Wartime Patriarchs

When states are under siege, they militarise. Frightened publics want bellicose leaders and higher military spending. Once in power, militarists entrench their institutional and cultural dominance. They fan fears, act tough, and secure public support.

Conflicts change popular priorities, not least by reinforcing respect and reverence for macho leaders. Countries threatened by war and terrorism are thus more likely to be governed by men. Peace, therefore, is a hugely important pathway to gender equality.

In this piece, I draw on the latest academic research showing that:

Terror instills a preference for tough leaders;

Men are stereotyped as superior military strategists;

Terrorism only benefits male (not female) executives;

Countries under attack prefer and elect more male leaders;

Existential threats may help explain persistently patriarchal governance in Russia and the US.

International security is thus an important precursor to female leadership.

Terror instills a preference for tough leaders

Existential threats trigger anxiety, motivating the cultural adaptation of tightness. Fearful people want their group to be strong and united in solidarity. They rally in support of authoritarian leaders and strictly punish norm violators.

After European terrorist attacks, German Twitter users adopted the language of the far-right. They increasingly tweeted about immigrants and Muslims. This shift in language is associated with more votes for the right right.

Even though 75% of terrorist attacks are by right-wing nationalists, exposed Germans (especially those who are less educated and politically active) nevertheless become more likely to vote for the far-right. Bomb attacks create an exogenous shift in culture.

Now, what kind of leaders are seen as ‘tough’?

Men are stereotyped as superior military strategists

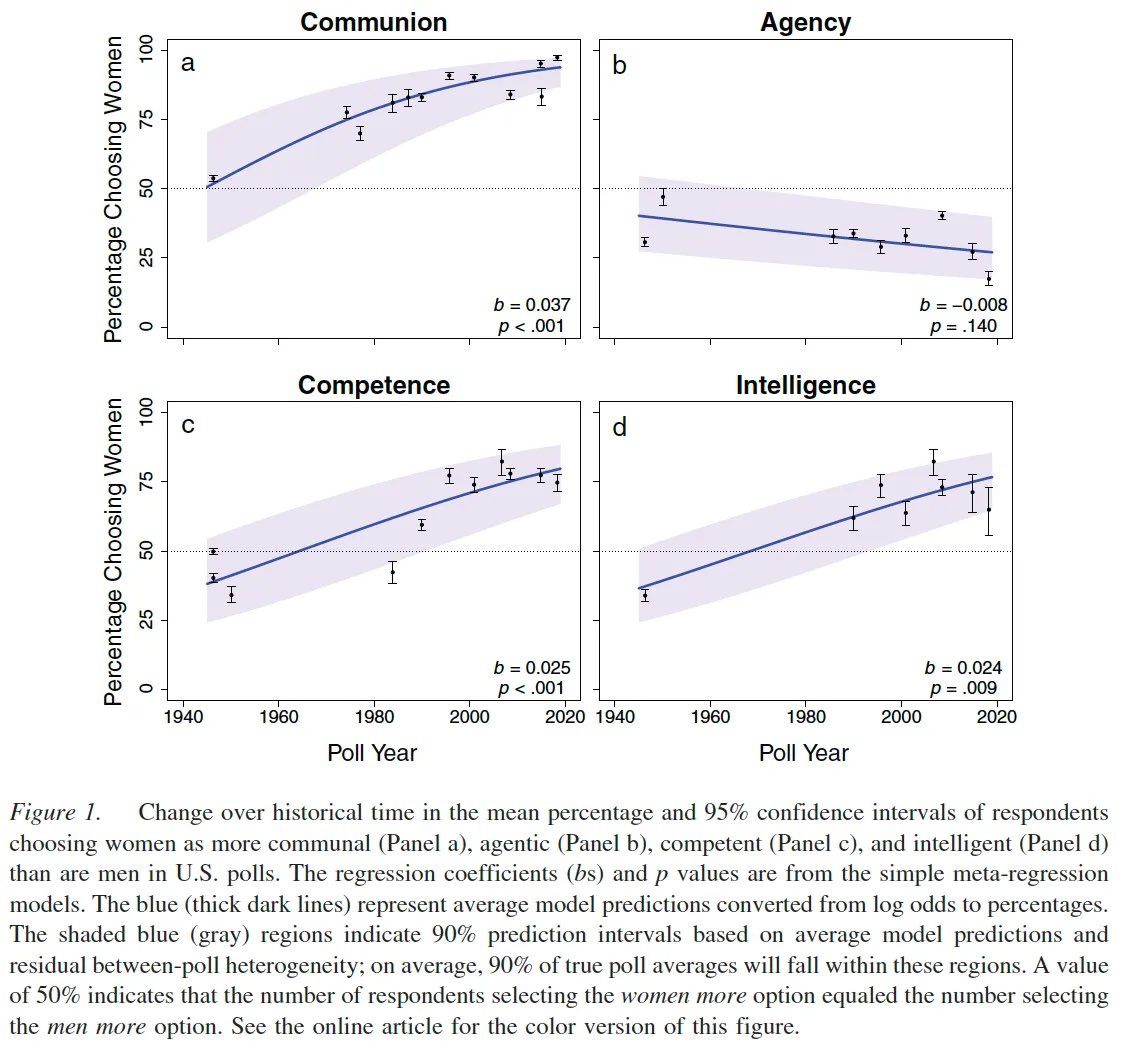

Over the past 60 years, the West has experienced soaring female employment, sustained feminist activism and a massive shift in stereotypes. But although American women are increasingly seen as equally competent and intelligent, they are still presumed to be less agentic and assertive. Men are regarded as more forthright and dominant.

The persistence of gender stereotypes has important implications for politics. Female leaders are recognised as equally competent when it comes to deficit reduction, corporate crime and poverty. They are actually seen as more capable of addressing child welfare. Across a range of issues, Americans do not discriminate.

However, Americans do view men as better military strategists. ‘Hawks’ - who prioritise geopolitical security - express a particular preference for strong, authoritarian, macho leaders.

Terrorism only benefits male executives

Terrorist attacks usually cause people to become more patriotic and rally around their leaders. Does this hold for both men and women?

Holman and colleagues build a pooled dataset for 66 countries, spanning 1975 to 2017, comprising international terrorist attacks and quarterly data on executive approval. They find that international terrorist attacks only boost support for male incumbents.

Let me illustrate this pattern with case studies of the UK and the Philippines.

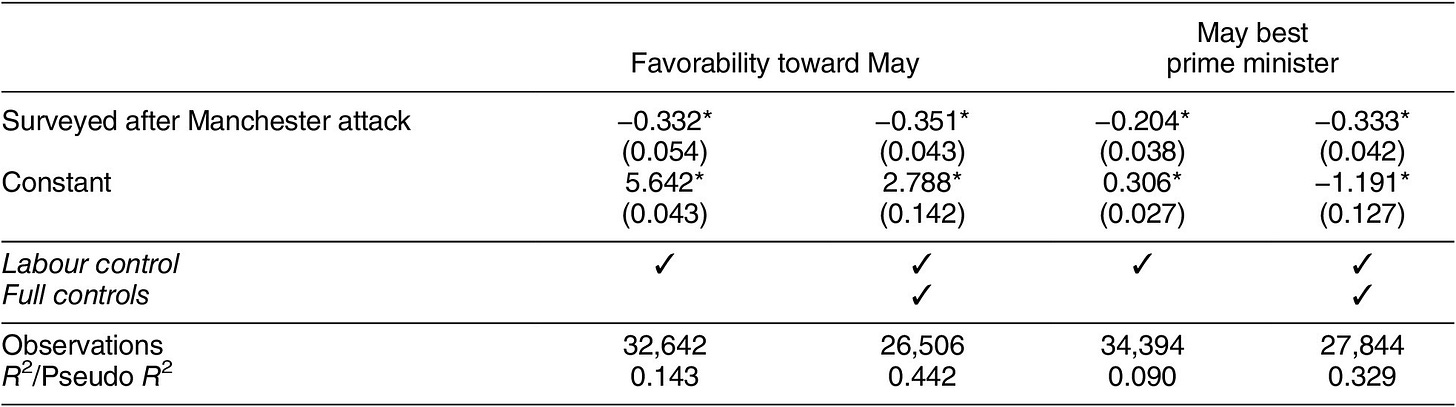

An Islamic extremist bombed Manchester Arena in 2017. 22 people were killed, over a thousand were injured. Theresa May was the UK prime minister, leading a right-wing party, with prior personal responsibility for security.

To investigate possible impacts on May’s ratings, Mirya Holman, Jennifer Merolla and Elizabeth Zechmeister cleverly tap into an ongoing YouGov survey. This public opinion poll coincided with the attack: half the respondents were surveyed before the attack, half after.

After the attack, May suffered a sharp decline in popularity, especially among Brits who were more sexist, and/ or lived near the attack.

The Philippines has endured sustained terrorist attacks - from both leftist insurgents and Islamic militants. Ryan Carlin and colleagues suggest that terror has only corroded support for the female president.

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (2001-2010) actually presided over fewer attacks than her male successor Benigno Aquino III (2010-2016). But her approval rating was far lower (23% vs 55%).

When terrorist attacks soared in 2008, Gloria Arroyo’s approval rating halved (to 12%). Attacks also doubled under Benigno Aquino III, but public approval rose (to 64%). Filipinos rallied in support.

Countries under attack prefer and elect male leaders

In countries with more hostile security environments, people tend to prioritise national defence. This same group tends to prefer male leaders. In countries with larger militaries and conscription, people are even more biased.

Nam Kyu Kim and Alice Kang show this by combining country-level security threats and World Values Surveys for 84 countries. External threats remain positively and statistically significant even when controlling for GDP per capita, democracy, Islam, female employment, and female legislative representation.

Alice Kang and Nam Kyu Kim also find that countries facing external territorial threats have more men in legislatures. This is associated with military size, military spending and military conscription. The cult of war turbo-charges patriarchy.

Is this just an effect of authoritarianism?

Autocrats are much more likely to wage war - argues Chris Blattman. Absent public accountability, they can sacrifice bodies with impunity. Russia’s imperial and contemporary rulers have tended to use men as cannon fodder, conscripting their services for geopolitical expansion. Autocrats also repress feminist mobilisation, which has been a major impetus for female representation. So the correlation between war and patriarchal leadership could be entirely spurious.

I think that’s is possible, but inconsistent with the available evidence.

Even in relatively gender equal countries like the US, men are still stereotyped as superior military strategists, and preferred by those who prioritise security.

Terrorism studies are also valuable, since this is an exogenous shock. As we have already seen, this triggers a lurch to the right and loss of support for women.

Kang and Kim incorporate both objective indicators of territorial threats and also public concern for defence. People who prioritise defence want to be led by men.

Kang and Kim also control for democracy. Another useful paper is by Theresa Shroeder, her sample only includes democracies.

In democracies, conflict increases male representation

When democratic states face external threats, they tend to increase military spending, heighten aggression and elect more men.

Harnessing a dataset of democracies (from 1981 to 2007), Theresa Shroeder finds that states involved in more rivalries have more male leaders. The legislature of a state with no rivalries is usually 81% male. Those with two rivalries are 94% male.

My only reservation is that this omits domestic terrorism, so I’d actually anticipate the effects of conflict to be larger.

Conflicts compound “The Great Gender Divergence”

If militarism strengthens bias for male leaders, this opens up several hypotheses.

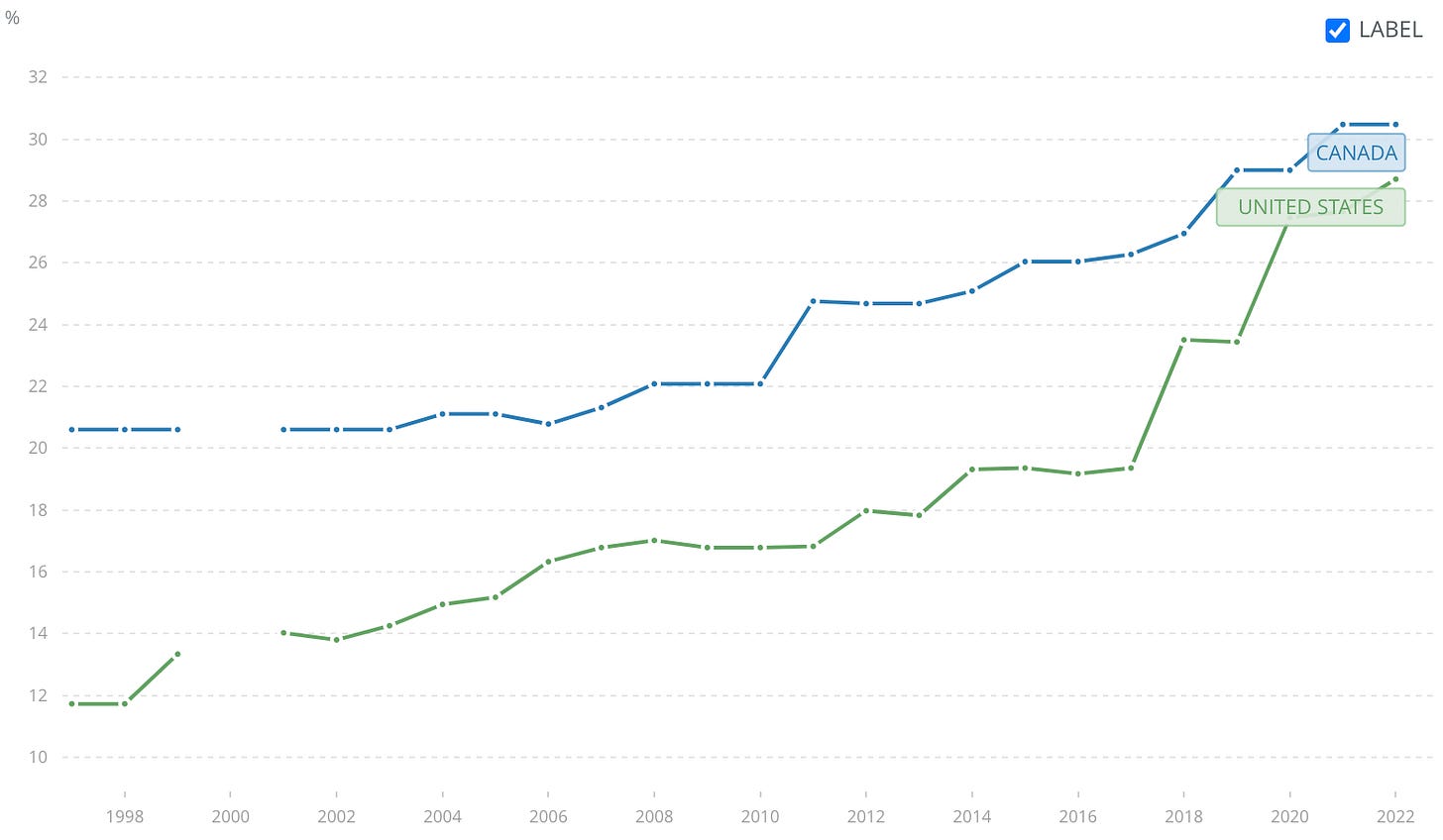

Canada and the US

Both have high rates of full-time female employment and majoritarian electoral systems. So why has Canada always had more women in power, including a gender equal cabinet? Could this have been enabled by the absence of geopolitical rivalries? Canada never formally joined the coalition that invaded Iraq. Instead of fixating on war, Canadian voters pushed their government to make childcare more affordable.

America’s long history of geopolitical rivalry (from the USSR to China) may have preserved a preference for a male “Commander in Chief”.

Central and Eastern Europe

Totalitarian communism suppressed civil society and suffocated feminist mobilisation. This inhibited pressure for more women leaders.

Russia’s Duma remains 84% male. I previously attributed this to its long history of totalitarianism. I now realise I was wrong.

Post-communist countries that joined the European Union and NATO have seen a marked increase in female representation. Women are now Presidents or Prime Ministers in Moldova, Estonia, Kosovo, Hungary, Lithuania, Slovakia, Georgia, and Serbia. As noted by Elena Roe, women have also served in these high offices in Romania, Estonia, Poland, Latvia, Croatia, Slovenia, Kosovo, Slovakia, Lithuania, Moldova, and Ukraine.

What explains this post-communist divergence?

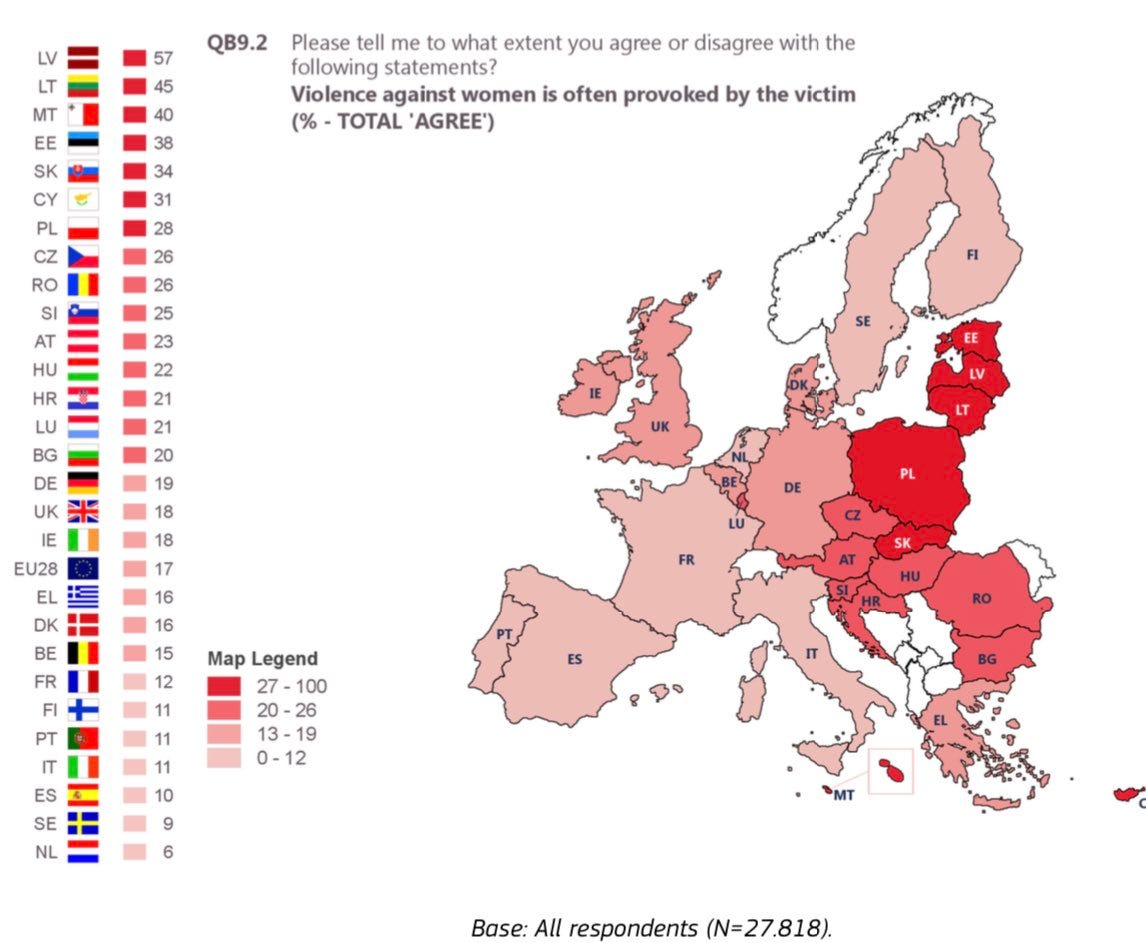

It’s not rampant feminism. The term remains toxic, gender ideologies are still relatively conservative, victims continue to be blamed for their own assaults.

Geopolitics is one possible explanation.

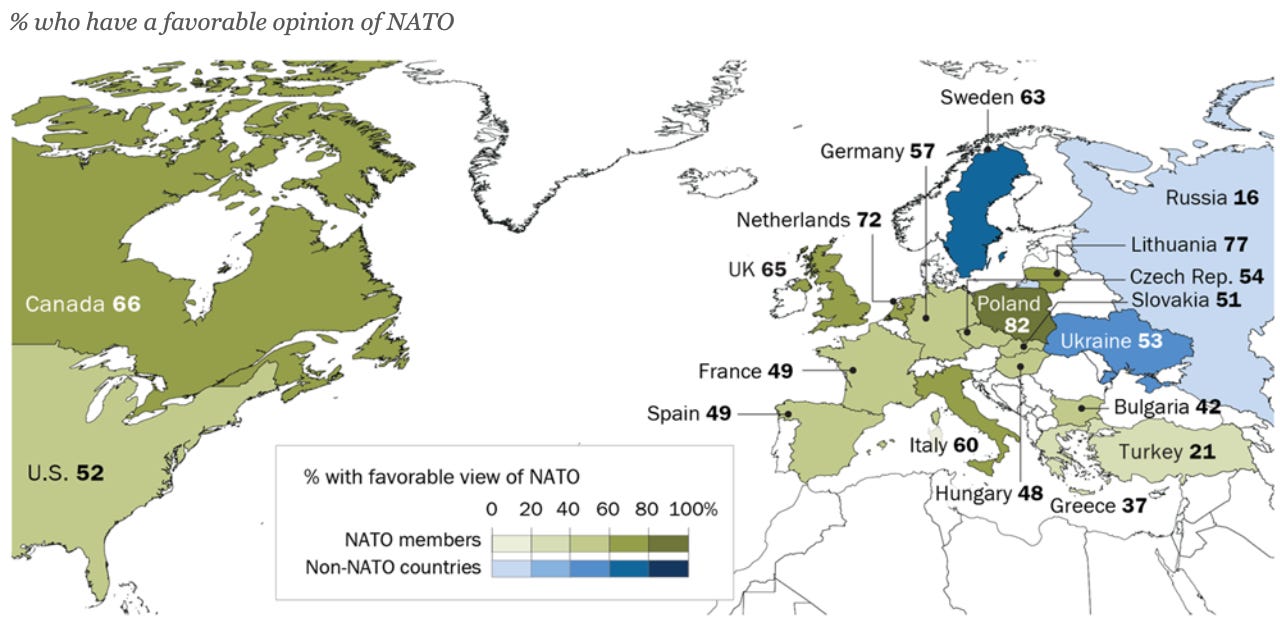

NATO protection may alleviate existential anxieties, reduce preferences for 'tough leaders', and thereby enable voters to seek politicians with other characteristics. Instead of being stigmatised as ‘weak’, women leaders may actually be valued as virtuous outsiders, cleaning up corruption.

Western and Central Europeans are formally protected by NATO. The overwhelming majority of Estonians see NATO as ‘the most important security guarantee’. They do not prioritise defence - as shown by recent polling by the European Values Survey (map below). NATO membership thus substitutes for tough male leaders.

Foreign policy was very marginal in Estonia’s 2019 Parliamentary elections. Voters happily elected Prime Minister Kallas (a keen proponent of NATO). After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, she actually became more popular! Just like a man!

Ingrida Šimonytė (Lithuania’s Prime Minister) was actually losing support before the Russian invasion, but then this turned! As if she was a man!

Russia is the exact opposite. Putin has built up a cult of war, strummed up victory parades, and cultivated imperial ambitions. Most Russians say strong defence is very important. The State Duma remains 84% male.

TLDR

When people are under attack, they usually want macho leaders.

There are exceptions - I have previously written about Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen, Queens of the Arabs, Queen Zenobia who led an army against the Roman Empire, and Hausa Queen Amina, who captured new territories. These are exceptions to the rule. Men, for the most part, are culturally celebrated as military strategists.

Given widespread preferences for wartime patriarchs, hostile external environments and terrorist attacks tend to erode public support for women. Cross-country regressions and natural experiments confirm this broader trend.

Many regions - not least the Middle East - continue to face major terrorist attacks. This may be entrenching patriarchs.

International security is thus an important pathway for female leadership. NATO may be the most powerful (though under-appreciated) force for female empowerment.

I realise I am enormously late to this but I was reading it as I was researching something a bit different - but what a pleasure to see the Hausa warrior Queen Aminah mentioned! I am a westerner who lived in Nigeria for three years not too many years ago for work. My then 6 year old daughter used to come home from the international school singing nursery rhymes about the great Queen Aminah. "She rode throughout the land, and she held her sword in hand, if you're proud of Queen Aminah shout hurray - HURRAY!"

My daughter still speaks the odd Hausa phrase now, something of great satisfaction and curiosity to the large diaspora from Nigeria which has arrived in my home country since our three years in theirs. It is interesting indeed that Nigeria both north and south, Christian and Muslim, possesses many heroic female folklore figures like Queen Amina, but this has not translated into women in positions of political power at all. It never struck me that women were particularly downtrodden in Nigeria, but certainly the tiny, tiny proportion of the elites that enter politics are almost always men. The few women who break through come from the exact same positions of immense privilege.

So this quick note is just to say that the mention of Queen Amina of Zazzau brought back some very happy memories of three years in a crazy country.

Hi, very interesting post.

I think it makes sense that in times of war or aggression societies prefer male leaders. For one, all societies choose to sacrifice their men when it comes to war. If somebody has to die or be killed, it will be a male (with all the exceptions you want). We're the expendable ones. (Won't go into the nature/ nurture debate about this.) But then, if societies view men as the natural warriors, well - you'll choose a warrior to lead you in war, right?

The second thing I'd like to comment on is regarding Estonia. I'm originally from Barcelona, but have been living in Estonia for a few years. The thing that always surprised both me and my wife is how "straight" male culture is in Estonia. We're used to BCN/ Spain where there is more divergence/ freedom in terms of male behaviors and attitudes. Here it's different. They're all like very well behaved, non-talkative, men from the 50s. I guess it's related to the previous point - Estonia is at the border of the West with 'the Barbarians', there still is compulsory military service for men, etc.

Also, prime minister Kaja Kallas is absolutely hawkish in terms of military, defense, Russia, etc. She's probably been able to stay popular by being more "mannish" than any other male leader on all these issues. She can overtake any other male leader on the right. So it's probably not about gender, but about gendered attitudes/ perceptions.

Anyway, I'm a fan, so thanks for posting!