Why Do Some States Protect Women While Others Enable Abuse?

Ideological Persuasion, Technology, and the Struggle for Safety

Anna Kendrick’s “Woman of the Hour” powerfully illustrates a chilling historical reality: how male violence was enabled by systems of impunity. The film spotlights how Rodney Alcala appeared on a national television show despite prior convictions, eager to claim more victims.

This isn’t just Netflix dramatisation - it reflects a critical truth. As American women increasingly stepped into the public sphere, eager to embrace newfound freedoms, they traversed male-dominated institutions, which enabled stranger violence.

Through my globally comparative and historical analysis, I identify two crucial mechanisms that improve women’s safety: persuasive feminist mobilisation and state capacity. Women’s movements must convince society at large that male violence is unacceptable and that institutions must reform.

But this virtuous cycle depends on women's capacity for ideological persuasion. Where women are constrained - whether by male honour or authoritarian repression - feminist movements cannot build broad-based support. Without this pressure, states remain unresponsive and abuse continues unchecked.

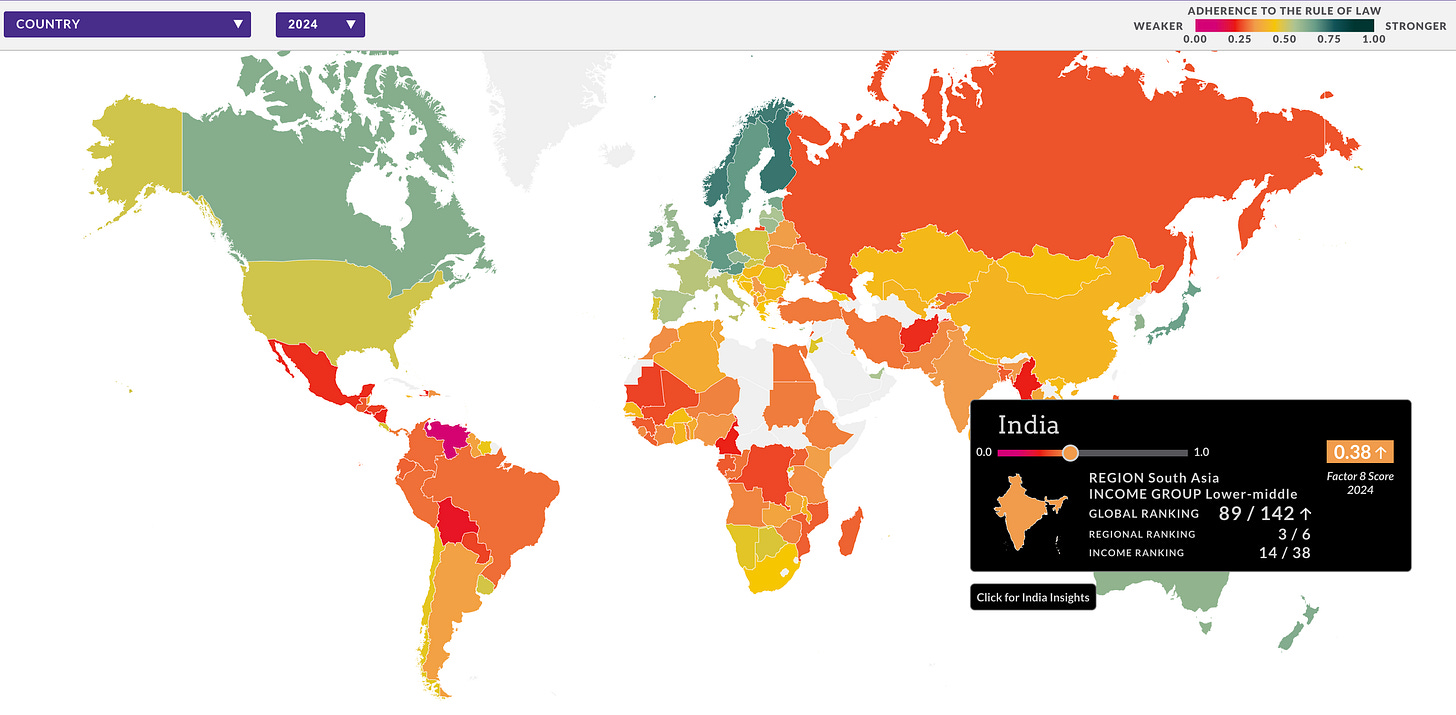

Patriarchal authoritarian states like Russia and China actively crush feminist activism while turning a blind eye to abuse. In India, caste strictures and an overburdened state mean that violence continues, while women cannot credibly threaten exit. Latin American women are free to protest en masse, but a wider environment of criminal violence still breeds dangerous machismo. Throughout, we see that women’s safety hinges on their ability to build consensus and secure state enforcement.

Modern technology adds another challenge: while innovations can enhance safety, they also enable people to retreat into ideological echo chambers, making it harder to convince the broader public that change is necessary.

Outline:

Women's safety requires persuasive feminist movements and capable states working together

West: Feminists forged consensus that male violence is unacceptable and pushed capable states to enforce protection

What did Acemoglu and Robinson get wrong?

Russia/China: Authoritarian states permit abuse

India: Caste strictures and male honour codes prevent women from building support

South Korea: Hostile sexism breeds impunity

Latin America: Weak states enable criminal violence

Technology: Makes consensus-building harder (echo chambers) but enforcement easier (surveillance)

Future: Schools and rule of law remain crucial for maintaining broad-based agreement

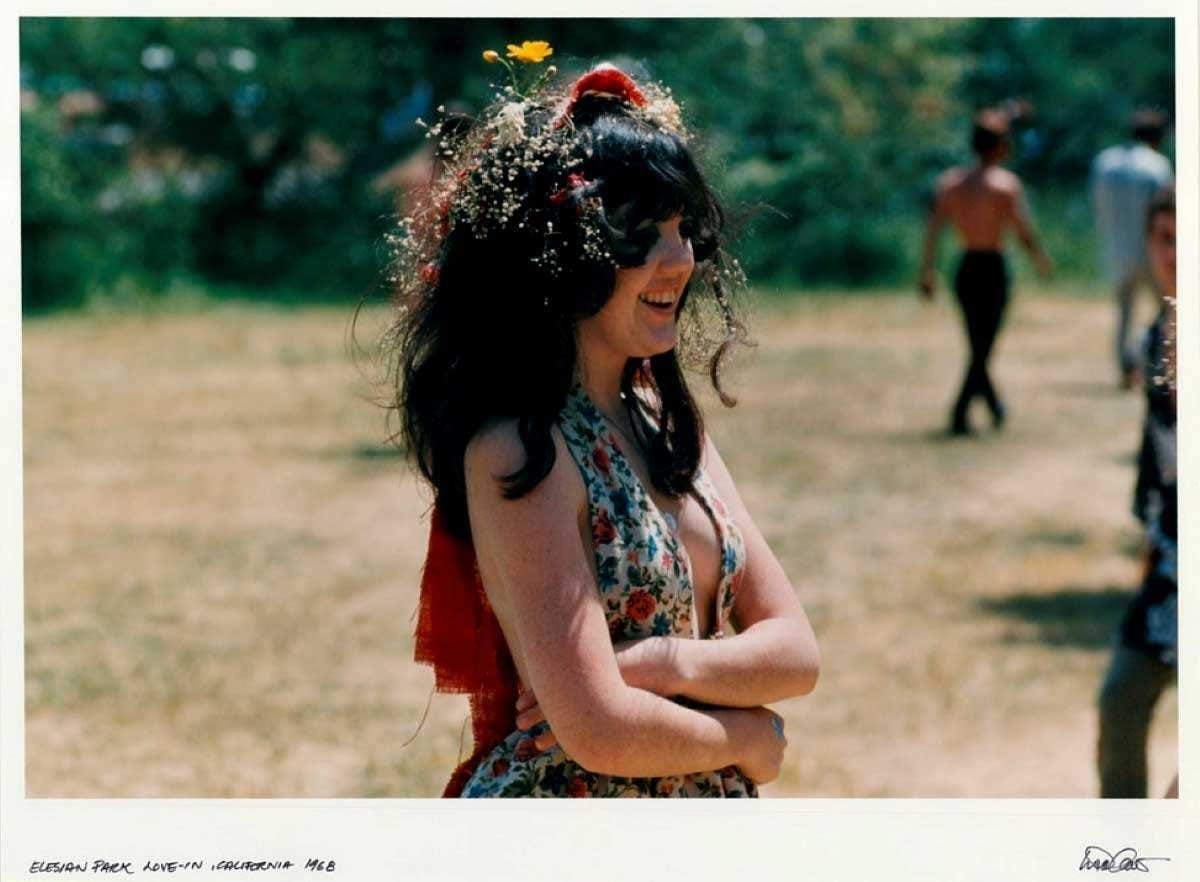

The Spirit of '68: Freedom Without Protection

The 1960s marked a profound shift in women’s freedoms right across Europe and North America. As women gained control of fertility, flocked to universities and forged careers, they got a taste for independence!

Rock and Roll celebrated a spirit of rebellion. This culture of youthful resistance was enabled by job-creating economic growth, urbanisation, democratisation, and the expansion of higher education. Students had the time, fraternity, and economic autonomy to think for themselves and organise for alternatives.

Yet this newfound freedom came with serious risks. Sexual liberation did not guarantee female safety. Young women wanted to enjoy the night like their male peers, but it remained very much a man's world. Rapes and murders were frequently reported across major cities. A woman who attracted attention only had herself to blame: "What was she wearing?", "Why was she out so late?" Objectors were derided as killjoys. This tension between growing freedom and persistent danger revealed a crucial truth: women needed both the liberty to move freely and the protection of strong institutions willing to defend their rights.

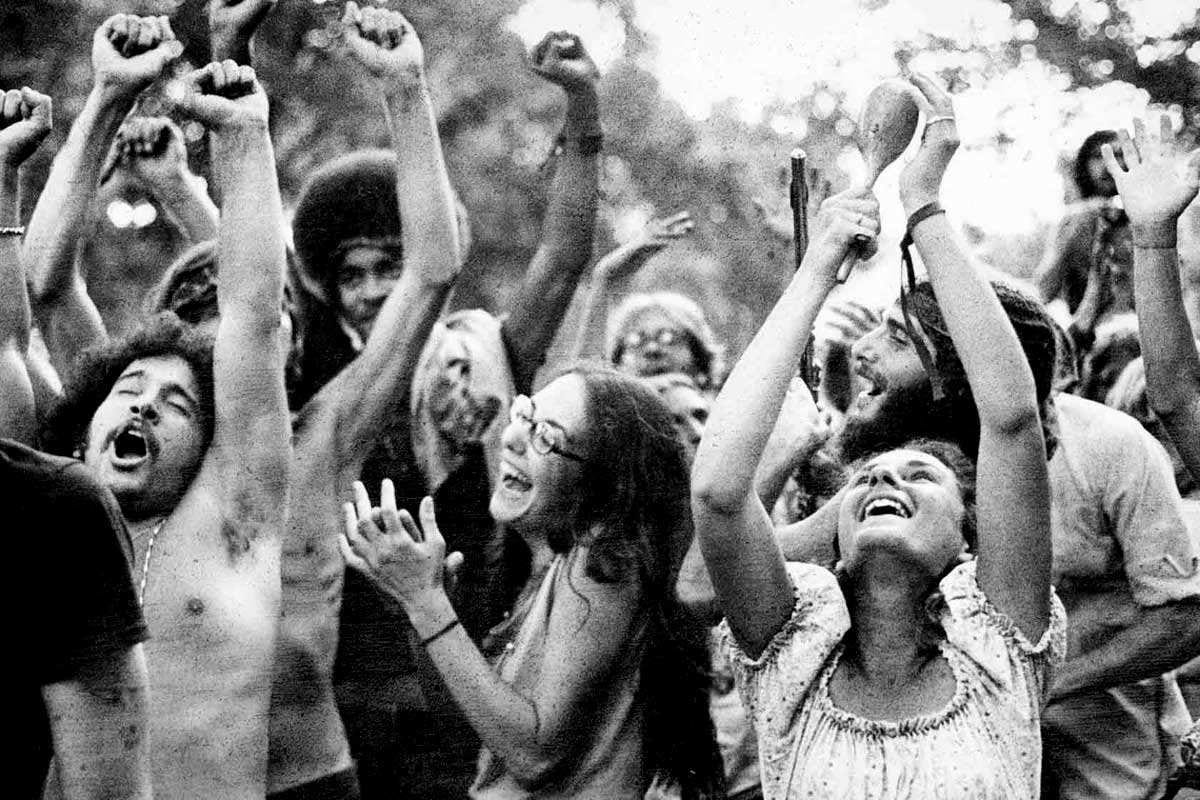

Mobilising for State Protection

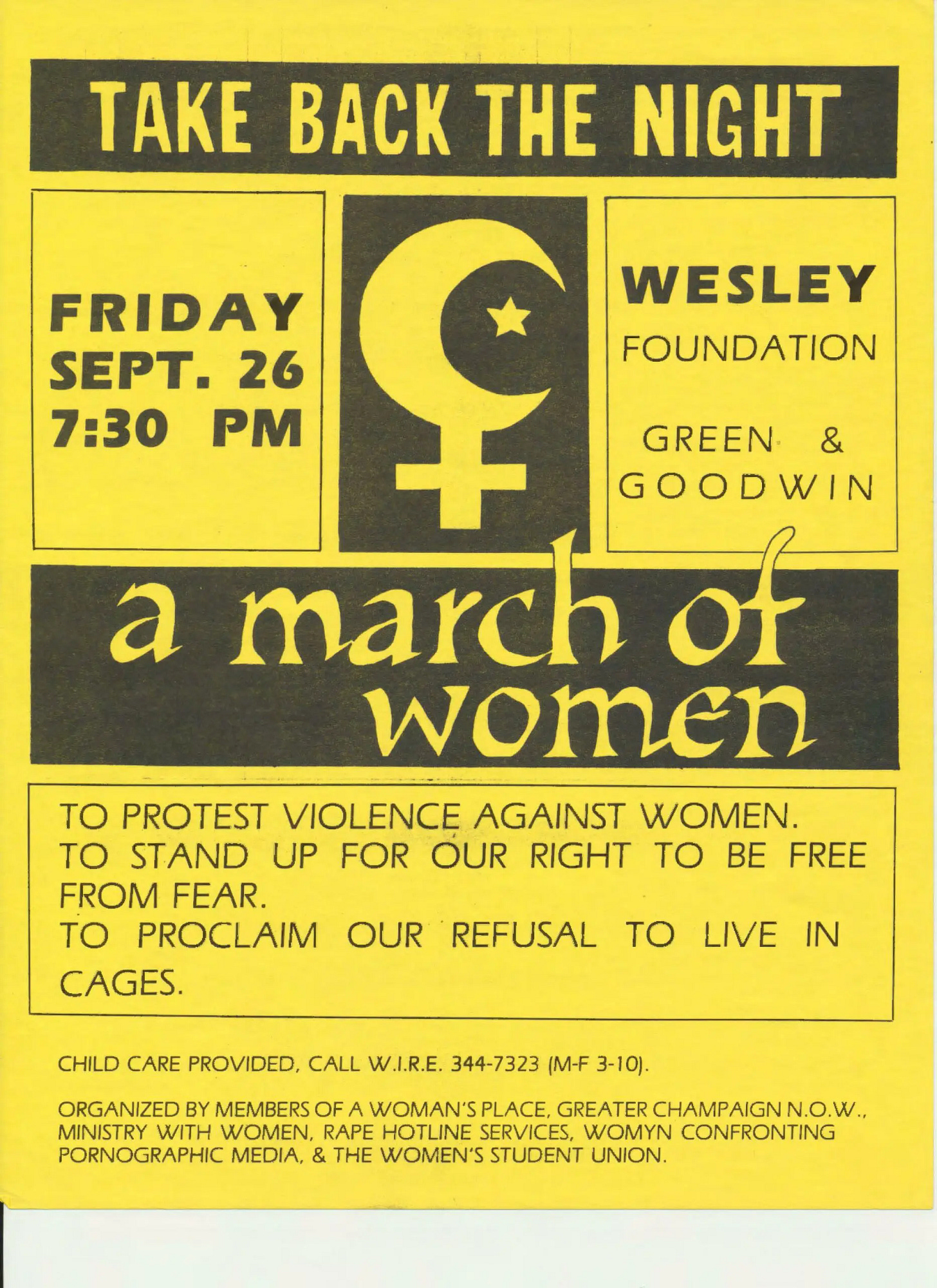

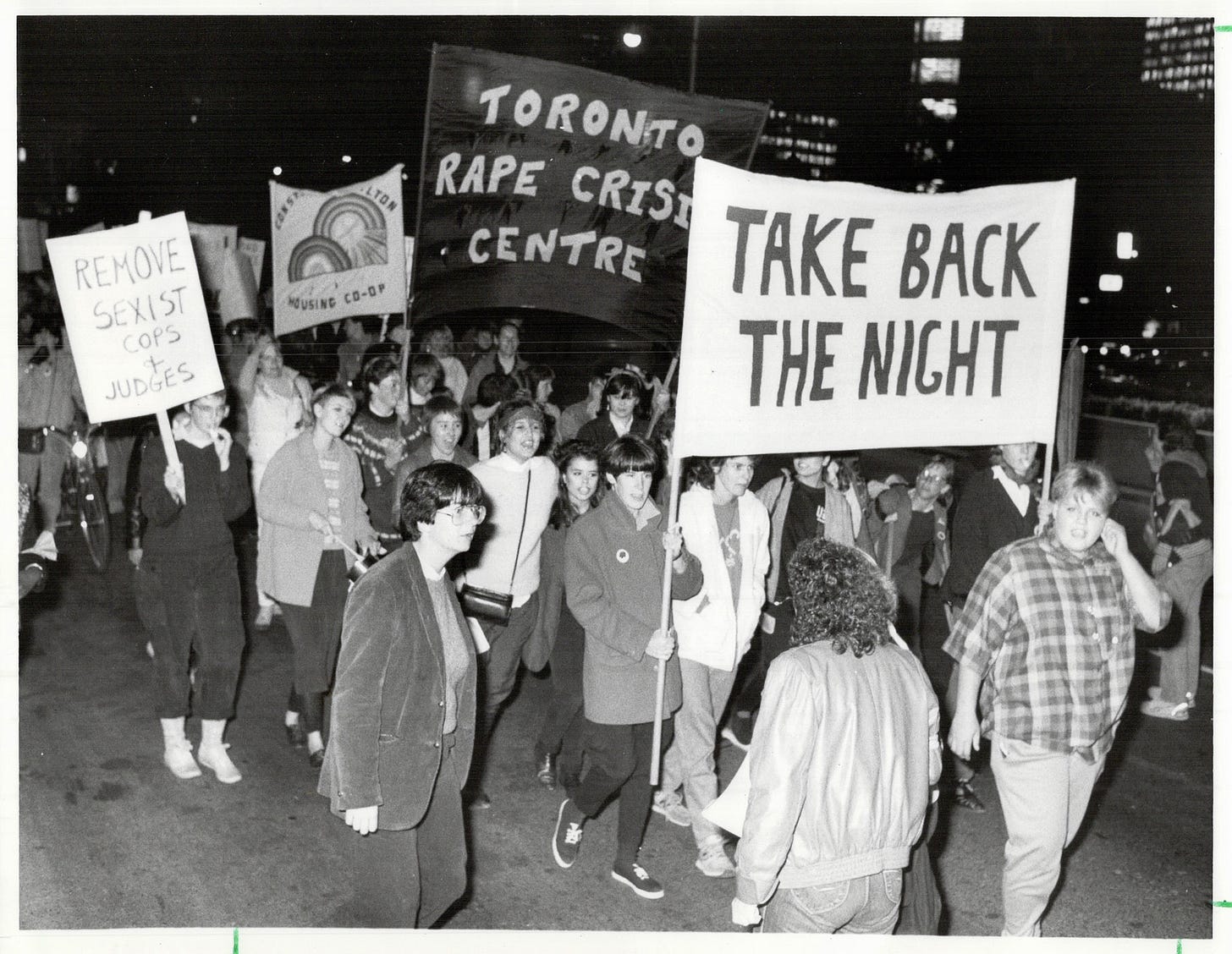

In 1976, a Tribunal of Crimes Against Women met in Belgium, much inspired by Bertrand Russell's people's tribunal on Vietnam. Over 2,000 women from 40 countries gathered to share tales of abuse and demand public safety. This marked the beginning of decades of feminist activism to “take back the night”. At hundreds of North American universities, women demanded “our right to be free from fear, to proclaim our refusal to live in cages”.

Organising together, women realised their collective strength. As one Swedish activist reflected: “I stood in a square in a sea of women... There were speeches, there was singing and it felt warm all over. I went from there as a strengthened feminist”. This peer support emboldened a sense of righteous resistance and belief that change was possible.

“Women’s committees” assembled in municipal governments across North America and Europe, commissioning studies on women's safety. Surveys revealed that almost 50% of women in Toronto felt unsafe in parking garages. Consciousness-raising groups, marches, councils and legal challenges exemplify what I call “Reverse Dominance Coalitions”. Refusing to be gaslit, women built righteous resistance.

Capable States and Public Safety

North America achieved a major fall in violent crime - owing to improved policing, prosecution, and prevention. But this wasn’t automatic. Feminist movements persistently highlighted violence against women, demanding that police forces treat rape and domestic violence as serious crimes rather than private matters. Constant pressure helped secure institutional reforms.

Since the 1980s, the US has seen a marked decline in serial killers - a triumph of both moblisation and modernisation. Yaksic and colleagues highlight the importance of technological advances, institutional reforms, and societal shifts.

Improved surveillance dramatically increased the risks of detection. Police forces evolved from jurisdictional conflicts to increased collaboration, more readily considering serial offender scenarios and using new tools like familial DNA. Police departments began clearing rape kit backlogs and using advanced forensic techniques, whilst harsher sentences kept potential predators incarcerated longer.

Society also became more distrusting, while parents were increasingly protective. Certain ruses that serial murderers previously used to lure victims became implausible as claims became easily verifiable online.

Economic growth is equally important. As incomes rose, women could afford their own cars, and ceased doing something rather risky: hitch-hike with strangers.

Continued progress is not inevitable

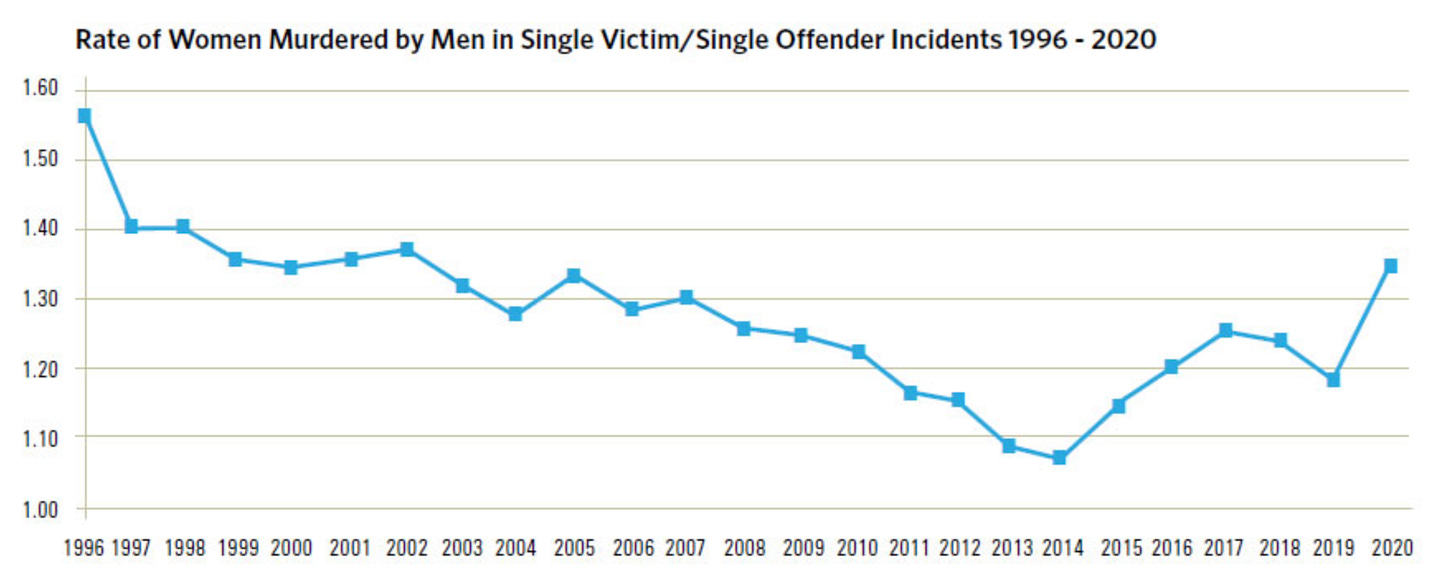

In the US, femicides have actually risen, while police clearance of reported rapes has actually fallen. A broad coalition of reform is crucial to reversing this trend and strengthen effective policing.

The UK's Push for Prevention

In the UK, feminist activism continues to drive institutional reform. Where women were once told to moderate their own behaviour, advocacy has successfully shifted responsibility onto government and firms.

New legislation requires employers to proactively prevent sexual harassment before it occurs. Companies must identify risks - particularly in situations involving power imbalances or alcohol - and take preventive action. If they fail, tribunals can increase compensation to victims by 25%.

British Transport Police now displays posters across train stations emphasising zero tolerance. The Greater Manchester Authority runs campaigns condemning male harassment.

Though challenges remain, these are examples of how feminist pressure combined with responsive institutions can enable greater safety at work and on the move.

What did Acemoglu & Robinson Get Wrong?

Acemoglu and Robinson's “The Narrow Corridor” offers a useful framework for understanding improvements in women's safety: liberty requires strong states and strong society.

Though they don’t explicitly discuss gender-based violence, their theory provides a useful foundation. The dramatic fall in serial killings stemmed from enhanced state capacity - with better policing and prosecution - secured through sustained feminist pressure.

However, their model needs refinement. ‘Strong societies’ don't automatically advance women's liberty - they may instead champion religious restrictions or hostile sexism. Some societies with vibrant civil society, like South Korea or Indonesia, still permit unchecked violence.

What matters is not just social unity but ideology.

This dual requirement - persuasive feminist movements and capable state institutions - helps explain why progress remains so uneven globally. Without both elements working in concert, patriarchal impunity proves remarkably resilient.

The Challenge of Building Both Freedom and Protection

Totalitarian Communist & Post-Communist Repression

Totalitarian Communist regimes repressed civil society in order to buttress their rule - in the Soviet Union, China and Cuba. Dissidents were purged or sent to forced labour camps, while informants instilled fear and self-censorship.

In Russia, decades of dictatorship stunted associational networks. Civil society membership remains systematically lower in post-communist countries, whilstAnti-democratic attitudes are highest among those who lived under communism.

Russia exemplifies how authoritarian control prevents the emergence of feminist movements that could lobby for accountability. Without this pressure from below, police routinely disregard victims, who in turn distrust the police.

"Come see us after he’s killed you" remains a grimly accurate characterisation of official attitudes. In 2017, Russian legislators actually decriminalised domestic battery. Half of all married women have been beaten by their husbands, yet many feel fatalistic presuming nothing can mitigate pervasive alcoholism and abuse.

China: Authoritarian Repression

Official statistics indicate 38% of Chinese women experience intimate partner violence, while the state either turns a blind eye or even blames victims.

In 2020, Shi slapped and strangled his girlfriend. Hong escaped and reported him to the police. She recorded that conversation then posted it online. Many Chinese people were aghast at how she had been dismissed, scolded and berated by the police. But even after public scrutiny, Shenzhen officials only fined him $33 dollars.

The Chinese Criminal Law of Abuse (2020) states that “beating, occasional starving, occasional mobility-forbidding do not constitute a crime”. Slapping the face is not a crime. IPV is not criminalised unless it involves mutilation. Even if family violence is judged ‘severe’, punishment is usually capped at two years imprisonment.

The police and law courts are totally unsympathetic, details Tiantian Zheng. Only 3% of divorces filed for IPV are awarded. Police inaction fuels despondency:

“What’s the point of getting the Personal Safety Order? Even if I get it, I still won’t be protected by the police. He’s going to beat me more” - Xiao Chen.

“I now live in fear everyday, but it’s useless to go to the court or the All China Women’s Federation again for help” - Ying.

Victims are trapped in abuse. This is a direct consequence of repression.

Now, Beijing clearly cares about public opinion, but here’s where we need to realise that society is divided. Social media is also strongly sex-segregated, with men favouring sites like Baidu Tieba. Echo chambers reinforce societal divides. Patriarchal entitlements are cheered by all the men in the room. If a culturally homogenous group applauds a singular perspective, it appears entirely legitimate.

South Korea: Sexism and Impunity

While South Korea has both a strong feminist movement and the technological capability to combat abuse, widespread animosity to feminism means that the state largely turns a blind eye. Violence continues with impunity.

A recent wave of sexually explicit deepfake images has rocked the nation, with perpetrators using girls’ school photos and social media selfies. A Telegram channel with over 220,000 participants was reportedly being used to create and share AI-generated porn. Users could upload photos and within seconds create explicit content featuring their friends, classmates, or romantic partners.

Hawon Jung's “Flowers of Fire” details how the rise of spy-cam pornography reflects deeper misogyny, with men sharing footage celebrating their ability to conquer and humiliate.

Yet even women survivors present evidence, the police are often dismissive. On the rare occasions that cases made it to court, perpetrators are given impunity. As one judge concluded:

“The accused married only recently and has a job—meaning there’s a chance he could lose his job if he is sentenced to a prison term,” [so we should give] “a special leniency.”

One man who took 1,2690 upskirt shots with camera mounted shoes was given a suspended jail term. He went on to become a taxi driver, install a spycam in the backseat and took upskirt photos of over a hundred female passengers.

Why is South Korea’s capable state so unresponsive?

South Korean move freely and have mobilised en masse, so why are authorities not getting into gear? A key constraint is that feminist mobilisation actually triggered patriarchal backlash. Society is deeply divided.

As long as Korean men continue to dominate management and socialise with other men, they are immersed in cultures of self-righteous sexism. 80% of twenty-something men believe there is serious gender discrimination against men.

If you look at the timings, it is precisely after 2016 feminist activism when young Korean men lurched to the right. Political and cultural entrepreneurs mobilised frustrated young men - many of whom are struggling in an adverse dating market. And since everyone is connected on their own smart phones, free to build their own subcultures, misogynists can create online spaces that legitimise misogyny.

“Feminists are a social evil”, said Bae In-kyu, 31.

Yoon Suk Yeol launched a successful campaign for president, by politicising mandatory conscription and defining himself as an anti-feminist.

South Korea therefore demonstrates a powerful truth: state capacity, democracy and economic development are not enough for women’s safety. Given the tide of hostile sexism, and social bifurcation, politicians actually have every incentive for inaction.

India: State Incapacity and Male Honour

India’s cities are widely seen as unsafe for women. This stems partly from state incapacity, as well as male honour codes and caste strictures, which inhibit feminist mobilisation.

Roychowdhury’s brilliant new book - “Capable Women, Incapable States” - reveals how several factors combine to maintain impunity. State institutions are severely understaffed, with one police officer per 720 civilians and massive case backlogs.

Even when victims overcome family pressure to seek help, they encounter a system that routinely dismisses their complaints. Consider the case of Uma, a Brahmin woman who approached the police alone and was told to go home and reconcile with her abuser.

Police officers, feeling overworked and under-resourced, routinely absolve themselves of responsibility. In their view, women will inevitably return to their husbands. They can usually get away with ignoring claims, so they only act when facing pressure.

Payel experienced similar institutional neglect. She had fled her abusive husband and wanted to retrieve her dowry. Despite visiting the police with visible wounds from where her husband had scorched her with a hot spatula, she was turned away because the police were ‘too busy’.

Cultural factors are equally paramount. Since male honour depends on female chastity, and fears of violence loom large, young women may face paternalistic restrictions.

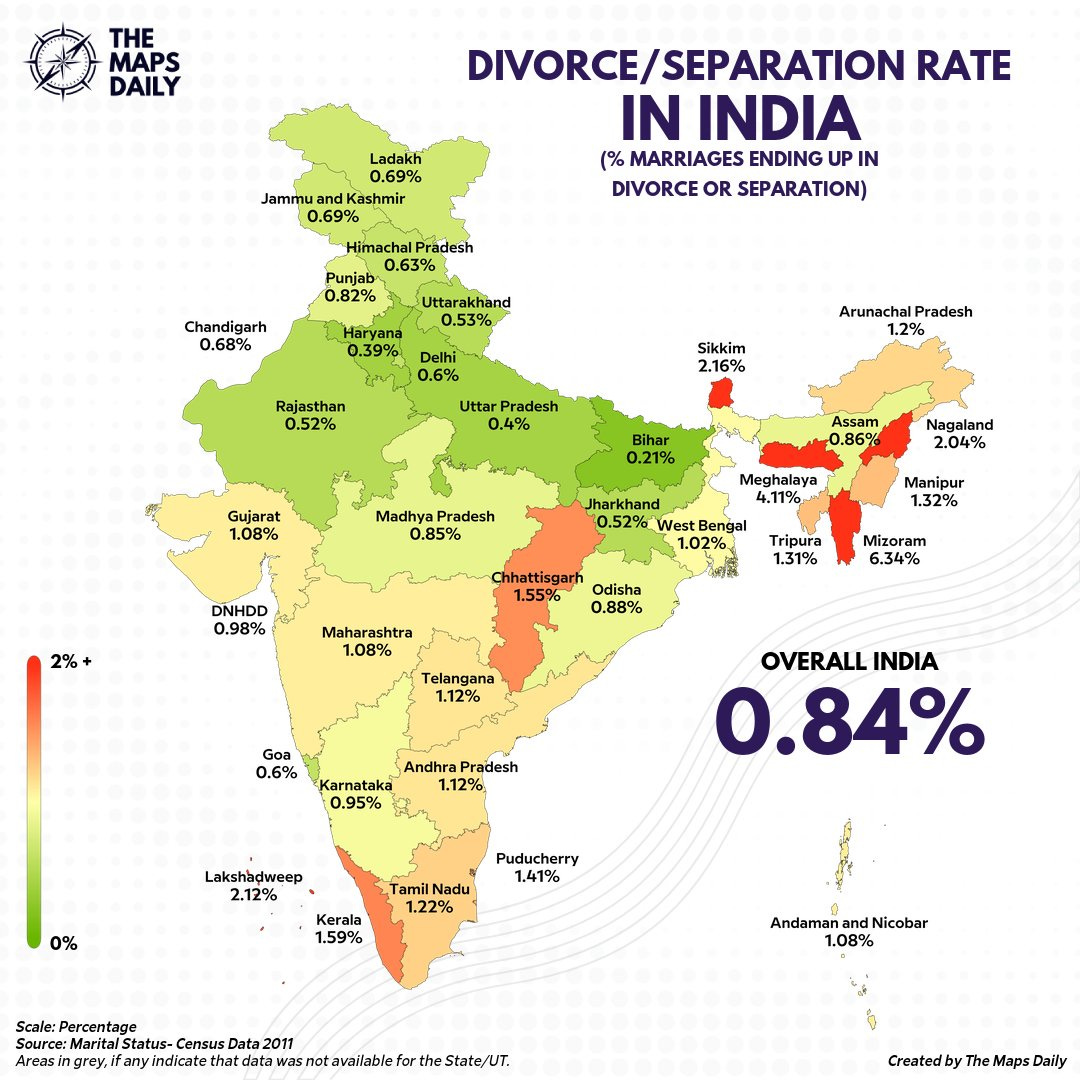

The caste system also comes into play, as these trusted networks of cooperation are preserved through strong stigmatisation of divorce. Girls are socialised to marry, please their in-laws and stay put. Women’s inability to credibly threaten exit helps explain high tolerance of abuse - with 52% of women believing wife-beating can be justified. I call this “The Patrilocal Trap”.

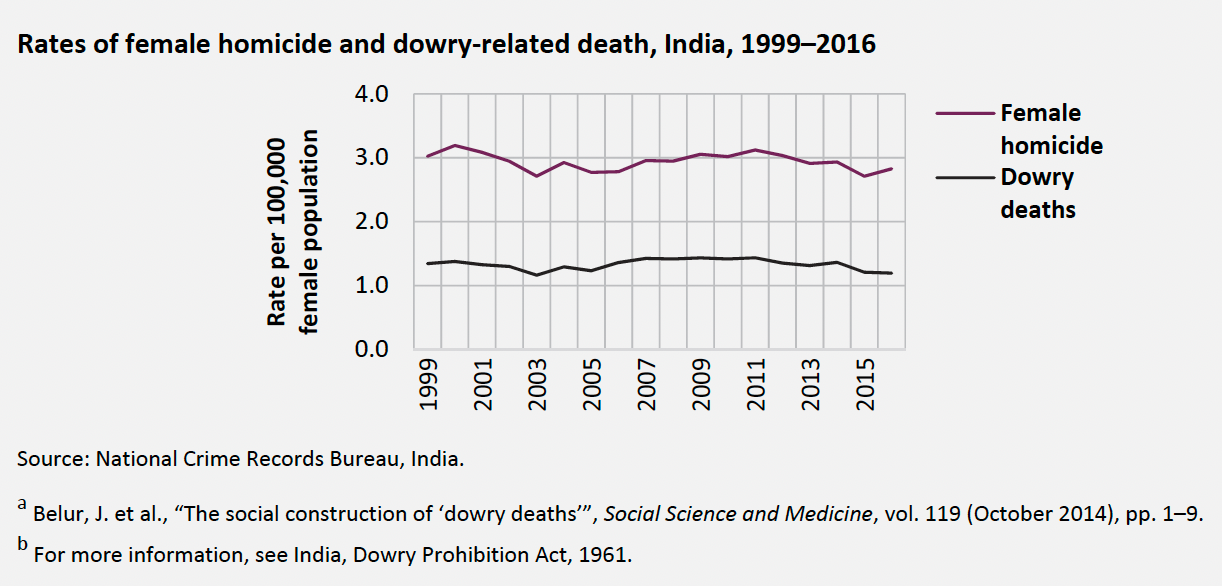

Despite strong rights on paper (dowry is illegal, dowry deaths are specifically identified in the penal code), dowry deaths account for 40-50% of all female homicides recorded annually in India. This rate remains stable.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Where Weak States Enable Criminal Violence

Unlike post-communist states or regions dominated by male honour codes, Latin American women can mobilise freely. But homicides loom large - amid ineffective governance and rampant criminality.

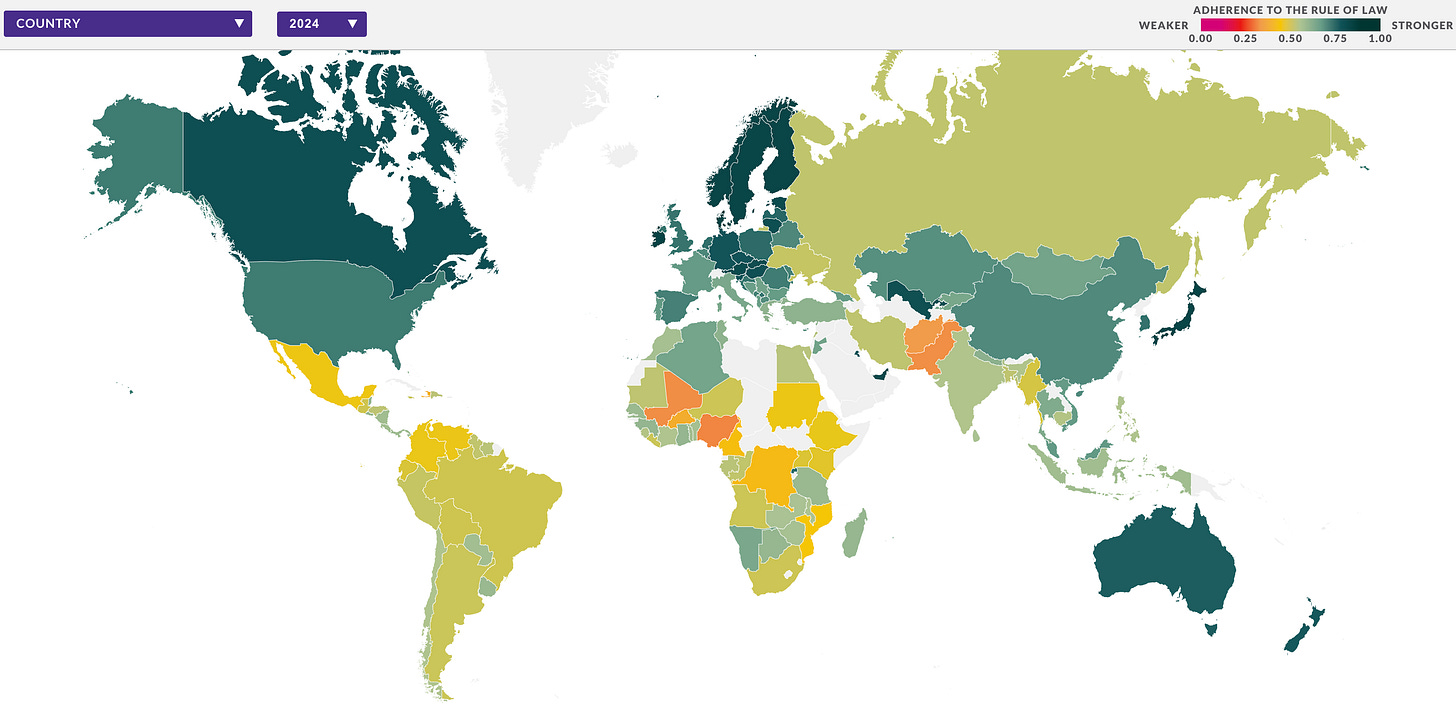

As you can see from the maps below, Latin American governments lag behind Europe in terms of territorial control and state capacity.

Where state security forces are ineffective or complicit, rival gangs fight over lucrative drug routes. Deborah Yashar's brilliant book, “Homicidal Ecologies”, reveals this crucial dynamic. Guatemala provides a telling example - when drug gangs relocated their operations there in response to crackdowns in Mexico and the Caribbean, homicide rates surged as rival groups fought over territory.

Nicaragua offers an important counterpoint that proves the rule. Despite being one of Central America's poorest countries and geographically positioned for drug trafficking, it maintains lower homicide rates than its neighbours. Yashar attributes this to its relatively professional and community-oriented police force - a legacy of Sandinista reforms that created a more independent, service-oriented institution. With a police force capable of maintaining order and actively working with communities, criminal organisations find the environment less hospitable, and rates of violence - including gender-based violence - remain comparatively lower.

Where states cannot effectively enforce laws or provide basic security, rival gangs compete for dominance. The resulting culture of violence and machismo creates an environment of generalised violence.

Recent estimates indicate that approximately 43 million women between ages 15-49 - one in four LAC women - have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner at least once in their lifetime. In 2021 alone, at least 4,473 women were victims of femicide across the region - averaging 12 gender-related killings per day.

Strong States & Feminist Movements

Women's safety ultimately requires mass ideological persuasion - shifting the blame from victims to perpetrators. The Western transformation succeeded because feminist movements built widespread consensus that men's violence is wrong, while capable states enforced new protections.

When either element is missing - whether through authoritarian suppression, state weakness, or female seclusion - violent offenders persist with impunity. The Western transformation wasn't inevitable - it required sustained feminist mobilisation pushing states to reform. Gender equality thus requires both dimensions: building state capacity whilst preserving democratic space for feminist movements to flourish.

21st Century Challenges

We are living in an era of massive technological revolution, but whether this enhances women's safety ultimately depends on ideology and use. In the West, feminist pressure has led states to deploy surveillance cameras, DNA databases, and digital evidence collection to catch perpetrators. But where patriarchal cultures persist, misogynists leverage these same innovations - creating deep fake pornography to shame and humiliate.

A further challenge concerns online communications. Everyone can retreat into their own echo chambers, making it harder to build societal consensus. 51 men are currently on trial in France for their alleged attacks on Gisèle Pelicot. While she defiantly declares that ‘shame must change sides’, her compatriots can choose to look away, preferring to watch matches with football stars like Kylian Mbappé. Seldom seeing peer disapproval, it's much harder to build consensus.

So how can we maintain widespread condemnation of male violence? Inclusive schools to foster common values, combined with robust rule of law to protect everyone, will likely remain crucial for upholding women's safety.

Related Essays

P.s. Many of these ideas have been inspired by conversations with Daron, so I share them in celebration of the Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson Nobel.

Also, watch “Woman of the Hour” on Netflix! It’s great!

Western feminism is more concerned with promoting female CEOs,even against their preferences,than women's rights and safety across the globe.

What happened in the US in 2014? Why did the proportion of crimes solved decline in the US?

Edited to add: What makes South Korea different from Japan or Taiwan in terms of backlash to feminism? I know that the countries are different, but it seems to me that much more must be going on in South Korea for it to have the dynamics that it does, and that are not seen nearly so strongly in other democratic countries in Asia.