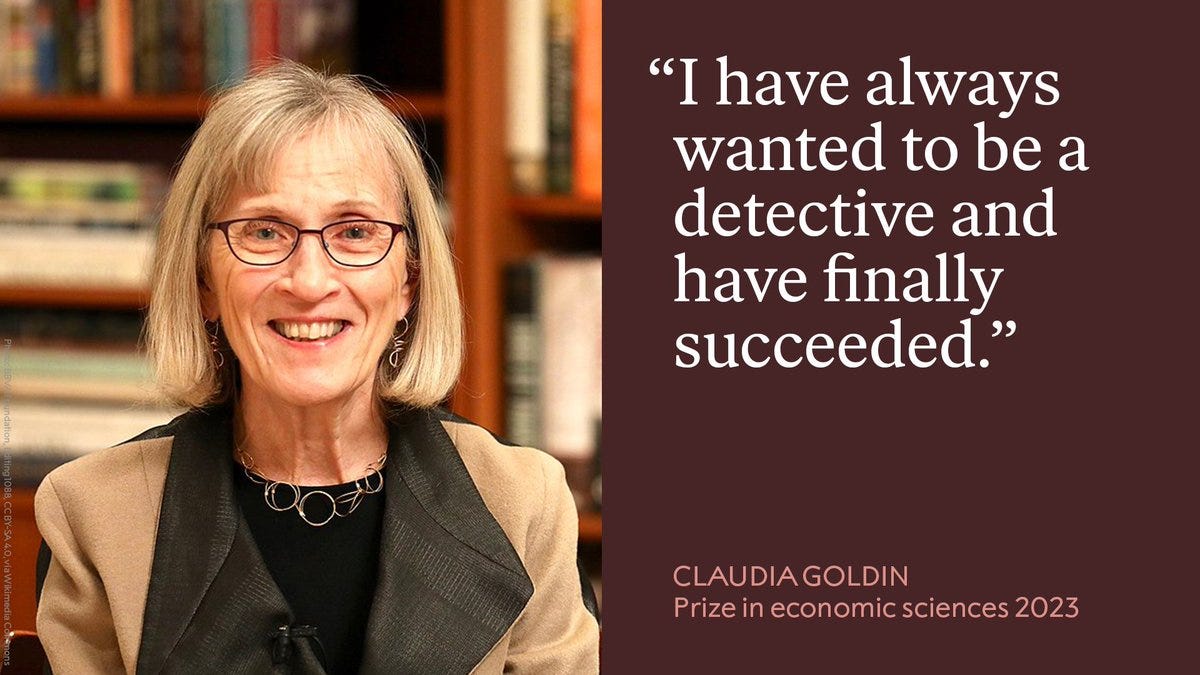

Claudia Goldin: Nobel

Patriarchy has persisted for over ten thousand years. But 20th century skill-biased technological change heralded radical disruption. Women increasingly controlled their fertility, achieved degrees, secured equal rights, raised families and pursued careers. North America’s gender inequalities have been radically reduced. One obstacle remains, however. High-paying jobs are extremely greedy, demanding long hours. Mothers thus tend to pursue jobs with greater flexibility, often paying less. Greater gender equality thus depends on high-paying work becoming more flexible. All this has been amply demonstrated by one pioneering economist: Claudia Goldin.

In this Substack, I discuss some of her major works:

The Power of the Pill

Marriage Bars

The Quiet Revolution

The U-Shaped Female Labour Force Function in Economic Development

Career and Family

Why Women Won (published this morning!)

The Power of the Pill

Before contraception, women's lives were relentlessly interrupted. 60% of their prime age years were spent either pregnant or nursing. Opportunities to gain skills and social networks (beyond other similarly marginalised women) were severely restricted.

Oral contraceptives allowed women to complete college, delay marriage and pursue careers. Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz demonstrate this empirically, for the US.

Marriage Bars

In the early 20th century, US firms and school boards imposed ‘marriage bars’: wedding bells got you fired! Today, it’s unthinkable. Why did it change?

Goldin shows that growing demand created labour shortages. Employment discrimination was thus revoked.

The U-Shaped Female Labour Force Function in Economic Development

Drawing on data for over a hundred countries, Goldin suggests there is a U-shaped relationship between economic development and female employment. As economies transitioned from agriculture to industry, female employment fell. It rose with services-led growth, since these jobs are highly respectable.

Why did female employment fall?

Goldin explains:

“The social stigma against wives working in paid manual labor outside the home is apparently widespread and strong. It almost always attaches to the work of women in male-intensive industries (e.g., mining, iron and steel), but also exists in female-intensive (e.g., clothing, textiles) arid mixed industries (e.g.. food processing).

The stigma is a simple message. Only a husband who is lazy, indolent, and entirely negligent of his family would allow his wife to do such labor…

When women are educated, particularly at the secondary level, they enter white-collar work, against which no social stigma exists”.

Social norms are increasingly gaining recognition among economists. Claudia Goldin has been highlighting shame and stigma for over three decades!!

In our podcast, I asked about East Asia. Goldin explained that the relationship between structural transformation and female employment is not ahistorical, but mediated by advances in technology:

“Historically, the early manufacturing was a real drudgery and dirty and long hours and hot and sweaty and exclude women for lots of reasons. Whereas in development [today], manufacturing often involves electrical appliances and it's not as hot with long hours (although it's often long hours), and it doesn't exclude women to the same degree”.

The Quiet Revolution

In her Ely Lecture, Goldin demonstrated how norms change. From the 1970s, women became less inclined to see work as a temporary posting before marriage and motherhood. With this shift in aspirations, women increasingly chose to control their fertility, delay motherhood, and capitalise on growing demand for skill-based jobs. Like men, they wanted professional careers.

Career and Family

In “Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity”, Goldin identifies a major barrier to gender equality. High-paying professions are extremely ‘greedy’. Clients are demanding, hours are long, and employees must be available around the clock. This is difficult to juggle with child care. Mothers thus tend to pursue work with greater flexibility, which usually pays less.

Greater gender parity is thus contingent on high-paying work becoming flexible. Pharmacy has become ‘a most egalitarian profession’. Commercial, organizational and technological shifts mean that any CVS pharmacist can access the client's records and substitute for each other. This has closed pharmacy’s gender pay gap.

But Goldin adds, labour markets are always mediated by shifts in technology and aspirations. After COVID-induced lockdowns, employees developed a taste for remote work. Tentatively, Goldin suggested this might facilitate more engaged fatherhood. Subsequent research shows she was right.

Why Women Won

Inequalities persist if they are widely accepted and taken for granted. No one is born with a feminist consciousness, nor do we necessarily see structural unfairness. Even if male-dominated institutions are systematically biased, this may go unnoticed.

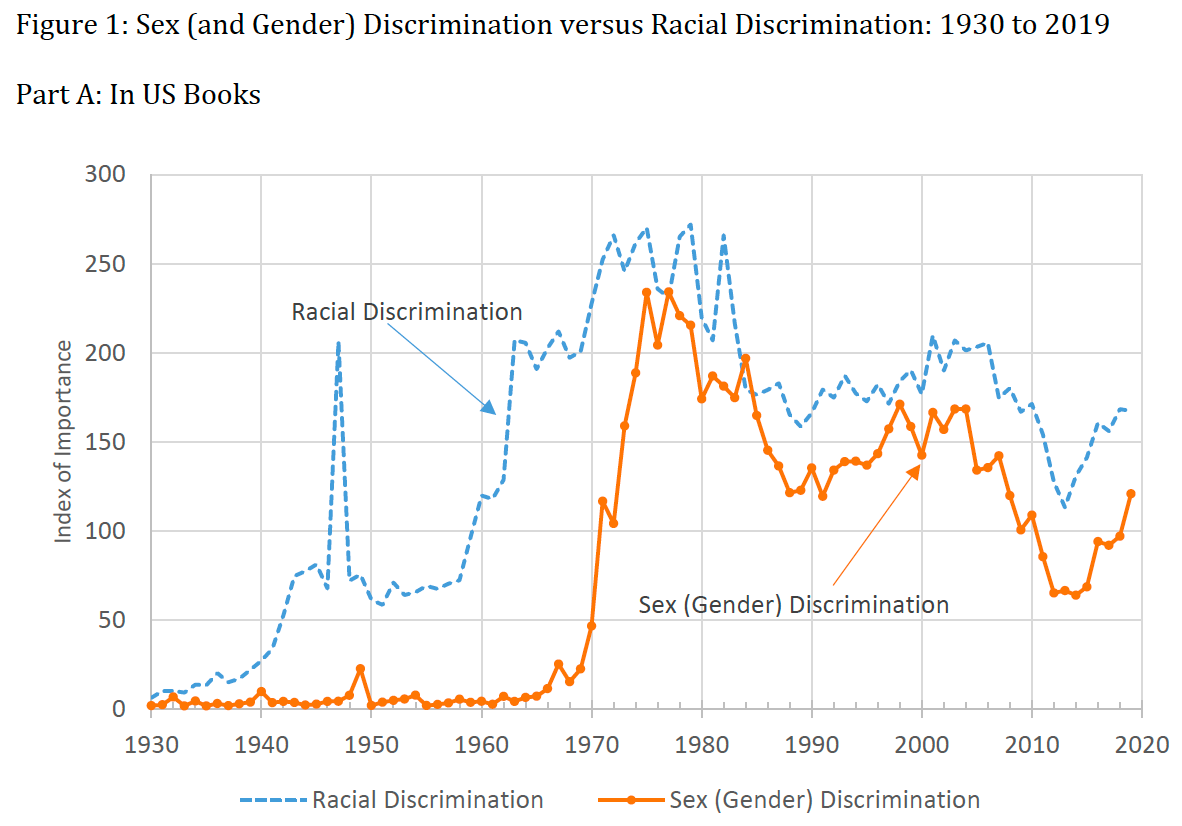

Before the 1970s, US books and newspapers rarely used the word ‘discrimination’ to refer to the treatment of women in the labour market or elsewhere.

Until relatively recently, it was perfectly acceptable for US states to exempt women from jury duty. In 1957, Gwendolyn Hoyt bludgeoned her adulterous husband with a baseball bat. She was swiftly convicted of murder. Hoyt appealed to the Supreme Court, protesting that the trial was unfair, since the jury was all-male. Liberal judges were totally dismissive, declaring:

Women were “still regarded as the center of home and family life” and could be excused from jury duty although that was not the case for Blacks. In a 9-0 decision the Court stated that the Fourteenth Amendment was for racial differences and sex differences in jury selection carried no constitutional significance” (Goldin, 2023).

When the Supreme Court ruled that an all male-jury was perfectly constitutional, Claudia was 15. She grew up in a country where discrimination was rife, but not even recognised.

This morning, Goldin published a new NBER Working Paper, examining the drivers of American women’s rights. She chronicles important legislation regarding gender equality in the workplace, economic/ social spheres, politics, and bodily autonomy. As you can see, it all kicked off in the 1970s.

What led to this surge of feminist consciousness and mass mobilisation for women’s rights?

Goldin suggests 4 core drivers:

Workplace discrimination was rampant. Women were joining a grossly unfair labour market, and got really fed up. [Check out the show “Good Girls Revolt”].

The civil rights movement encouraged a new mentality, recognising structural ‘oppression’. When Black Americans got more rights, white men increased their preferences for white women’s rights (as shown in Figure 13 below);

Civil rights and anti-war protests also endowed women with organising skills;

Feminist activists, like Betty Friedan, highlighted women’s frustrations.

Is she correct?

Well, it is not my place to question a Nobel!

But let me point to Goldin and Katz (2002), Goldin (2006), and Goldin (2021).

Women increasingly sought long-term careers in the public sphere

In the early to mid 20th century, women expected to work briefly, marry male breadwinners, then dedicate their lives to raising children. The white picket fence was culturally celebrated, while bluestocking spinsters were stigmatised. Besides, once saddled with kids and lacking qualifications, there was little alternative. So why mobilise for better treatment in workplaces that were merely temporary?

Thanks to oral contraceptives, skill-biased technological change, and rising labour market demand, women increasingly aspired for professional careers. This longer-term perspective encouraged greater investments in their own human capital.

I suggest that Goldin’s theory of a Quiet Revolution was equally important for feminist activism: women mobilised for equal rights in the public sphere because that is precisely the place where they wanted to be.

University culture and the spirit of ‘68

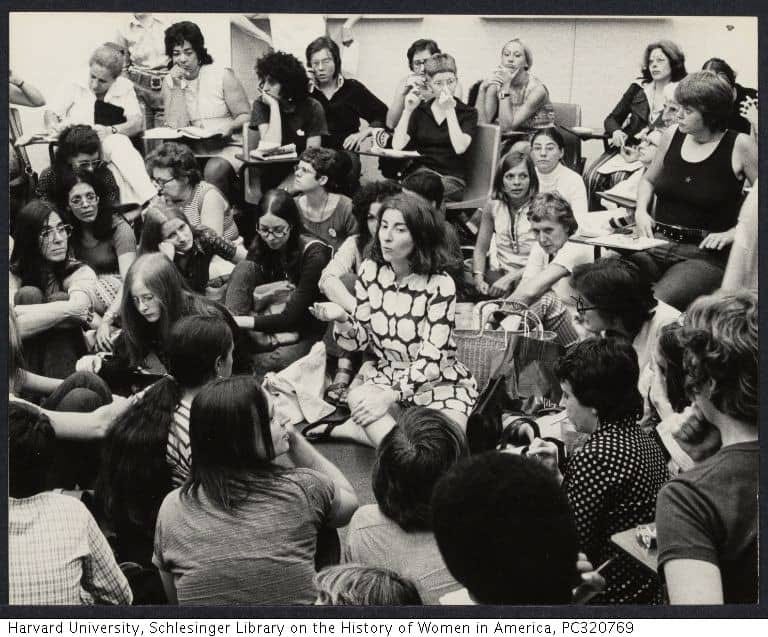

Goldin (2023) argues that the civil rights movement spurred a new way of thinking, about structural ‘oppression’. Let me add a footnote: this was especially true of university campuses, where women redeployed new ideas of injustice.

Oral contraceptives and careerist aspirations didn’t just enable women to complete college courses (fun as they are). Universities are also important spaces for young people to build independent social networks, collectively deliberate and share ideas. This was especially true of the 1960s, when campuses were alive with Counter-Culture. Protests erupted against the Vietnam War; while Rock and Roll music celebrated a spirit of rebellion; and students got loose on recreational drugs.

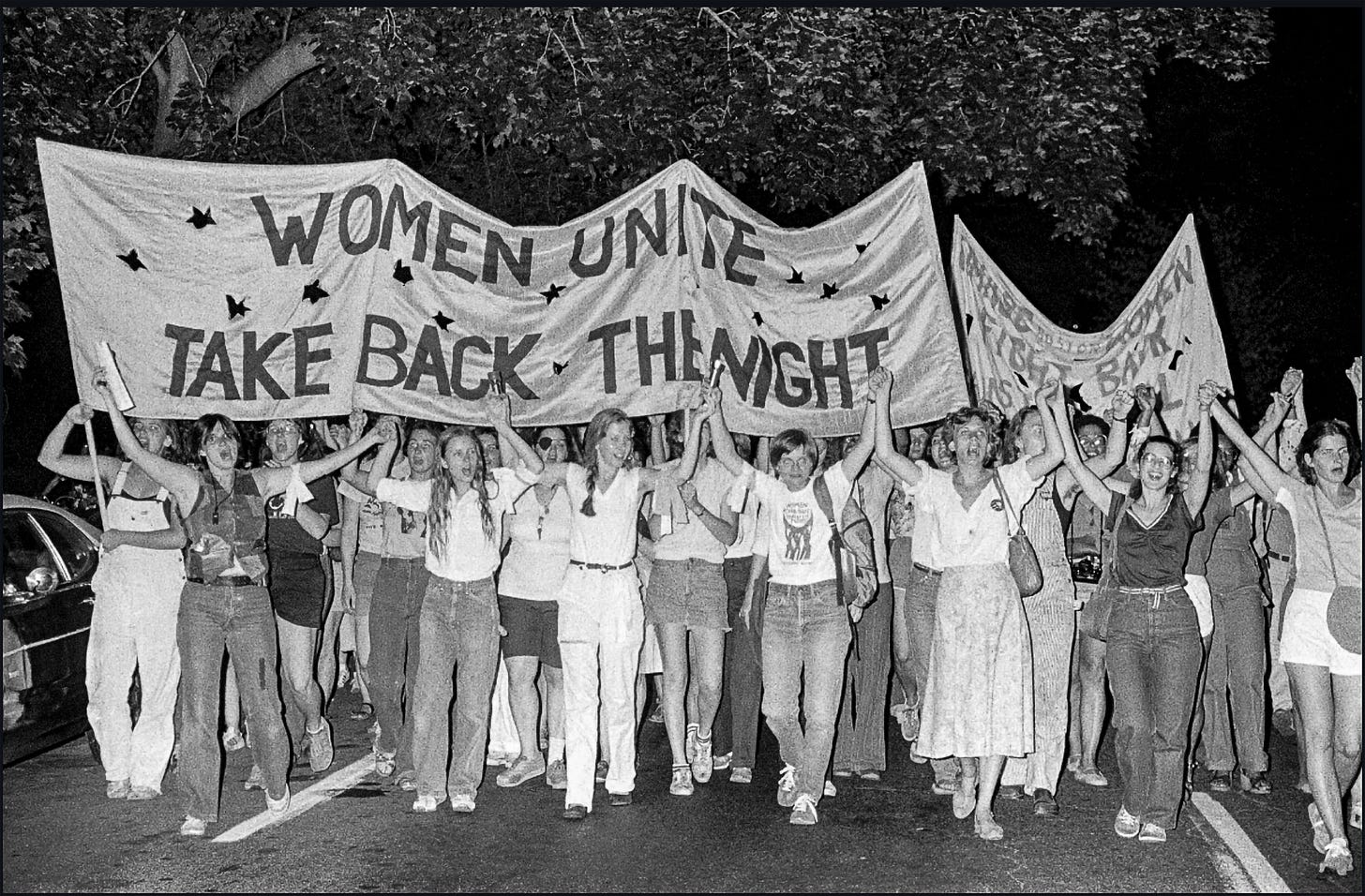

Female undergraduates befriended other women who were independent, childfree, ambitious, frustrated and angry. By sharing their personal battles, women increasingly realised that sexism was systematic. Gathering together in feminist consciousness groups, women reaffirmed their righteous resistance and demonstrated sisterhood. This process was fundamentally collective.

Synchronous group activities (like marches) are also important psychologically, they facilitate group-bonding. Friendships are the foundations of feminist fights against structural discrimination.

Optimism in the power of protest was also fundamental for massive mobilisation. The Civil Rights movement didn’t just introduce new lexicon, it also sowed belief in collective efficacy. Students genuinely believed they could change the world.

When asked whether they favoured efforts to strengthen women’s status, “the college educated were most enthusiastic” - to quote Goldin (2023).

Building on Goldin’s monumental contributions, I thus add 2 minor footnotes:

Women increasingly aspired for long-term careers, so invested in making the public sphere more equal.

Universities (alive with the spirit of ‘68) created spaces for sorority, in which female friends articulated the problem with no name and encouraged each other.

Okay, now back to Goldin (2023).

Thanks to the surge in feminist consciousness, women increasingly mobilised en masse and pressured legislators.

“The impact of the women’s movement in the halls of Congress and within the executive branch until the middle to the end of the 1970s cannot be understated. Almost every major women’s rights bill passed overwhelmingly” (Goldin 2023)

Feminists also got lucky. Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act fortuitously included the word ‘sex’. The National Organisation for Women and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission leveraged Title VII to press charges ‘on account of sex’.

Being Goldin, she obviously shows this empirically:

That is the story of “Why Women Won”.

Claudia Goldin has now done it all. With empirical rigor, she has theorised every major change in American women’s lives over the twentieth century. These dynamics are not necessarily true worldwide, but Goldin has provided the foundations.

“All of Western philosophy is a footnote to Plato,” claimed Alfred North Whitehead. Economics is equally indebted to Claudia Goldin. Contemporary research builds on her theoretical breakthroughs about economic development, technology, families, stigma, and aspirations. Three cheers for Claudia Goldin: Nobel.

Well done. Thanks for this accessible review/summary.

It’s not a Nobel Prize. It’s a fraud cooked by Swedish bankers in the Sixties to elevate the status of neoliberal economists.