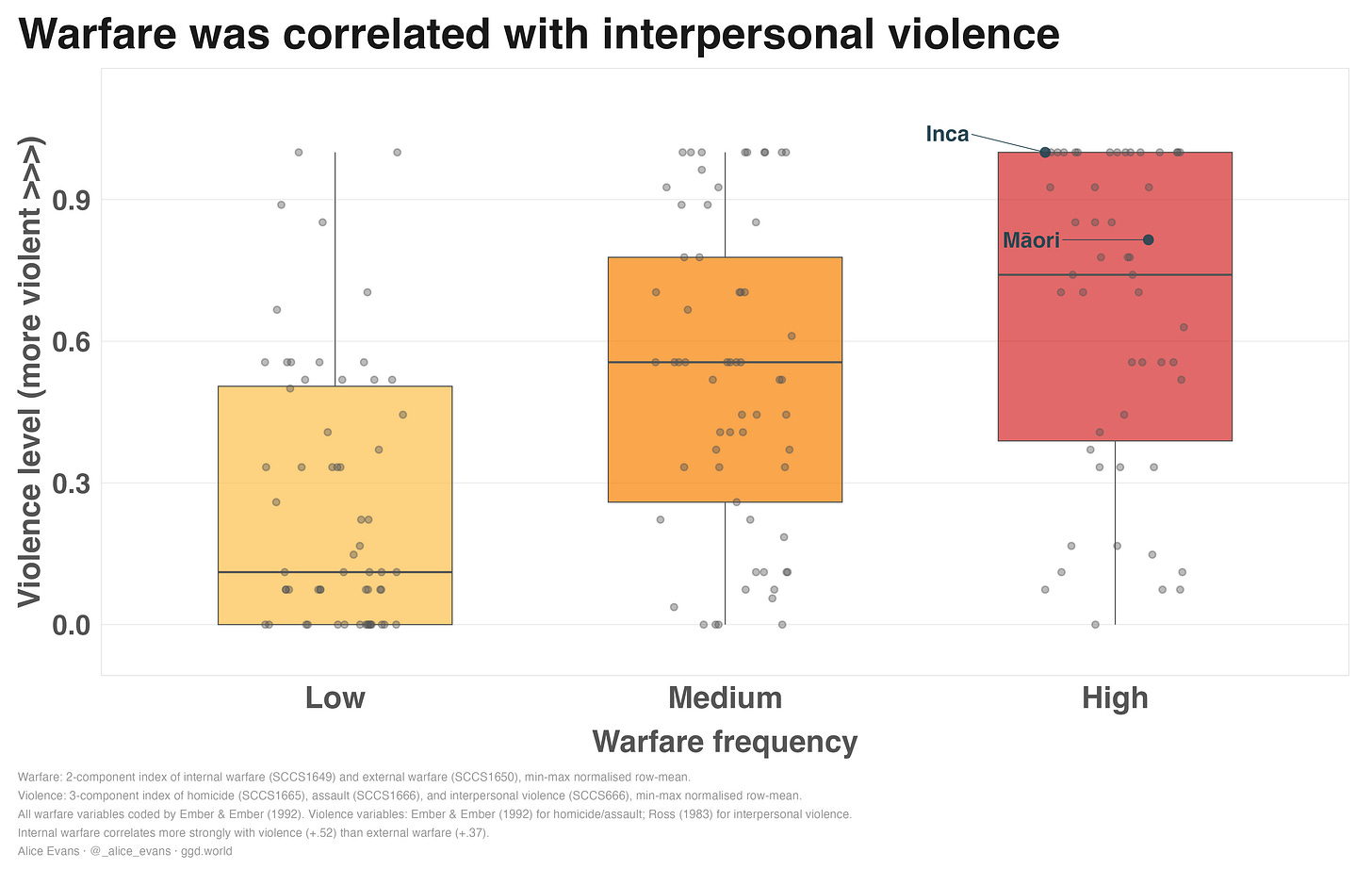

2) Warfare is correlated with interpersonal violence

Not all pre-industrial societies were violent or warlike. But societies that frequently waged war also tended to exhibit more interpersonal violence - more assaults, coercion and homicides.

Ember and Ember (1994) suggest this pattern could be partly driven by warring societies socialising boys for aggression. Similarly, I find that societies with high homicides and assault tended to glorify toughness.

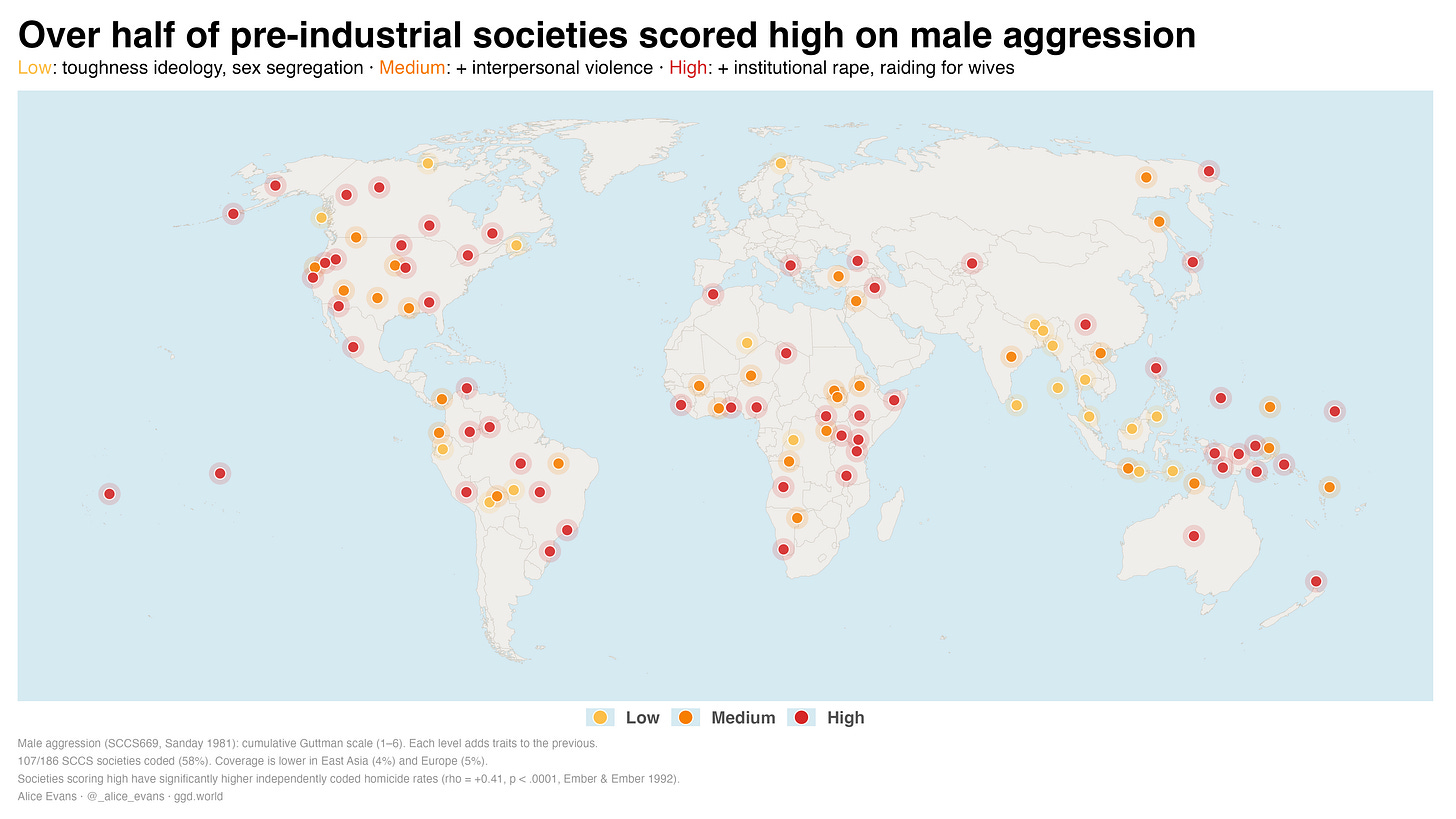

3) Over half of pre-industrial societies score highly on male aggression

Male aggression is coded on a cumulative Guttman scale, with the highest score assigned to societies that institutionalised rape and raided for wives. Over half of pre-industrial societies in the SCCS reach this maximum level.

The Yanomami, Chuckchi, Kazakh and Somali all score high on male aggression, warfare, interpersonal violence, glorified toughness and institutional rape. In the absence of a centralised monopoly of force or reliable guarantee of security, Somali patrilineal clans defended pastoral herds and lineage honour through threats of retaliation and feud.

Only 19% of coded societies did not glorify toughness. These were typically more peaceful, eeking out livelihoods in peripheral forests and rugged uplands - like India’s Garo and Adivasis.

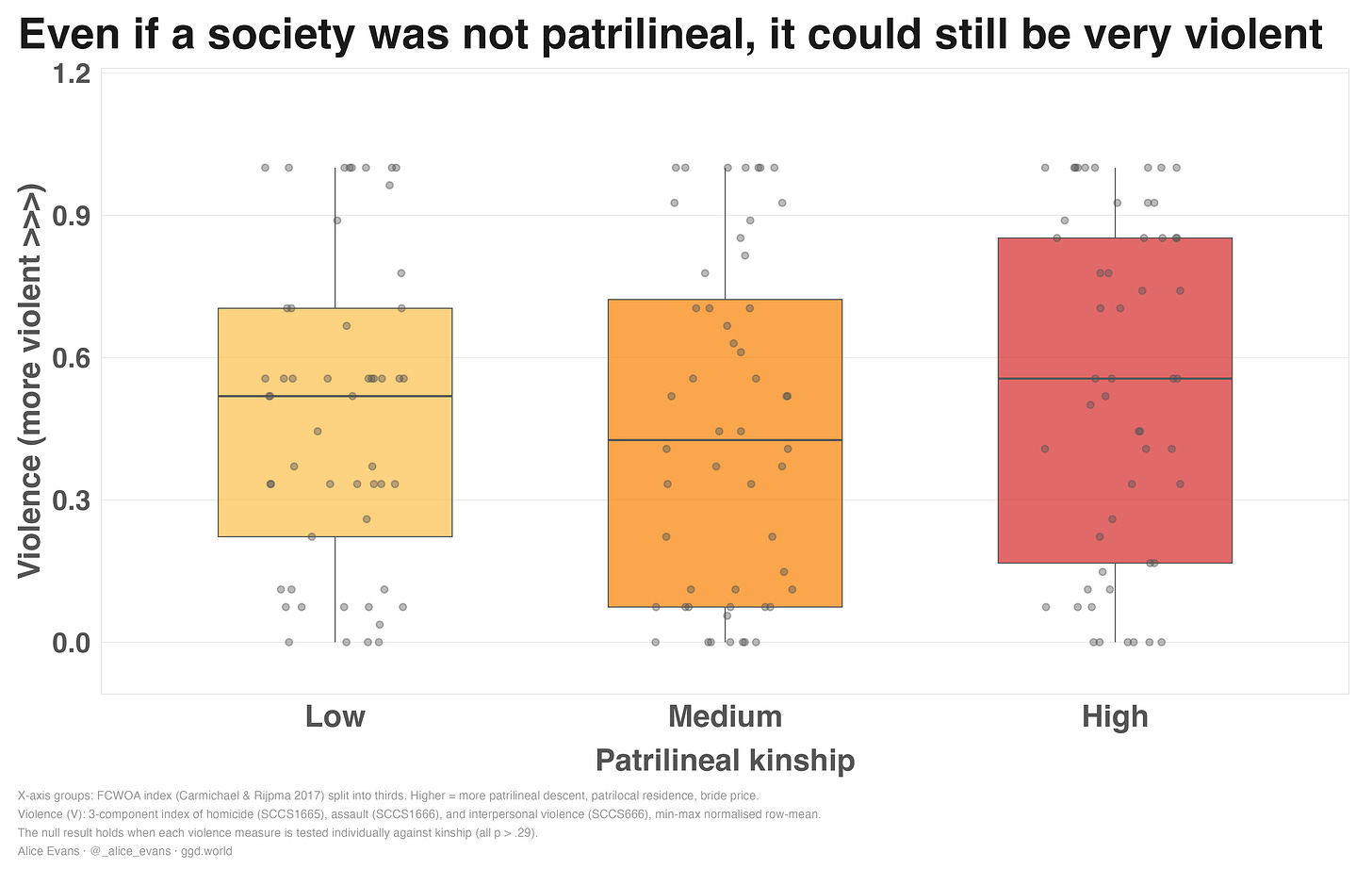

4) Conventional indicators of female agency are statistically unrelated to violence

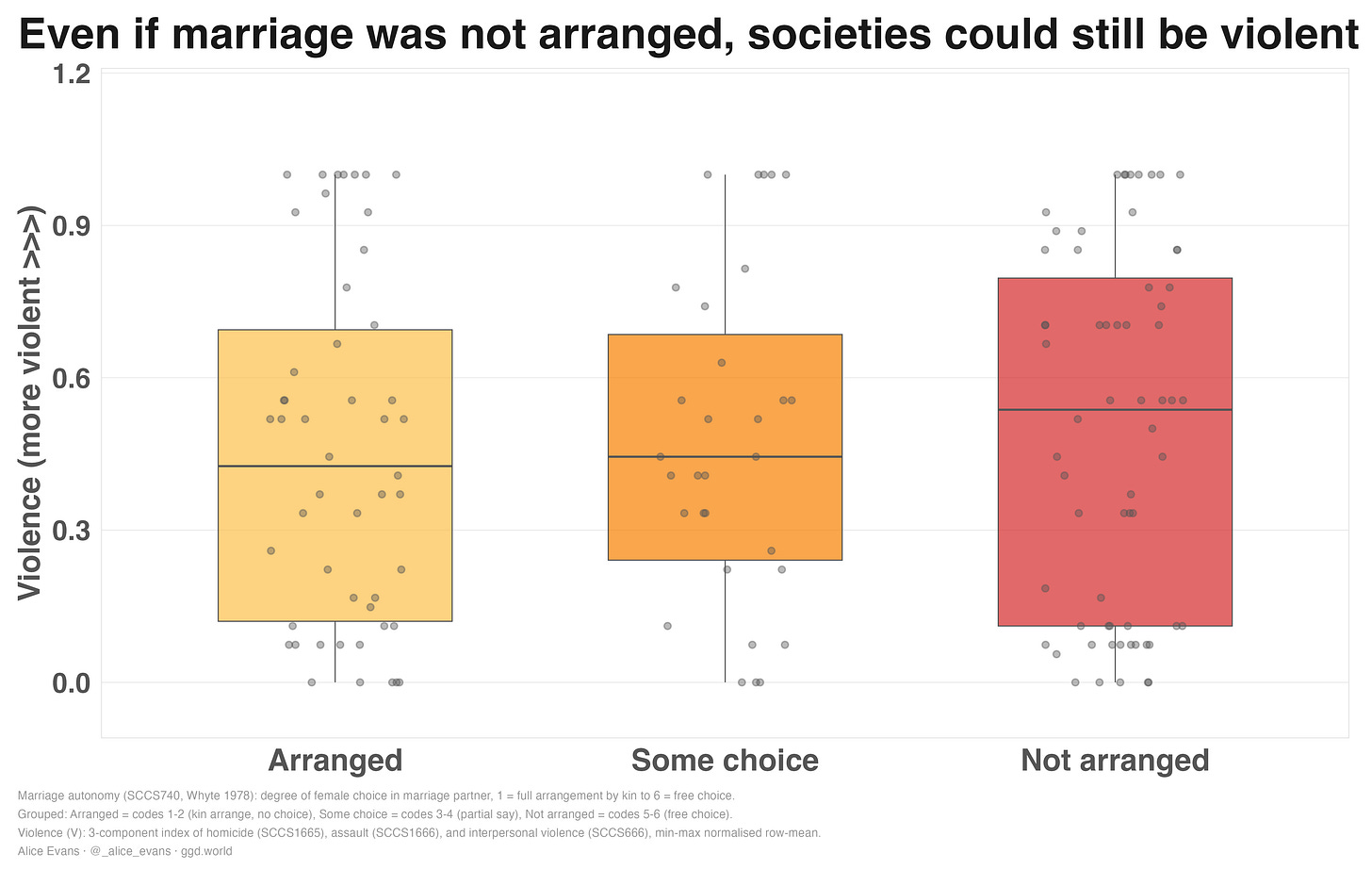

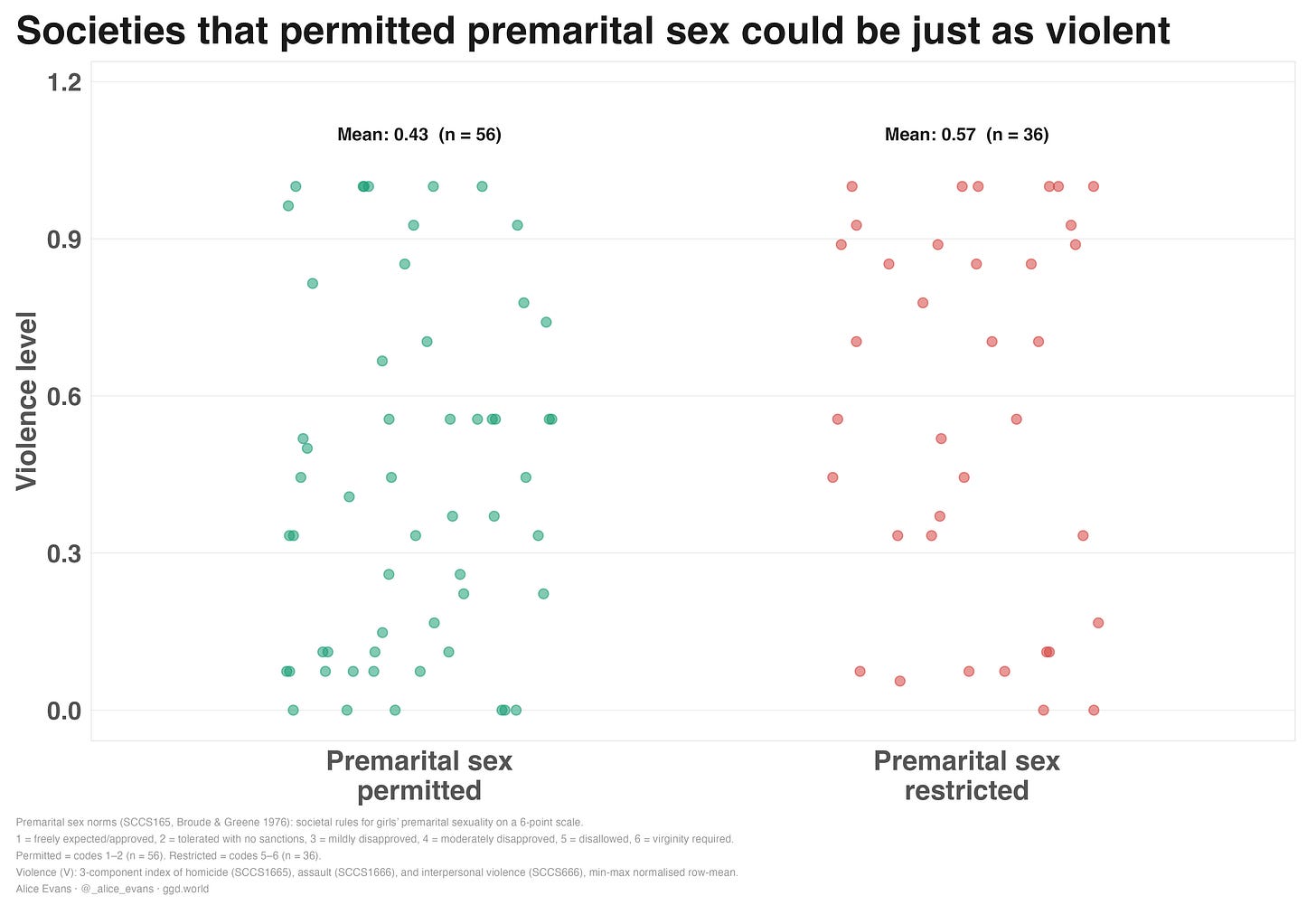

Standard measures of ‘female agency’ (including patrilineal descent, patrilocal residence, restrictive pre-marital sex norms, and arranged marriage) are statistically unrelated to measures of violence.

The graph below plots the Carmichael–Rijpma ‘Family Constraints on Women’s Agency’ index against violence. Two components account for most of the variation: patrilineal descent and patrilocal residence.

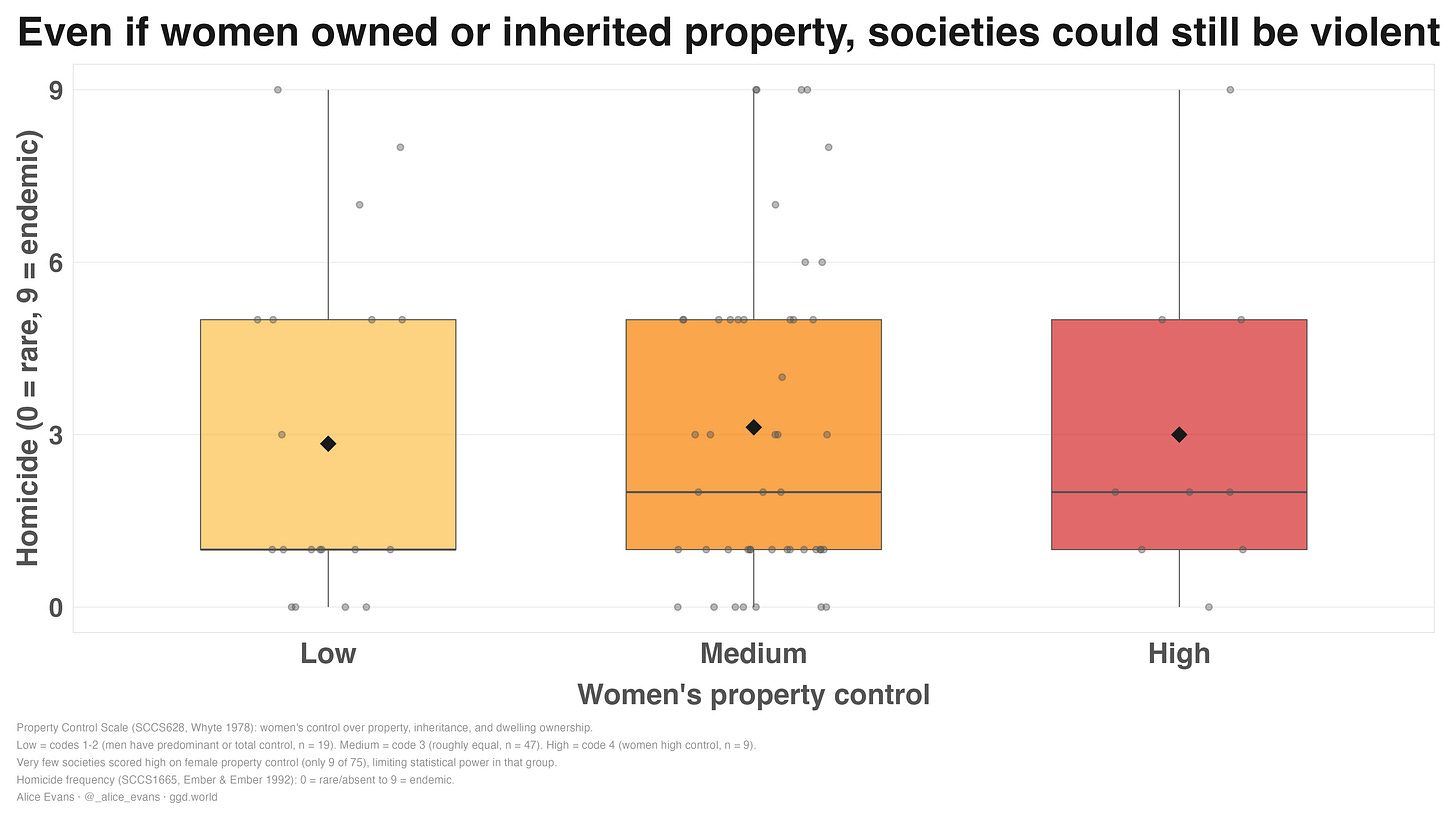

I also plot female property ownership against violence. As you see, there is no relationship. Even if women lived near their natal kin, owned property, or were free from arranged marriage, they might still be vulnerable to male predation.

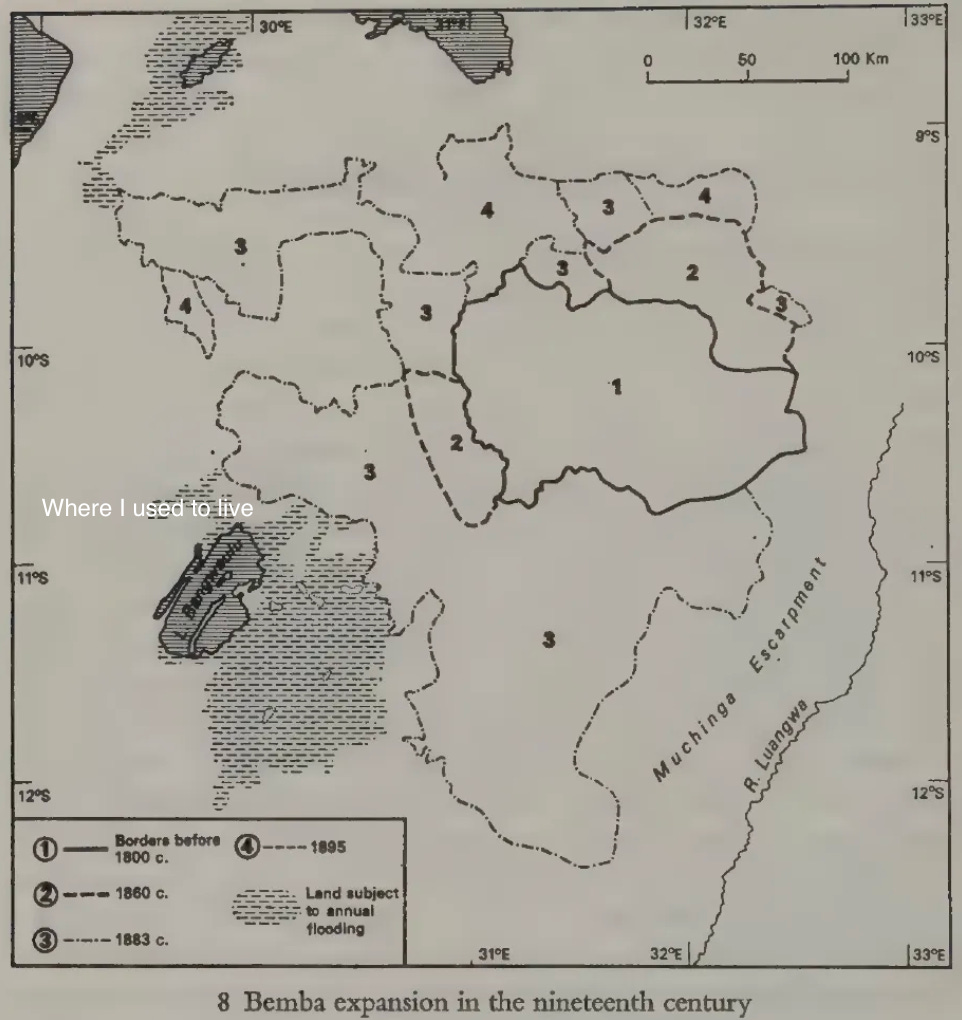

The Bemba in Southern Africa were shifting cultivators, valuing not property but ‘wealth in people’. They practised matrilineal descent and matrilocality. A groom typically performed several years of labour for his in-laws to demonstrate readiness for marriage and then lived nearby. Women could divorce and return to their natal kin, often remarrying.

In the 19th century, this co-existed with warfare: Bemba chiefs expanded their territory by raiding neighbouring groups and taking captives. In 1832, Gamitto reported that ‘the Bemba.. are today powerful and feared by all for their fierceness’. In 1895, [Chief] ‘Ponde’s men captured Chitimbwa’s village, killed the chief and carried away rich spoils of cloth, salt and women’.

In the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, wife-beating is coded as common. Still today, in Luapula (the Bemba-heartland, where I used to live), over half of women say that wife beating can be justified.

The Igbo of southeastern Nigeria are often presented as evidence of a more egalitarian precolonial order. The language is largely gender neutral, political authority was decentralised and women organised powerful assemblies. In village-wide gatherings (mikiri), women shared grievances, regulated markets and coordinated sanctions. If a man abused his wife or violated market rules, women might gather at his compound, bang pestles against his walls, shame him publicly, and create a din until he submitted. This was called ‘sitting on a man’. During the Women’s War of 1929, the same networks mobilised against Warrant Chiefs (colonial appointees).

British colonial officers and missionaries can be rightly faulted for neglecting these significant institutions. Yet later correctives seem to have ignored the wider context. In the SCCS, the Igbo rank among the highest for homicides, with frequent inter-village warfare and retaliatory violence.

The Fon of Dahomey are coded with the maximum score for female power. By the 1840s, they had 6,000 female professional soldiers - recently popularised in the Hollywood film, “Woman King”. Women ran markets and the Queen Mother (Kpojito) was politically influential.

Yet the Dahomey also had interpersonal violence, institutional rape and wife-beating. This was a slave-raiding state, which gained strength from organised warfare. Elite female prominence co-existed with slave-raiding, coercion and enslavement.

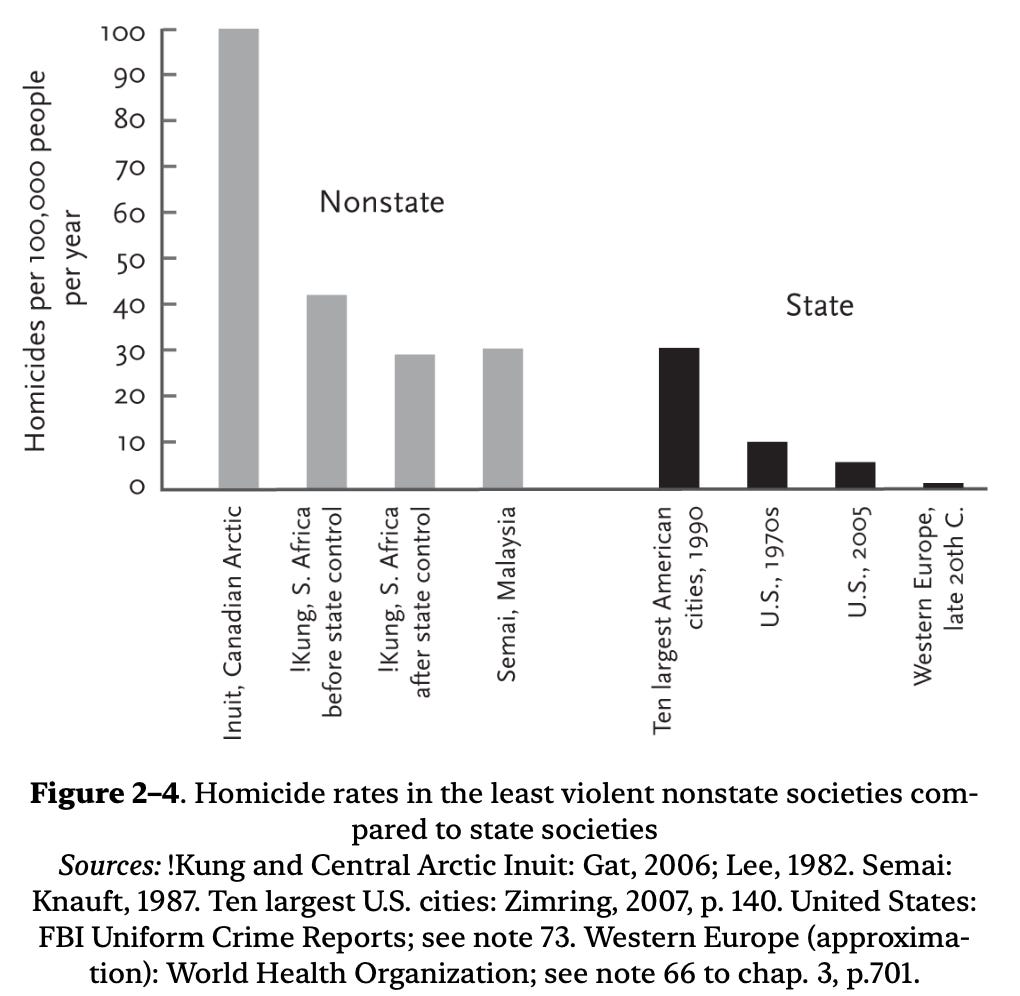

Vast populations lived under insecurity and retaliatory violence. It follows that regimes which successfully monopolised force and pacified society, thereby reducing the returns to male aggression, created a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for greater gender equality

Violence Entrenches Patriarchy

Male violence isn’t just downplayed in the historical record, it’s often omitted from discussions about contemporary societies. For example, the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report tracks health, education, employment and political representation. All four are important, but omit a hugely important obstacle emphasised in so many of my interviews across the world: male aggression, coercion and brutality.

Economists may suggest that property ownership raises women’s bargaining power, but this surely breaks down if one can be captured and enslaved. Likewise, sexual permissiveness does not mean female agency when women may be abducted by male predators.

“In the 1990s, Russia was like a Wild West, many of my friends’ dads were killed by the mafia” - shared Julia from Vladivostok. In the shadow of organised crime, working class men learnt to project brutal dominance, uploading videos of their fights, impressing peers with physical aggression. Desperate for security, Russians favoured tough male leaders. Worldwide, militarism and geopolitical threats consistently boost demand for macho leaders.

Today, in Russia-occupied areas of Ukraine, there are reports of killings, abduction, torture, electric shocks, and gang rape. Victims of sexual abuse range in age from four to 82. This reflects a recurring pattern of sexual violence as a weapon of war.

Over in Latin America, 52-58% of people say they live in the presence of criminal groups, while 12–16% report some form of criminal governance. Across the continent, high homicides strongly predict high femicides. Across Mexico, Costa Rica and Brazil, women often described older men as being intensely ‘machista’ - controlling and quick to anger. Some interviewees attributed their self-doubt and nervousness to early experiences of fear and intimidation.

Amid climate stress and state fragility, the African Sahel has seen a surge in Islamist militancy and armed conflict. The region now accounts for 51% of global terrorism-related deaths.

Protection from Male Predators

In their eagerness to challenge myths of universal male dominance, scholars scoured historical records for evidence of women’s prominence. But across 186 pre-industrial societies, I find that standard indicators of female agency (like matriliny, sexual permissiveness and female political participation) can co-exist alongside homicides, warfare, and institutional rape. Although scholars were right to highlight women’s political participation, this obscures a much harsher reality.

Violence was endemic across many non-state societies. Celebratory narratives of ‘kick-ass’ women often obscure head-hunting, slave-raiding and intimidation.

Going forwards, I suggest that measures of gender equality should incorporate indicators of generalised violence, as a major threat and brutalising force.

‘Getting to Denmark’ doesn’t simply mean gender quotas for political elites, but building states that enforce rule of law and protect vulnerable girls from predators. I would love to see more research on how this can be achieved, worldwide.

Related Essays

Notes

This is a nice example of a useful null finding. These are under-reported in academia, as shown in a new paper by Ryan Briggs.

Male toughness and institutional rape are coded on a cumulative Guttman scale. On this metric, you can have societies glorifying toughness without institutionalising rape, but societies institutionalising rape will glorify toughness. Since this creates a mechanical correlation between these two variables, I also incorporate other, independently coded indicators of violence, such as homicide and assault.

My violence index is a min–max normalized row mean of three standard indicators: homicide, assault, and interpersonal violence. All substantive conclusions are identical when I expand the index to include wife beating and institutional rape, and when I restrict the three-item index to societies with at least two coded components. I also replicate the null results using homicide and assault separately, confirming that the results are not driven by index composition.

I do find a correlation between restrictive premarital sex norms and homicide, but this relationship is driven by 21 societies that are both extremely restrictive and extremely violent. If these cases are removed, the correlation disappears. Looking more closely, this cluster of societies tend to be pastoral economies with organised violence, waging wars for resources, and socialising boys to be aggressive. Otherwise, there is no relationship between pre-marital sex norms and violence.

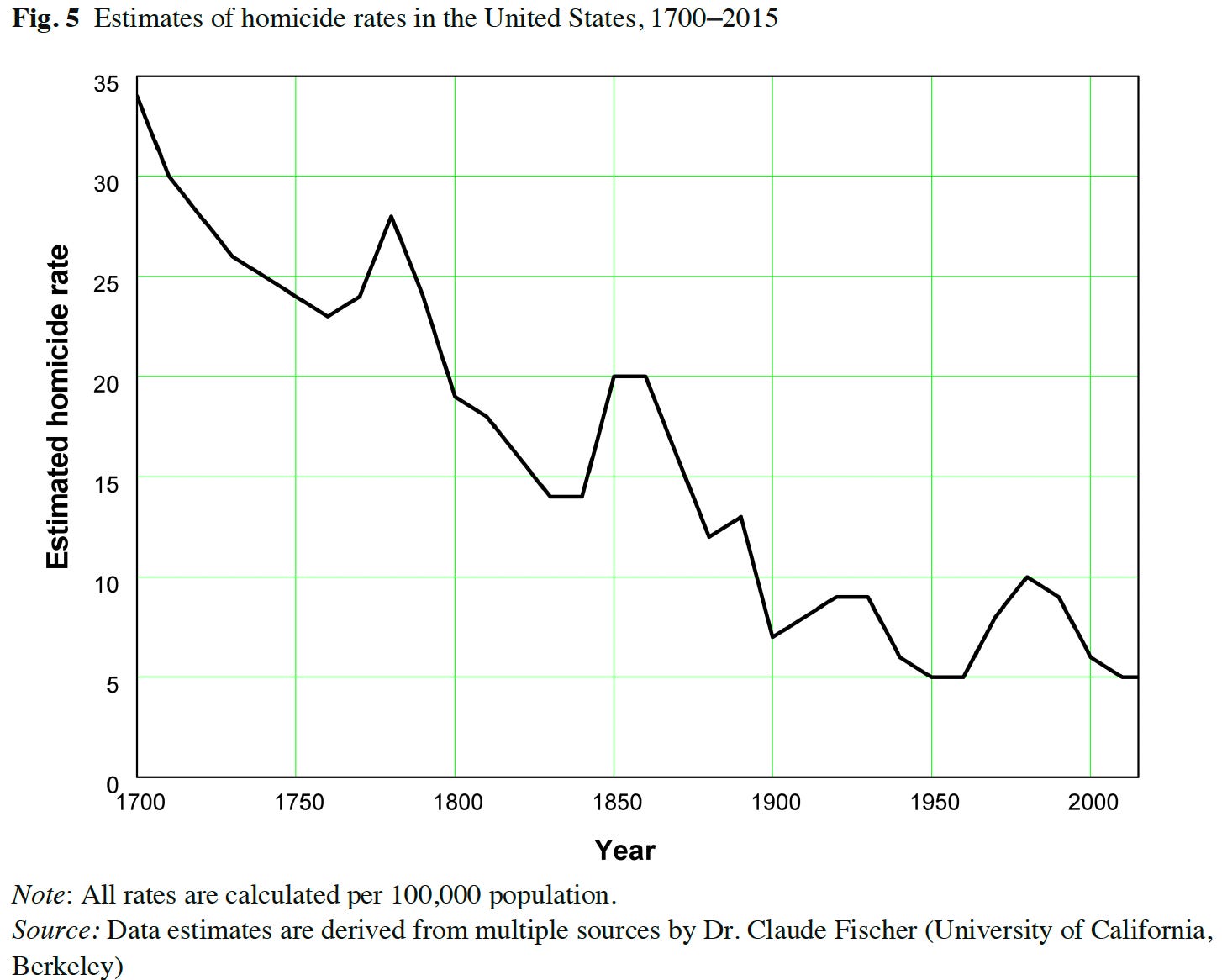

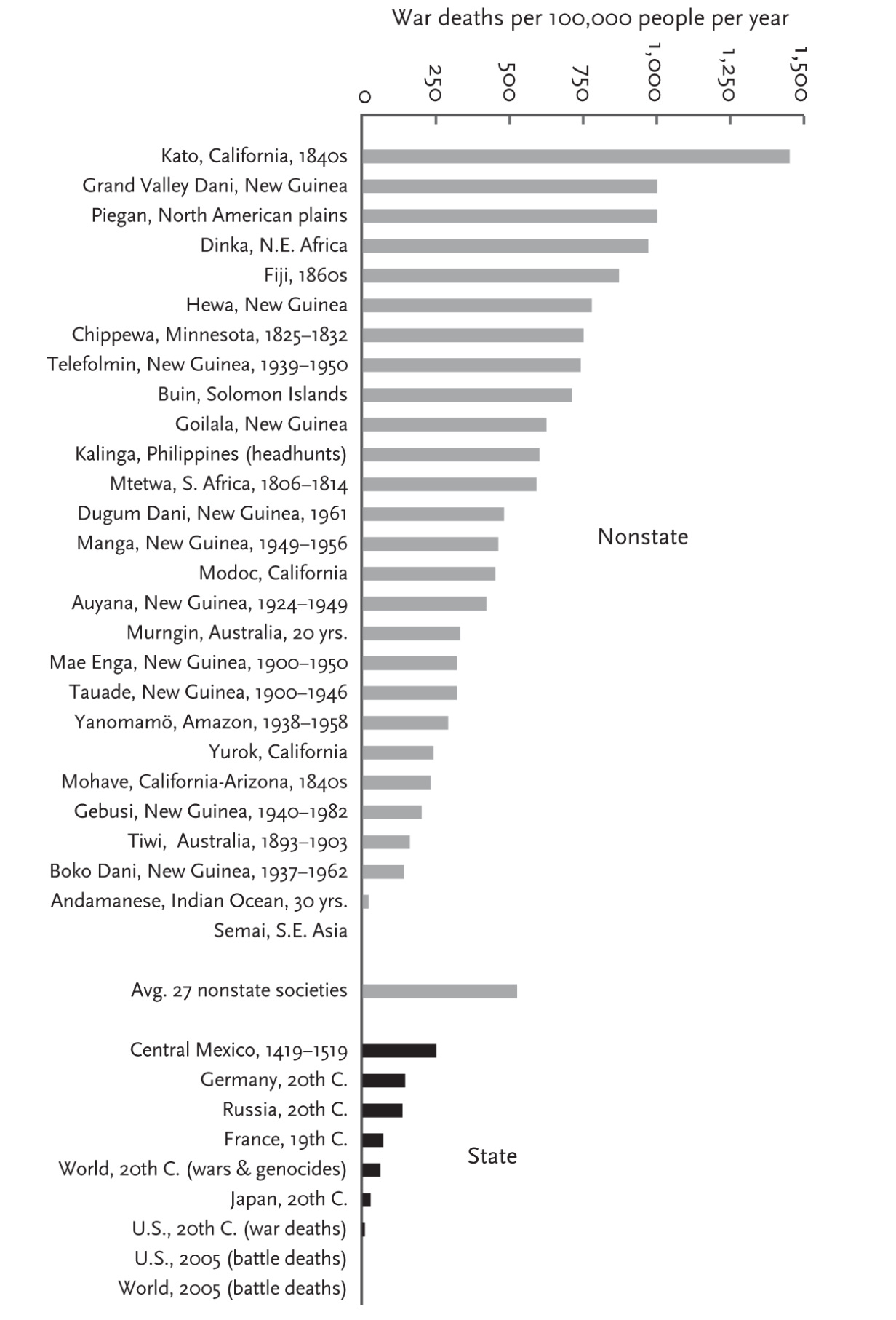

In “Better Angels of Our Nature”, Stephen Pinker suggests that small-scale societies had extremely high rates of war deaths and homicides.

There's this frustrating tendency of humanities academia to put premodern and modern hunter gatherer societies on this pedestal of having the answer to everything, and gender equality is very much one of those things.

Excellent article. But nobody should ever underestimate the dominant power of physical force (including both capacity for superior fighting capacity and work). Ultimately, in the struggle for survival, including procreation, physical force was always the trump card. Most women and the majority of men and almost all children were on the receiving end. Power was not rooted in sex/gender, but base biological capacity for force. The failure to appreciate this in feminist thinking is why feminism, by definition, is limited as a vehicle for understanding humanity. Women need to see themselves as smaller, less biologically forceful people.