Beyond Brawn: Reimagining Masculinity

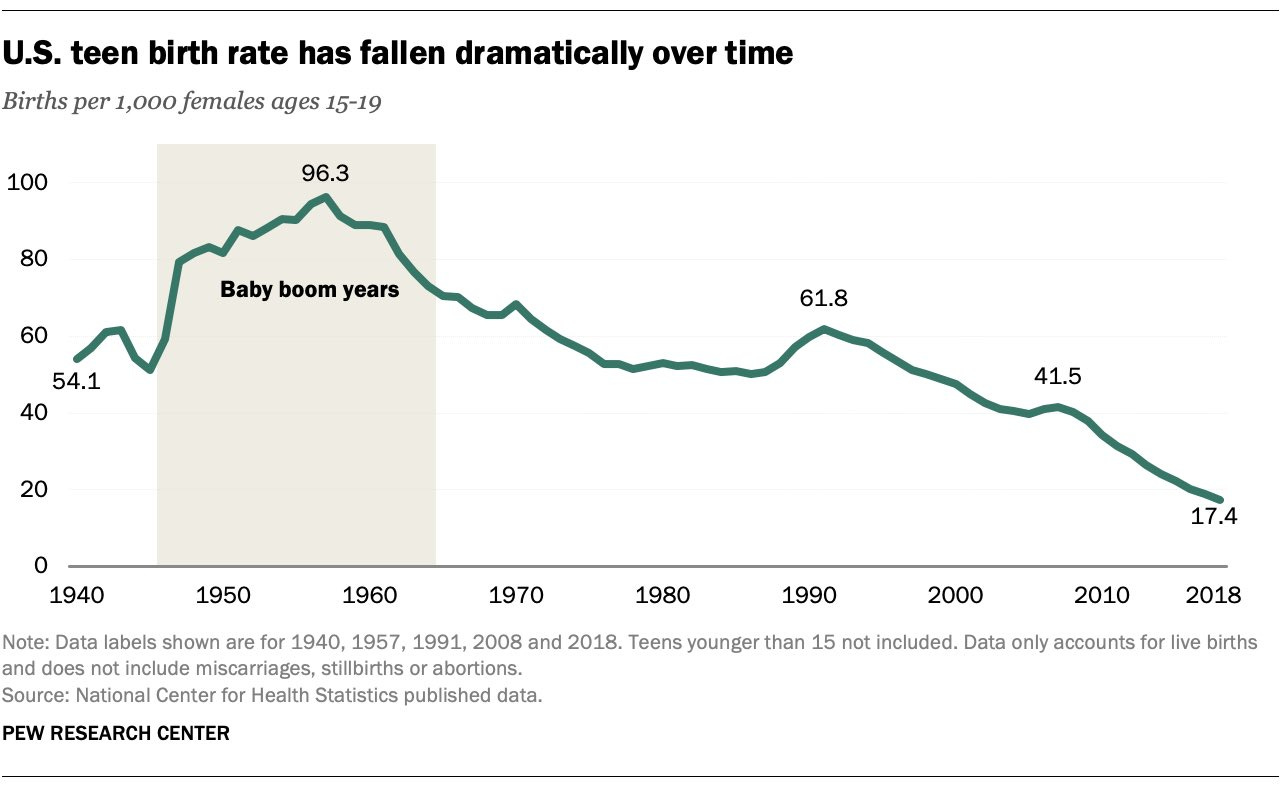

Over the past 50 years, new technology and cultural narratives have worked in concert to fuel women's success. With contraceptives enhancing control and media raising ambitions, teenage pregnancy plummeted. Armed with degrees, women stormed the gates of law, medicine, and management.

Yet technology is pushing in the opposite direction for working-class men. Automation has devastated traditionally masculine work, as hyper-efficient robots and foreign competition displace jobs in manufacturing and construction. For the least educated men, the alternative is often gig work: Instacart-intensive solitude, rushing to deliver orders

This is a tale of two uneven transformations, with the least-educated men lagging behind.

But is it just about technology?

My globally comparative research reveals something crucial: whether people seize new economics opportunities depends on both technology and culture. Consider women's revolution. Yes, contraceptives helped control fertility, but free time wasn't the only factor. The West never idealised female seclusion, and Hollywood actively celebrated ambitious, go-getting women making their mark. Prestige bias encouraged wider emulation, resetting expectations.

Could the lessons from women's liberation - this powerful combination of technological and cultural change - help men thrive in our changing economy?

The Power of the Pill

Goldin and Katz's (2002) landmark study revealed how oral contraceptives revolutionised women's career trajectories. Before the pill, young women faced a stark choice: pursue extended professional education or start a family. An unplanned pregnancy could derail years of investment in medical or legal training.

The pill fundamentally changed this calculus. Women could now reliably plan when to marry and have children whilst investing in their careers. The timing proves telling—as the pill became widely available to young, unmarried women in the late 1960s, female enrolment in professional programmes rose sharply.

This transformation worked through two key mechanisms. First, it directly reduced the risk associated with career investment by giving women reliable control over fertility. Second, it triggered an indirect effect through the marriage market—as more women delayed marriage to pursue careers, it created a more robust marriage market for career-oriented women, reinforcing the trend.

But the pill's success wasn’t purely technological - it worked in concert with shifting media narratives.

A wealth of research in the US has further demonstrated the power of the pill. Bailey, Guldi and Lindo (2017) show that when state laws allowed doctors to prescribe contraception to young unmarried women, use before age 21 increased by approximately 40% - and nearly doubled in metropolitan areas. In their early twenties - crucial time for career investments - women gained control over their bodies.

Clever women from ordinary backgrounds benefitted most - by their forties accumulating 3,500 more work hours and earning 20% higher wages.

Early access to the Pill explains about one-third of the wage gains for 40-year old women born in the mid-1940s and early 1950s. Around two-thirds of this ‘Pill premium’ came through greater work experience, with the remaining third reflecting more education and better jobs. Overall, the Pill accounted for roughly 10% of women’s wage convergence with men in the 1980s and 30% in the 1990s.

Cultural Aspirations

The risk with country case studies is that they tend to omit underlying culture, which exerts an unrecognised influence. Fertility has also plummeted in the Middle East and South Asia, yet female employment remains stubbornly low. This is because male honour depends on female seclusion.

Culture matters - both in terms of each society’s spectrum of permissibility and subsequent struggles for ideological persuasion. At the turn of the 20th century, Europeans and Americans idealised the cult of domesticity. Women’s primary duty was in the home. Culture has shifted dramatically - through persuasive story-telling.

Since the 1960s, one of humanity's greatest strengths - our ability to tell transformative stories - has revolutionized how we imagine women's lives. From Mary Tyler Moore to Battlestar Galactica and Scandal, popular shows actively celebrated female action-heroes, demonstrating their prowess. The cultural revolution didn't stop there: TV also destigmatised contraceptives and sexual freedoms.

Gripping television creates immersive experiences that temporarily transport us to imagine something different. Transfixed by compelling drama, we suspend disbelief and invest emotionally. Our visceral reactions - gasping in shock, tensing with fear, tearing up with sadness - reveal how deeply we connect with these characters.

This immersive quality makes television particularly effective at fostering empathy and normalising social change. When audiences repeatedly watch women succeeding in prestigious domains, these narratives feel achievable.

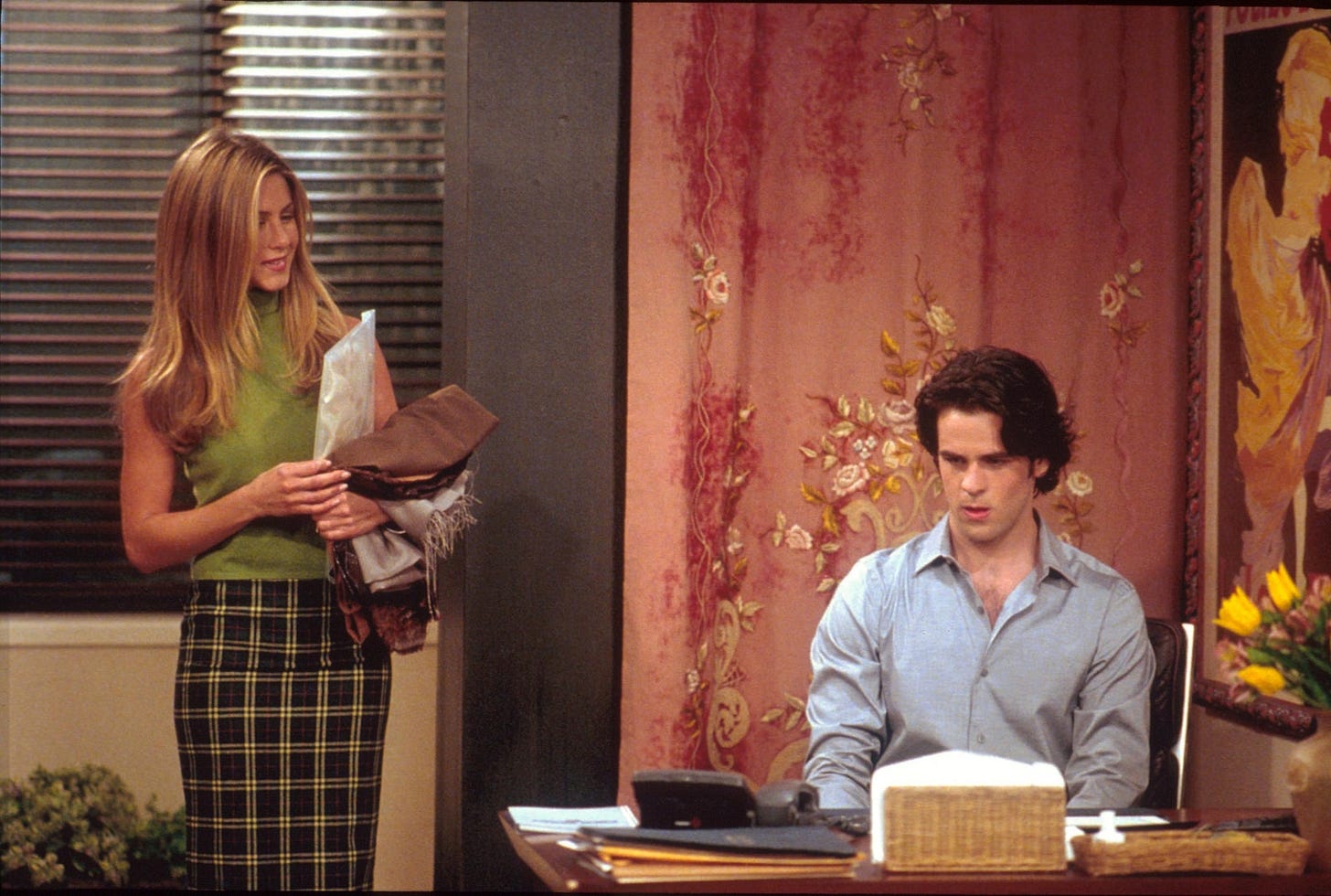

Consider Rachel Green’s journey in Friends. When she ultimately becomes an executive at Ralph Lauren, she is beautiful, glamorous and successful (with a male PA). The designer brand actually partnered with Warner Bros to create a 'Wear to Work' collection based on her character, featured in Vogue.

Go to any museum in the West, you’ll be sure to see an exhibition trumpeting women at the vanguard. At Stavanger’s maritime museum in Norway, visitors encounter Frida Dahlberg - an intrepid pioneering radio operator working cargo liners to West Africa in the 1950s. Western culture continues to celebrate women breaking barriers.

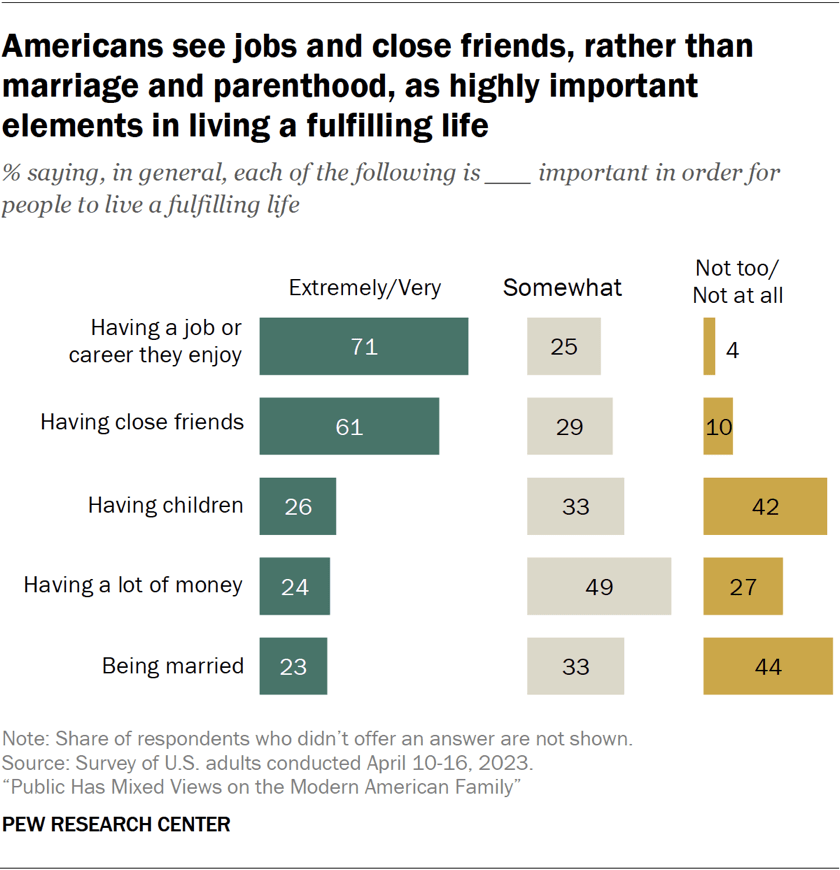

Goals have changed

Alongside shifting media narratives, ambitions are changing. 71% of Americans now say that a fulfilling life principally requires an enjoyable job. The cult of domesticity has given way to careerism.

Teenage pregnancy is down

While the pill provided the means to prevent pregnancy, television and film helped shift aspirations. Through this combination of technology and cultural narratives, the constraints on female ambition were kicked away.

Instead of getting pregnant at 16, women increasingly pursue degrees.

The Male Challenge

As our economies increasingly reward skills, the least educated men are struggling.

In the UK, boys are nearly twice as likely to face school suspension and struggle more with reading and writing benchmarks. These early educational challenges cascade into lower university completion rates—across many developed economies, men now lag behind in higher education.

Educational deficits interact with labour market changes. Globalisation and automation have weakened demand for jobs in manufacturing. Charles and colleagues find that US areas more exposed to manufacturing decline saw steeper drops in employment rates and annual hours worked. This impact intensified after 2000, when import competition and automation accelerated plant closures.

The remaining manufacturing jobs increasingly demanded higher skills, leaving less-educated male workers particularly vulnerable. While both men and women in automation-affected areas were more likely to pursue college education, the effect varied by gender - men often remained in declining sectors.

A Crisis of Status

The impact on relative earnings tells a stark story. In 1980, white men without college degrees earned above the average American worker. Factory supervisors made more than early computer programmers, managing assembly lines and shop floors during the final days of US manufacturing might.

The relative wages of production workers have fallen well below average wages. They've been surpassed by college-educated women, registered nurses, and dental hygienists, while computer programmers' earnings have soared.

Loss of Pride

This isn't just about money - it’s about relative status. As Arlie Hochschild details in her new book, when men languish in work, it wounds their pride.

A generation ago, unionised factory work offered training, benefits and decent pay to men straight out of high school. In Michigan, inland lakes are dotted with vacation cottages built for blue-collar workers. A factory job could buy a home, a boat, and send the kids to college. It offered not just income, but a sense of being useful to family, community, and country.

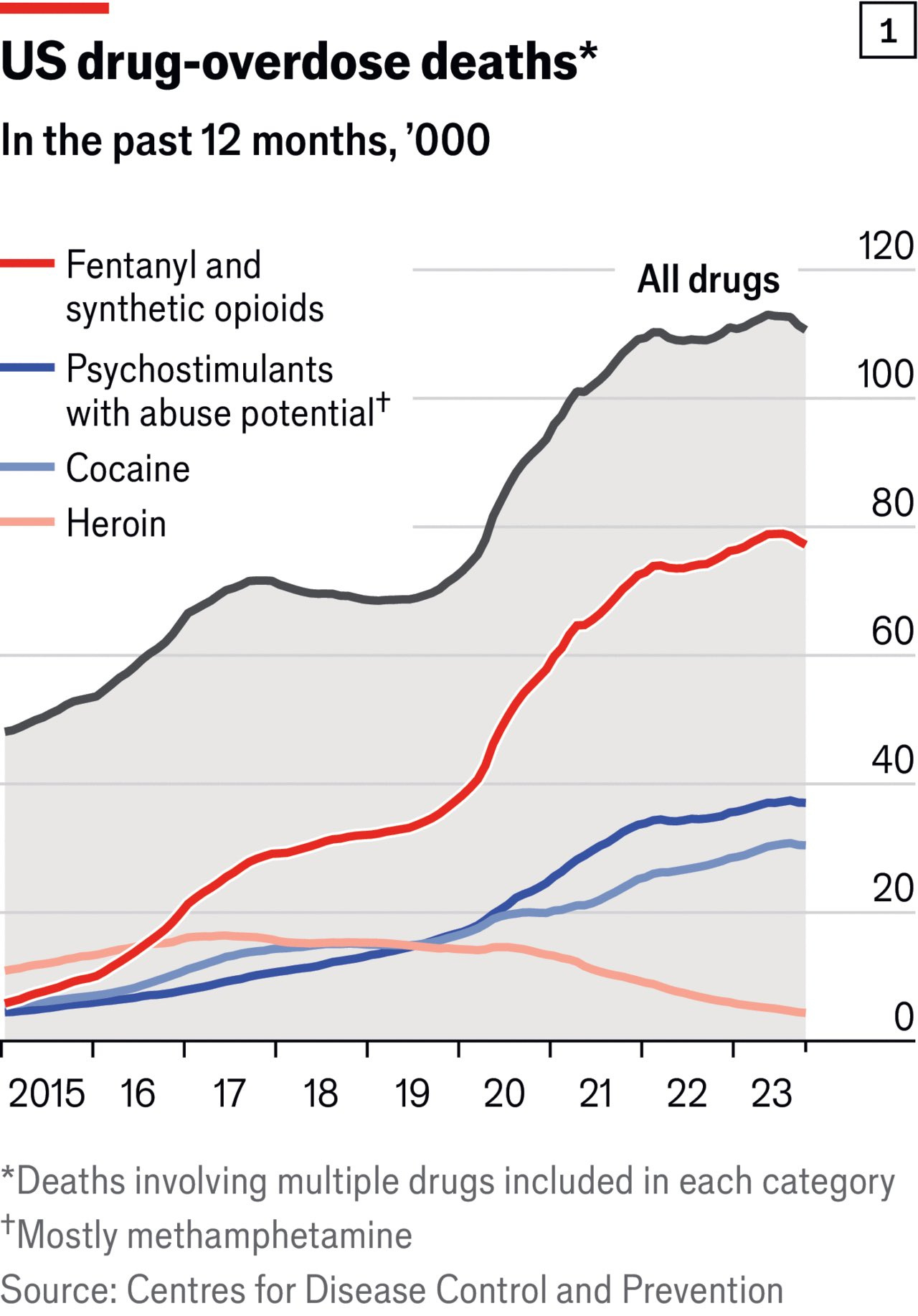

Deaths of Despair

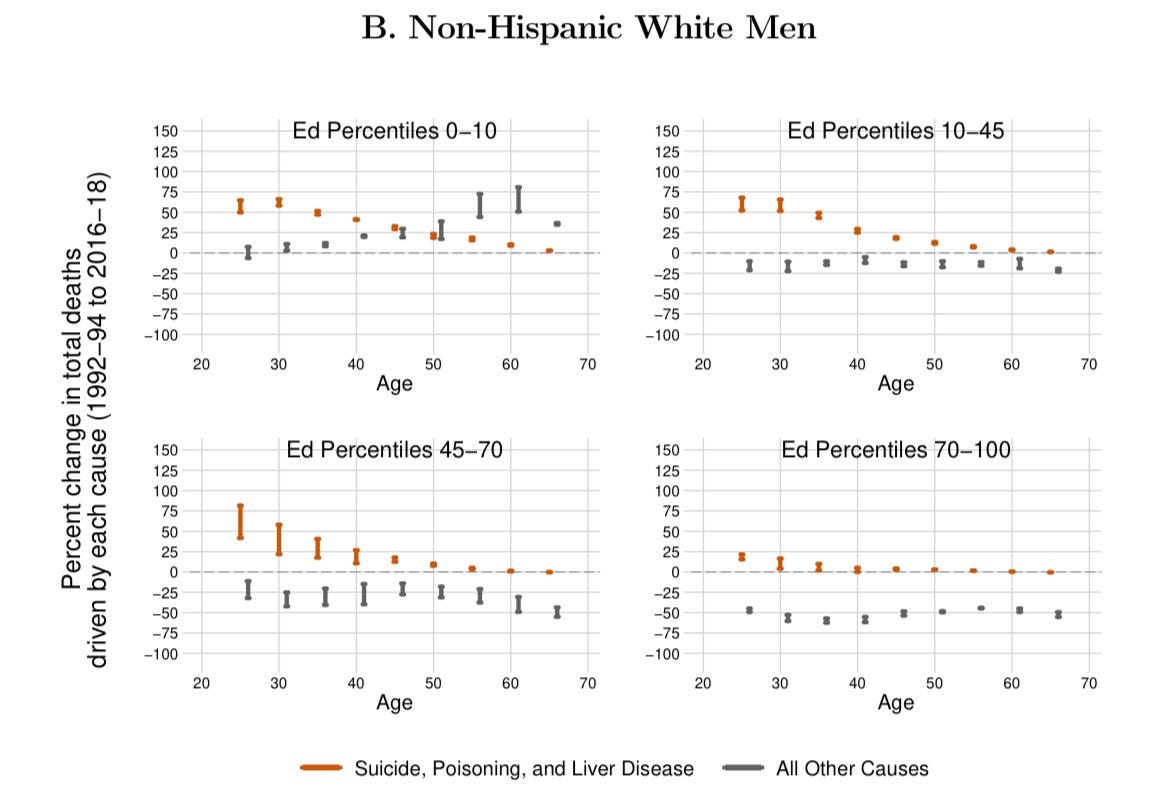

Amid these struggles, Novosad and colleagues documents increases in mortality from suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related disease Among white men in the bottom 10% of education, mortality rose 47-67% between 1992-2018.

What can be done?

Cultural Solutions for Economic Change?

Technological change isn’t destiny. As Rodrik and Stantcheva (2021) argue, innovation’s direction can be actively steered toward creating rather than destroying good jobs. AI could augment teachers’ capabilities and allow nurses to perform more advanced medical tasks. Augmented reality in manufacturing can help humans work alongside robots.

These are promising pathways, especially as aging populations create surging demand for care workers. But we face a cultural barrier: men show reluctance to enter these sectors, comprising only 12% of nurses.

To quote Hoschild’s new book, “Stolen Pride”.

“He turns his nose up at what he thinks of as girly service jobs”.

The challenge is twofold. First, helping boys succeed in education. Finland shows how identities matter: when boys are taught by men, their educational outcomes improve significantly. Yet teaching has become increasingly feminized - in the US, men comprise just 23% of teachers. This creates a vicious cycle, potentially hurting both educational progress and reinforcing gender stereotypes. Breaking this trap requires making teaching more prestigious for men.

Second, as services boom, we need to cultivate interpersonal skills. I would be curious to see more studies on whether male teachers could play a crucial role in developing boys' emotional intelligence.

Media can overcome coordination traps

The barriers to men's entry into care work and teaching are primarily cultural. As argued in my paper “The Decline of the Male Breadwinner and the Persistence of the Female Carer”, there's a crucial difference in visibility. Women's professional achievements happen in public view, gathering broad social support. In contrast, men who undertake care work often do so behind closed doors, allowing outdated stereotypes to persist.

This invisibility creates a classic coordination problem. People naturally seek status and social inclusion within their communities. If men are never celebrated for caring, others may anticipate stigma. Yet this very hesitation perpetuates the negative feedback loop - fewer visible male carers discourages the next potential wave of men from entering these fields. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle that entrenches a straitjacket of masculinity even as economic opportunities shift.

Such concerns are reflected in public opinion - across the political aisle. Pew Survey data shows 56% of US Republicans and 66% of Democrats believe society doesn’t sufficiently value caring men. This bipartisan consensus suggests appetite for change.

Breaking the Macho Gridlock

The past fifty years have shown us two profound technological shifts with contrasting effects:

Medical innovation (the pill) removed a crucial barrier to women’s professional success

Industrial automation eroded demand for brawn.

But while many attribute less-educated men's struggles to automation, we might instead think about culture.

The pill didn’t succeed alone - it worked because Hollywood transformed Western women’s ambitions. Cultural visibility overcame coordination problems. When television began celebrating female lawyers, doctors, and executives, it shifted entire communities' expectations about what was possible and respectable. Prestige bias encouraged wider emulation.

Yet, gender liberation has been noticeably asymmetric. Today, the straitjacket of masculinity creates a coordination problem where men hesitate to enter care and teaching, fearing loss of status. Yet - as our population ages - economic opportunities in care work are rapidly expanding. Cultural rigidities prevent men from seizing new jobs.

Of course, humans aren't infinitely malleable. Despite decades of concerted campaigns, women still show some reluctance to enter STEM. We are not blank slates, waiting to be programmed. But, as we can see from the global heterogeneity of gender norms and recent social change, there is always wiggle room.

So, why aren't we harnessing one of humanity’s greatest inventions - creative storytelling - to overcome these barriers? Television could celebrate male nurses and teachers for their smarts, strength, and success with the ladies. After all, prestige bias works through admiration.

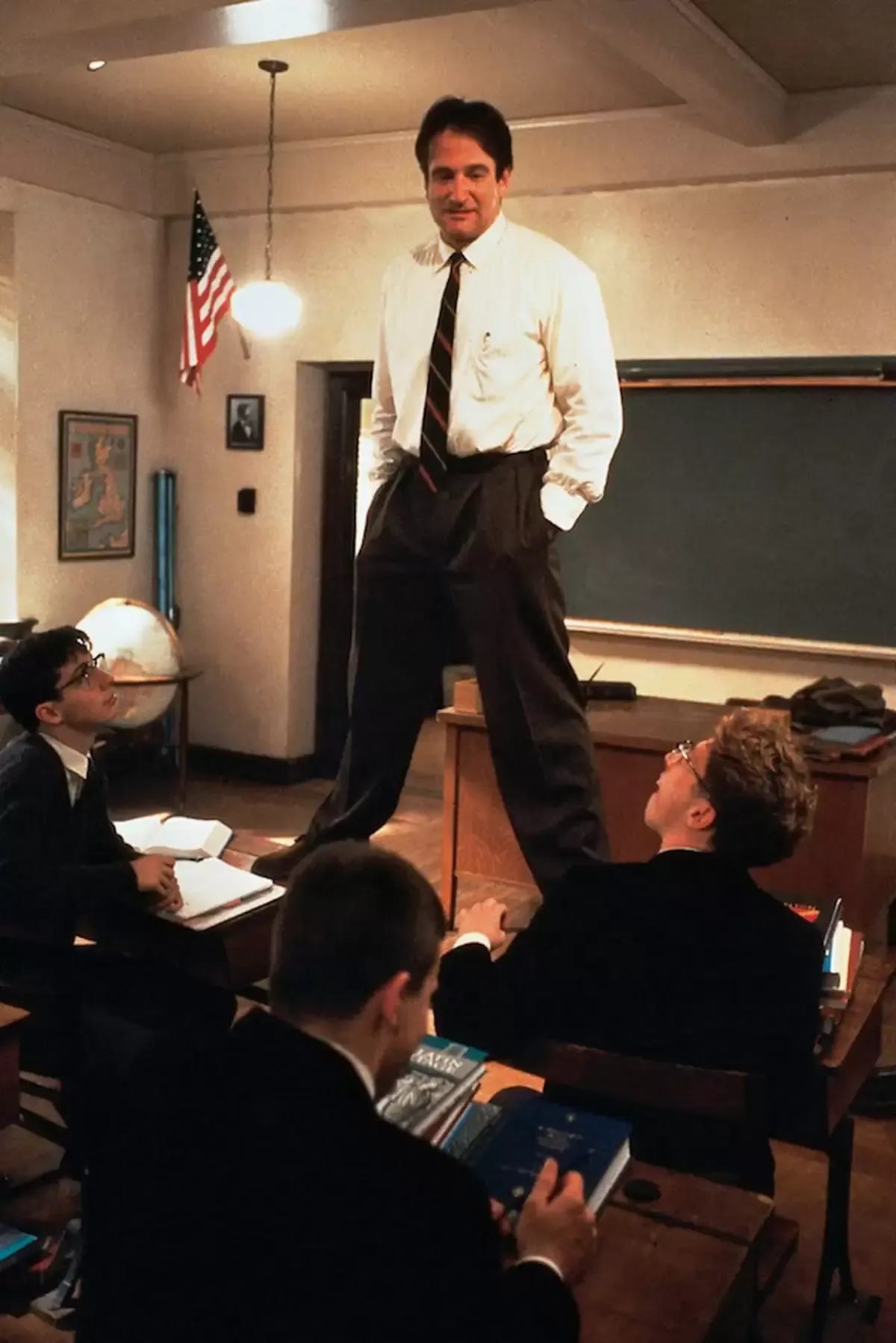

I am afraid that teaching and nursing aren’t exactly prestige occupations. Actually, when it comes to teaching, at least above a certain level, it used to be a predominantly male occupation (as the image drawn from the Dead Poets’ Society movie, ca 1950, attests). One can add that the feminisation of teaching has gone hand in hand with its loss of prestige. (In my teens I saw myself as a future teacher of ancient languages, the subject in which I excelled. I ended up as senior officer in an international organisation. I should say that I don’t have regrets. Schoolmates that went into teaching usually do.)

I wonder if the rise of short form algorithmic entertainment and the balkanization of the media landscape (sometimes called the death of the monoculture) makes it harder to solve the coordination problem?

For example, Netflix could make an absolutely stellar prestige TV show celebrating a friend group of coal miners in West Virginia who take on new roles in nursing and education, but if it’s only watched by well educated members of the PMC, will it really normalize such transitions?