Working-Class Men's Patriarchal Nostalgia

‘Good jobs’ for high school graduates have dwindled. Manufacturing and other manual-intensive occupations that on average paid substantially higher salaries than services have disappeared. This has undercut men’s ability to provide, bruised their egos, fostered patriarchal nostalgia, and catalysed votes for the far right.

Before discussing these contemporary effects, let me first explain how we got here.

Structural transformation and the rise of the male breadwinner

Before the Industrial Revolution, men and women were economically interdependent, working together in a shared enterprise at home, relying upon each other. Men needed women, to survive. But that changed with the British Industrial Revolution. Real wages increased after 1830. Those wages were monopolised by men. This exacerbated patriarchy.

In “Bread Winner: An Intimate History of the Victorian Economy”, Emma Griffin draws on over 600 autobiographies, by working class British men and women born between 1830 and 1903. These autobiographies reveal that girls wanted paid work. Yet their earnings were so low and the volume of housework so large that their parents didn’t consider it worthwhile. So girls were often saddled with childcare and scrubbing, while their brothers were out, earning their own money, and being valued as financial contributors.

Due to sex discrimination in the labour market, women needed to marry to survive. But that did not guarantee their economic security. Women were dependent on men’s good graces, but men were distinctly unreliable. Rising male wages did not lift all boats. Moreover, they amplified patriarchy, endowing men with pride, status, and authority.

In communities where male-dominated industries were substantially higher paying and enabled them to provide single-handedly as breadwinners, men saw themselves as superior.

A similar process of cultural transformation occurred on the Zambian Copperbelt. This region was historically matrilineal. Grooms performed ‘bride service’ by working on her parents’ fields. Subordinate to her kin, men had to prove themselves worthy. But when the mines opened up, young men gained economic autonomy and social authority. Clad in blue overalls, Copperbelt men provided the lifeblood of the Zambian economy and were revered as breadwinners - at least before the 1970s economic crash.

So where the process of structural transformation elevated men’s relative earnings, they gained status and expected deference. Working-class jobs were no picnic, but from America to Zambia, they gave men pride (see Michèle Lamont’s book, “The Dignity of Working Men”).

This wasn’t just a function of economic bargaining power, but also how local economic geography shaped the cultural construction of masculinity. So in places where there was a premium for heavy manual labour (like coal-mining Appalachia or the Zambian Copperbelt), men as a group were substantially elevated. The fortunes of an entire community rested on men’s broad shoulders, and this was culturally celebrated.

The Demise of ‘Good Jobs’

Automation technologies have spread throughout the industrialised world. Western firms have cut costs by automating routine tasks once performed by middle-skill workers in the middle of the wage distribution. This has caused both wage and employment polarisation. It has hurt workers who perform less complex tasks, while generating a skill premium for those at the top (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2019; Acemoglu and Loebbing 2022).

Global competition has also played a role: undercutting US jobs in manufacturing (as shown by Autor et al 2016) and incentivising cost-cutting automation. Organised labour has become too powerless to resist.

As a result of these mutually reinforcing trends (in automation, global trade and worker power), there has been an increase in income inequality.

Working class men have not only lost ‘good jobs’. They have fallen further behind the rich. This is important. People care not just about their absolute income, but their relative status. No man wants to feel like a ‘loser’, as if he can’t keep up, no matter what he tries.

Over in Italy, 22% of young men are unemployed. 70% still live with their parents. Many are now struggling to get jobs, be independent, attract girlfriends, let alone start a family. Fertility has plummeted, now the lowest in Europe. Life is tough for non-elite men, who expected better.

How has this affected gender?

In places where men have been economically defeated, and suffered a disproportionate share of job losses, several effects have been documented:

Gender gaps in employment have closed

Gender gaps in earnings have reduced

Marriage rates have fallen

Job loss hurts men’s egos

Patriarchal nostalgia

Right-wing parties have gained more votes

Gender gaps in employment have closed

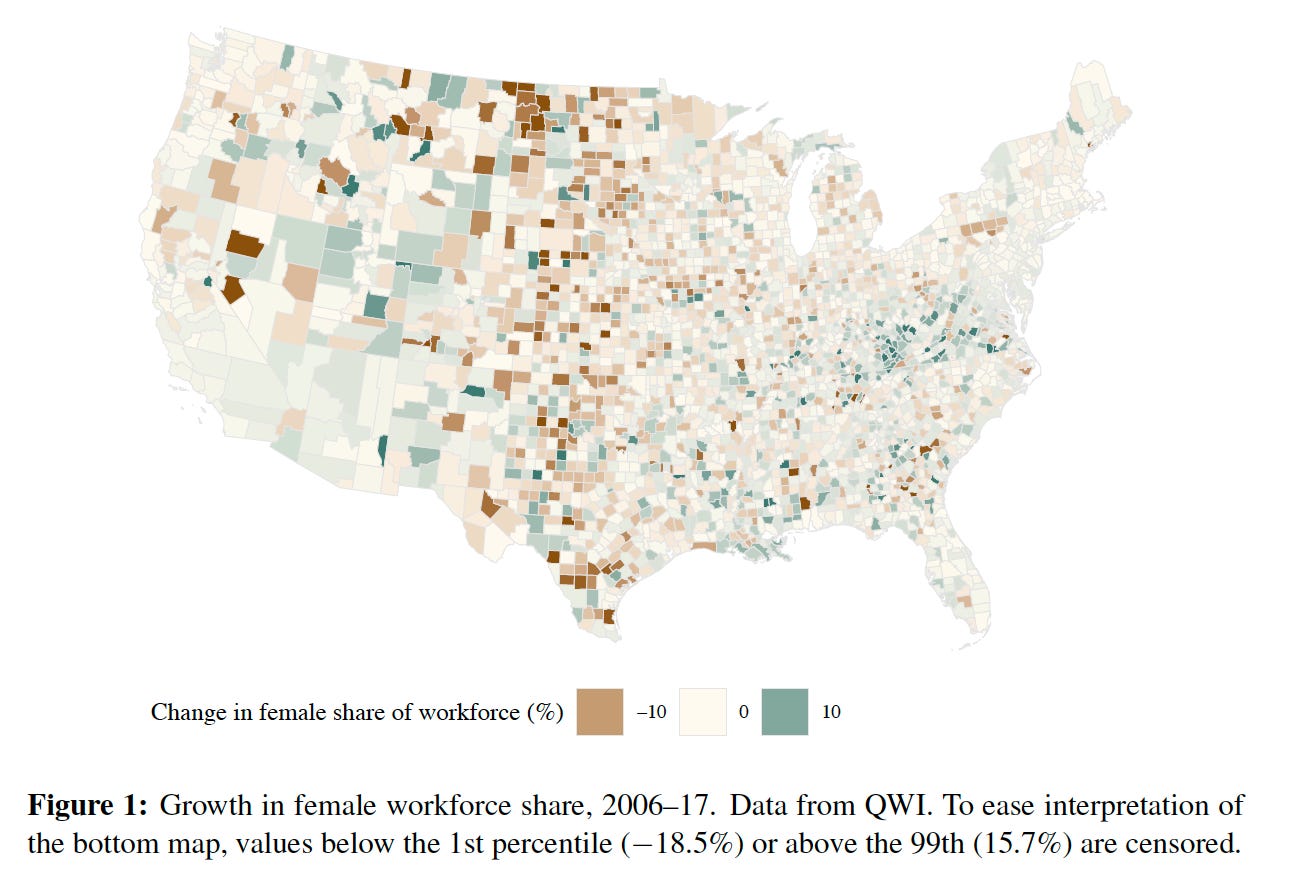

Female employment increased where men’s real wages declined. Across 320 US counties, between 2006-2017, absolute levels of female employment rose while male employment fell. In Appalachia’s coal-mining belt, female share of employment surged. This comes from a new paper by Clark, Khoban and Zucker.

Gender gaps in earnings have reduced

Men who once held blue-collar jobs in mining or manufacturing have suffered a relative decline in earnings. From 1985 to 2018, blue-collar men became less likely to be breadwinners. They also earnt a smaller share of household income. Back in 1985, these men earnt 75% of household income. By 2018, it was 64%.

In American counties where blue-collar work contracted, men’s share of household income fell. These economic shifts appear to have a major social and political effects, which I discuss below.

Marriage rates have fallen

Marriage rates fell alongside the decline in working class men’s relative earnings. When the gender earnings gap closed, men struggled to attract wives.

This is demonstrated empirically by Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2019). It is part of a global trend, discussed in my ‘Unified Theory of Marriage’.

Job loss hurts men’s egos

Men are usually unhappy if their wife earns more - find Kowalewska and Vitali 2023, drawing on a large survey across Europe. Husbands of female breadwinners feel almost as bad as if both of them are unemployed.

Failure to achieve patriarchal ideals makes men feel crap. This toll is larger in countries with stronger norms about male breadwinners (i.e. Germany). Whereas in countries with a long history of full-time female employment, men experience less discomfort.

Likewise in the US, 62% of surveyed men expressed a desire to out-earn their wife - find Clark et al (2023). Most men want to be breadwinners. By contrast, only 45% of women share this preference. Men’s esteem is typically much more contingent on being the breadwinner.

Patriarchal Nostalgia

When men feel like they’re falling behind, unable to realise expectations of pre-eminence, they can react aggressively and endorse hostile sexism. This is a global trend, which I summarise here.

New research in the US and UK points to a slightly different dynamic, which I would call ‘patriarchal nostalgia’ - a desire for how things used to be, back when men were breadwinners. Others term this ‘traditional gender roles’, but that’s misleading since the male breadwinner only emerged relatively recently.

Clark et al (2023) trace American men’s proclivity to say that a man should work while women should stay at home - between 1982, 1987 and 2004. They find that men’s reaction to their wives’ increased earnings is mediated by own employment history. Loss in relative economic status only seems to trigger patriarchal nostalgia among men who have worked in blue-collar work for over ten years.

By contrast, men with no history of blue-collar work who then see their spouse’s relative earnings increase are actually less likely to endorse patriarchal nostalgia.

‘A 25-point increase in a spouse’s relative income for a man with ten years of blue-collar experience in mining or manufacturing corresponds to a seven-point increase in the likelihood of supporting these traditional gender roles’ (Clark et al 2023)

My speculative explanation is that in coal-mining communities like Appalachia where men’s work was once revered as fundamental, but those overalls now lay in tatters, there is a heavier hit.

Likewise in the UK, people who are born into areas with high unemployment are now more likely to say ‘“Husband should earn, wife stay at home” (McNeil et al 2023). I interpret this not as ‘backlash’, but as men’s yearning for relative status.

Republicans have gained more votes

In US counties with more male (than female) layoffs, more people voted Republican. A 25% increase in the number of male layoffs is associated with a 3 point swing to the Right. Female layoffs do not have this consequence.

Moreover when the gender gap in workforce participation closed, more people voted Republican. Clark et al find that a one standard deviation shift towards women’s share of employment (equivalent to 14% of initial workforce size) between 2004–15 drove a 7-9 percentage point swing towards Republicans.

Nationally representative survey data on individual vote choice between 2006-2020 affirms this trend. In counties with more male layoffs, Republicans win.

Republican vote share is also correlated with endorsement of patriarchal nostalgia, that’s what it means to ‘Make America Great Again’.

This is consistent with new research in Brazil. Bolsonaro got more votes in places where unemployment shocks predominantly hit men (Barros and Silva 2023)

What’s the story?

The Industrial Revolution radically transformed gender roles, by increasing family dependence on a single male breadwinner. This elevated men’s status and expectations of deference.

Patriarchal ideologies persist. Despite rising female educational attainment, men are still more likely to be called ‘intelligent’. Analysing a 200 million word corpus US print media, Boutyline, Arseniev-Koehler, and Cornell (2023) find that the term ‘genius’ is still reserved for men.

Elite men continue to realise these patriarchal ideals. America’s male-dominated corporate and tech elite earn some the highest salaries in the world and are widely revered as geniuses. Their status is secure.

Meanwhile, structural shifts in global competition, automation, loss of worker power and rising economic inequality have undercut working-class men’s ability to provide as breadwinners. As a result, many harken for what I call ‘patriarchal nostalgia’.

Great article. I worked quite a bit on the research around China joining the WTO ("China shock"). The societal impacts of these concepts of who should be breadwinner (based on gender) had some even deeper effects. Areas affected by manufacturing jobs moving to China, saw men have higher rates of depression and suicide (some of the suicide rate today can probably still be explained by this).

These perceptions of "gender roles" have very real impacts. I've always thought that this would be much more interesting to teach in intro to economics courses, and what economics can show us.

Fathers as providers has deep evolutionary roots in Homo sapiens. I have done a post on this, prompted by this post. https://www.lorenzofromoz.net/p/breadwinners-homemakers-and-the-decline